Introduction

In 2019, the EAT-Lancet Commission published a comprehensive scientific review that examined global dietary patterns from both health and climate (sustainability) perspectives (Willett et al., 2019). The review recommended a shift toward a sustainable diet characterized by increased consumption of whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes, alongside a reduction in the intake of foods such as meat and dairy products. However, findings from the most recent national dietary survey indicate a gap between these recommendations and the prevailing dietary habits among children and adolescents in Sweden. Specifically, their intake of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and fish remains insufficient, while their intake of red and/or processed meat, salt, and sugar exceeds recommended levels (Moraeus et al., 2018). Recent research shows that the development of sustainable eating habits, aligned with nutritional recommendations that promote public health, can be effectively supported through well-designed and contextually relevant food education (Bjørkjaer et al., 2023). Thus, we believe that renewing food education and facilitating greater cooperation among school staff can help address these problems in Sweden and globally. Food education is often understood as a multidisciplinary concept that integrates health, sustainability, and social and cultural dimensions (Kauppinen & Palojoki, 2023; Smith et al., 2022). In this study, food education is defined as the teaching and learning of food-related knowledge and skills that promote students’ sustainable food choices in relation to health and environmental considerations.

The importance of providing food education to students in early primary school has been underscored by the United Nations World Food Program (WFP), as presented at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Dubai, December 2023 (WFP, 2023). The WFP white paper advocates for a whole-school approach to food education in primary schools, emphasizing its importance because our eating patterns are largely established during childhood (WFP, 2023). This aligns with earlier findings by De Cosmi et al. (2017), Dudley et al. (2015), and the World Health Organization (WHO, 2006). A range of factors – such as parents today having fewer opportunities to prepare meals (Ensaff et al., 2015; WHO, 2006) and varying levels of food literacy among young people (Groufh-Jacobsen et al., 2023) – highlight the necessity of promoting health-conscious and environmentally sustainable food choices. Since food education within households differs, schools play a crucial role in advancing health equity (Public Health Agency of Sweden, 2020; Pulimeno et al., 2020; WHO, 2006) and promoting efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (United Nations, 2015). This can be achieved by equipping students with food-related knowledge and skills through subject-integrated educational activities.

Ballam (2021, p. 413) argues that food education should be emphasized from the primary school level to ensure “consistency and progression in experience, skills, and knowledge” related to food learning. In Sweden, food education has traditionally been part of secondary school education (grades 6-9; students aged 12-15 years) through the school subject known as home and consumer studies (HCS). Although the knowledge content of the HCS curriculum has expanded over the years, particularly in relation to sustainable development (Gisslevik et al., 2016; Oljans et al., 2018), it remains the subject with the fewest allocated teaching hours in the Swedish primary school system. Consequently, HCS has primarily focused on children from grade six onwards, a stage where students’ food preferences are relatively well established. Thus, there is an untapped potential for subject-integrated food education at an early stage in primary school, and we argue that subject-integrated food education in primary schools could benefit and complement the already established HCS subject in Swedish primary schools.

Literature Review

This study adopts a sociocultural perspective on learning and development, viewing these processes as inherently social, mediated, creative, and situated (Strandberg, 2017), as active and experience-based (Smidt & Lindelöf, 2010), and as contextual (Säljö, 2022). The sociocultural perspective supports the development of food-related knowledge and skills among both teachers and students. Learning is understood as a socially mediated process facilitated by more capable peers and cultural tools, or educational tools, such as language and images (Strandberg, 2017; Säljö, 2014; Vygotsky, 1978). As Vygotsky (1978, p. 87) states, “What a child can do with assistance today, she will be able to do by herself tomorrow.” Through the process of internalizing knowledge, learners can advance cognitively and become, as Vygotsky (1978, p.102) describes, “a head taller” within their zone of proximal development. Vygotsky (1978) explained the zone of proximal development in the following manner: “…the distance between the actual development level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” (p. 86).

Following the sociocultural tradition of using tools to mediate learning and development (Säljö, 2014; Vygotsky, 1978), this study utilizes food as a pedagogical tool within subject-integrated food education. Research in food education has shown that food possesses unique attributes when used as a pedagogical tool. For example, its tangibility facilitates learning and understanding (Hård et al., 2024; Stapleton, 2022), and it supports sensory-based food education, thereby broadening students’ preferences (Reverdy et al., 2010; Kähkönen et al., 2018). Using food in this way can also increase student engagement by drawing on their familiarity with it (Hård et al., 2024; Höijer et al., 2011), which in turn enhances their motivation to learn (Haapaniemi et al., 2022). Using food in this way can also increase student engagement by drawing on their familiarity with it (Hård et al., 2024; Höijer et al., 2011), which, in turn, enhances their motivation to learn (Haapaniemi et al., 2022). Using food in this way can also increase student engagement by drawing on their familiarity with it (Hård et al., 2024; Höijer et al., 2011), which, in turn, enhances their motivation to learn (Haapaniemi et al., 2022). In addition, recent studies have explored the value of experience-based learning processes in food education, highlighting their potential to create meaningful and engaging learning opportunities (Beinert et al., 2020; Berg et al., 2023; Bohm, 2022; Hård et al., 2024).

Furthermore, a sociocultural perspective on food education emphasizes the need for creativity and playfulness in learning and development (Strandberg, 2017; Vygotsky & Lindsten, 1995). Recent research has explored playful food-tasting activities that challenge students’ food preferences and promote sustainable food choices (Foinant et al., 2021; Gelinder et al., 2020; Hård et al., 2024; WFP, 2023). Berg (2024) further highlights the importance of aesthetic experiences – such as beauty, pleasure, and taste – in enriching food education.

Food education aligns well with a whole-school approach to food education (WFP, 2023) and is well suited for integration across school subjects (Haapaniemi et al., 2022) due to its interdisciplinary nature (Haapaniemi et al., 2019; International Federation for Home Economics 2008; Renwick & Bauer Edstrom, 2022). Integrating food education into various subjects can enhance students’ food-related knowledge bases and provide more comprehensive and multifaceted perspectives (Haapaniemi et al., 2022; Lindblom et al., 2020). In addition, school meals can provide valuable educational experiences (Peltola et al., 2020; WFP, 2023). However, the successful integration of food education depends on a school structure that promotes subject integration (Bohm, 2022; Haapaniemi et al., 2019; Lindblom et al., 2020).

To effectively teach food-related knowledge and skills across various subjects in early primary education, teachers must embrace the role of food educators, something not widely practiced (Stapleton, 2022). Strengthening teachers’ food-related competencies can be realized by incorporating food education into teacher training programs (Ask et al., 2020; Ballam, 2021; Hård et al., 2024; Piscopo & Mugliett, 2022; Stapleton, 2022). However, implementing food education in primary schools faces challenges, such as limited teacher capacity and time (Ballam, 2021). To adopt the role of food educators, teachers need a solid understanding of dietary guidelines, media health messages, and food allergies and intolerances (Ask et al., 2020), as well as the ability to effectively engage and motivate young learners (Ballam, 2021). Furthermore, food educators should avoid categorizing foods as strictly “good” or “bad” (Berg et al., 2022; Jensen, 2000) and instead focus on delivering positive food messages (Stock et al., 2016). At the same time, sustainability education involves normative elements that need to be balanced (Bohm, 2023).

In summary, it is crucial to align the formative period of students’ food choices (De Cosmi et al., 2017; Dudley et al., 2015; WFP, 2023; WHO, 2006) with teachers embracing the role of food educators, a role currently underdeveloped (Hård et al., 2024; Stapleton, 2022). Given the complexity of this role, early primary school teachers require support in designing effective food education. To support the development of food education in early primary schools, this study used a co-design approach, integrating food as a pedagogical tool across different subjects, such as art, English, and mathematics. To address the limited experience with subject-integrated food education in early primary schools, this study aimed to identify significant elements in a co-design process of subject-integrated food education involving early primary school teachers. The research question was the following: What elements are considered significant when using food as a pedagogical tool in the co-design of primary school education?

Method

The Co-Design Approach

Related to the sociocultural understanding of learning and development as social and situational, this study adopted a co-design approach to develop subject-integrative food education. The process involved collaboration between researchers and early primary school teachers in a Swedish school, drawing on diverse perspectives to create innovative teaching practices (Strandberg, 2017). Blomkamp (2018) highlights the dynamic nature of co-design, where inter-disciplinary collaboration fosters new perspectives and pedagogical ideas. Rooted in concepts such as human resources and inter-thinking (Taar & Palojoki, 2022), co-design values participants’ experiences and collaboration, and aligns closely with participatory research methods (Dietrich et al., 2016; Roschelle et al., 2006; Trischler, 2019). It also shares characteristics with other similar practice-based research methods, such as action research (Sendra, 2024; Zamenopoulos & Alexiou, 2018) and design-based research (Roschelle et al., 2006). In contrast to action research, which is often initiated by teachers, or design-based research, typically led by researchers, co-design actively engages both researchers and teachers throughout the co-design process.

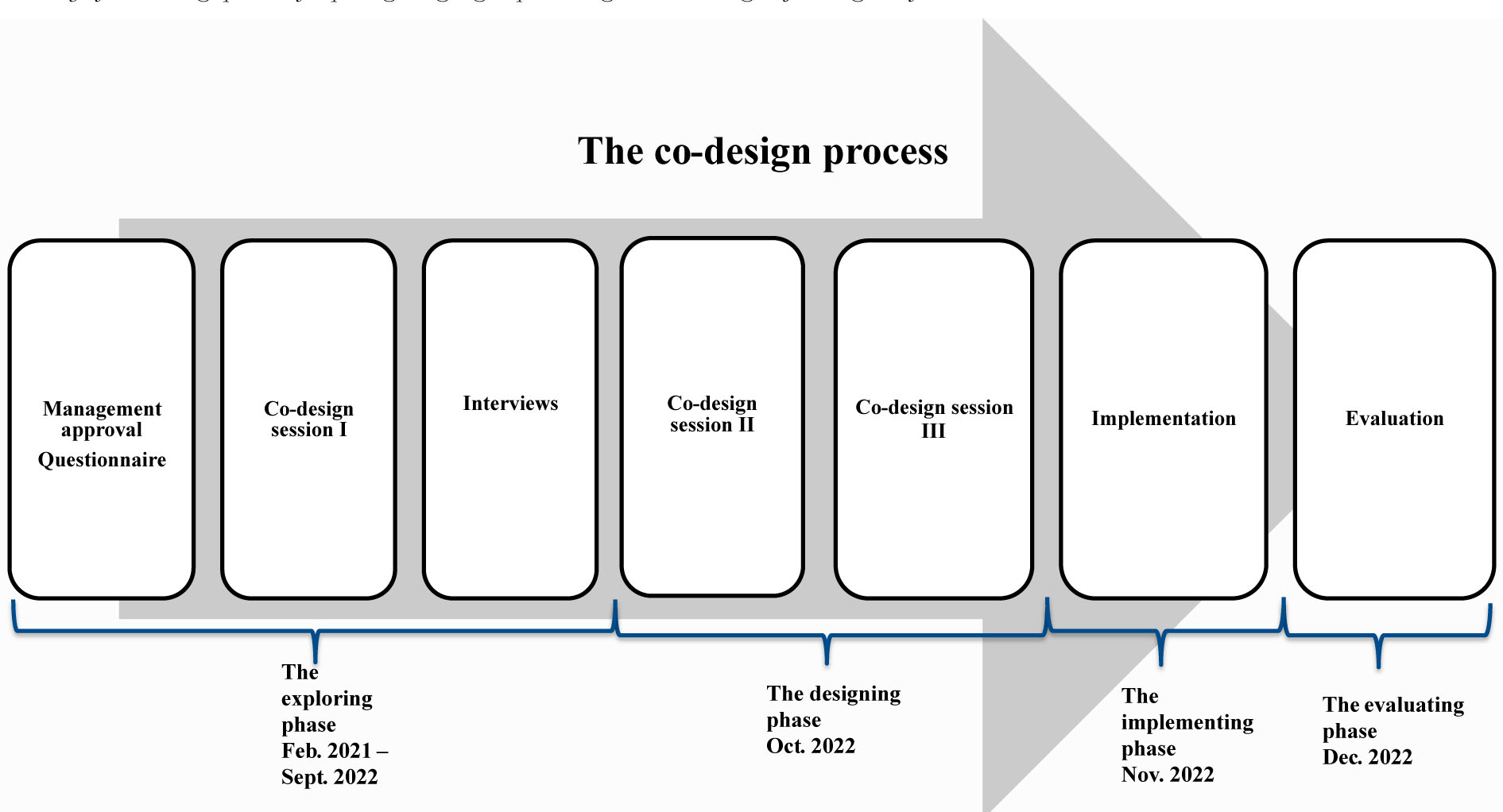

The definition of co-design lacks a universal definition. As Sendra (2024, p. 4) notes, “…there is not a clear definition in policy of what co-design means and what should be expected from a process to be accurately named co-design.” Despite this ambiguity, various frameworks have been proposed to describe the co-design process. For example, Blomkamp (2018) outlines it as a series of exploring, designing, and implementing, while Roschelle et al. (2006) describe it as involving designing, realizing, and evaluating. Moreover, Dietrich et al. (2017) conceptualize co-design as a six-phase process comprising resourcing, planning, recruiting, sensitizing, facilitation, and evaluating. To emphasize the situated and contextual nature of co-design within education, this study adopts a comprehensive four-step process: exploring, designing, implementing, and evaluating. This framework highlights the importance of addressing both the extended preparatory phases (explore, design) and the post-implementing phase (evaluate) in the context of subject-integrated food education. Furthermore, these four steps encapsulate the essential activities of co-design while aligning with other practice-based research methods, such as action research, which follows the cycle of planning, acting, observing, and reflecting (Carr & Kemmis, 1986).

Further, the process of co-design highlights active collaboration, fostering both “collective thinking” (Sendra, 2024) and “collective creativity” (Sanders & Stappers, 2008). Moreover, the presence of a facilitator, represented in this study by the first author, is essential during the design phase to support engagement, communication, mutual understanding, and the envisioning of ideas (Blomkamp, 2018). The facilitator also plays a crucial mediating role in guiding conversations (Zamenopoulos & Alexiou, 2018). In this study, the first author played a crucial role in empowering participants in the co-design process (Dietrich et al., 2017; Mattelmäki & Visser, 2011), serving as a facilitator who used co-design tools, such as providing inspiring materials and implementing structured conversation techniques (Trischler et al., 2019). To ensure the effectiveness of the co-design process, it was essential to establish outcome goals collectively (Roschelle et al., 2006) and to provide an inclusive framework that enabled all participants to contribute democratically to collective thinking (Sendra, 2024).

Research Context and Participants

An exploratory case study approach was employed and regarded as well-suited for the practice-based aim of the study (Yin, 2018). This design allowed a holistic understanding of the complex phenomenon under investigation. Within the framework of the case study, a co-design approach was applied to support early primary school teachers in designing subject-integrated food education. The co-design process followed an abductive approach to knowledge generation, integrating insights from both research theory and school practice (Hurley et al., 2021; Zamenopoulos & Alexiou, 2018).

The case selected for this study was an independent school located in an urban area in southwest Sweden. Although not municipally operated, the school is tuition-free and open to all students through a queuing system. The school has approximately 500 students, ranging from preschool class (6-year-olds) to grade nine (15-year-olds). In accordance with national regulations (Swedish Code of Statutes (SFS), 2010:800), the school provides hot, cost-free school lunches to all students, as well as free school breakfasts. In general, the school emphasizes the importance of sustainable school meals and promotes interdisciplinary learning through thematic instruction.

The case school was selected through contact with school management, who showed interest in promoting sustainable food choices among students and demonstrated an openness to co-designing subject-integrated food education. However, due to changes in the management team during the co-design process, new approvals had to be obtained before recruiting teachers. To initiate collaboration, a meeting was held school staff, during which the first author delivered a research presentation on subject-integrated food education and co-design. The presentation included information regarding sustainable food choices from both nutritional and environmental perspectives, based on nutritional recommendations (Blomhoff et al., 2023). The presentation highlighted the benefit of a whole-school approach to food education and illuminated the potential of food as a pedagogical tool across different subjects. It provided examples of subject-integrated food education aligned with national curriculum guidelines, as well as the co-design process, its theoretical framework, and the ethical considerations inherent in practiced-based research. During the presentation, two teachers with a particular interest in subject-integrated food education expressed their engagement, thereby effectively serving as facilitators for initiating the co-design process.

Subsequently, the initial co-design team was recruited by presenting the project to the teachers, providing them with an open-ended questionnaire comprising of eight questions focusing on food education and sustainability, and following up through email correspondence. The core co-design team consisted of eight teachers from preschool to grade three, representing early primary school (students aged 6-9 years). As the process evolved, additional participants – including teachers and after-school educators – were recruited using a snowballing sampling method, ultimately expanding the team to 14 co-design participants. The participants’ teaching experience ranged from less than one year to 20 years. They represented a diverse range of teaching subjects or areas, such as after-school care, art, mathematics, music, English, home and consumer studies, physical education and health, science, social studies, and Swedish. In practice, however, each teacher taught two to three subjects. All participants were female, except for one. The first author assumed the role of food education facilitator, guiding the co-design of subject-integrated food education. To capture individual experiences and perceptions, members of the core design team were interviewed separately regarding their engagement with subject-integrated food education (Hård et al., 2024).

Data Collection

Data collection commenced with six individual interviews and one pair interview, involving a total of eight teachers. All interviews were audio recorded and subsequently transcribed for analysis. In addition, 10 pages of field notes captured data from the co-design sessions, and a further 35 pages of field notes were generated through participating observations conducted over 3.5 weeks of school days. Finally, the data collection was completed with four pages of field notes from four separate evaluation sessions involving eleven teachers in preschool through grade three.

In alignment with the case study approach, multiple data collection methods – such as interviews, a questionnaire, observation, and field notes – were triangulated throughout the co-design process. Interviews and the questionnaire were used to access the participants’ voices and perspectives. Observations and field notes were regarded as essential for documenting the co-design process, thus contributing an ethnographic element to the study by enabling exploration and representation of the holistic and multifaceted nature of social interaction (Heale & Twycross, 2018). The use of multiple data collection methods aimed to enhance the trustworthiness of the results (Patton, 1999) and to deepen the richness of the data. Triangulation was implemented to enrich the research design by highlighting different aspects of the case (Noble & Heale, 2019).

Ethical guidelines from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority1 were followed and guided the research process, ensuring integrity in the presentation of the findings and the protection of all participants. Informed consent was obtained from teachers and students with additional consent required from guardians of young students (aged 6–9 years). Confidentiality in data storage was maintained, and participants’ identities were safeguarded during dissemination. In accordance with national legislation, no sensitive data were collected. Special attention was given to transparent communication with families and to upholding the integrity of young participants. All participants could withdraw from the research at any time, without providing a reason. However, no participants withdrew from the study; instead, five more were included during the co-design process. As a participating observer, the first author prioritized the students’ need for adult confirmation or assistance over data collection when necessary. Field notes primarily captured food-related verbal expressions, supplemented by contextual and environmental descriptions. Additionally, the first author, acting as facilitator, was responsible for ensuring that the teachers felt comfortable and engaged throughout the co-design process.

Data Analysis

The data analysis aligned with an ethnographic tradition, focusing on the exploration of relationships, influencing factors, and interconnections within the dataset (Reeves et al., 2013). An inductive approach guided the analysis, structured around the chronological co-design phases of the co-design process – exploring, designing, implementing, and evaluating. These phases reflect the conceptual framework underpinning the entire co-design approach, drawing inspiration from Blomkamp (2018) and Roschelle et al. (2006). The data analysis was further guided by the research aim of identifying significant elements within the co-design process of subject-integrated food education in collaboration with early primary school teachers. Additionally, the analysis was informed by the central research question: What elements were considered significant during the co-design process when using food as a pedagogical tool in primary education?

The analysis began by organizing the data material according to the four chronological phases of co-design (Figure 1): exploring, designing, implementing, and evaluating. Thereafter, the dataset was sorted into thematic elements based on similarities. The exploring phase encompassed data related to the recruitment of the case school and participants, while the designing phase included data from the co-design activities and the application of “collective creativity” (Sanders & Stappers, 2008). The implementing phase comprised data from the implemented subject-integrated food education activities. Finally, the evaluating phase focused on capturing the teachers’ voices and perspectives on the co-designed subject-integrated food education. During the reporting of results, the authors iteratively navigated the dataset – revisiting and cross-referencing the material – to ensure the inclusion of information relevant to both the research aim and the guiding research question.

Results

This section is structured based on the significant elements identified within the co-design process of subject-integrated food education. Central to the analysis are the participants’ experiences and reflections, which provide crucial insights into how food education could be pedagogically organized within the context of the case school.

The Exploring Phase

Creating Space for Food Education

The co-design team initially discussed the scheduling of subject-integrated food education. Similarly, the HCS teacher emphasized the importance of proactive teacher planning to facilitate collaborative co-design of subject-integrated food education:

All [teachers] draw up an annual timetable at the beginning of August for the subject-integrated work they wish to work on, and when and how the subjects will be included. If I come and say that now we want to run an interdisciplinary project here across the whole school, it probably wouldn't work because it's full in the schedule; but on the other hand,. . . there wouldn't be any worries. . . having foresight for a long time ahead.

(Frida)

During the interviews, the teachers had two suggestions for the duration of the implemented subject-integrated food education: either an extensive focus over a short period or a less intensive integration over a longer period spread across approximately four weeks and blended with regular education. These suggestions were further elaborated on by two English teachers:

In general, if you work with something for a longer period, it becomes more consolidated, and more students can take in more information and more knowledge. Though we have other things to do as well, this is also important. But I think you should work for a week, intensively, or you could work for four weeks.

(Karolina)

But when you have so many people involved at the same time, it feels like it must be quite an intensive period, one or two weeks. Or you can set a period, a month for example, and we plan something; and then each year group is responsible for doing this over a month.

(Amanda)

However, one mathematics teacher felt that although sufficient time was allocated for the co-design work, it still “added another task to their existing assignments” (Eva, Field note 6).

The Designing Phase

Igniting Inspiration and Fostering Collective Creativity

Although the teachers were skilled in subject integration aligned with the school's profile, they needed specific co-design tools to support food education. To address this need, the first author assumed the role of facilitator, introducing co-design tools to establish the foundation for subject-integrated food education and to foster collective thinking and creativity. These tools included school-based materials and sample lesson tasks in food education, drawn from both food education research and the authors’ practical experience in the field. Examples of design tools presented included a book of food experiments, a board game focusing on spices, and food-related stories featuring literary figures. Furthermore, the facilitator contributed to the creative atmosphere by providing tangible samples of smoothies, tomatoes of various colours, locally-sourced apples, and yogurt bars.

In addition, the facilitator shared food education knowledge and skills by highlighting the importance of taste education and the use of food ranking, as supported by research in home economics education. The facilitator also emphasized the importance of conveying positive rather than normative food messages (Stock et al., 2016) and adhering to the food-based dietary recommendations (Blomhoff et al., 2023). The facilitator role was experienced as challenging, given the dual responsibility for both the collaborative developed subject-integrated food education and the research quality: “I must get the group where I want it. In the last session, the focus was on a good atmosphere and inspiring creativity. Today we must go further” (The facilitator, Field note 4).

Field notes described the facilitator's multifaceted role as encompassing both inspirational and critical evaluation:

The facilitator's role is to coach, inspire, and enable. You represent the research and hold the project together, like the spider in the web. However, it is hard to manage everything, visit everyone, pay attention to everyone, get everyone in a good mood, push, accept, respect, compromise, nag to a certain limit, and set some pressure.

(The facilitator, Field note 4)

You see yourself as a critical reviewer with tips, and you emphasize the importance of having fewer and better learning tasks rather than several. What is the purpose of working with bead tiles? A book about superheroes and food seems good, but how do the students process it? How should the farm visit be followed up?

(The facilitator, Field note 4)

In the preschool class, the Swedish teacher Linda expressed joy during her interview about the collaborative experience of creating something together: “[It will be] something to remember, sit and co-design, and have something from the outside that makes us come [together]; otherwise, we go and talk a little”.

Engaging in Collaborative Thinking to Strengthen and Motivate

While the facilitator's goal was to achieve a co-design process for subject-integrated food education, the co-design team focused on fostering collaboration between teachers and students across grades – a longstanding school objective that had been deprioritized during the COVID-19 pandemic (Field note 2).

The co-design members sought to promote collaboration across grade levels. For example, during an interview, a first-grade teacher expressed that she looked forward to collaborating with all early primary school grades:

I’m excited to have an “integrating project” at the primary school with all involved. We talked about this at school. The goal for this year is to get back to work across the grades, which have fallen a little due to the pandemic. . .. I hope that this can also contribute to that.

(Amanda)

During an interview, a first-grade Swedish teacher further shared her opinion on collective thinking and creativity in the following manner: “I think that when you all sit down and think together, it will flow through much more” (Emma).

Early in the co-design process, Britt, a grade-three art teacher, expressed her enthusiasm for the collaborative work during co-design: “…a seed has been planted in me, fun to sit down and co-design, something fun will come of it later. Otherwise, you mostly talk to your work team and plan with them” (Britt).

In her interview, Frida underscored the potential of involving various school staff members in food education, including after-school care educators and school food service staff, as part of a whole-school approach:

We have an advantage in that we work at a free school, and everyone is under the same core. There is a lot of collaboration with the kitchen and home, and consumer studies, for example, in the making of meatballs.

(Frida)

However, across the different grade levels, teachers held varying expectations regarding the planning details, output of the co-design work, and inter-grade communication. While some appreciated the freedom to design learning tasks within their own grade, others found the independent planning to be challenging. During the co-design evaluation, Britt expressed her frustration as follows: “Communication between the [different teacher] teams did not work. We decided to plan together, but not how to plan. Everyone knows what they are supposed to do, but not what the others are doing” (Britt, Field note 6).

Following the management's recommendation to incorporate school meals into subject-integrated food education, students were encouraged to participate in a “veggie challenge” during Vegetable Week, where they were challenged to try new vegetables every day. In addition, food waste reduction activities were organized in collaboration with the school food service. As part of these efforts, students measured food waste and created posters featuring the slogan: “Food in the stomach, not in the rubbish.”

Addressing Food-Related Questions

The authors proposed three established sustainability challenges related to food education for the co-design team: reducing sugar intake, increasing the consumption of fruits and vegetables, and promoting the exploration of new foods and flavours. Following collaborative discussions, the co-design team identified three focus areas deemed suitable for early primary school students: fruits, vegetables, and reducing food waste.

During the third co-design session, the facilitator noted a discussion about the practice of leaving an empty plate during school meals, highlighting a tension between normative expectations and a more permissive approach to food education. Preschool teachers emphasized the importance of finishing everything on the plate, whereas second-grade teachers focused more on the value of encouraging students to try new foods, regardless of whether they eat everything on their plate. However, most teachers agreed that food waste was more acceptable when students were introduced a new dish, but less so with subsequent servings of the same dish. One teacher expressed concerns regarding the case school's food waste reduction in relation to school meals: “What is our policy? How do we teach about food waste?” (Linda, Field note 4).

The facilitator noticed a shared interest among the teachers, except for the HCS teacher, in strengthening their food education knowledge and skills, which was expressed as “a need for professional development” in both the questionnaire and interviews. For example, during co-design session three, Linda conveyed uncertainty regarding the use of pedagogical food models: “What about the plate model or the food circle? [Swedish pedagogical food models of food groups’ respective food proportions.] Are they still valid?” (Linda, Field note 4).

Although the importance of eating sufficient fibre and whole grains was not specifically addressed in the co-design discussions, the facilitator suggested this topic in a discussion on students baking stick bread: “Could the stick bread be healthier with whole wheat flour?” (Field note 4).

However, several teachers pointed out the importance of ensuring students consume enough energy-rich foods. Broader discussions on student nutritional intake were relatively limited. In contrast, one teacher highlighted the need for variation in food intake in relation to the “food circle” [a pedagogical food model] during her interview:

The Implementing and Evaluating Phases

Navigating the Practical Boundaries Between Creativity and Collaboration

As part of the collective thinking process, learning tasks such as baking stick bread, preparing an outdoor apple dessert, making smoothies, and tasting different fruits and vegetables were discussed. During co-design session II, participants also considered incorporating physical activity and involving additional staff members, such as the home and consumer studies teacher, school food service staff, school nurse, and after-school care educators. However, preschool teacher Linda took on a critical role by questioning aspects of the teaching ideas and project organization by raising the following questions: “Is everything feasible? Will it work with the students’ groups?” (Linda, Field note 3). In contrast, another teacher reasoned further: “You can perhaps evaluate that afterward. You had a high ambition before, and what was the outcome?” (Amanda, Field note 3).

Through creative learning tasks such as tasting fruit and vegetables and discussing sensory experiences, students developed their language skills by verbalizing the flavours they encountered. Moreover, fruit and vegetables functioned well as effective sources of inspiration for poems and drawings. For example, students engaged in visual arts by recreating Andy Warhol's famous banana pop art paintings from 1967. Through a close examination of real bananas, students were encouraged to pay attention to fine details. The process began with outlining the banana on paper, followed by marking its brown spots before highlighting the yellow colour against a brightly coloured background. As they sought to capture the unique character of each banana, students became aware of the individuality of each fruit and the importance of recreating uniqueness. As art teacher Linnéa noted, the students “learned how to see” (Linnéa, Field note 6). Furthermore, through the collaborative activity of planting sandwich cress, students were introduced to forming hypotheses and making observations earlier than is customary in traditional Swedish science studies. Finally, following a mathematics lesson that involved dividing fruits into parts, Eva observed that the students benefitted from having a tangible reference point. Reflecting on the learning processes, a first-grade teacher emphasized the significance of active engagement from both teachers and students: “We make connections, and the children make connections” (Eva, Field note 6).

During the co-design evaluation, the subject-integrated food education was described as “a bit intense but manageable.” However, in the implementation phase, the activities needed to be reduced, resulting in what was referred to as a “slimmed-down project” (Amanda, Field note 6).

Overall, the teachers reported a high level of satisfaction with both the teaching and learning outcomes, as well as the significant integration of subjects in the subject-integrated food education. As Britt concluded: “Food is central in our lives, but it [subject-integrated food education] does not stand as a single work area but more as part of another theme” (Britt, Field note 6).

Discussion

The results identified five significant elements considered important in the co-design process of developing subject-integrated food education: creating space for food education, igniting inspiration and fostering collective creativity, engaging in collaborative thinking to strengthen and motivate, addressing food-related questions, and navigating the practical boundaries between creativity and collaboration. These elements are examined through the lens of sociocultural theory, focusing on the use of social and cultural tools (Säljö, 2014; Smidt & Lindelöf, 2010; Vygotsky, 1978), along with a whole-school approach to food education (WFP, 2023; WHO, 2006).

In line with the concept of cultural tools (Smidt & Lindelöf, 2010; Vygotsky, 1978), participating teachers were supported and empowered to design learning tasks with the help of specific co-design tools (Dietrich et al., 2017; Mattelmäki & Visser, 2011; Tischler et al., 2019). The co-design tools included, for example, access to recent research in food education and inspiring teaching material. They served to familiarize the teachers with the field of food education and actively engage them in developing subject-integrated food education. Overall, teachers expressed a high level of satisfaction with subject-integrated teaching and learning. Their subject-specific knowledge and teaching experience played a crucial role in developing pedagogically effective subject-integrated food education (Strandberg, 2017) within the school case. This emphasized the situated nature of their professional practice. The implemented food education themes - such as fruits, vegetables, and reducing food waste - were not confined to a single school subject but were successfully integrated across several subjects. Integrating food education into teacher education (Gisslevik et al., 2017) would equip teachers with essential knowledge of pedagogical food models and current nutritional recommendations. This, in turn, would enhance the quality of food education in the future. For example, the use of food as a pedagogical tool facilitated learning across various subjects, such as art, mathematics, and language development. Moreover, teachers rediscovered previously used food-related learning activities, such as drawing the school meal using the plate model, incorporating food prices in mathematics lessons, and reading a humorous fictional story in English class about a potato with unhealthy indoor habits.

The importance of clear goal setting has been identified in co-design research (Roschelle et al., 2006). In this study, it functioned as a cultural tool (Säljö, 2014; Smidt & Lindelöf, 2010; Vygotsky, 1978), supporting teachers’ objective of collaborating across student grades. Although the co-design team was generally accustomed to collaborative work and social tools (Säljö, 2014; Smidt & Lindelöf, 2010; Vygotsky, 1978), their preferences varied: certain teachers favoured full collaboration developing subject-integrated food education across grades, while others preferred to cooperate within their own grade level. Although the initial co-design goal was to foster collaboration across grade levels, in practice, the collaboration remained within the existing grade levels. The results underscored the importance of balancing teacher autonomy when developing new teaching methods. Further, it was important for the teachers to “own” the food education initiative, with one teacher expressing that “it is not just one more thing to educate students about” (Eva, Field note 7).

Within the co-design process, the facilitator's role was pivotal in engaging teachers in developing subject-integrated food education, echoing approaches by Blomkamp (2018) and Zamenopoulos and Alexiou (2018). From a sociocultural perspective, the facilitator can be seen as a human tool that mediates learning and collaboration (Säljö, 2014; Vygotsky, 1978). In future practice, the role of a “food educator facilitator” might not need to be limited to an external researcher, rather it could be fulfilled by a school staff member who has relevant knowledge and skills in food education. An additional factor in engaging teachers in food education is the establishment of a supportive school organization (Bohm, 2022; Haapaniemi et al., 2019; Lindblom et al., 2020). Such organizational support enables the allocation of adequate time and space for “collective thinking” (Sendra, 2024) and fosters “collective creativity” (Sanders & Stappers, 2008), both of which are essential for collaborative pedagogical development.

In this study, creativity – viewed from a sociocultural perspective and enhanced by both playfulness and lived experiences – played a central role in the teacher-led development progress. However, not all learning tasks were developed during the co-design sessions; creativity emerged both as a collaborative and individual endeavour, often expressed informally. The evaluation phase revealed a strategic emphasis on fewer, yet higher quality, learning tasks to effectively manage the co-design process (Roschelle et al., 2006). During implementation, the teachers learned to balance introducing the number of new learning tasks and accommodating the daily capacities for both them and their students. Ultimately, some of the discussed learning tasks were discarded (e.g., the outdoor apple dessert), while others were deemed more suitable for certain classes (e.g., colour-based picture activities). A few tasks were modified to better fit classroom dynamics (e.g., having the teacher make a smoothie instead of the students), and new tasks were added (e.g., tasting tropical fruits).

To successfully implement a whole-school approach to food education, as recommended by WFP (2023), our co-design process revealed the importance of foresight in planning (Bohm, 2022). Equally important is maintaining flexibility in terms of time and place, thereby enabling meaningful participation from the school food service, school nurse, and after-school care staff in the co-design of subject-integrated food education. Unfortunately, this co-design process was not efficient enough to fully exploit the educational potential of elements such as school meals. This limitation stemmed primarily form a lack of coordinated planning time and insufficient foresight during the planning process (Bohm, 2022; Haapaniemi et al., 2019; Lindblom et al., 2020). The importance of inclusive and democratic co-design practices to support a whole-school approach to food education has also been underscored by Sendra (2024). In addition, the critical role of active and supportive teacher engagement in fostering efficient collaboration throughout the co-design process has also been highlighted by Haapaniemi et al. (2022) and Lindblom et al. (2020).

In summary, the co-design process, supported by a facilitator, proved to be an effective approach for developing subject-integrated food education. Teachers’ knowledge and skills in food education played a crucial role in developing the content, and their active engagement and prioritization of food education emerged as key factors in its successful integration. In line with a sociocultural perspective, the use of social and cultural tools (Säljö, 2014; Smidt & Lindelöf, 2010; Vygotsky, 1978) as well as situated learning processes (Strandberg, 2017) were central to the co-design approach, as demonstrated in this study. Key elements specifically highlighted in the co-design process included the teacher's knowledge and skills in food education, the use of co-design tools, and the role of a food education facilitator in fostering creativity and collaboration. Through active participation in the design and discussions on subject-integrated food education during the co-design sessions, teachers were provided with opportunities to advance their food education competencies, thus aligning with the concept of the zone of proximal development. By acquiring and internalizing food education knowledge and skills, teachers advanced their professional development, becoming more confident and capable food educators – figuratively growing a head taller (Vygotsky, 1978). Future explorations of subject-integrated food education could benefit from examining co-design approaches in later stages of schooling or through focused teaching and learning perspectives.

Strengths and Limitations

One of the key strengths of this study is its structured co-design approach – encompassing exploring, designing, implementing, and evaluating subject-integrated food education – which provided a clear framework for developing subject-integrated food education. This approach proved successful in introducing food education within the early primary school context. Additionally, the trustworthiness of the data was strengthened by the consistent involvement of the facilitator, participating observer, and first author, thereby enabling rich, in-person data collection throughout the process. However, analysing the co-design process while simultaneously monitoring its progression proved to be a complex task. The facilitator encountered challenges in navigating the dual roles of researcher and facilitator (i.e., research participant), requiring frequent shifts between these roles depending on the specific demands of the study. Ultimately, the facilitator's role was most prominent during the initial co-design phases, particularly in the creative development stages, whereas the researcher role became more significant during subsequent phases, which focused on observing and evaluating the subject-integrated food education.

The co-design process is inherently time-consuming (Roschelle et al., 2006), and this was further extended during the COVID-19 pandemic. Maintaining consistent contact with the case school proved challenging, particularly due to changes in school management during the exploring phase. For the facilitator (the first author), the site-dependent nature of the co-design work was further complicated by uncertain timeframes and difficulties in sustaining teacher engagement and motivation until in-person meetings could be resumed. Fortunately, the case school's existing experience with subject integration – owing to its profile – enabled an effective implementation of the co-design process once initiated. In contrast, schools without a similar profile may require more time to establish collaborative structures and integrate subjects effectively.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the successful development of subject-integrated food education in collaboration with early primary school teachers depended on their knowledge and skills in food education, the recognized value of engaged collaboration, and the support of a dedicated food education facilitator. The teachers felt empowered to engage in collective thinking and collaboration within an area that was unfamiliar to many, while also creating space for the development of subject-integrated food education. Among the key elements identified, collaboration and pedagogical competence in food education were instrumental in facilitating the co-design process. However, a food education facilitator equipped with food education knowledge and skills was essential for igniting creativity, addressing food-related questions, and providing evidenced-based knowledge about food education. Furthermore, our findings emphasize the need for efforts to support students in making sustainable food choices. Such efforts should be embedded as a permanent component of the “school year wheel,” rather than confined to short-term projects focused on food and sustainability. Based on our findings, we propose that subject-integrated food education in the early years be formally included in the national curriculum and incorporated into teacher training programs.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their gratitude to the staff of the case school for generously sharing their time, engagement, and positive atmosphere, and for contributing to the research field of subject-integrated food education.

Notes on Contributors

Louise Hård is a doctoral student in the Department of Food and Nutrition, and Sport Science at the University of Gothenburg. Her doctoral thesis focuses on a co-design process of exploring, designing, implementing, and evaluating subject-integrated food education in early primary school.

Päivi Palojoki is a professor in Home Economics Pedagogy at the University of Helsinki, Finland, and an affiliated professor at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. Her research focuses on subject-didactic questions related to the teaching and learning of Home Economics in basic and teacher education.

Christel Larsson is a professor in Food and Nutrition in the Department of Food and Nutrition, and Sport Science at the University of Gothenburg. One of her research focuses is on how to promote healthy dietary habits among children and adolescents, and food-related learning.