Article History Submitted 29 January 2024. Accepted 8 April 2024. Keywords Court of Justice of the European Union, Citizenship, Citations, Network Analysis, European Social Citizenship |

Abstract In the aftermath of the Dano judgment, the scholarship unanimously identified a jurisprudential shift towards a more restrictive interpretation of European citizenship, leading to the refusal of social assistance. Yet, the extent to which the observed shift in the approach of the Court of Justice of the European Union (the Court) permanently redirected the trajectory of European social citizenship remains understudied. The emphasis placed on contextual causes hints at a possible return to the earlier approach if the political climate becomes more conducive to the development of European social citizenship. This article empirically revisits the Court’s citizenship jurisprudence from a novel perspective, that of citations. The research question seeks to determine if there is a fundamental shift in the reference frame of citizenship judgments and the extent to which the Court’s restrictive approach, observed in the 2010s, persists in recent judgments. All citizenship judgments delivered until October 2023 are examined by combining network and legal analysis. The findings reveal a fundamental and potentially strategic shift in the reference frame of citizenship judgments delivered from 2016 onwards compared to judgments delivered before. Crucially, despite the revival of social Europe in recent years, the Court has not returned to its pre-Dano approach. |

|---|

The citizenship jurisprudence of the Court of Justice of the European Union (the Court) has undergone a well-documented metamorphosis in recent years. The shift is evident as in its early citizenship jurisprudence, the Court often resorted to an expansive interpretation of citizenship provisions to enhance the rights of Union citizens, while in later judgments, it adopted a more restrictive interpretation, emphasising the limits to such rights (NicShuibhne 2015; Spaventa 2017; Minderhoud and Mantu 2017). The shift is particularly evident in cases concerning the entitlement of economically inactive citizens to social assistance. In judgments delivered in the late 1990s and early 2000s the Court largely sided with the individual seeking social assistance. In comparison, in cases with comparable facts delivered in the mid-2010s the Court mostly ruled in favour of Member States seeking to refuse such entitlements.

The Court’s shift towards a more restrictive interpretation of European social citizenship is widely uncontested, yet its nature is empirically understudied. Almost a decade after the first signs emerged, it remains unclear whether the shift extends beyond the regular jurisprudential ebb-and-flow and if it permanently redirected the trajectory of European social citizenship. On the one hand, the shift is interpreted as signalling a “reactionary phase” (Spaventa 2017) and the “swift dismantling” (O’Brien 2017) of European citizenship, accompanied by a return to its market origins (Minderhoud and Mantu 2017; NicShuibhne 2015; Spaventa 2017). On the other hand, given the instrumental role of contextual developments in instigating the Court’s turnaround, as “judges read the morning papers” (Blauberger et al. 2018), it can be deduced that if and when the political climate becomes more conducive to the development of European social citizenship, the Court will return to its earlier approach. Considering the recent legislative impetus stemming from the 2017 European Pillar of Social Rights,2 the “roaring 20s for Social Europe” (Kilpatrick 2023) fostered a political climate which could be perceived as welcoming to the Court’s further development of European social citizenship.

Against that background, this article seeks to empirically determine if there is a fundamental shift in the reference frame of citizenship judgments and the extent to which the Court’s restrictive approach toward European social citizenship, observed in the 2010s, persists in recent judgments.

In approaching the question, the citations found in all judgments delivered by the Court up to and including October 2023 are examined quantitatively and qualitatively. The article contributes to existing literature by revisiting the Court’s entire citizenship jurisprudence through a novel lens, that of citations, and by combining network and legal approaches.

Even though scholars largely agree that there is a shift “from the rights-opening to the rights-closing approach” (Šadl and Sankari 2017, 91), there is a lack of consensus as to the turning point of this jurisprudential shift. Šadl and Sankari identify the first signs of the shift in 2011 (Šadl and Sankari 2017), with the delivery of Ziolkowski and Szeja,3 while for Dougan the seeds were planted as early as 2008 (Dougan 2013), with Förster4 and Vatsouras.5 Most accounts converge on the fact that Brey,6 Dano,7 Alimanovic,8 and García-Nieto9 were instrumental in solidifying the Court’s shift (Jesse and Carter 2020; Blauberger et al. 2018; Šadl and Sankari 2017; Schmidt 2017; Minderhoud and Mantu 2017). Considering this, the analysis will focus on these four judgments which are undisputedly perceived as important milestones in the Court’s turnaround. On the other hand, the so-called “citizenship classics” (Šadl and Sankari 2017) encompasses the Court’s earlier case-law which put “flesh on the bones” (O’Leary 1999) of European citizenship through the interpretation of the Treaties (Menéndez, 2010). The term frequently appears in scholarly accounts and is associated with an expansive interpretation of European citizenship and pro-individual outcomes (Shaw 2010; Šadl and Sankari 2017; Šadl and Madsen 2016). The present enquiry uses the list compiled by Šadl and Sankari consisting of Martínez Sala,10 Grzelczyk,11 D’Hoop,12 Baumbast,13 and Bidar14 as a departure point (Šadl and Sankari 2017). The analysis of citations can reveal whether cases regarded as turning points in this jurisprudential shift replaced the Court’s classic citizenship jurisprudence as dominant points of reference.

The article is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the theoretical framework while the research design is outlined in Section 3. Sections 4 and 5 present the quantitative and qualitative findings of the empirical enquiry. Section 6 discusses the key findings of the analysis and highlights the contribution to the scholarship. The final section concludes.

The Court’s jurisprudential shift in citizenship has received notable attention in recent decades. In its classic citizenship jurisprudence, the Court opted for an expansive interpretation of citizenship provisions to widen the scope of citizenship rights and to grant economically inactive citizens access to social assistance. In a stark departure from this approach, the Court in cases dealing with comparable facts delivered in the mid-2010s adopted a more restrictive interpretation of citizenship provisions, emphasising the limits and conditions of such rights, which resulted in the refusal of social benefits for certain groups of economically inactive citizens. Scholars have rightly observed that this phenomenon is not an isolated instance by pointing to a broader trend in the change of outcomes (Blauberger et al. 2018; Šadl and Sankari 2017; Davies 2018).

In the process of making the shift more intelligible, the scholarship has predominately focused on understanding the motivations behind it. The shift has been so far accounted for based on both legal and extra-legal considerations. Scholars have attributed the jurisprudential shift to the ideological transformation of the Court (Iliopoulou-Penot 2016; Thym 2015; Spaventa 2017; NicShuibhne 2015) by showing that the shift is not the direct result of the introduction of Directive 2004/38 (the Directive),15 but rather systemic (Thym 2015; NicShuibhne 2015). For Davies the change in outputs stems from the change in inputs as, he argues, the litigants in recent cases are less meritorious (Davies 2018). A bourgeoning strand of the scholarship underlines the role of extra-legal factors rooted in the political context such as the financial crisis, and Brexit, in arguing that such events pressured the Court to prioritise the interests of Member States over those of individuals (Šadl and Madsen 2016; Schmidt 2017; Reynolds 2017).

Despite the overwhelming emphasis on the causal dimension of the shift, its lasting legacy remains understudied. Scholars speculated that the shift would have a lasting impact as it “rolls back decades of EU citizenship construction” (Minderhoud and Mantu 2017, 207) and that this approach “will be difficult to reverse” (Šadl and Sankari 2017, 109). On the other hand, the importance placed on contextual factors could be interpreted as leaving open the possibility for a return to the earlier approach if and when the political climate becomes more conducive to the judicial expansion of European social citizenship. Existing scholarship has yet to empirically address the permanence of the shift with most accounts containing the analysis to cases delivered until 2016 (Šadl and Madsen 2016; Šadl and Sankari 2017; O’Brien 2017; Davies 2018). Given the revival of social Europe, following the introduction of the European Pillar of Social Rights in 2017, it is of interest to empirically examine to what extent the Court’s approach to European social citizenship moves with the political tides.

The citations included in judgments provide a good access point for addressing this gap identified in the scholarship. The Court’s citations have already been operationalised to study the value of precedential constraint in EU law (Panagis and Šadl 2015), the mutation of the common market and methods of European integration (Šadl, López Zurita, and Piccolo 2023), as well as the Court’s interaction with its political audience (Larsson et al. 2017). The Court’s references to its earlier jurisprudence have also been relied upon to determine the most authoritative or important cases (Derlén and Lindholm 2014; Madsen and Šadl 2016). Notably, the work of Šadl and Sankari highlights the link between the reference frame and the Court’s jurisprudential shift in citizenship (Šadl and Sankari 2017). Their analysis of 38 cases delivered until the end of 2016 shows that the Court is replacing references to the classics with references to rights-limiting precedents (Šadl and Sankari 2017). An analysis of citations, uncovering the most authoritative cases and qualitatively analysing the reference frame of citizenship judgments could, therefore, elucidate broader trends in the Court’s interpretation of citizenship provisions and the evolution of European social citizenship across time.

Explicit references to earlier decisions are a common feature of judicial decisions which link the case at hand to past and future judgments. The Court is no exception as citations are a well-established part of its judgments (Jacob 2014). Even though the Court often does not engage in detail with its past decisions, as is customary in common law traditions, it has developed a consistent approach to referencing its previous case-law (Komárek 2009). The Court’s approach to citations favours a collective and apodictic reference style by listing cases in strings at the end of the paragraph in support of the conclusion reached (Jacob 2014; Derlén and Lindholm 2014). According to Jacob, the in-house recommendations encourage the Court to cite no more than three cases, ideally a mixture of the first and most recent judgments dealing with the specific point of law (Jacob 2014, 101). It follows that despite the emergence of new cases, older cases which established important principles are expected to appear in citation strings. Given that the Court greatly abstains from openly overruling past decisions, the judgments cited are perceived as important authorities for the case at hand (Derlén and Lindholm 2014; Jacob 2014). The Court’s well-established referencing style deems citations a good indicator of a jurisprudential shift due to the preservation of older cases in the reference frame and the assumption that the cited cases reflect the Court’s reasoning. To account for the rare instances where the Court references an earlier judgment with the intention of overruling it, such as in Metock16 where the Court referenced Akrich17 to signal its departure from the conclusion reached there (Komárek 2009), the network analysis is combined with a legal, qualitative analysis of citations.

The article combines network methods and legal doctrinal analysis to empirically examine the evolution of the Court’s reference frame through the lens of citations. The analysis examines all 203 judgments delivered by the Court on citizenship matters up to and including October 2023.

The network analysis of citations is based on the metadata publicly available on Curia.18 Citations to case-law were extracted from the list enumerating the documents cited in each judgment. The observations are limited to only judgments and orders issued by the Court, excluding references to the Treaties, legislation, judgments of the General Court, and opinions of Advocate Generals from the scope of the enquiry. The relevant information was not available on the Curia website for all judgments, especially for those delivered after June 2023. Therefore, the network analysis only considers judgments for which data on citations was published on the Curia website when the analysis was conducted in November 2023.

The data was used to construct two citation networks using the software Gephi,19 connecting a judgment (node) to all the judgments it cites (edges) and mapping the various inter-connections. Gephi visualises citations as figurative models, flashing out how a single case is linked to other cases in the network and singling out judgments that are central to this network (Byrne, Gammeltoft-Hansen, and Olsen 2023). According to Šadl and Olsen, by studying the incoming citations, cases which are central to the structure can be identified in a systematic manner as they accumulate a higher importance score (Šadl and Olsen 2017). The enquiry relies on citation count (in-degree) to measure case importance.

It is expected that older cases, such as the citizenship classics, will accumulate citations across time as the selected measure is biased in favour of older cases (Šadl and Olsen 2017). To address this issue, two networks capturing two different periods are constructed and compared. The first network considers all citizenship cases delivered until the end of 2015, while the second one captures the period from 2016 until October 2023. The selected cut-off point allows for a more comprehensive analysis of the impact of cases such as Brey, Dano and Alimanovic, which are perceived as instrumental to the shift. These cases, having been delivered before 2016, are placed on the same starting point in the second network as the classics. Furthermore, given that most scholarly accounts examining the Court’s citizenship jurisprudence concerned cases delivered until 2016 (Šadl and Madsen 2016; Šadl and Sankari 2017; O’Brien 2017; Davies 2018), the selected cut-off point can illustrate whether the trends observed by scholars from the analysis of cases delivered before 2016 continue in recent years. The network approach is supplemented by a quantitative analysis of references to the classics and the restrictive line of cases by tracking the citations they received across time.

The legal analysis of citations complements the quantitative findings by qualitatively examining the Court’s references to its previous case-law. The doctrinal analysis sheds light on the Court’s way of referencing its earlier judgments and the weight of individual citations, namely whether a case is cited in support of the conclusion reached, is distinguished, or is mentioned without contributing to the legal discussion. The legal analysis is informed by the rich body of work examining citation practices at the Court which alludes to four types of explicit references to earlier jurisprudence. The first two originate from the common law tradition and include references to earlier case-law to support a conclusion reached or, conversely, to distinguish the case cited from the case at hand (Komárek 2009). The other two are informed by the work of Šadl and Sankari, which reveals that the Court can cite its earlier case-law as “opening-line” and “reinterpretation” references (Šadl and Sankari 2017, 101). Drawing on the work of Šadl and Sankari, opening-line references denote citations which provide a prelude to the analysis and “do not contribute to the ensuing actual legal discussion” (Šadl and Sankari 2017, 100–101). Opening-line references tend to appear in the first paragraphs of the Court’s reasoning and often concern a general legal proposition which is not directly linked to the particular facts of the dispute. Reinterpretation references include instances where the Court cites together cases with conflicting rationales and outcomes in support of the same proposition (Šadl and Sankari 2017, 101). A reinterpretation reference is identified by instances where, for example, the classics, such as Martínez Sala, appear in the same citation string as the restrictive line of cases to support a restrictive interpretation of European citizenship and the refusal of social assistance. In such instances, the fact that the applicant in Martínez Sala was granted social assistance appears immaterial, and the meaning of Martínez Sala is altered, or more accurately, re-interpreted. Through this prism, the legal analysis attempts to qualitatively examine patterns emerging from the Court’s reference frame across time.

A mixed methods approach is selected to optimise the accuracy of the findings. On the one hand, the use of network analysis contains the selection bias in determining the importance of cases which is inherent in doctrinal approaches (Byrne, Gammeltoft-Hansen, and Olsen 2023; Šadl and Olsen 2017). The strengths of the citation network analysis rest in the ability to “ensure the reproducibility, generalizability, and empirical validity of doctrinal studies” (Šadl and Olsen 2017, 330) and to unearth hidden patterns (Byrne, Gammeltoft-Hansen, and Olsen 2023). On the other hand, the doctrinal analysis is relied upon to counter the limitations of the network approach, namely the fact that all citations are treated equally, without distinguishing whether the case was cited as an authority or was overruled (Šadl and Olsen 2017). Lastly, as the citation network analysis constructs a static picture, the doctrinal analysis will focus on flagging the dynamic process behind it. The mixed methods approach, therefore, allows for a more nuanced understanding of the evolution of the reference frame of citizenship judgments by distinguishing permanent changes from the expected ebb-and-flow.

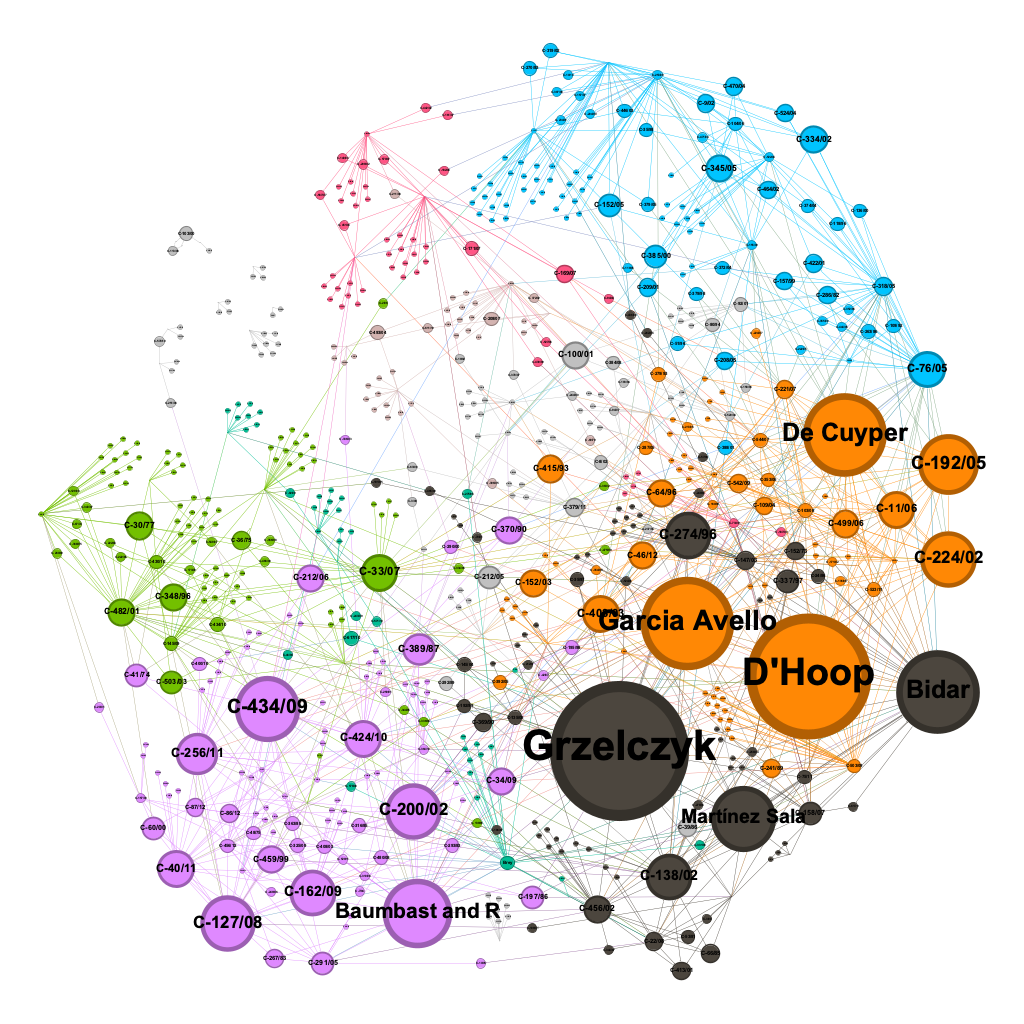

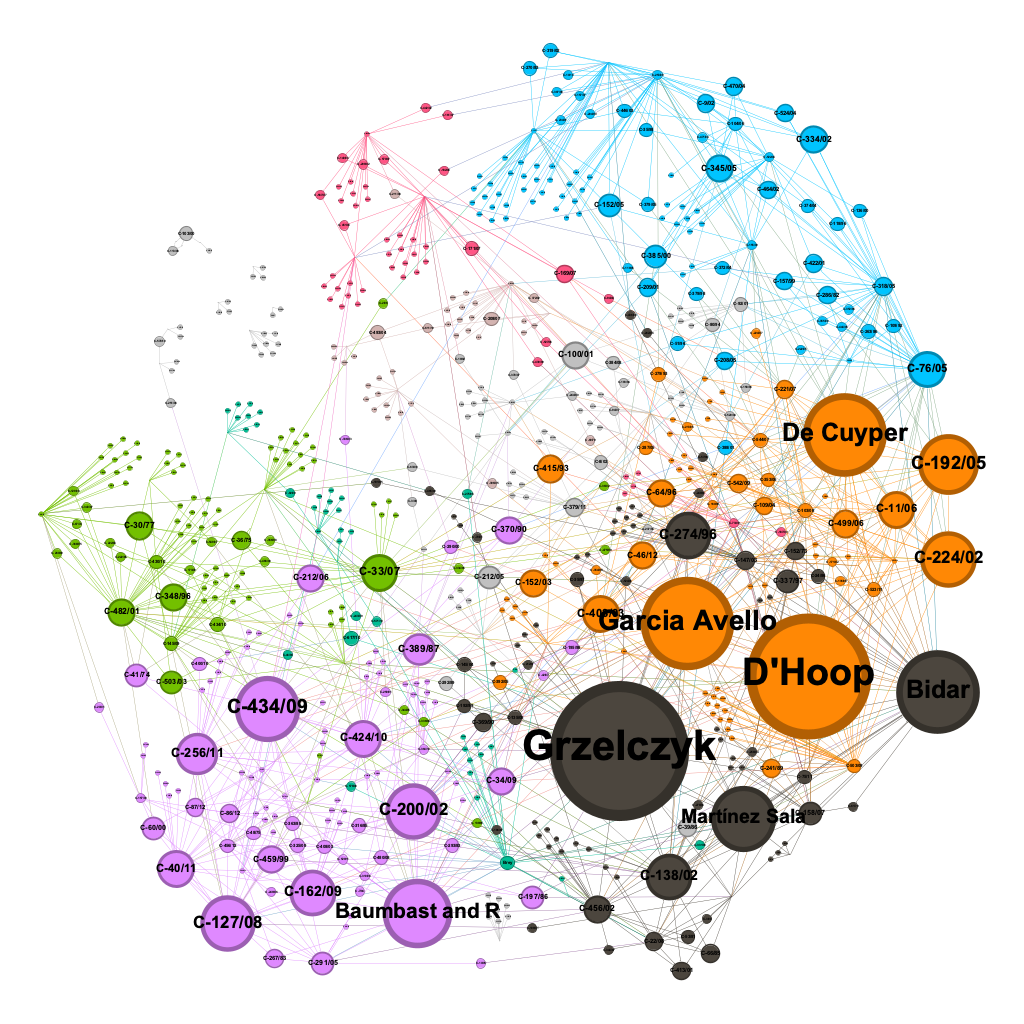

The findings of the network analysis are displayed in Network 1 (Figure 1) and Network 2 (Figure 2). Network 1 provides a visualisation of the citations in citizenship judgments delivered from 1997 until 2015, while Network 2 presents the citations in citizenship judgments delivered from 2016 until October 2023. Network 1 consists of 667 nodes and 1315 edges while Network 2 has 452 nodes and 776 edges. The size of the nodes is representative of the in-degree score of the case. Community detection techniques were also relied upon to uncover connections between cases. Cases which share the same colour belong to the same community, meaning they have more connections with each other and keep citing each other more than other cases. The network analysis is supplemented by a quantitative analysis of the citations received by the classics and the restrictive line of cases across time, displayed in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

The findings reveal a change in the reference frame of citizenship judgments delivered in the period 2016–2023 compared to those delivered before. A comparison between Network 1 and Network 2 reveals a change in the most cited cases between the two periods. A high in-degree authority score, illustrated by the larger nodes, denotes that the specific case was prominently featured in the reference frame of citizenship judgments delivered during the period reviewed. The network approach facilitates the identification and juxtaposition of the most authoritative cases across time. The most cited judgments in citizenship cases delivered before 2016 were Grzelczyk (30), D’Hoop (27), Garcia Avello20 (20), De Cuyper21 (18) and Bidar (18).22 The most frequently referenced judgments in citizenship decisions delivered from 2016 until October 2023, as illustrated in Network 2, were Rendón Marín23 (15), Grzelczyk (12), Chavez-Vilchez24 (10) and Zambrano25 (10). The comparison of the most authoritative cases in the two networks suggests that the reference frame of citizenship judgments underwent a drastic transformation as all central cases found in Network 1, apart from Grzelczyk, were replaced in Network 2.

The comparison of the two networks further reveals a notable decline in the citations received by the Court’s classic jurisprudence in citizenship judgments delivered from 2016 onwards. Apart from Grzelczyk, the citizenship classics did not gather a high in-degree score in the period 2016-2023 despite being prominently featured in the reference frame of citizenship judgments delivered before. All judgments forming part of the Court’s classic jurisprudence gathered high in-degree scores as illustrated by the relatively large nodes in Network 1 representing Grzelczyk (30), D’Hoop (27), Bidar (18), Baumbast (15) and Martínez Sala (14). Conversely, in Network 2, D’Hoop (1), Bidar (2), Baumbast (3) and Martínez Sala (1) gathered notably lower in-degree scores. Even though Grzelczyk, the most cited judgment in Network 1, remained an important authority in the reference frame of citizenship judgments delivered from 2016 onwards, it is not the most cited judgment in Network 2. The most cited judgment from 2016 onwards as shown in Network 2, is Rendón Marín.

The cases which the scholarship perceives as important milestones of the Court’s turnaround in citizenship, despite not dominating the reference frame of citizenship judgments delivered from 2016 onwards, gathered significantly more citations in Network 2 than in Network 1. The restrictive line of cases is largely absent from the reference frame of citizenship judgments delivered until 2015, as illustrated by the small nodes representing Brey (3), Dano (1), and Alimanovic (0) in Network 1. García-Nieto is entirely absent from Network 1 as it was delivered after the period reviewed. The nodes representing Brey (6), Dano (7), Alimanovic (5) and García-Nieto (3) are noticeably larger in Network 2.

Furthermore, Network 1 is dominated by a small number of central cases, while Network 2 appears more pluralistic, with a relatively larger number of cases gathering a high authority score. This is most likely because Network 2 begins from 2016, ignoring all citations received by older cases prior to that point. Therefore, cases delivered in the first years of the period under review have the same chances as older cases to become central cases. For example, both Zambrano and Chavez-Vilchez gathered an in-degree score of 10 despite being delivered in 2011 and 2017 respectively. The more pluralistic structure of Network 2, therefore, suggests that the advantage granted by the in-degree authority score to older cases is contained and entirely erased for all cases delivered before 2016.

Lastly, a comparison between the two networks suggests that the most authoritative cases in Network 2 are more homogenous than those in Network 1. In Network 1 the central cases are illustrated in different colours, orange and dark grey, while in Network 2 almost all central cases are coloured in blue. The findings reveal that all authoritative cases in Network 2, except from Grzelczyk, belong to the same community and are strongly inter-linked. In fact, the central cases in Network 2, namely Rendón Marín, Chavez-Vilchez and Zambrano, all concern the rights of third-country national (TCN) family members of European citizens. In Network 1 on the other hand, the most central cases are divided into two communities with the first cluster consisting of Grzelczyk, Bidar and Martínez Sala and the second of D’Hoop, Garcia Avello, and De Cuyper. As Gephi does not allow for the same colour to be assigned to the same community in different graphs it is not possible to compare community structures across time through the changes observed in colour clusters.

Figure 1. Network 1. Citations Extracted from Citizenship Judgments Delivered in the Period 1997–2015.

Figure 2. Network 2. Citations Extracted from Citizenship Judgments Delivered in the Period 2016–2023.

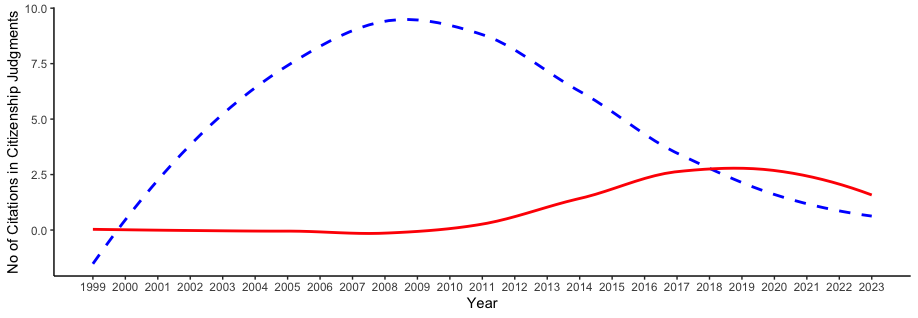

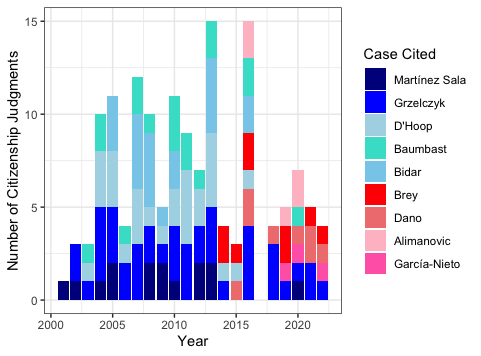

To better understand the interplay between the citizenship classics and the restrictive line of cases, references to both are extracted and compared across time. Figure 3 displays the trends in citations to the classic jurisprudence and restrictive line of cases illustrated by the blue and red lines, respectively. Figure 4 provides a visualisation of the number of citizenship judgments citing each of the cases reviewed per year, with shades of blue corresponding to the classics and shades of red to the restrictive line of cases.

As demonstrated in Figure 3, from 2009 onwards, references to the citizenship classics experienced a decline. Around the same time, citations to the restrictive line of cases were gaining momentum. Citations to the citizenship classics collectively exceeded those to the restrictive cases until 2018. In citizenship judgments delivered during the last four years of the dataset, references to the restrictive cases surpassed those to the classics.

At an individual level, Grzelczyk, is the only judgment from the Court’s classic citizenship jurisprudence that was considerably cited in citizenship judgments delivered after 2016, as illustrated in Figure 4. D’Hoop and Bidar were not cited at all in citizenship judgments delivered after 2016. Martínez Sala was only cited in the Caisse pour l'avenir des enfants26 judgment from 2020, and Baumbast was cited three times after 2015. Figure 4 further illustrates that references to the restrictive cases outnumber those to the classics in recent years. For instance, in 2014, Brey was cited in 2 citizenship judgments, surpassing all citizenship classics as Grzelczyk and D’Hoop were each cited once, while the rest were not referenced at all in citizenship judgments delivered that year. This trend continues in citizenship cases delivered after 2016 as shown in Figure 4. For example, citizenship judgments delivered in 2019 contained no references to the Court’s classic jurisprudence except from Grzelczyk which was cited in TopFit and Biffi.27 In the same year, Alimanovic and García-Nieto were both cited in Tarola,28 while Brey was cited in 2 citizenship judgments.

Figure 3. Citations to the Classic and the Restrictive Cases Across Time.

Figure 4. Citizenship Judgments citing the Classic and the Restrictive Cases Across Time.

The legal analysis of the citations found in citizenship judgments further reveals that the Court’s reliance on its classic jurisprudence is less substantial than the quantitative findings suggest. In citizenship judgments delivered from 2016 onwards, the classics are absent from the reference frame or are cited as opening-line and reinterpretation references. Crucially, when they are substantively cited to justify the legal conclusion reached, they lend support to an expansive interpretation of European social citizenship.

The qualitative analysis suggests that the Court omits references to the classics even in cases where they are relevant to the legal discussion and could have been cited. On a methodological note, all citizenship judgments were reviewed and cases with a thematic overlap to the classics and no references to them were flagged.

An illustrative example of a case with a thematic overlap to the classics but no citations to them is CG,29 delivered in 2021. The dispute in the main proceedings concerned the right of an economically inactive Union citizen to equal access to social assistance in the host Member State. The Court in CG reiterated that the principle of non-discrimination is given specific expression in Article 24 of the Directive in relation to citizens who exercise their freedom of movement and therefore, such situations are not governed by the general discrimination prohibition laid out in Article 18 TFEU.30 On this basis, the Court answers the first question by interpreting Article 24 of the Directive as not precluding national legislation from excluding from social assistance economically inactive Union citizens who do not have sufficient resources and to whom that State has granted a temporary right of residence, where those benefits are guaranteed to nationals of the Member State concerned who are in the same situation.31 The Court does not refer to its early jurisprudence despite the evident factual similarities between CG and cases such as Martínez Sala. The reference frame is instead overwhelmingly dominated by Dano with various paragraphs being cited in total 9 times. References to Dano in CG appear to replace the Court’s classic cases, such as Grzelczyk and Martínez Sala. For example, the Court justifies the fundamental status of Union citizenship by referencing paragraphs 57 and 58 of Dano and the case-law cited,32 as opposed to explicitly citing Grzelczyk. It is worth noting that in paragraph 58 of Dano, the Court cites two of the classics, Grzelczyk and D’Hoop in support of the same principle.33 The Court’s substitution of direct references to Grzelczyk and D’Hoop with an indirect reference therefore suggests that the classics are not cited despite being relevant to the legal discussion.

The qualitative analysis further reveals that citations to the classics found in citizenship judgments delivered from 2016 onwards often appear in the context of opening-line references. Citizenship judgments citing the classics were singled out and all citations to the classics were qualitatively examined. The analysis revealed that the classics were often cited as opening-line references in recent judgments. This was particularly the case with regards to Grzelczyk, the only judgment from the Court’s classic jurisprudence consistently cited after 2015. For example, in TopFit and Biffi the Court’s analysis begins with a reference to paragraph 31 of Grzelczyk to emphasise the fundamental status of Union citizenship.34 The citation to Grzelczyk had little to no bearing on the legal discussion as the case concerned amateur sports and whether Article 21 TFEU can generate legal obligations for associations or organisations that do not come under public law. The qualitative analysis of references to the classics, therefore, adds some nuance to the quantitative findings in explaining the high authority score of Grzelczyk in Network 2.

The qualitative analysis further reveals that the Court tends to cite the classics as reinterpretation references, particularly in recent citizenship judgments. The analysis of all citizenship judgments which contained citations to both the classics and the restrictive line of cases demonstrated that references to both often appear in the same citation string. The findings are in line with the observations of Šadl and Sankari in that the classics continue to be cited in the same citation string as newer cases, which stand for different legal propositions and lead to different outcomes than the classics (Šadl and Sankari 2017, 100–101). For example, Grzelczyk is cited twice by the Court in Familienkasse35 in a string followed by newer cases with opposite outcomes. Paragraph 31 is cited together with CG in support of the principle that “the status of citizen of the Union is destined to be the fundamental status of nationals of the Member States, enabling those among such nationals who find themselves in the same situation to enjoy the same treatment in law irrespective of their nationality, subject to such exceptions as are expressly provided for in that regard”.36 The cited paragraph of CG emphasises the exceptions to equal treatment flowing from Article 20 TFEU with a citation to Dano paragraphs 57 and 58 and the case-law cited.37 As already discussed, the Court in CG reached a restrictive interpretation of European citizenship leading to the refusal of social assistance for an economically inactive citizen. Against this backdrop, the pairing of the two judgments suggests that the Court was paving the way for diverging from the expansive approach adopted in Grzelczyk without explicitly overruling it.

In the rare instances where the Court engages with its classic jurisprudence, the outcomes tend to favour an expansive interpretation of European social citizenship. An illustrative example of the classics being substantially cited to support an expansive interpretation of European social citizenship is Jobcenter Krefeld.38 In Jobcenter Krefeld, the Court departed from its restrictive line of cases and clarified that national legislation is precluded from automatically and in all circumstances excluding from benefits a national of another Member State and his or her minor children all of whom have a right of residence by virtue of those children attending school in that Member State. The Court also confirmed that the right of equal access to education of the child of a migrant worker in the host Member State, which continues even after the parent loses the worker status, is not called into question by Article 24(2) of the Directive.39

The Court’s reference frame in Jobcenter Krefeld appears to be an outlier in that first the Court cites cases to distinguish them, and second it extensively relies on the classics to support the conclusion reached. Even though the restrictive line of cases is featured in the reference frame, such cases do not contribute to the legal analysis and outcome. Instead, the Court adopts an unusual approach by explicitly distinguishing such cases from the case at hand. For example, the Court emphasises that “[t]he situation which arises in the present case must also be distinguished from that at issue in the case that gave rise to the judgment of 11 November 2014, Dano”40 before spelling out the reasons for distinguishing the two. The same pattern resurfaces in relation to both Alimanovic and García-Nieto as the Court firmly asserts that “the situation which arises in the present case must be distinguished from those at issue in the cases that gave rise to the judgments of 15 September 2015, Alimanovic […]and of 25 February 2016, García-Nieto and Others […], where the applicability of that derogation led the Court to recognise a corresponding derogation from the principle of equal treatment laid down in Article 4 of Regulation No 883/2004”.41 The Court’s detailed engagement with the restrictive line of cases marks a stark departure from its preferred citation style and suggests that the conclusion reached calls for greater justification. The Court relied extensively on one of the classics, Baumbast to support the legal outcome. Baumbast was cited a total of 3 times in support of various analytical steps in the Court’s reasoning.42 The Court again departs from the identified trends in its reference of the classics in recent judgments, as Baumbast is cited in a manner akin to precedence as opposed to an opening-line or reinterpretation reference. It is worth noting that Baumbast was last cited in a citizenship judgment in 2016.

The findings collectively suggest that the reference frame of citizenship judgments delivered from 2016 onwards is starkly different from that found in judgments delivered before. The findings reveal three key insights. First, the analysis of the citations found in citizenship judgments across time suggests that the Court’s jurisprudential shift in citizenship extends beyond the expected jurisprudential ebb-and-flow. Second, the findings of the qualitative analysis indicate that the shift is not only fundamental but perhaps also strategic. Lastly, the analysis of the citations in judgments delivered from 2016 qualifies the influence of the Court’s restrictive approach to the social dimension of European citizenship. The Court appears to be expanding the scope of citizenship rights in cases concerning the rights of European citizens and their TCN family members while at the same time adopting a more restrictive approach in cases encroaching upon the social dimension.

Some changes in the reference frame are expected due to the evolution of the legal doctrine and the emergence of newer judgments. Nonetheless, the findings reveal a fundamental change in the reference frame of citizenship judgments across time which extends beyond the regular jurisprudential ebb-and-flow. The juxtaposition of the two citation networks revealed a fundamental change in the most cited judgments and a decline in references to the classics. The qualitative analysis supports the finding of a fundamental change in the reference frame of citizenship judgments from 2016 onwards by highlighting that references to Grzelczyk, the only judgments from the classics consistently cited after 2015, are mostly in the form of opening-line references. The frequent citations to Grzelczyk could be attributed to its elevated status, as the Court in that judgment first proclaimed the fundamental status of European citizenship. According to the scholarship, a judgment such as Grzelczyk, which “establishes a legal rule or principle that is employed to resolve future issues” is perceived as an important source of law and is thus distinguished from other cases (Derlén and Lindholm 2014). It is therefore unsurprising that the Court continues to cite this judgment which is seminal for European citizenship. Nonetheless, as already discussed, despite being cited in recent citizenship judgments, Grzelczyk does not often play a part in the legal conclusion as it is mostly cited as an opening-line reference. Consequently, the findings suggest that the shift observed in the reference frame is fundamental despite the high volume of citations to Grzelczyk during the second period reviewed.

The Court’s declining reliance on the citizenship classics could be explained by two competing rationales. The findings could be interpreted as suggesting that the classics are being phased out due to the development of European citizenship law. It is true that the legal landscape of European citizenship changed since the delivery of the classics. The entry into force of the Directive in 2006 postdates the delivery of the last judgments of the Court’s classic jurisprudence, Bidar, in March 2005. It is therefore possible that the legal relevance of the citizenship classics was eroded as they primarily concern the interpretation of the Treaties and legislative instruments which were repealed by the Directive. Yet, this interpretation is not supported by an analysis of the Court’s case-law, as the classics were extensively referenced even in judgments where the Court was asked to interpret the Directive. An illustrative example is Brey, where the Court included 9 references to Martínez Sala, Grzelczyk, Baumbast, and Bidar collectively to support the interpretation afforded to the provisions of the Directive. Baumbast was referenced in support of the proposition that “the conditions laid down in Article 7(1)(b) of Directive 2004/38 must be construed narrowly […] and in compliance with the limits imposed by EU law and the principle of proportionality”.43 Similarly, citations to both Grzelczyk and Bidar supported the Court’s interpretation of the Directive as recognising a certain degree of financial solidarity between nationals of a host Member State and nationals of other Member States.44 The Court’s reliance on its classic jurisprudence in the process of interpreting the Directive is noted by scholars who trace the Court’s reading of the Directive’s aim as facilitating the exercise of the primary and individual right to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member States to the interpretation given to Regulation (EEC) No 1612/6845 in Baumbast (Šadl and Sankari 2017, 96). In light of this, the Court’s decreasing reliance on the classics cannot be seen as the direct result of the introduction and entry into force of the Directive.

Furthermore, the Court’s distinct approach to citations preserves older cases in the reference frame despite the emergence of newer cases addressing the same legal issues. As already discussed, the standard practice at the Court is to cite around three cases in a citation string including the first case in which the principle stated emerged along with newer cases (Jacob 2014). The Court’s classic jurisprudence which established important doctrines such as the applicability of the non-discrimination principle to economically inactive citizens in Martínez Sala46 and first proclaimed the fundamental status of citizenship in Grzelczyk is expected to be of legal relevance in present disputes. Therefore, the fundamental change observed in the reference frame of citizenship judgments, particularly the phasing out of the classics, extends beyond expected jurisprudential fluctuations.

A more convincing explanation for the decreasing reliance on the classic citizenship jurisprudence could be the change in the Court’s approach to citizenship rights, particularly its understanding of European social citizenship. Literature on judicial tactics suggests that a tendency to cite new judgments could indicate that a court is changing its doctrine, and in this process, older judgments become obsolete (Dothan 2014). Given the scholarly consensus as to the Court’s jurisprudential shift toward a more restrictive interpretation of citizenship rights in the mid-2010s, it is possible that the reference frame was altered to justify this restrictive approach. The findings of Šadl and Sankari of a new reference frame in judgments delivered until 2016 suggest that “rights-closing reference points such as Brey have practically replaced the classic rights-opening reference points in the argumentative parts” to support the refusal of social assistance to economically inactive citizens (Šadl and Sankari 2017, 109). The findings of the current empirical enquiry, demonstrating that references to the restrictive line of cases are gradually replacing those to the classics, are in line with the conclusions of Šadl and Sankari and further suggest that the observed trends continue after 2016.

Building on the previous insight, the empirical enquiry further suggests that the observed change in the reference frame is not only fundamental but potentially strategic. The qualitative analysis reveals that the classics were not cited even when they were relevant to the legal discussion and could have been cited. According to Šadl, the Court tends to repeat the same legal statement while substituting the cases included in citation strings to justify the opposite outcomes reached (Šadl 2021). The omission of the classics in judgments where they were legally relevant could indicate that the Court was purposefully abstaining from citing them in citizenship judgments delivered in recent years as the restrictive interpretation of European citizenship provisions could hardly be supported by the expansive approach of early cases such as Grzelczyk and Martínez Sala.

This is further supported by the indirect reference to Grzelczyk in CG where the Court repeated the famous line from Grzelczyk about the fundamental status of citizenship by citing Dano. In doing so, the Court dissociated the legal proposition from the foundational case and the factual circumstances in which it first appeared (Šadl 2021, 1782). This in turn facilitates the justification of the outcome in CG which is in line with Dano but diverges considerably from that in Grzelczyk. A similar effect of justifying divergent outcomes is also achieved by reinterpretation references, as the Court by co-citing cases with opposing outcomes justifies contrasting interpretations and divergent outcomes (Šadl 2021, 1778). By citing together in a citating string the classics and the restrictive line of cases, the Court was able to justify the refusal of social assistance while referencing its classic jurisprudence.

The interplay between references to the classic jurisprudence and the restrictive cases suggests that the Court is strategically citing the classics to support expansive interpretations of social rights and the restrictive cases to refuse social assistance. On the one hand, the dominance of the restrictive line of cases over the classic jurisprudence in the reference frame of citizenship judgments delivered from 2016 onwards reveals the Court’s continued reluctance to grant social rights to economically inactive citizens in the host Member State. The Court’s initial turnaround from an expansive to a restrictive interpretation of European citizenship in the restrictive line of case was closely linked to the increasing politicisation of free movement and growing fears of benefit tourism and welfare migration (Blauberger et al. 2018). The Court’s restrictive approach in cases concerning the entitlement of economically inactive citizens to social assistance in the host Member State through references to the restrictive line of cases could therefore be perceived as an attempt to respond to debates on welfare migration.

On the other hand, the analysis of the reference frame in Jobcenter Krefeld suggests that the classics are relied upon to justify the grant of social rights to economically inactive citizens. The Court in Jobcenter Krefeld does manage to stray from the Dano path and reaches a pro-individual outcome, yet that required additional analytical steps and an extensive reliance on one of the classics, Baumbast. In Jobcenter Krefeld the Court carefully distinguished the facts of the present dispute from those giving rise to the restrictive line of cases on the basis that the applicant in Jobcenter Krefeld had worked in the host Member State before becoming unemployed.47 The Court addresses welfare migration concerns by highlighting the limited scope of the right to equal access to social assistance granted in Jobcenter Krefeld. The right is only available if the parent of the child attending school has entered the labour market of the host Member State and ends when the child completes their studies.48 Furthermore, instances where the jobseeker entered the host Member State in order to seek initial employment,49 or where there is a proven abuse of law are also excluded from the scope of such rights.50 The analysis of the Court’s reasoning in Jobcenter Krefeld, therefore, suggests that it is possible to diverge from the restrictive approach of cases such as Dano and Alimanovic. Yet, an expansive interpretation of social rights requires better justification. The findings confirm the warnings of scholars that the restrictive interpretation of European social citizenship stemming from the Dano line of cases would be challenging to reverse (Šadl and Sankari 2017). Crucially, the analysis of the reference frame in Jobcenter Krefeld further reiterates the Court’s strategic way of referencing the citizenship classics and the restrictive line of cases.

The analysis of the reference frame of all citizenship judgments delivered by the Court qualifies the influence of the restrictive line of cases. It suggests that their prominence is only observable in cases concerning the social dimension of European citizenship. As illustrated in Network 2, citations to the restrictive line of cases are relatively low compared to other cases such as Rendón Marín, Zambrano, and Chavez-Vilchez. The influence of the restrictive cases does exceed that of the citizenship classics yet compared to other cases is relatively contained. The findings suggest that the dominance of the restrictive line of cases is only observable in the reference frame of judgments dealing with the social dimension of European citizenship.

The analysis of the most central cases in the period 2016–2023, singled out by the network analysis, suggests that the Court still interprets aspects of European citizenship in an expansive manner. The cases which are central to Network 2, such as Rendón Marín, Zambrano, and Chavez-Vilchez, are generally characterised by an expansive approach as the Court extended the scope of citizenship rights. Zambrano is known for extending the scope of citizenship rights by interpreting Article 20 TFEU as precluding Member States from adopting decisions which deprive citizens of “the genuine enjoyment of the substance of the rights” conferred by Union citizenship.51 In the aftermath of Zambrano, the Court delivered McCarthy,52 and Dereci,53 which limited the scope of citizenship rights flowing from Article 20 TFEU (NicShuibhne 2012). Subsequent cases such as Rendón Marín and Chavez-Vilchez restored hope in the Zambrano formula as a rights generator by lowering the threshold for satisfying the substance of rights test. In Chavez-Vilchez the Court held that “the fact that the other parent, who is a Union citizen, is actually able and willing to assume sole responsibility for the primary day-to-day care of the child is a relevant factor, but it is not in itself a sufficient ground”54 for a refusal of a derived right of residence under Article 20 TFEU. In a similar vein Rendón Marín interprets Article 20 TFEU as precluding the automatic refusal of the grant of a residence permit to a TCN sole carer of minor Union citizens on the sole ground that he or she has a criminal record where the refusal has a consequence of requiring the children to leave the territory of the EU.55

The social dimension, specifically the conditions under which Union citizens are entitled to receive social assistance in the host Member State, was not explicitly addressed in any of these cases. In fact, as the community detection analysis also highlighted, almost all central cases in Network 2 concerned the rights of TCN family members of Union citizens. As expected, these cases were extensively cited in subsequent judgments to extend the scope of the ancillary rights enjoyed by TCN family members of Union citizens. For example, in Lounes, where the scope of Article 21 TFEU was extended to TCN family members of naturalised free-movers, the Court relied on Rendón Marín to justify the need to grant a TCN family member of a Union citizen in such circumstances a derived right of residence to guarantee the effectiveness of the rights under Article 21(1) TFEU.56 The numerous references to cases such as Rendón Marín, Zambrano, and Chavez-Vilchez in citizenship judgments delivered after 2016 suggest that the Court continues to expand the scope of citizenship rights, although not the social dimension. As already highlighted by the example of CG, the reference frame of recent citizenship judgments concerning entitlements to social assistance is dominated by the Dano line of cases. In fact, CG contains no references to Rendón Marín, Chavez-Vilchez, or Zambrano, which the network analysis singles out as central reference points in citizenship judgments delivered from 2016 onwards.

This article revisits the Court’s jurisprudential shift in citizenship through the prism of citations. It focuses on the social dimension of European citizenship by examining references to the Court’s classic citizenship jurisprudence, known for its expansive interpretation of citizenship rights, and cases delivered in the mid-2010s where the Court emphasised the limits for accessing social assistance in the host Member State. The analysis of the citations found in citizenship judgments through a mixed methods approach illuminates broader trends and detailed twists in the Court’s interpretation of European citizenship in general and European social citizenship in particular.

The article contributes to the scholarship examining the Court’s jurisprudential shift in citizenship by focusing on its lasting impact. The findings suggest that the Court’s turnaround in European social citizenship extends beyond the expected jurisprudential ebb-and-flow. This conclusion is supported by the absence of the classics from the reference frame of citizenship judgments delivered from 2016 until 2023 despite being extensively referenced prior to that point. The analysis of the citations included in citizenship judgments delivered from 2016 onwards empirically confirms the scholarly hunches as to the legacy of the Court’s jurisprudential shift (NicShuibhne 2015; Šadl and Sankari 2017). The Court’s turnaround in European social citizenship is not confined to the cases delivered in the mid-2010s. The analysis of the reference frame of citizenship judgments delivered from 2016 until 2023 demonstrated that citations to cases in which the Court restricts the social dimension of European citizenship exceed those to the classic jurisprudence. The findings build on the conclusions of Šadl and Sankari (Šadl and Sankari 2017) and demonstrate that the observed trends as to the Court’s reference frame continue after 2016 and up until 2023. Although it is possible for the Court to depart from the trajectory of the restrictive line of cases, it is arguably harder to do so, as illustrated by the careful reasoning and detailed engagement with earlier cases in Jobcenter Krefeld.

The qualitative analysis further reveals that the shift is not only systemic but also potentially strategic. The qualitative analysis of references to the Court’s classic jurisprudence in citizenship judgments before and after 2016 rules out the possibility of the shift being the direct result of the introduction and entry into force of the Directive. The Court relied on its classic jurisprudence to interpret the provisions of the Directive on numerous occasions and even did so in Brey, a case perceived as instrumental to the jurisprudential shift. The analysis by flagging instances where the classics could have been cited but were not, suggests that the phasing out of the classics could have been strategic. This is further reiterated by the opening-line and reinterpretation references to the classics. The classics are often referenced in an almost ornamental fashion without substantially contributing to the legal discussion or are cited in a string with the rights-closing cases leading to the justification of a restrictive interpretation of European social citizenship. In the rare instances where the classics play a part in the legal analysis in judgments delivered from 2016 onwards, they are relied upon to justify an expansive interpretation of citizenship provisions with financial spillovers.

The findings further reveal that the Court continues to develop the scope of citizenship rights, particularly in relation to the residence rights of TCN family members of Union citizens. Yet, this expansive approach is not observed in cases concerning the entitlement of economically inactive citizens to social assistance. In cases where the social dimension of European citizenship is addressed, the influence of the restrictive line of cases is evident as references to the Dano line of cases outnumber those to the classics. The analysis of the references to the most authoritative cases from 2016 onwards reveals that the Court’s dynamic stance is still observed in other sub-fields of European citizenship. The findings, by illustrating a disparity in cases delivered from 2016 until 2023 between an expansive approach in cases concerning the residence rights of TCN family members of Union citizens and the restrictive interpretation of the social dimension of European citizenship, pave the way for further research on this topic.

The analysis crucially adds some nuance to the scholarly debate on the causes of this jurisprudential shift. The mixed methods approach revealed that the Court’s turn in citizenship is more fundamental than the scholarship suggested. On the one hand, the withering away of the classics from the reference frame after 2015 and the Court’s tactful references to them casts doubt on Davies’ account, attributing the shift to the less deserving litigants of later years (Davies 2018). On the other hand, the timing of the declining references to the classic jurisprudence provides support for accounts attributing the shift to extra-legal considerations. The declining trend in the references to the classics first emerged in 2009, around the same time as the pressure from the Eurozone crisis was felt by Member States. The analysis of the reference frame of cases delivered from 2016 onwards suggests that the Court, at least in cases with financial repercussions for Member States, adopts a more restrictive approach. The findings further suggest that even though the pressure from contextual factors has, to a large extent, subsided the Court has yet to return to its pre-Dano understanding of European social citizenship.

Lastly, the analysis provides an insight into judicial behaviour, particularly the responsiveness of the Court to political developments. Political science scholars have attributed the Court’s jurisprudential shift in social citizenship to the politicisation of free movement and demonstrated how the Dano line of cases reflected changing public debates about European citizenship in the 2010s (Blauberger et al. 2018). Given the Court’s responsiveness to the political mood, it could be argued that the Court would be expected to return to its earlier expansive approach when the political tides turn. Nonetheless, the empirical data does not support this assumption, as despite the revival of social Europe since 2017 the Court has yet to abandon the Dano approach in favour of its classic jurisprudence. The Court’s reasoning in Jobcenter Krefeld from 2020 could be interpreted as a glimpse of hope by planting the seeds for an incremental return to the expansive approach of the classic jurisprudence. A more pessimistic reading of Jobcenter Krefeld, on the other hand, suggests that the approach followed in the restrictive line of cases is hard to reverse as illustrated by the Court’s careful reasoning and detailed engagement with its earlier case-law. Therefore, as of now, it would be premature to declare that the Court is returning to its classic citizenship jurisprudence and the ideal of European social citizenship that these cases represent. The trajectory of European social citizenship appears to be primarily determined by the restrictive line of cases.

I thank Dorte Martinsen for providing helpful comments to an earlier version of this paper and the participants of the EuSocialCit conference 2024 for their constructive feedback. I also thank Urška Šadl for the constant support and supervision.

Blauberger, Michael, Anita Heindlmaier, Dion Kramer, Dorte Sindbjerg Martinsen, Jessica Sampson Thierry, Angelika Schenk, and Benjamin Werner. 2018. ‘ECJ Judges Read the Morning Papers. Explaining the Turnaround of European Citizenship Jurisprudence’. Journal of European Public Policy 25 (10): 1422–1441. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1488880.

Byrne, William Hamilton, Thomas Gammeltoft-Hansen, and Henrik Palmer Olsen. 2023. ‘Network Analysis and Comparative Migration Law: Examples from the European Court of Human Rights’. International Journal of Migration and Border Studies 7 (2): 197–213. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMBS.2023.128598.

Davies, Gareth. 2018. ‘Has the Court Changed, or Have the Cases? The Deservingness of Litigants as an Element in Court of Justice Citizenship Adjudication’. Journal of European Public Policy 25 (10): 1442–1460. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1488881.

Derlén, Mattias, and Johan Lindholm. 2014. ‘Goodbye van Gend En Loos, Hello Bosman: Using Network Analysis to Measure the Importance of Individual CJEU Judgments’. European Law Journal 20 (5): 667–687. https://doi.org/10.1111/eulj.12077.

Dothan, Shai. 2014. Reputation and Judicial Tactics: A Theory of National and International Courts. Cambridge University Press.

Dougan, Michael. 2013. ‘The Bubble That Burst: Exploring the Legitimacy of the Case Law on the Free Movement of Union Citizens’. In Judging Europe’s Judges: The Legitimacy of the Case Law of the European Court of Justice, edited by Maurice Adams, Henri de Waele, Johan Meeusen, and Gert Straetmans. Hart Publishing. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474200257.

Iliopoulou-Penot, Anastasia. 2016. ‘Deconstructing the Former Edifice of Union Citizenship? The Alimanovic Judgment’. Common Market Law Review 53 (4): 1007–1035. https://doi.org/10.54648/cola2016091.

Jacob, Marc. 2014. Precedents and Case-Based Reasoning in the European Court of Justice: Unfinished Business. Cambridge University Press.

Jesse, Moritz, and Daniel William Carter. 2020. ‘Life after the “Dano-Trilogy”: Legal Certainty, Choices and Limitations in EU Citizenship Case Law’. In European Citizenship under Stress, edited by Nathan Cambien, Dimitry Kochenov, and Elise Muir, 135–169. Brill | Nijhoff. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004433076_008.

Kilpatrick, Claire. 2023. ‘The Roaring 20s for Social Europe. The European Pillar of Social Rights and Burgeoning EU Legislation’. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research 29 (2): 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/10242589231169664.

Komárek, Jan. 2009. ‘Precedent and Judicial Lawmaking in Supreme Courts: The Court of Justice Compared to the US Supreme Court and the French Cour de Cassation’. Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies 11: 399–433. https://doi.org/10.5235/152888712802730602.

Larsson, Olof, Daniel Naurin, Mattias Derlén, and Johan Lindholm. 2017. ‘Speaking Law to Power: The Strategic Use of Precedent of the Court of Justice of the European Union’. Comparative Political Studies 50 (7): 879–907. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414016639709.

Madsen, Mikael, and Urška Šadl. 2016. ‘A “Selfie” from Luxembourg: The Court of Justice and the Fabrication of the Pre-Accession Case-Law Dossiers’. Columbia Journal of European Law 22 (2): 327.

Menéndez, Agustín José. 2010. ‘European Citizenship after Martínez Sala and Baumbast: Has European Law Become More Human but Less Social?’ In The Past and Future of EU Law: The Classics of EU Law Revisited on the 50th Anniversary of the Rome Treaty, by Luis Miguel Poiares Pessoa Maduro and Loic Azoulai. Hart Publishing.

Minderhoud, Paul, and Sandra Mantu. 2017. ‘Back to the Roots? No Access to Social Assistance for Union Citizens Who Are Economically Inactive’. In Questioning EU Citizenship : Judges and the Limits of Free Movement and Solidarity in the EU, edited by Daniel Thym, 89–109. Modern Studies in European Law. Oxford: Hart Publishing.

NicShuibhne, Niamh. 2012. ‘(Some of) the Kids Are All Right’. Common Market Law Review 49 (Issue 1): 349–380. https://doi.org/10.54648/COLA2012011.

———. 2015. ‘Limits Rising, Duties Ascending: The Changing Legal Shape of Union Citizenship’. Common Market Law Review 52 (4): 889–937. https://doi.org/10.54648/cola2015074.

O’Brien, Charlotte. 2017. ‘The ECJ Sacrifices EU Citizenship in Vain: Commission v. United Kingdom’. Common Market Law Review 54 (1): 209–243. https://doi.org/10.54648/cola2017007.

O’Leary, Síofra. 1999. ‘Putting Flesh on the Bones of European Union Citizenship Court of Justice’. European Law Review 24: 68–79.

Panagis, Yannis, and Urška Šadl. 2015. ‘The Force of EU Case Law: A Multi-Dimensional Study of Case Citations’. Legal Knowledge and Information Systems, no. 279: 71–80. https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-609-5-71.

Reynolds, Stephanie. 2017. ‘(De)Constructing the Road to Brexit: Paving the Way to Further Limitations on Free Movement and Equal Treatment?’ In Questioning EU Citizenship : Judges and the Limits of Free Movement and Solidarity in the EU, edited by Daniel Thym. London: Hart Publishing.

Šadl, Urška. 2021. ‘Old Is New: The Transformative Effect of References to Settled Case Law in the Decisions of the European Court of Justice’. Common Market Law Review 58 (6): 1761–1788. https://doi.org/10.54648/COLA2021111.

Šadl, Urška, Lucía López Zurita, and Sebastiano Piccolo. 2023. ‘Route 66: Mutations of the Internal Market Explored through the Prism of Citation Networks’. International Journal of Constitutional Law 21 (3): 826–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/icon/moad063.

Šadl, Urška, and Mikael Rask Madsen. 2016. ‘Did the Financial Crisis Change European Citizenship Law? An Analysis of Citizenship Rights Adjudication before and after the Financial Crisis’. European Law Journal 22 (1): 40–60.

Šadl, Urška, and Henrik Palmer Olsen. 2017. ‘Can Quantitative Methods Complement Doctrinal Legal Studies? Using Citation Network and Corpus Linguistic Analysis to Understand International Courts’. Leiden Journal of International Law 30 (2): 327–349. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0922156517000085.

Šadl, Urška, and Suvi Sankari. 2017. ‘Why Did the Citizenship Jurisprudence Change?’ In Questioning EU Citizenship: Judges and the Limits of Free Movement and Solidarity in the EU, edited by Daniel Thym, 89–109. Modern Studies in European Law. Oxford: Hart Publishing.

Schmidt, Susanne K. 2017. ‘Extending Citizenship Rights and Losing It All: Brexit and the Perils of “Over-Constitutionalisation”’. In Questioning EU Citizenship : Judges and the Limits of Free Movement and Solidarity in the EU. Hart Publishing. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781509914678.

Shaw, Jo. 2010. ‘A View of the Citizenship Classics: Martínez Sala and Subsequent Cases on Citizenship of the Union’. In The Past and Future of EU Law: The Classics of EU Law Revisited on the 50th Anniversary of the Rome Treaty, by Luis Miguel Poiares Pessoa Maduro and Loic Azoulai. Hart Publishing.

Spaventa, Eleanor. 2017. ‘Earned Citizenship – Understanding Union Citizenship through Its Scope’. In EU Citizenship and Federalism, edited by Dimitry Kochenov, 1st ed., 204–225. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139680714.009.

Thym, Daniel. 2015. ‘The Elusive Limits of Solidarity: Residence Rights of and Social Benefits for Economically Inactive Union Citizens’. Common Market Law Review 52 (1): 17–50. https://doi.org/10.54648/cola2015002.

European University Institute, eftychia.constantinou@eui.eu, https://orcid.org/0009-0003-2565-1088.↩︎

European Commission, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions Establishing a European Pillar of Social Rights COM/2017/0250 final.↩︎

Joined cases C-424/10 and C-425/10 Ziolkowski and Szeja ECLI:EU:C:2011:866.↩︎

Case C-158/07 Förster ECLI:EU:C:2008:630.↩︎

Joined cases C-22/08 and C-23/08 Vatsouras and Koupatantze ECLI:EU:C:2009:344.↩︎

Case C-140/12 Brey ECLI:EU:C:2013:565.↩︎

Case C-333/13 Dano ECLI:EU:C:2014:2358.↩︎

Case C-67/14 Alimanovic ECLI:EU:C:2015:597.↩︎

Case C-299/14 García-Nieto ECLI:EU:C:2016:114.↩︎

Case C-85/96 Martínez Sala ECLI:EU:C:1998:217.↩︎

Case C-184/99 Grzelczyk ECLI:EU:C:2001:458.↩︎

Case C-224/98 D’Hoop ECLI:EU:C:2002:432.↩︎

Case C-413/99 Baumbast ECLI:EU:C:2002:493.↩︎

Case C-209/03 Bidar ECLI:EU:C:2005:169.↩︎

European Union, Directive 2004/38/EC of the European Parliament and the Council of 29 April 2004 on the right of citizens of the Union and their family members to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member States amending Regulation (EEC) No 1612/68 and repealing Directives 64/221/EEC, 68/360/EEC, 72/194/EEC, 73/148/EEC, 75/34/EEC, 75/35/EEC, 90/364/EEC, 90/365/EEC and 93/96/EEC, 29 April 2004, 2004/38/EC.↩︎

Case C-127/08 Metock ECLI:EU:C:2008:449.↩︎

Case C-109/01 Akrich ECLI:EU:C:2003:491.↩︎

Court of Justice of the European Union, “InfoCuria Case-law“ Accessed November 1, 2023 <https://curia.europa.eu/juris/recherche.jsf?cid=6359002> .↩︎

Gephi, Accessed November 1, 2023 <https://gephi.org/ >.↩︎

Case C-148/02 Garcia Avello ECLI:EU:C:2003:539.↩︎

Case C-406/04 De Cuyper ECLI:EU:C:2006:491.↩︎

The numbers inside the brackets display the in-degree score for each judgment.↩︎

Case C-165/14 Rendón Marín ECLI:EU:C:2016:675.↩︎

Case C-133/15 Chavez-Vilchez ECLI:EU:C:2017:354.↩︎

Case C-34/09 Ruiz Zambrano ECLI:EU:C:2011:124.↩︎

Case C-802/18 Caisse pour l'avenir des enfants ECLI:EU:C:2020:269.↩︎

Case C-22/18 TopFit and Biffi ECLI:EU:C:2019:497.↩︎

Case C-483/17 Tarola ECLI:EU:C:2019:309.↩︎

Case C-709/20 CG ECLI:EU:C:2021:602.↩︎

CG [65-66].↩︎

CG [93].↩︎

CG [62].↩︎

Dano [58].↩︎

TopFit and Biffi [28].↩︎

Case C‑411/20 Familienkasse ECLI:EU:C:2022:602.↩︎

Familienkasse [28].↩︎

CG [62].↩︎

Case C-181/19 Jobcenter Krefeld ECLI:EU:C:2020:794.↩︎

Jobcenter Krefeld [39].↩︎

Jobcenter Krefeld [68].↩︎

Jobcenter Krefeld [87].↩︎

Jobcenter Krefeld [35, 37, 48].↩︎

Brey [70].↩︎

Brey [72].↩︎

Council of the European Union, Regulation (EEC) No 1612/68 of the Council of 15 October 1968 on Freedom of Movement for Workers within the Community OJ L 257.↩︎

Martínez Sala [62-65].↩︎

Jobcenter Krefeld [67-71].↩︎

Jobcenter Krefeld [75].↩︎

Jobcenter Krefeld [75].↩︎

Jobcenter Krefeld [76].↩︎

Zambrano [42].↩︎

Case C-434/09 McCarthy ECLI:EU:C:2011:277.↩︎

Case C-256/11 Dereci and Others ECLI:EU:C:2011:734.↩︎

Chavez-Vilchez [72].↩︎

Rendón Marín [87].↩︎

Case C‑165/16 Lounes ECLI:EU:C:2017:862 [48].↩︎