Article History Submitted 1 February 2024. Accepted 26 April 2024. Keywords constitutional design, expert survey, empirical constitutional law |

Abstract National constitutions codify provisions on a wide range of topics, ranging from presidential term limits to the country’s flag. But are all constitutional provisions equally important? Some are likely to be particularly consequential for how governments function, while others are likely to be largely symbolic. To date, there has been little research on the relative importance of constitutional provisions. To explore current thinking on this subject, we assembled a group of twelve comparative constitutional scholars to rate the relative importance of 340 constitutional provisions to the functioning of a country’s government. These aggregate ratings make three contributions to constitutional studies: (1) provide evidence on the current state of academic thought on the comparative importance of constitutional provisions; (2) establish an index of constitutional importance to be used in future research projects; and (3) offer a roadmap that could help direct research to provisions that may be more likely to have significant impacts on governance-related outcomes. |

|---|

According to an old saying attributed to Mark Twain, an expert is “just an ordinary fellow from another town.” Constitution-making frequently attracts such fellows. When countries begin a process to draft new a constitution or amend an existing one, constitutional law experts from all over the world often converge to offer advice to the drafters (Aucoin 2004; Hudson 2021). The level of these experts’ involvement can range from giving presentations on foreign experiences, to outlining the pros and cons of different design choices, to offering specific recommendations on what design choices are best for the country, and even to drafting language that makes its way into the final text.

When weighing in on constitutional-drafting, these experts have been increasingly able to draw on a growing body of academic research on constitutional design.13 And while constitutional design research was once based on theoretical claims, normative arguments, and casual observations alone, a new field of empirical research has emerged studying consequences of constitutional design choices (e.g., Hirschl 2016; Elkins and Ginsburg 2021; Chilton and Versteeg 2022a). This field is producing empirical evidence on how the constitutional provisions that countries adopt influence a range of outcomes (e.g., Landau 2012; Chilton and Versteeg 2016, 2020; Voigt 2021; Lewkowicz and Lewzcuk 2023; Landau and Dixon 2020).

In addition to producing new substantive findings, this field is also generating a large amount of data on countries’ constitutions. The most comprehensive and prominent dataset on constitutional provisions—the Comparative Constitutions Project (“CCP”)—now includes over 1,200 variables on the features of over 800 national constitutions (Elkins, Melton, and Ginsburg 2009). Beyond the CCP, other datasets have coded other specific aspects of constitutions. For instance, there are now datasets that code the specific rights commitments included in constitutions (e.g., Law and Versteeg 2011); the processes countries used to draft their constitutions (e.g., Eisenstadt, LeVan, and Maboudi 2017); the presence of unwritten, small-c constitutional provisions (Chilton and Versteeg 2022b); the presence of civic duties within constitutions (Altan and Versteeg 2023); and the degree of compliance with constitutions (e.g., Gutmann, Metelska-Szaniawska, and Voigt 2023).

But despite this explosion of research and data on the world’s constitutions, many constitutional design questions still have very few answers. For example, what are the most important provisions to include in a constitution? Are some provisions more or less important for different kinds of nations? For several reasons, these questions currently do not have good answers. For one, the field is still new, and simply has not had time to examine the impact of many important design choices. Additionally, the effects of specific design choices may vary considerably depending on context, such that even for aspects of constitutions that have been heavily researched, the likely effect of choices made in specific settings remains largely unknown. Moreover, given the methodological challenges associated with researching constitutions, the rigorous study of the impact of even a single constitutional provision can take multiple papers, a range of research methods, and many years of research time. Thus, even as the field has thrived, many of the most fundamental questions about constitutional effectiveness remain either unexplored or only partially answered.

Because some of the most important questions in the field lack rigorous social scientific exploration, in many instances, scholars and policymakers are forced to rely on casual observations and their own intuition when making decisions about both research priorities and real-world constitutional design choices. Relatedly, quantitative researchers can choose from 1000+ variables on constitutions, and their decision to explore some, but not others, is likely guided by casual observation and intuition as well. Similar processes likely unfold when experts involve themselves in real-world constitution-making processes and constitution-makers debate what provisions to include in constitutions.

In this paper, we propose a method to help guide these intuitions by creating an index of collective intuition. The key idea underlying our proposal is that, while one expert might be misguided in their intuitions, it is less likely (though far from impossible) that all of them would be wrong—especially when each expert considers and evaluates separately.

Our research design for this project is simple. We assembled ourselves together as a group of twelve scholars who research and study constitutions and constitutional law around the world. We then each separately reviewed the 340 types of provisions that have previously been identified by Constitute as potentially being covered by current national constitutions (Elkins et al. 2014). For each of these provisions, we each rated how unimportant or important we believe it to be for the nature of a country’s government. When providing these assessments, we did so for countries in general as well as for three specific types of countries: functioning democracies, new democracies, and divided democracies (that is, democracies where identity-based social divisions are politically salient). While our effort by no means exhausts the full scope of possible inquiries into constitutional importance, our exercise can provide a blueprint for future projects that could follow our lead.

The exercise revealed that there are four provisions as most important; that is, representing the most high-stakes constitutional design choices for constitutional governance. They are provisions on: (1) the constitutional amendment procedure; (2) whether or not elections are conducted by secret ballot; (3) whether there is an electoral commission to oversee elections; and (4) how the executive branch is structured. Also particularly important are executive term limits, executive decree powers, whether sub-national units have law-making powers, whether legislation can be vetoed, the selection procedures for the justices of the constitutional court, whether the constitution establishes electoral districts, and the emergency clause.

In the remainder of this paper, we compile and analyze the data from the 12 expert assessments in four ways. First, we explore the extent to which the experts agreed on the importance of constitutional provisions. Our results reveal that the experts took notably different approaches to rating the importance of constitutional provisions, with some experts rating a higher share of provisions as important than others. Additionally, there were some provisions that were rated consistently across members of the group, and other provisions where there was notable disagreement. Notably, expert agreement is highest with respect to structural elements of the constitution and lowest with respect to substantive values such as principles, symbols, rights, and duties.

Second, we explore the average ratings across constitutional provisions. Here, we note that the distribution of expert responses skews to the right, meaning experts’ general stance is that most provisions are considered at least somewhat important, and only very few are considered unimportant. More specifically, 87 out of 340 provisions received a mean score of 4.0 (somewhat important) or higher out of 5.0, and 245 provisions had a mean rating of higher than 3.0, which means they were considered to be more important than neutral. Only 11 out of the 340 provisions were rated as 2.0 (somewhat unimportant) or lower. Of the provisions that the experts deem most important, nearly all concern fundamental features of how to organize the government, and not rights, duties, or other values.

Third, we use the ratings to create an index of “Core Constitutional Provisions.” Although many different kinds of indexes could be created using our rating data—and we encourage and welcome other scholars to create them—we focus on building a simple index of the provisions that our group rated to be somewhat important or important (e.g., 4.0 or higher on our 5.0 scale). We then document the prevalence of these constitutional provisions across countries and over time. Our hope is that this index can help guide future empirical research on comparative constitutional law.

Fourth, we explore how our ratings depend on context by reporting differences in the ratings for different types of democracies: functioning democracies, new democracies, and divided democracies. We find that these differences, at least in the context of our study, are relatively small: most experts only make small changes and for only some provisions. Notably, experts believe that some design choices are more important for new and divided democracies than for functioning democracies or for all countries in general. Specifically, for the general category, 25.6 percent of constitutional provisions had a mean of 4.0 or higher. This figure was identical for functioning democracies. However, the share of provisions with a mean of 4.0 or higher was 33.8 percent for new democracies and 33.5 percent for divided democracies. This suggests that members of our group believed more aspects of constitutional design are important when democracies are fledgling or unstable than when they are already secure.

Before continuing, it is important to acknowledge several limitations of our results. To begin, we are a group of scholars with relatively similar backgrounds and research interests, and we live and work in a small number of countries. It is thus very possible that a different group of scholars would have produced different ratings. Moreover, we filled out this survey in a particular moment in time (fall 2023), and it is possible that our own views would be different at other moments in time. Finally, we acknowledge we may be collectively completely wrong about which constitutional provisions are important. Ours is not a study of cause and effect and we do not attempt to corroborate our intuitions in this project. Notably, we do not suggest that this kind of project is capable of definitively identifying which constitutional provisions are actually the most important. Instead, our hope is that this project can help provide a broader and richer intuitive framework for constitutional scholars and some insight into the perspective of a sizeable group of researchers on the current state of academic knowledge in a complex area of the law.

To evaluate which constitutional provisions are most important, we assembled a group of twelve experts with different methodological backgrounds and different areas of regional focus. Some of us work in the more quantitative social-science tradition while others do qualitative work, some of us work in comparative constitutional law while others work in comparative constitutional studies; some of us focus on one of these approaches while any of us combine them; and some of us have advised processes drafting constitutions or constitutional reforms or evaluating constitutional performance. But one thing the members of the group have in common is that all of us have spent years researching national constitutions around the world.

Each member of the group was asked to evaluate the importance of a comprehensive list of provisions that are sometimes included in national constitutions. We specifically used a taxonomy of constitutional topics created for Constitute (www.constituteproject.org), which was developed by the Comparative Constitutions Project to provide an easy way for people to read and compare the world’s constitutions (see Elkins et al. 2014). This taxonomy identified twelve categories of constitutional provisions. Those twelve categories include, for example, areas like Rights and Duties, Culture and Identity, and Federalism. Across those twelve categories, the taxonomy identified a total of 340 provisions. For example, within the Rights and Duties category, there are provisions related to the right to jury trials, the right to petition, or prohibition on torture. Importantly, not all constitutions include all 340 provisions. Instead, this taxonomy offers a list of provisions that national constitutions sometimes cover.

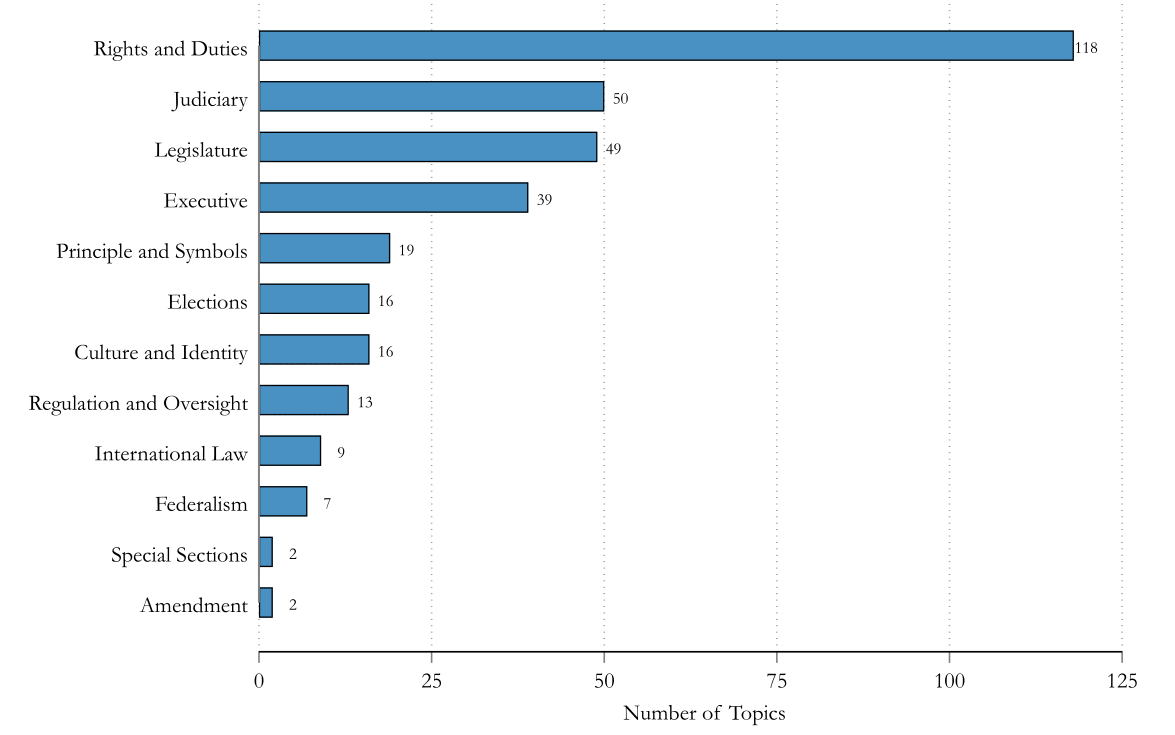

To illustrate this data, Figure 1 reports the number of constitutional provisions in each of the twelve categories. As Figure 1 reveals, there are large differences in the number of provisions within each category. For instance, the category with the most constitutional provisions is Rights and Duties (which has 118 constitutional provisions), and the categories with the fewest related constitutional provisions are Amendment and Special Sections (which both have two constitutional provisions).14 Or, put another way, 35 percent of provisions (118 out of 340) are related to the broad category of Rights and Duties, but less than 1 percent of provisions (2 out of 340) are related to the broad category of Amendment.

Figure 1. Number of Constitutional Provisions in Each Category. This figure reports the number of provisions by identified category. These classifications are from the Comparative Constitution Project.

For each of these 340 provisions, each member of our group answered the following question: “How important is this topic?” The prompt, which the group designed together prior to viewing the full list of provisions, further clarified that, “[b]y important, we mean that the stakes in what choice to make on this topic are high, because it has important implications for the nature of government in the country.” It also explained that the task is not to evaluate what the “best” choice is for governance, but rather “whether whatever choice is made has important implications for governance.” This means that the members of the group set to evaluate, for example, whether the choice on the constitutional amendment clause is important for constitutional governance (that is, how the country actually governs itself), not whether constitutions should be easy or hard to amend.

The members of the group answered this question four times for each of the 340 provisions. Each of those four times was designed to reflect whether the importance of different provisions may depend on context. While there are potentially endless configurations of relevant country characteristics, we decided to focus on four scenarios: (1) countries in general; (2) functioning democracies; (3) new democracies; and (4) divided democracies. We focused on democracies, in addition to countries in general, for two reasons. First, evidence suggests that higher-order laws are more likely to influence the behavior of democracies than autocracies (e.g., Simmons 2009; Ginsburg 2022; Gutmann, Metelska-Szaniawska, and Voigt 2023). Second and more normatively, we are more interested in understanding which constitutional design choices are important for constitutional drafting processes that strive towards democracy, rather than those focused on goals like extending presidential term limits to help shore up the power of autocratic leaders.

The four country prompts were designed as follows:

Countries in General. Without knowing much about the country, how important do you think this topic will be for the nature of governance?

Functioning Democracies. Now, imagine a functioning democracy. How important do you think this topic will be for the nature of governance? For the purpose of this exercise, we define a functioning democracy as follows, based on Jeremy Waldron (2006, 1360):

(1) democratic institutions in reasonably good working order, including a representative legislature elected on the basis of universal adult suffrage;

(2) a set of judicial institutions, again in reasonably good order, set up on a nonrepresentative basis to hear individual lawsuits, settle disputes, and uphold the rule of law;

(3) a commitment on the part of most members of the society and most of its officials to the idea of individual and minority rights; and

(4) persisting, substantial, and good faith disagreement about rights (i.e., about what the commitment to rights actually amounts to and what its implications are) among the members of the society who are committed to the idea of rights.

New Democracies. Now, imagine a new democracy. How important do you think this topic will be for the nature of governance? For the purpose of this exercise, we ask you to imagine a country transitioning away from dictatorship and with a commitment to become a democracy and to protect human rights. This country is writing a new constitution, but no elections have been held yet. In terms of the Waldron definition, we can say that there is a commitment to human rights (3) along with good-faith disagreements on their meaning (4). But there are no democratic institutions or strong courts yet.

Divided Democracies. Now, imagine a divided democracy. How important do you think this topic will be for the nature of governance? For the purpose of this exercise, we ask you to imagine society with identity-based social divisions (whether race, religion, ethnicity, or other) that are politically salient, so social cleavages serve as the basis for political alliances, mobilization, and policymaking. As Choudhry (2008, 5) puts it, in a divided society, “[e]thnocultural diversity translates into political fragmentation.... [such that] political claims are refracted through the lens of ethnic identity, and political conflict is synonymous with conflict among ethnocultural groups.” We are asking you to imagine a divided society that seeks to be a democracy, not a true autocracy. But at the same time, we note that in a divided society, democratic institutions cannot be taken for granted. The reason is that there is, as Guelke (2012, 32) puts it, “a lack of consensus on the framework for the making of decisions” as a result of which “the legitimacy of outcomes is commonly challenged by political representatives of one of the segments.”

After each of these four prompts, the members of the group were asked to evaluate the importance of each of the 340 provisions on a five-point scale that included: “Very Unimportant”, “Somewhat Unimportant”, “Neutral”, “Somewhat Important”, and “Very Important.” The order of the provisions was fixed per section. After assembling the ratings of all the experts into a single dataset, we then converted all responses from a categorical scale to a numerical scale ranging from 1 (very unimportant) to 5 (very important). The Online Appendix reports the complete mean responses, median responses, and the standard deviations for the four different prompts.15 We now turn to analyzing those results.

Before we explore which provisions were rated as being relatively more important, we start our analysis by exploring the extent to which there is inter-rater agreement on the level of importance of the constitutional provisions. We do so in two ways: (1) plotting the distribution of responses at the respondent level and (2) reporting the distribution of standard deviations of responses at the provision level.

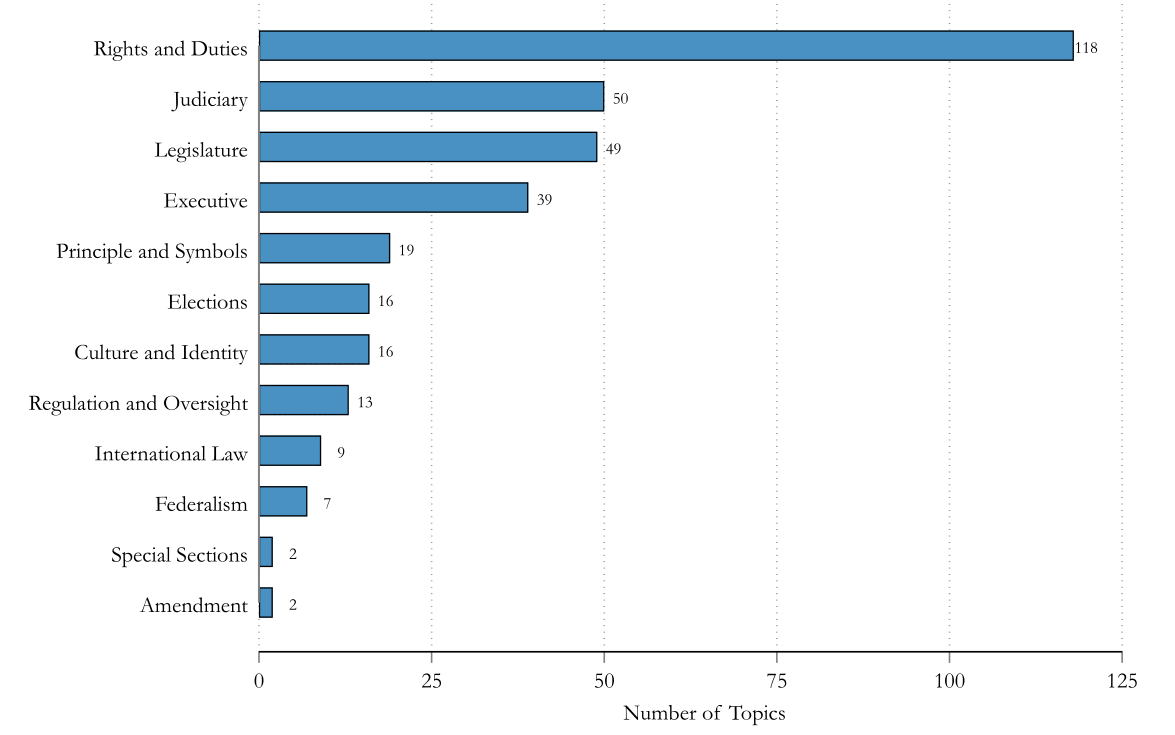

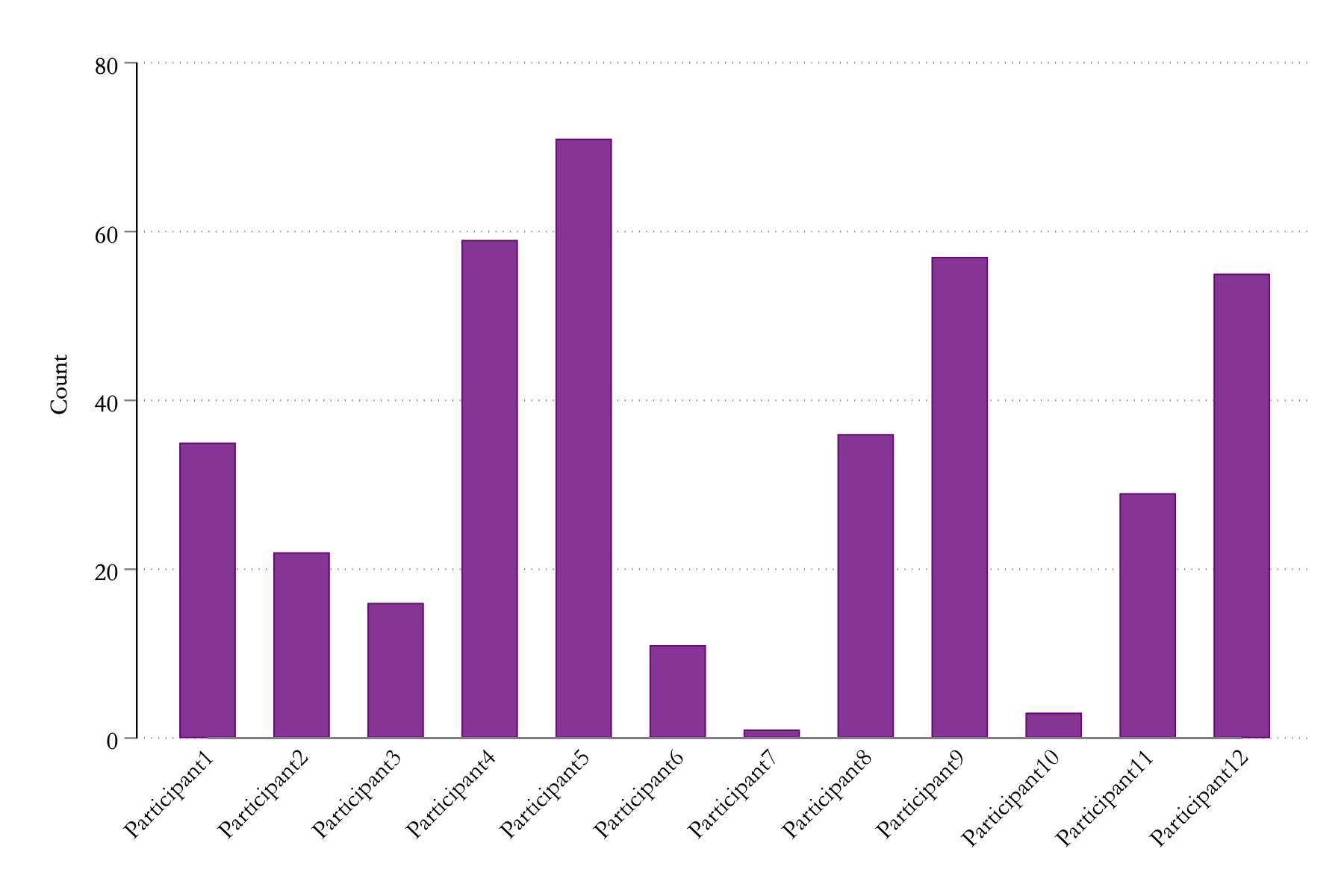

First, Figure 2 reports the distribution of the answers from each of the twelve experts for the general country prompt. It reveals notable differences in the distributions of responses. For instance, the ratings for some experts (Figure 2, Expert No. 1 and No. 2) are roughly uniformly distributed, with a similar numbers of provisions receiving each rating; the ratings for some participants (Figure 2, Expert No. 3 to No. 6) are roughly normally distributed, with ratings centered around neutral; and the ratings for some participants (Figure 2, Expert No. 7 to No. 12) are skewed to the right, with a notably higher number of provisions being rated as important than unimportant.

These initial results thus reveal that the experts did not take a single approach to assessing the importance of constitutional provisions. For instance, one expert prioritized institutional rules that shape elections, key institutions, and the separation of powers, given their importance for the emergence and maintenance of democracy. This approach produced a roughly uniform distribution. Another expert prioritized a broader set of provisions that structure the exercise of power in fundamental ways—including decisions that shape the structure of politics (such as federalism), those that concentrate or balance of power (such as term limits), and those that could protect the regime (such as electoral commissions)—while discounting rights and symbolic provisions. This approach produced a normal distribution.

One expert with a right-skewed distribution started all provisions at a default rating of ‘neutral,’ increasing the rating of provisions that structure governing institutions like the executive, legislature, and supreme court, and decreasing the rating of symbolic provisions that do not shape institutions. Another expert with a right-skewed distribution set different types of provisions at different starting scores, rating provisions that directly shape institutions’ structure and people’s ability to participate in the system as ‘very important,’ provisions that do the same indirectly as ‘somewhat important,’ institutional features and rights that don’t impact governance as ‘neutral,’ and symbolic provisions as unimportant. Critically, even though experts’ approaches and rating distributions are not identical, it does not mean that there is not some degree of agreement on the importance of different provisions. We thus also more formally assess our degree of inter-rater agreement.

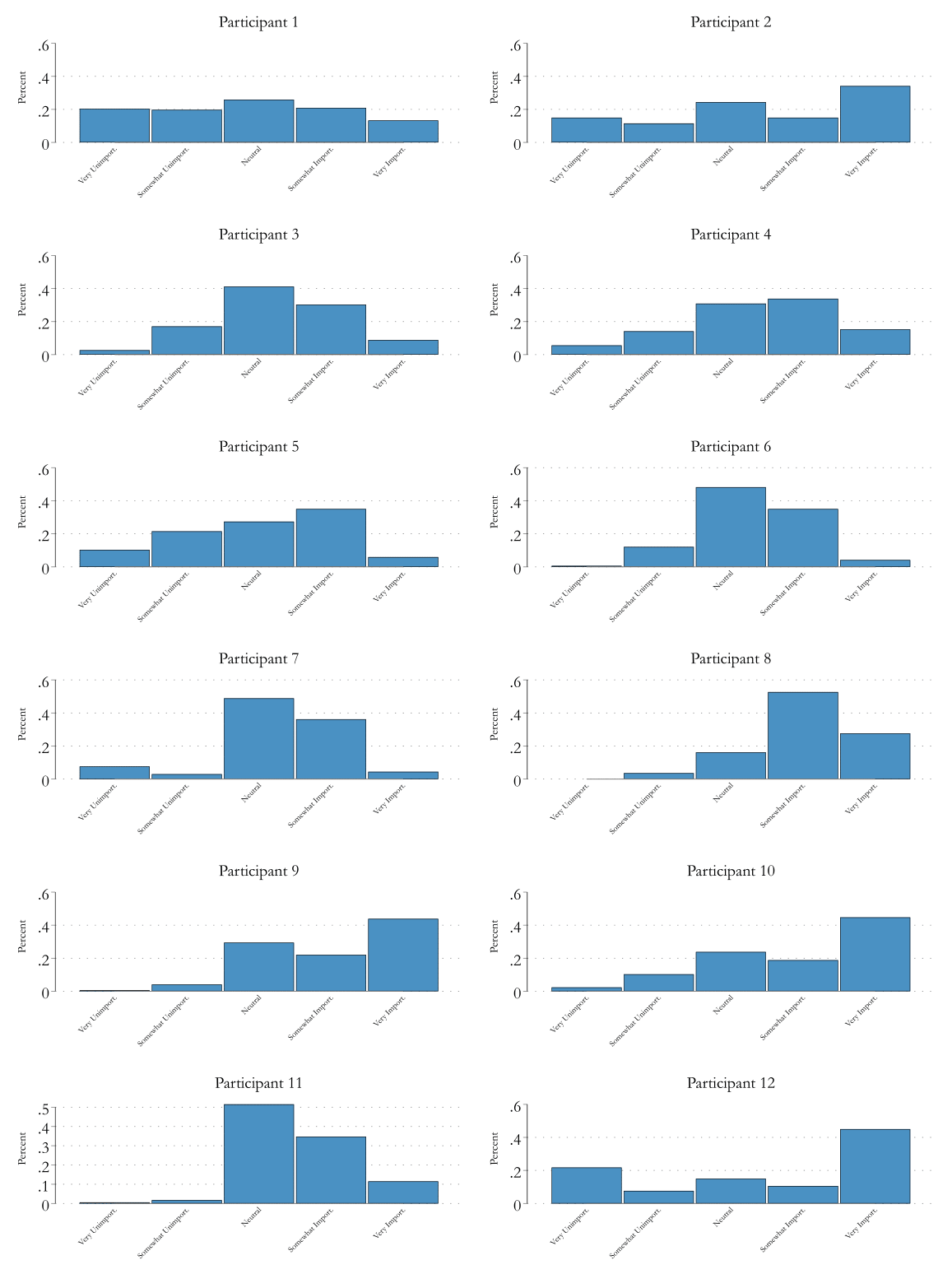

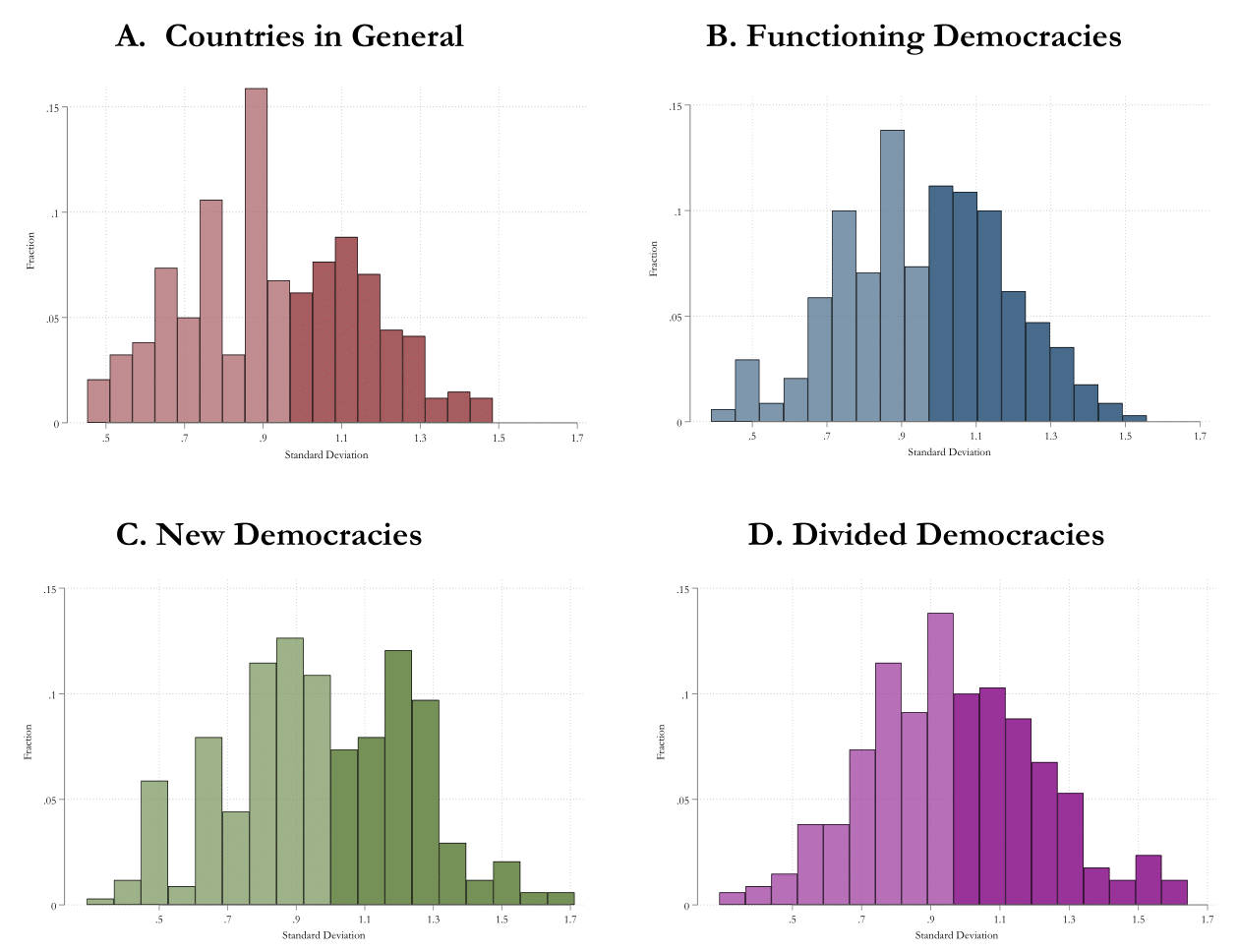

Second, we assess the inter-rater agreement in our responses by calculating the standard deviations in responses. Figure 3 reports the distribution of standard deviations for each of the 340 provisions separately for each of the four prompts. For each of the four prompts, the figure reveals that the distributions of standard deviations are roughly normally distributed around 1.0, with a range for the different provisions and contexts from roughly 0.28 to 1.7. The mean standard deviation is 0.93 for countries in general, 0.97 for functioning democracies, 0.97 for new democracies, and 0.96 for divided democracies.

Figure 2. Distribution of Answers by Expert. This figure reports the distribution of the answers given in the survey across 12 experts for “Countries in General”, with constitutional provisions coded from “Very Unimportant” to “Very Important”.

Figure 3. Distribution of the Standard Deviation by Provision. This figure reports the distribution of the standard deviations of the survey responses for all variables across all survey respondents, by provision. The results can be interpreted as the distribution of the level of agreement among survey respondents. Scores have been encoded to 1- 5 from categories “Very Unimportant”, “Somewhat Unimportant”, “Neutral”, “Somewhat Important”, and “Very Important”. Lighter bars correspond to lower variability (standard deviation < 1) and darker bars correspond to higher variability (standard deviation > 1).

To put the results in Figure 3 in context, one of the provisions tied for the lowest standard deviation for countries in general is the use of secret ballots in elections, which has a standard deviation of 0.45 for countries in general. For this provision, three experts scored it as a “Somewhat Important”, and nine experts scored it as a “Very Important”. One of the provisions tied for having a standard deviation closest to the mean for countries in general is equality regardless of sexual orientation, which has a standard deviation of 0.94. For this provision, three experts scored it as a “Very Important”, six scored it as a “Somewhat Important”, and three scored it as a “Neutral”. And the provision with the highest standard deviation for countries in general is the existence of preferred political parties, which has a standard deviation of 1.48. For this provision, five experts scored it as “Very Important”, three scored it as “Somewhat Important”, two scored it as “Neutral”, and two scored it as a “Very Unimportant”.

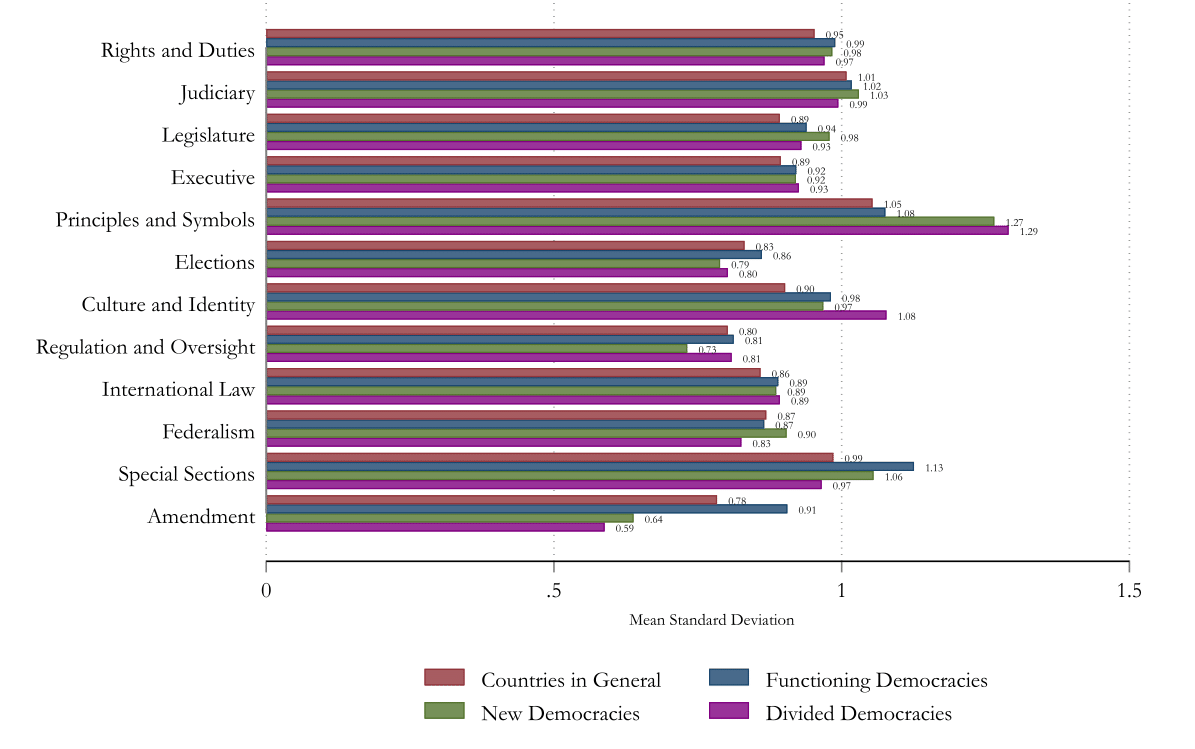

Thus far, we have illustrated the level of agreement across all provisions for a given prompt. However, it is possible that there are certain kinds of provisions where there are systematically higher levels of agreement than others. To probe this, Figure 4 recreates the analyses from Figure 3, but it does so separately for each of the twelve categories of constitutional provisions from the Constitute taxonomy that were shown in Figure 1. It shows that, for countries in general, the average standard deviations range from 1.05 for the Principles and Symbols category to 0.78 for the Amendment category. The low and high agreement in these areas becomes even more pronounced when experts considered the importance of these provisions for new and divided democracies. The average standard deviations for provisions related to Principles and Symbols increase to 1.27 and 1.29 for new and divided democracies and decrease to 0.64 and 0.59 for provisions related to Amendment. Namely, the consensus regarding the importance of Amendment provisions was higher for new and divided democracies, but opinions varied more with respect to the importance of Principles and Symbols for these regimes.

Figure 4. Standard Deviation by Category. The figure reports the mean standard deviation of responses across categories of constitutional provisions. The categories of provisions are ordered to reflect the order of the categories as presented in Figure 1.

Notably, Figure 4 shows that the categories that are most contested among the experts are Principles and Symbols, Special Sections, Rights and Duties, and the Judiciary. Three of these four categories—Principles and Symbols, Special Sections, and Rights and Duties—do not concern the structure of government, but rather concern the substantive values enshrined in the constitution. It appears, then, that experts stand more divided in their evaluation of values than structure. The fourth category—the Judiciary—does concern the structure of government, but it is noteworthy that the literature stands divided over the extent to which courts are able to protect democracy or rights (compare, e.g., Issacharoff 2015 with Chilton and Versteeg 2018; Daley 2017).

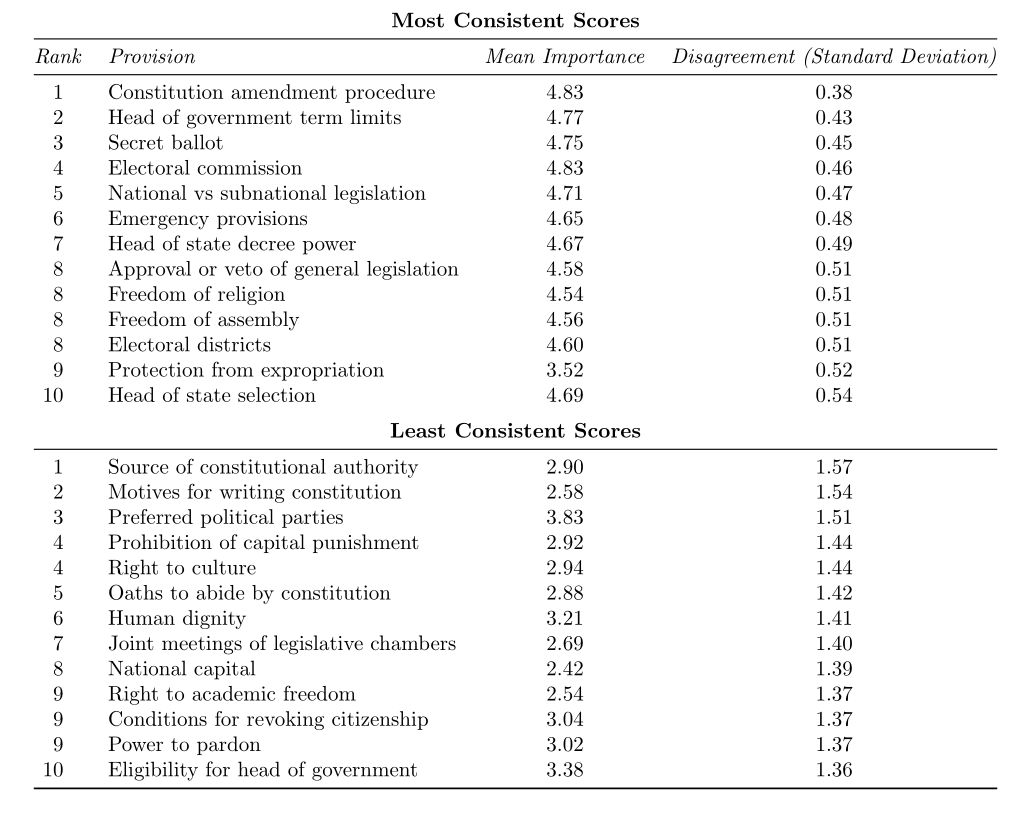

To probe these results further, Table 1 reports the 10 provisions with the lowest standard deviations and the 10 provisions with the highest standard deviations. To produce the list reported in Table 1, we average the means and standard deviations across the four ratings (i.e., countries in general, functioning democracies, new democracies, and divided democracies). The results reveal that many of the provisions with the lowest standard deviations, like amendment procedures and term limits for the head of government, are also provisions with high levels of importance (a provision we will explore more in the next section). Importantly, then, even with the diverse frameworks experts used for prioritizing provisions, there is strong agreement on the most important constitutional provisions. Table 1 also reveals that the provisions with the highest standard deviations are diverse. For instance, the provisions with the most disagreement between the members of the group were on the source of constitutional authority, preferred political parties, and the motives for writing the constitutions.

Table 1. Constitution Provisions by Standard Deviation. This table reports the ten constitutional provisions with the lowest standard deviations and the ten constitutional provisions with the highest standard deviations in the responses for the twelve members of the group rating them.

We next turn to reporting the average importance ratings that the experts provided for the constitutional provisions. In this part, we report the average importance ratings for countries in general, and in Part 6 we report these results for the three different kinds of democracies.

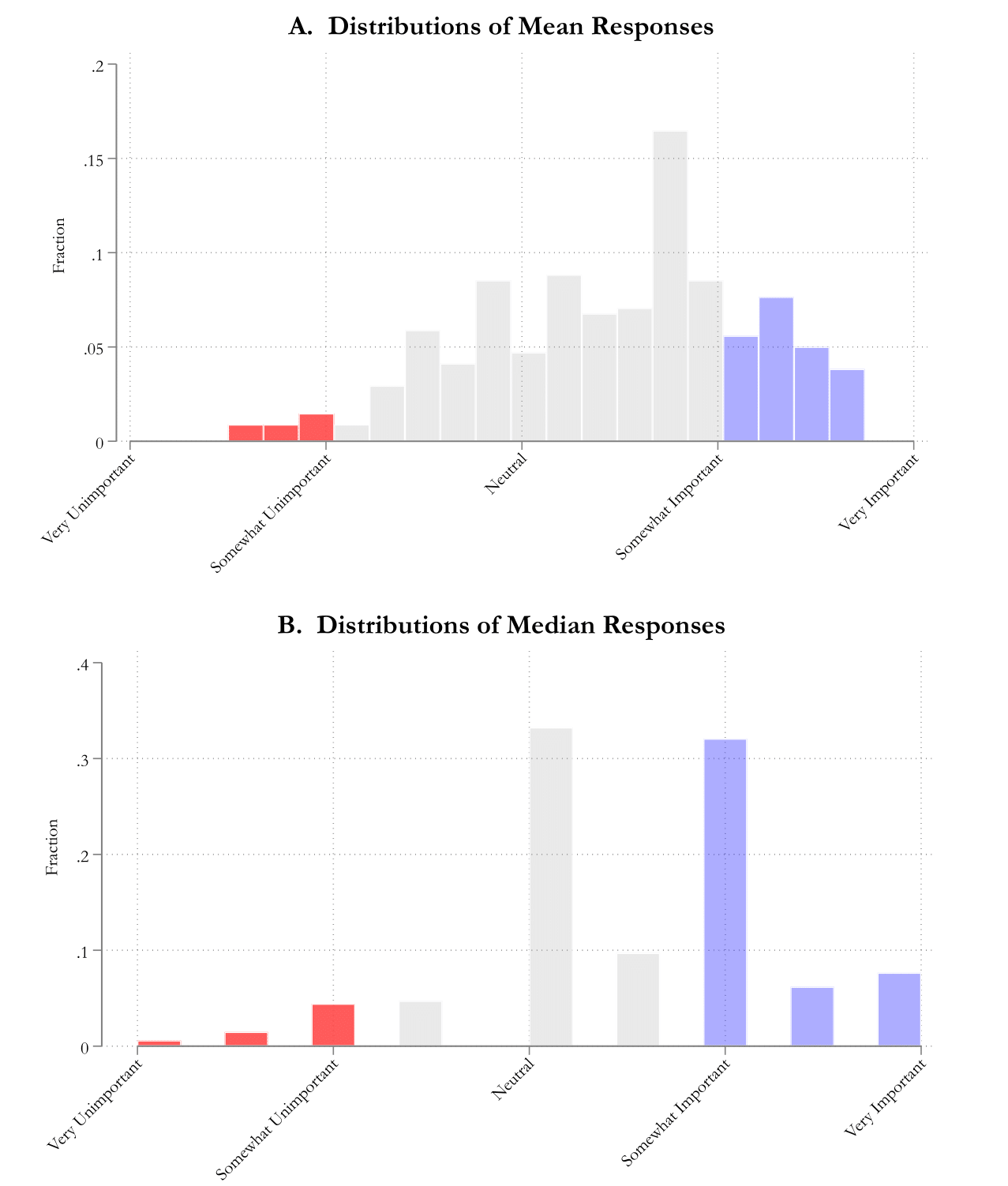

To begin, Figure 5 reports the distribution of the average ratings of the 340 constitutional provisions when we each evaluated them for countries in general. Panel A of Figure 5 reports the distribution of mean ratings at the provision level. The distribution reveals that a majority of the constitutional provisions were rated as being more important than unimportant. More specifically, 72 percent of the constitutional provisions (245 out of 340) had a mean rating higher than 3.0 on our 5-point scale. On the right end of the distribution, 22 percent of the constitutional provisions (75 out of 340) had a mean rating of 4.0 or higher. In other words, roughly a quarter of the constitutional provisions were rated by the experts as being somewhat or very important on average. On the other end of the distribution, just 3 percent of the constitutional provisions (11 out of 340) had a mean rating of 2.0 or lower, revealing that very few provisions were rated as being unimportant by the experts. Perhaps this finding is unsurprising. The survey did not include topics that do not appear in a single constitution, even though there is a lot of variation in how common the different topics are in actual constitutions. But when (at least some) constitution- makers go through the trouble of including topics, it is perhaps unsurprising that experts’ general posture is to not dismiss them as unimportant.

Figure 5. Constitution Provisions by Standard Deviation. This table reports the ten constitutional provisions with the lowest standard deviations and the ten constitutional provisions with the highest standard deviations in the responses for the twelve members of the group rating them.

Panel B of Figure 5 reports the distribution of median ratings at the provision level. The distribution reveals that the plurality median rating was “neutral”. More specifically, 33 percent of constitutional provisions (113 of 340) received a median rating of 3.0 on our five-point scale. On the right end of the distribution, 46 percent of the constitutional provisions (156 out of 340) had a median rating of 4.0 or higher. On the other end of the distribution, 6 percent of constitutional provisions (22 out of 340) had a median rating of 2.0 or lower. Taken together, the results in Panel B of Figure 5 reveal that a larger share of constitutional provisions have an average rating of either important or unimportant when using the median as the measure of central tendency as opposed to the mean.

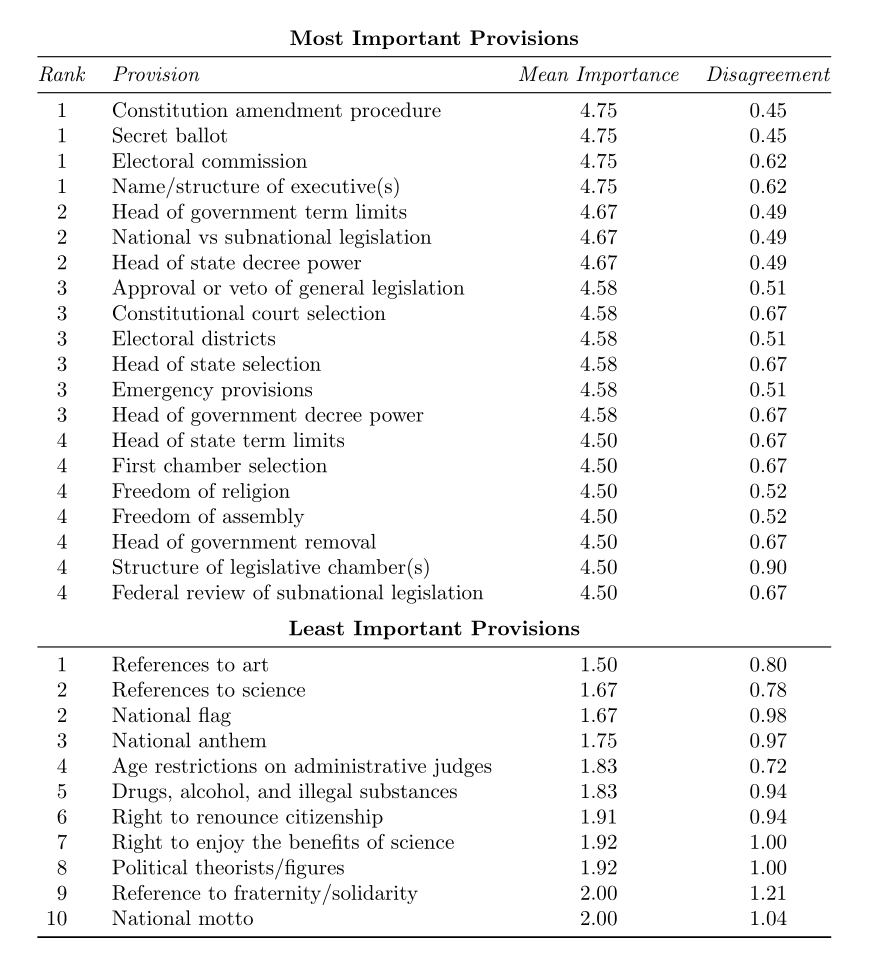

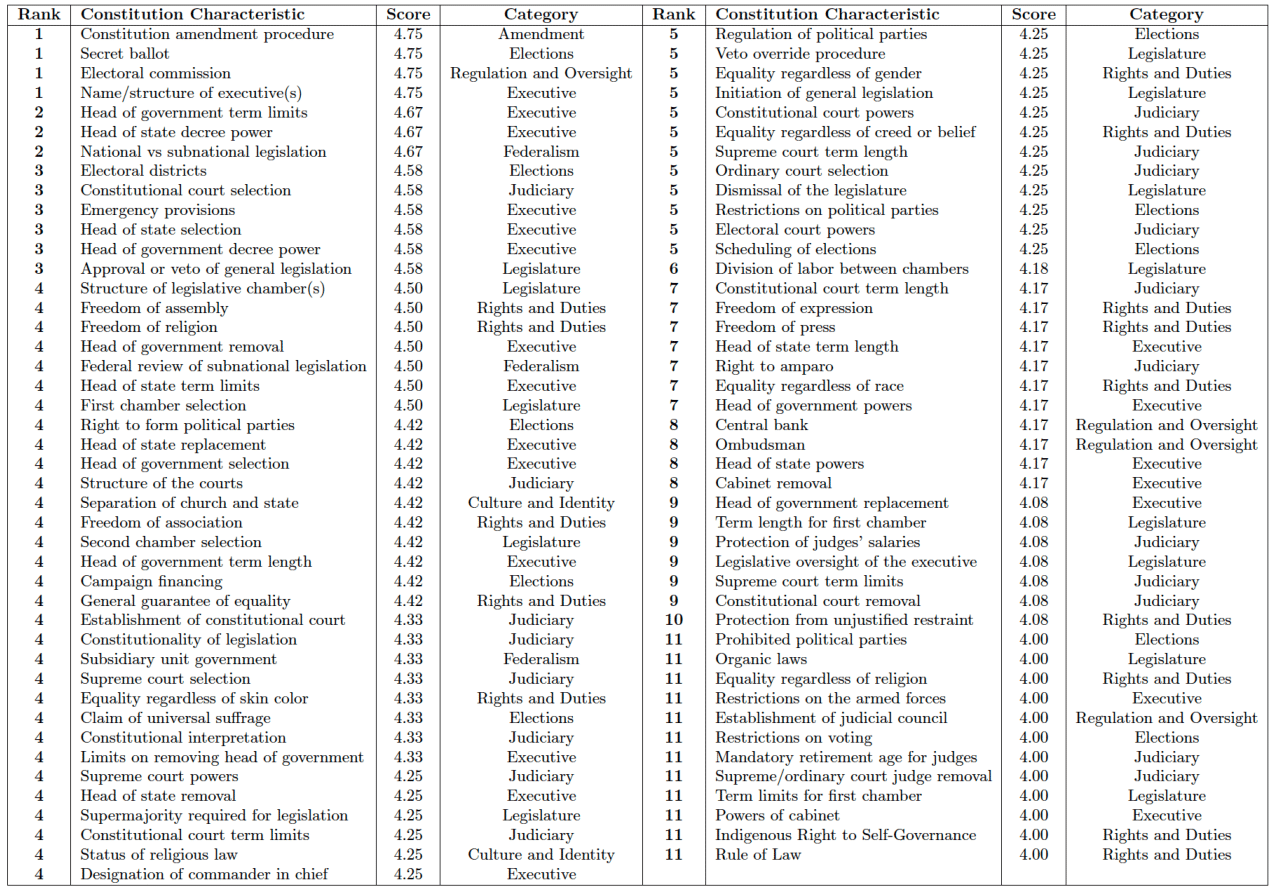

To further explore these ratings of the importance of constitutional provisions, Table 2 presents the top 10 most and least important provisions (as well as ties), based on their mean ratings. For the list of the top 10 most important provisions, each of the 10 had a mean rating of 4.5 or higher on the five-point scale. On this list, four provisions with average ratings of 4.75 are tied for being deemed as the most important. One of them is an electoral commission that can manage and oversee the country’s elections. Notably, this is an increasingly common design feature that is also correlated with higher levels of de facto democracy (Ginsburg and Versteeg 2023). Another of them is the constitution’s amendment procedure. This is perhaps unsurprising given that the amendment procedure within a constitution has important implications for constitutional governance more broadly (Albert 2019). Where constitutions are malleable, courts become relatively less important in determining the constitution’s meaning (Versteeg and Zackin 2016), though it has been shown that informal amendment by judicial interpretation can occur also where constitutions are relatively easy to amend (Besso 2005). Where the constitution is difficult to amend, constitutional meaning changes primarily through judicial interpretations (Albert 2014), and interpretative approaches like originalism become relatively more important (e.g., Tew 2017). Constitutional amendment, then, is one of the most high-stakes provisions in constitution-making, according to the experts. 16

Also in the list of the top 10 most important provisions are term limits on the head of government, federalism, the way the executive is structured, secrecy of ballots, selection of the head of state, how judges on the constitutional court are selected, decree powers for the executive, and veto powers for the executive. It is easy to see these provisions as representing some of the most foundational design choices constitution-makers must make: whether and what kind of a democracy the country aspires to be. By contrast, as the list of the top 10 least important provisions reveals, the provisions that were deemed the least important for constitutional governance concern symbolic values—like references to the art, references to science, and provisions on drugs, alcohol, and illegal substances. Also included in the list of least important provisions are constitutional provisions related to the flag and the national anthem. Notably, many of these provisions neither structure government in important ways nor place obligations upon the government. They are therefore more aspirational or symbolic in character. But it is worth noting that, on average, these provisions still received average ratings closer to “somewhat unimportant” than “very unimportant.”

Rights and duties, despite being the largest category in the CCP index, with 118 provisions, placed relatively few provisions at the top ranks of importance. Political rights ranked highest, led by freedom of assembly and religion (at the 15th and 16th places), followed by the right to form political parties and freedom of association. A general guarantee of equality is ranked next, followed by specific guarantees of equality regardless of skin color and gender.

Table 2. Most and Least Important Characteristics. Constitution Provisions by Standard Deviation. This table reports the 10 constitutional provisions with the highest mean score attributed by the experts, as well as the 10 constitutional provisions with the lowest mean scores across all questions. Disagreement is measured by the standard deviation. Scores have been encoded to 1-5 from categories “Very Unimportant”, “Somewhat Unimportant”, “Neutral”, “Somewhat Important”, and “Very Important”.

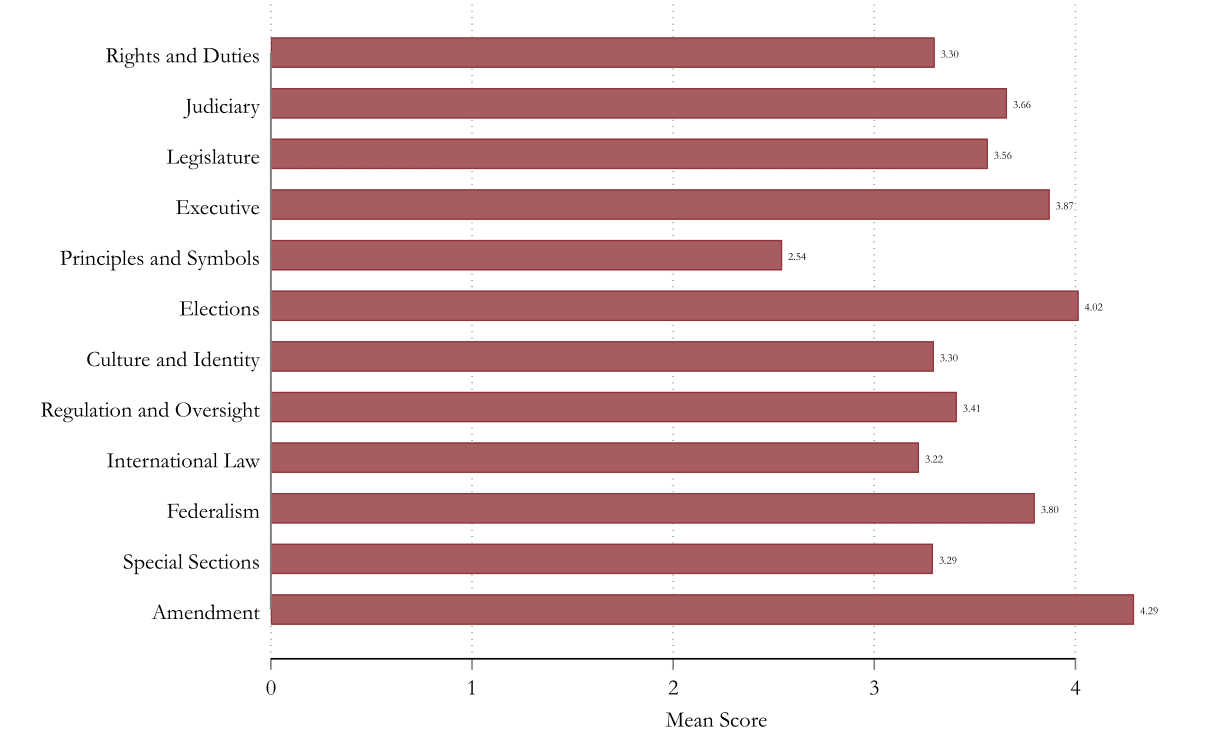

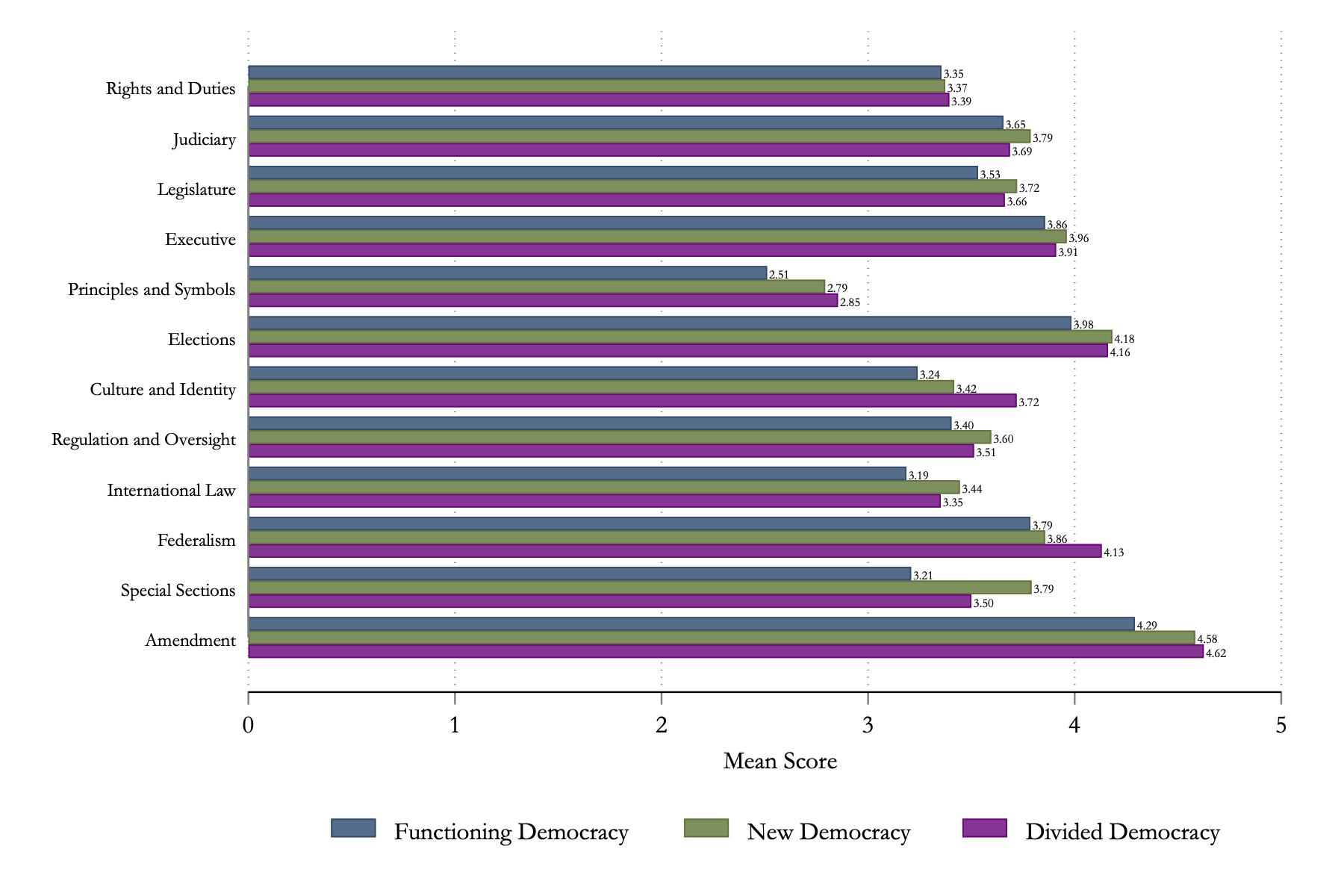

We next break present the results by category of provision. Figure 6 shows the mean score across the provisions for each of the twelve categories. It reveals that the category of provisions with the highest average rating relates to Amendment procedures. Although just two provisions are grouped into this category, those two provisions have an average rating of 4.29. The categories of provisions with the next highest average ratings relate to Elections (with a 4.02 average rating across provisions) and the Executive (with a 3.79 average rating across provisions). In contrast, the category of provisions with the lowest average rating relates to Principles and Symbols (with a 2.54 average rating across provisions), followed by International Law (with a 3.22 average rating across provisions) and Culture and Identity (with a 3.30 average rating across provisions). Taken together, consistent with the results in Table 2, Figure 6 reveals that the experts believe that provisions related to constitutional reform and elections are the most important provisions and that provisions related to substantive values are the least important provisions.

Figure 6. Mean Importance by Category. This figure reports average rating scores attributed by survey respondents grouped by category for countries in general.

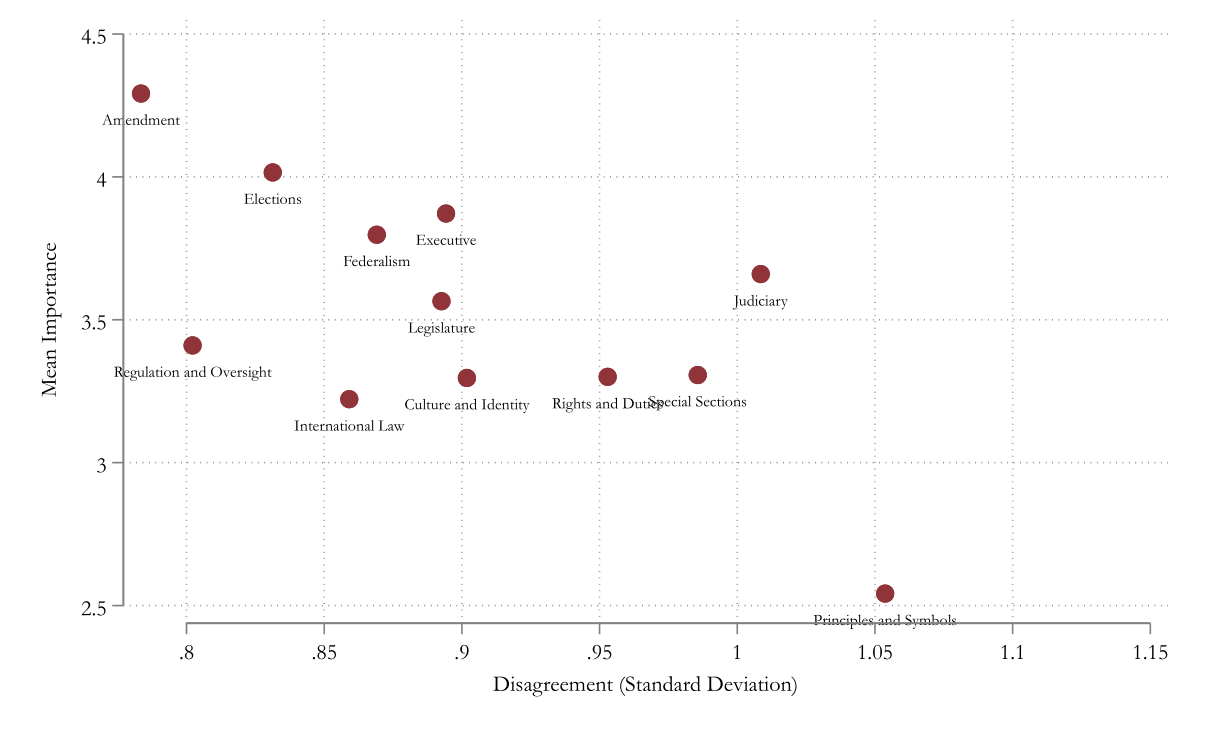

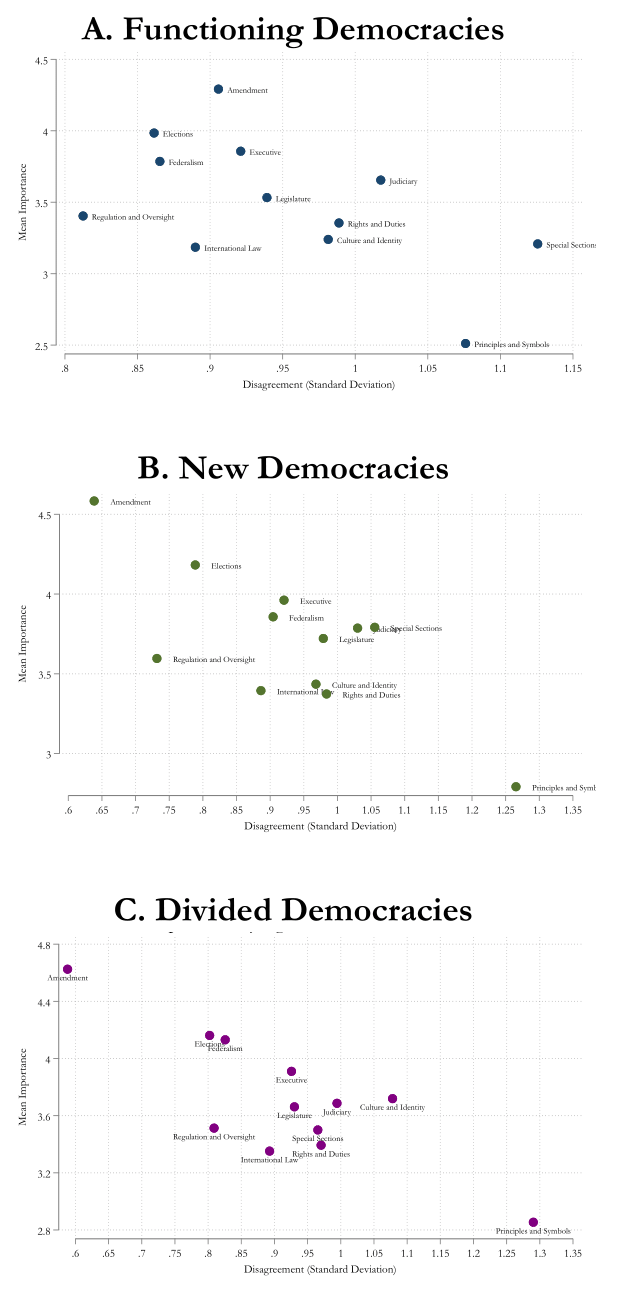

Finally, Figure 7 explores the relationship between the categories’ average levels of disagreement (as measured by the average standard deviations for that category) and their average levels of importance. It reveals a negative relationship, such that the categories with lower levels of disagreement generally also have higher levels of average mean importance. For instance, the category of provisions related to amendment procedures has both the lowest average standard deviation and the highest mean importance scores. In contrast, the provision related to Principles and Symbols has the highest average standard deviations and the lowest average mean importance scores. Thus, the non-structural parts of the constitution receive an average rating that is lower, but it also reflects disagreement among the experts on the extent to which these value-related parts are important.

Figure 7. Provision Importance and Agreement by Category. This figure reports the relationship between mean importance and mean standard deviation, grouped at the category level for countries in general.

Based on the mean results in the last section, it is possible to construct a “Core Constitutional Provisions Index”. We do so because such an index could be especially helpful to large-N researchers. Large-N scholarship often requires a reduced set of variables for a variety of exercises. In the case of constitutional studies, a great deal of empirical research focuses on making comparisons of constitutions both across countries and within countries. For instance, a standard kind of research project comparing constitutions across countries may be something along the lines of “do democracies have more similar constitutions to each other than autocracies have to each other.” Or “do countries that rewrite their constitutions make more changes when using certain kinds of reform processes than others?” Such exercises may be better conducted using only core variables, and not a list of 1000+ variables that may include highly idiosyncratic topics. Notably, including the more idiosyncratic features would produce artificially high similarity if most countries do, or do not, have these features.

For example, Bradford et al. (2019b) introduce a dataset coding countries’ competition laws over time. Their coding included a wide range of variables, however, so Bradford and Chilton (2018) also released an index of 36 “core” variables that they argued may paint a picture of the key features of country’s competition law regimes. In their case, they selected these variables based on their own substantive knowledge. In contrast, our survey makes it possible to construct this kind of index based the responses of a group of experts offering these ratings independently.

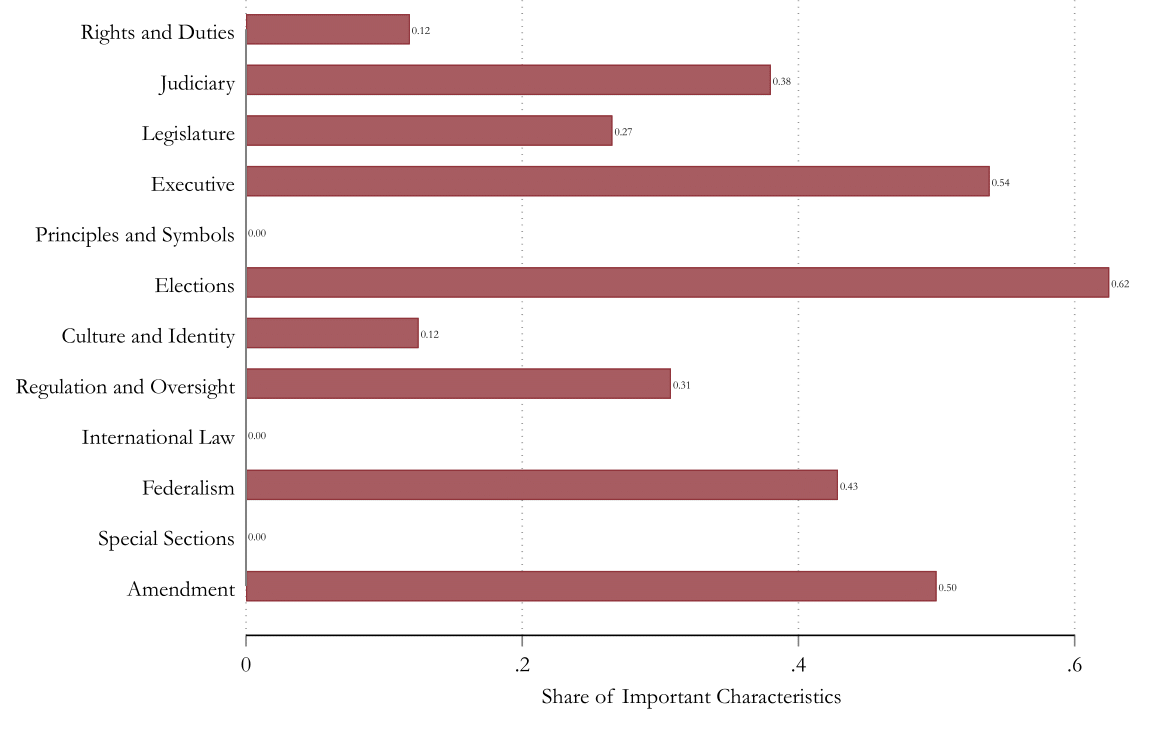

Using our survey results, there are many possible ways to construct such an index, and any of them are inherently somewhat arbitrary. For our purposes, we simply identify all provisions that received a score of 4.0 or higher (indicating a mean response that the provision was at least “somewhat important”). Of the 340 provisions, 87 achieved this score. These 87 provisions are listed in Table 3. To explore these provisions further, Figure 8 reports the share of the provisions in each category from Figure 1 that received a score of 4.0 or higher. Figure 8 reveals that 62 percent of the Elections provisions and 50 percent of the Amendment provisions received a mean score of 4.0 or higher. In contrast, 0 percent of the provisions related to Special Sections, Principles or Symbols, or International Law did so (or, in other words, no provisions related to those three categories are included in the 87 “important” variables according to our definition).

Table 3. “Important” Constitution Provisions by Mean Score. This table reports the set of constitutional provisions that have an average importance (measured across survey respondents) larger than 4 on a scale of 5.

Figure 8. Share of “Important” Provisions by Category. This figure reports the category of provisions with the highest mean importance scores, by question. Scores have been encoded to 1-5 from categories “Very Unimportant”, “Somewhat Unimportant”, “Neutral”, “Somewhat Important”, and “Very Important”.

We link our identified set of 87 “important” provisions to master data from the Comparative Constitution Project’s database. We did so using a crosswalk between the Constitute provisions and the CCP variables developed by the members of the CCP team. When using this cross walk, it is important to note that some of these 87 provisions correspond to multiple variables in the CCP data. In these situations, we coded the provision as being present if any one of the variables that corresponds to that provision was present in a given country-year. We then calculated the number of the 87 provisions each country had in each year since they have had a constitution coded by the CCP in place.

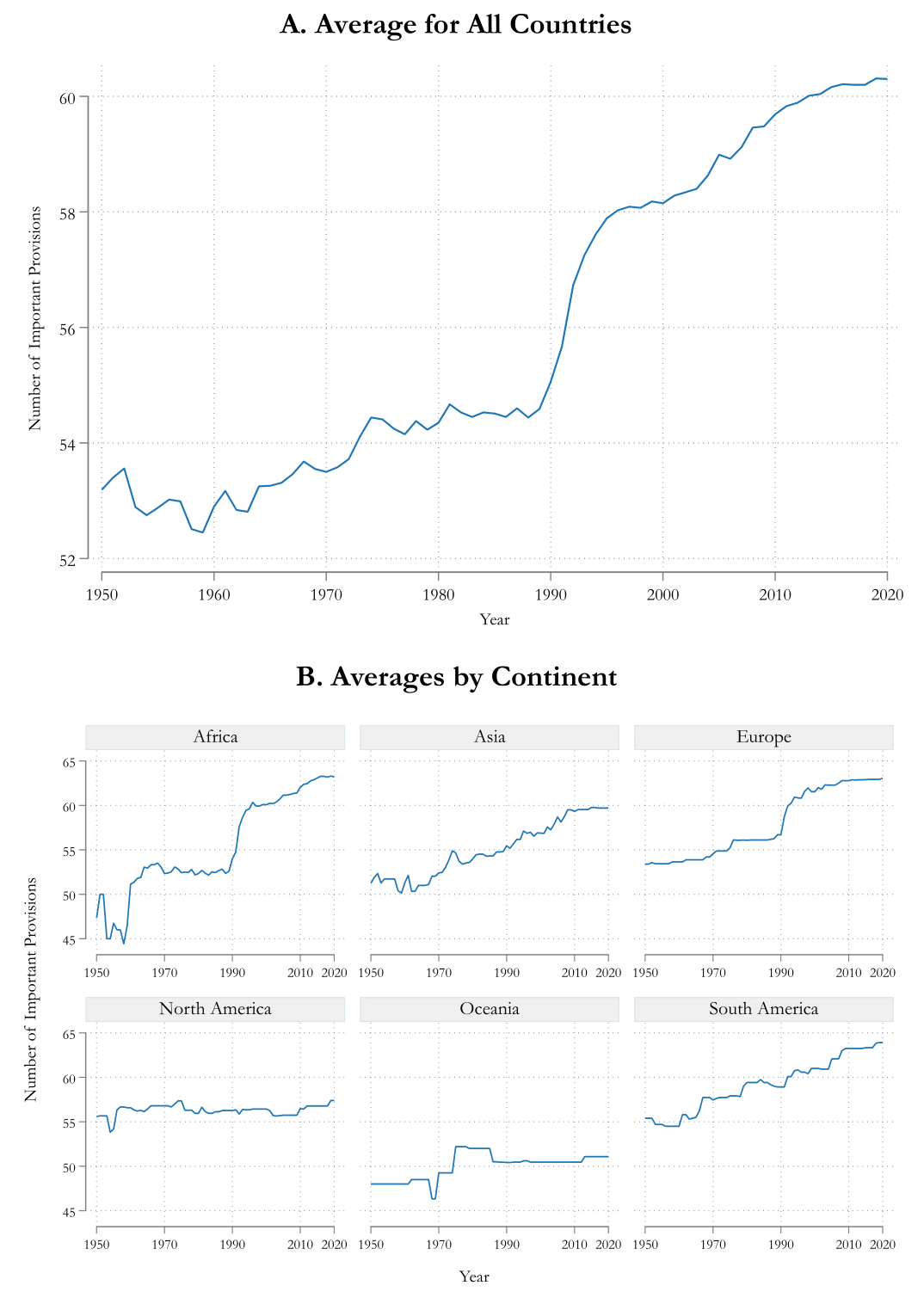

The result is an index reporting the number of these characteristics at the country-year level. To illustrate this index, Panel A of Figure 9 plots the average number of “important” provisions included in countries’ constitutions over time from 1950 to 2020. It shows that, on average, countries’ constitutions included roughly 53 of the 87 important provisions in 1950, and roughly 60 of the 87 important provisions by 2020. Panel B of Figure 9 breaks out these results by continent. It reveals that, by 2020, countries in Europe and Africa have the highest average number of important provisions today, followed closely by South America and Asia, while North America and Oceania have the lowest average number of important provisions.

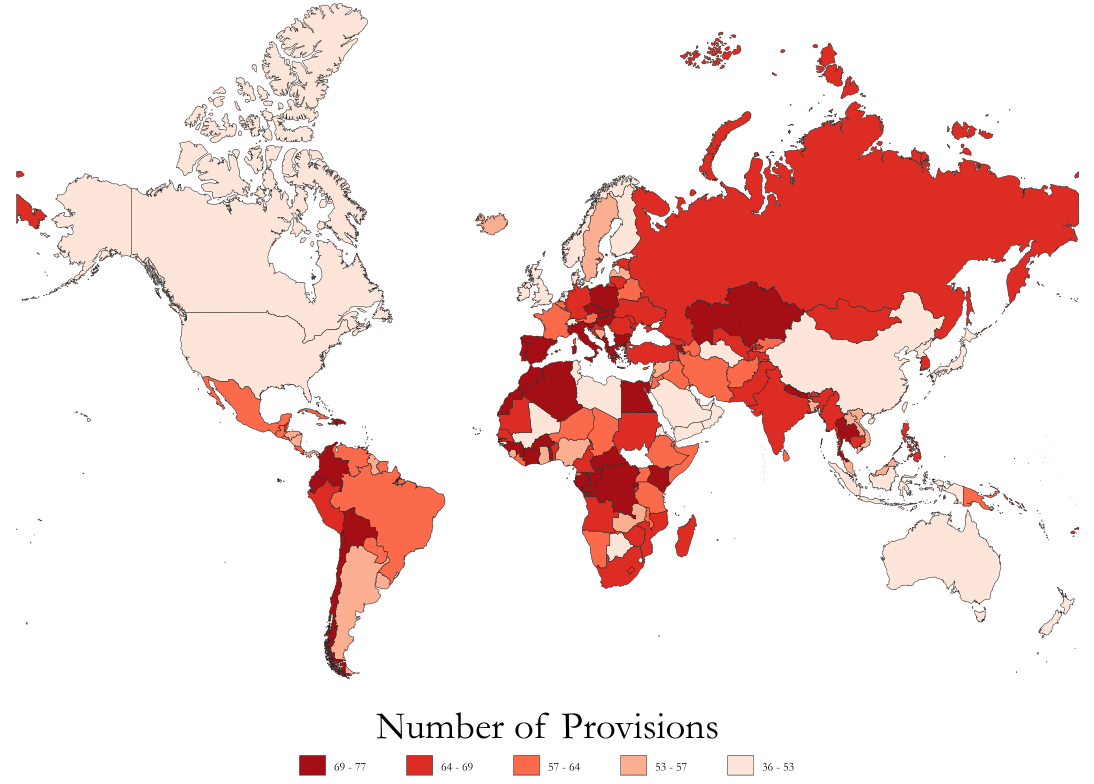

These trends are confirmed by Figure 10, which reports a heat map showing the number of important provisions by country in 2020. The countries are broken into quintiles. The number of provisions ranges from 36 (New Zealand) to 77 (Armenia and the Republic of Congo). The lowest quintile includes many common law countries, including Australia, Canada, New Zealand the United Kingdom, and the United States.17 Many countries in South America. At the other end of the spectrum, many countries in Northern Africa, Europe, and Eurasia have the largest number of important provisions in their constitution.

The results in Figures 9 and 10 should be interpreted carefully, as lower numbers do not necessarily mean that the country has failed to address important issues in its constitution. Rather, the 87 important provisions should be conceptualized as a menu that includes a large number of interchangeable provisions (see Table 3). For example, common law countries typically entrust any constitutional review powers to a supreme court, while civil law countries typically assign such powers to a specialized constitutional court. Common law countries (with notable exceptions like Myanmar) thus will not have the six core provisions related to constitutional courts, and civil law countries (with notable exceptions like Iraq) will not have the three core provisions related to supreme courts. Similarly, countries structured as single-executive presidential systems will not have the eight core provisions creating the head of government as a second executive; and countries with unicameral legislatures will not have the core provision related to a second legislative chamber. Colloquially, importance thus means that “when present, this provision fills an important function in how the government actually operates” and not “this provision must be present for the country to function”.

Figure 9. Share of “Important” Provisions by Category. This figure reports the category of provisions with the highest mean importance scores, by question. Scores have been encoded to 1-5 from categories “Very Unimportant”, “Somewhat Unimportant”, “Neutral”, “Somewhat Important”, and “Very Important”.

Figure 10. Number of Important Provisions in National Constitutions. This map reports the number of 87 “important” constitutional provisions listed in Table 3 that countries had as of 2020.

The results reported in Part 4 focused on the ratings for countries in general. But, as we explained in Part 2, we also separately rated the importance of provisions for three specific kinds of countries: functioning democracies, new democracies, and divided democracies. We now turn to looking at the results for these specifics contexts.

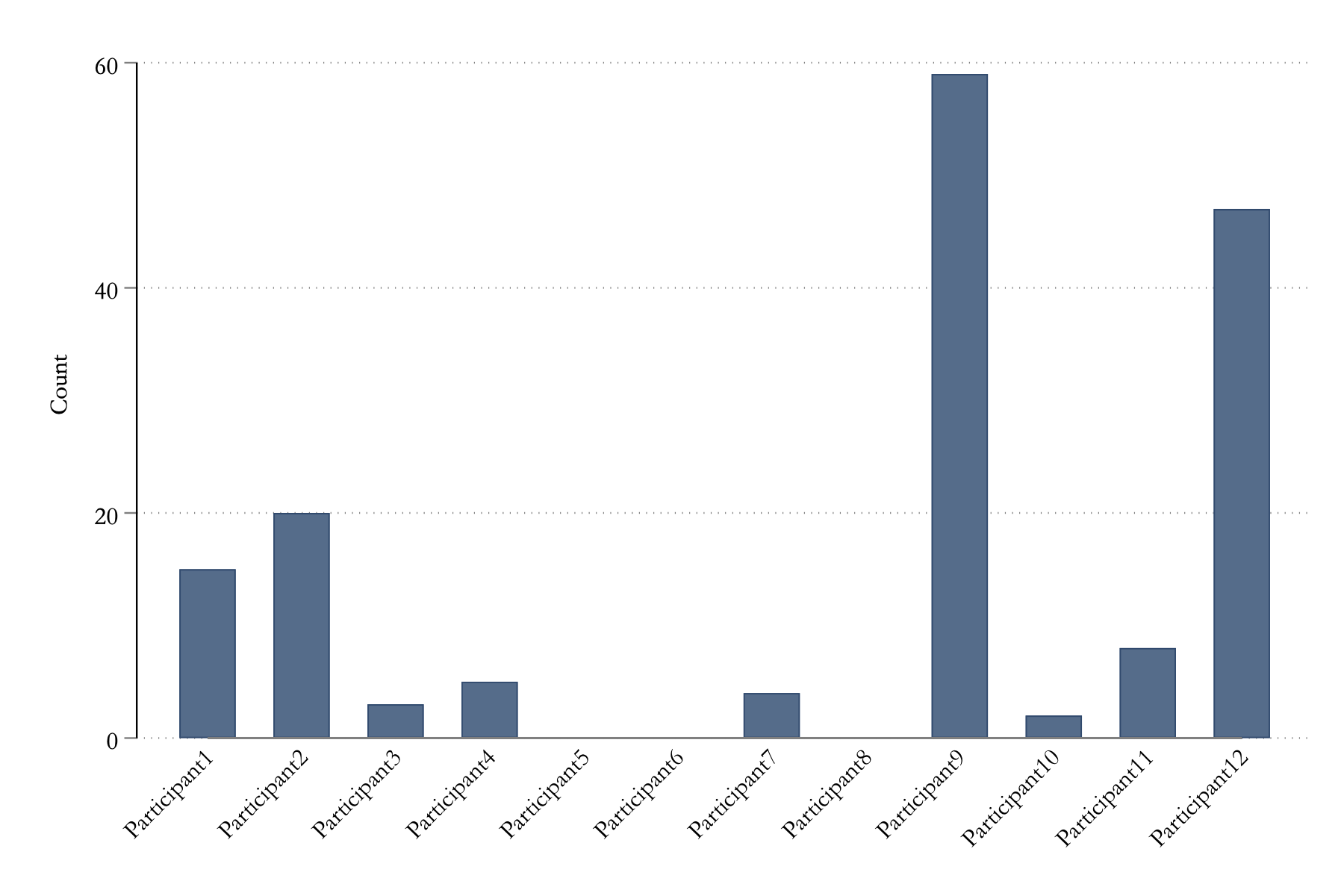

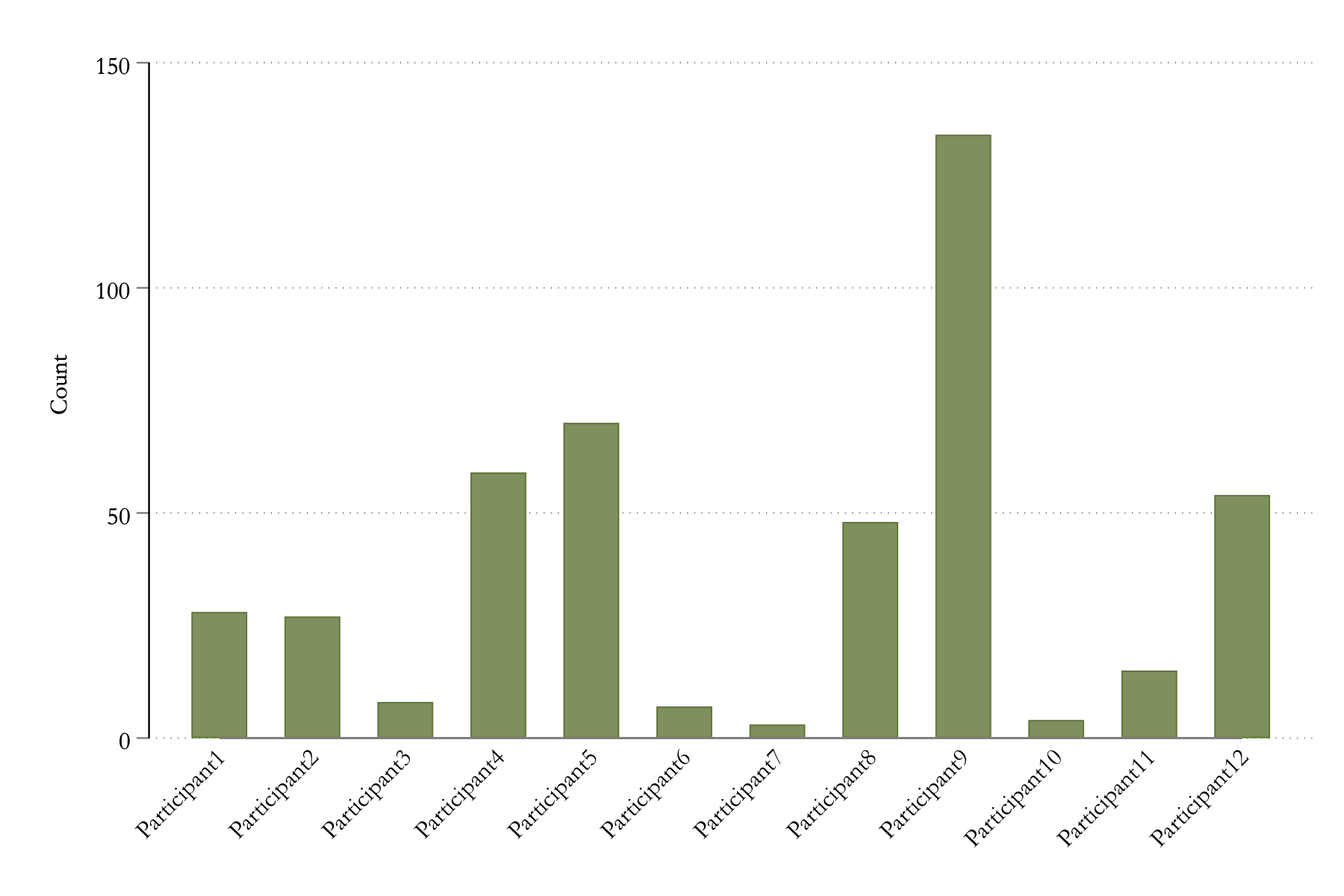

To begin, Figure 11 reports the number of provisions for which each respondent gave a different answer when asked to rate the provisions’ importance for this specific type of country compared to countries in general.18 For instance, if an expert rated all 340 provisions as being “neutral” when asked the general question and all 340 provisions as being “neutral” when asked the question about functioning democracies, then there would be 0 differences between their general ratings and their functioning democracy ratings. On the other hand, if an expert rated all 340 provisions as being “neutral” when asked the general question and all 340 provisions as being “very important” when asked the question about functioning democracies, then there would be 340 differences between their general ratings and their functioning democracy ratings.

A. Functioning Democracy

B. New Democracy

C. Divided Democracy

Figure 11. Different Responses by Question. Panel A through C report the count of provisions where the survey respondent indicated a different answer for respectively functioning, new, and divided democracies, relative to their answer for countries in general.

The results in Figure 11 reveal notable differences in how frequently the experts adjusted their answers for the three specific kinds of countries. For instance, when rating functioning democracies, three experts gave ratings that had zero differences to their general ratings, whereas two experts changed their ratings for nearly 60 constitutional provisions. On average, the number of different responses was 13.6 for functioning democracies compared to the general ratings, 38.1 for new democracies compared to the general ratings, and 32.9 for divided democracies compared to the general ratings. This suggests most experts are inclined to think that the importance of constitutional design choices depends on the type of country.

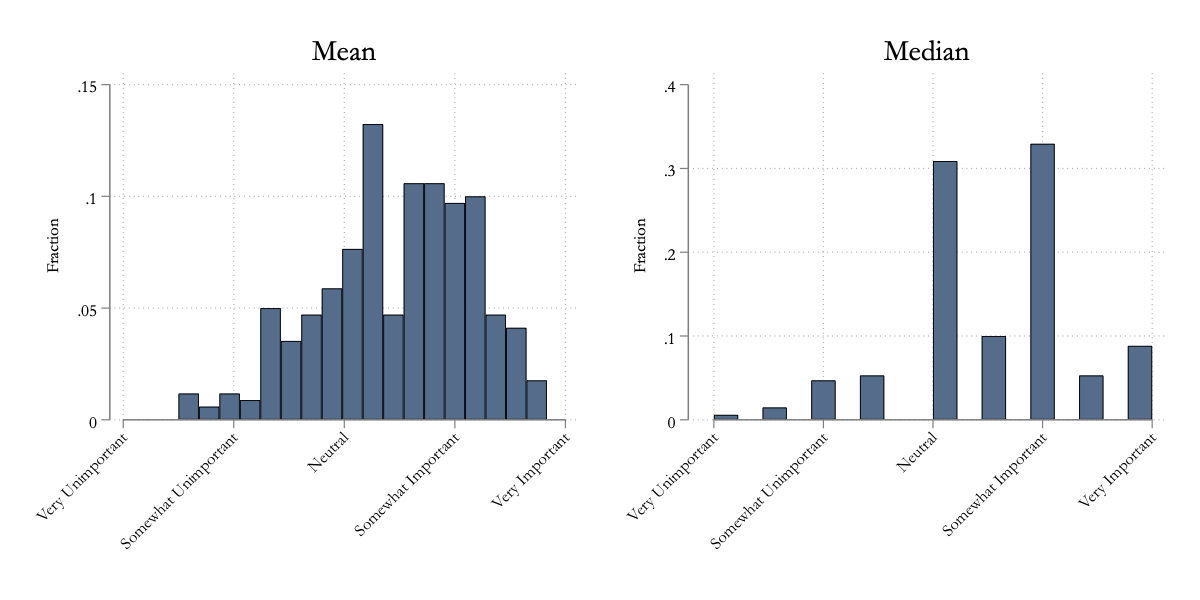

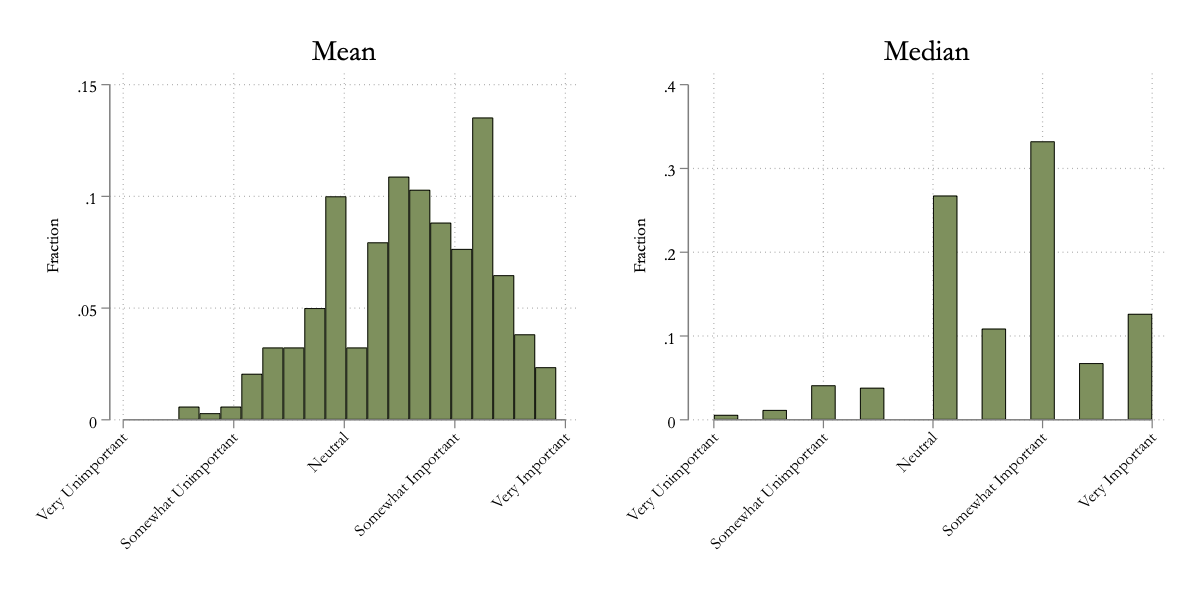

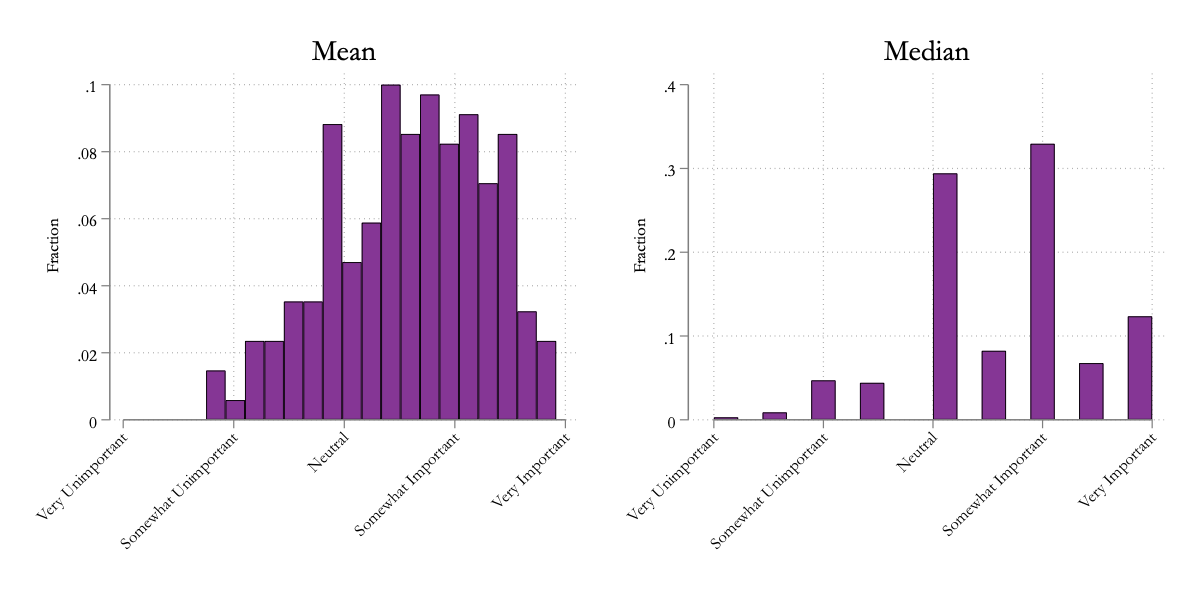

Next, Figure 12 reports the distributions of mean and median responses for these specific types of countries. When compared to Figure 5, which reported these distributions for the general case, the distributions in Figure 12 are skewed slightly further to the right (i.e., more important). When looking at the mean responses, for the general case, 72.1 percent of the constitutional provisions had a mean rating of higher than 3.0 on our five-point scale, as compared with 72.3 percent for functioning democracies, 75.0 percent for new democracies, and 75.3 percent for divided democracies. Zooming in on provisions with a mean rating of 4.0 or higher (for the general case, these are the 87 important provisions discussed above), we find that they comprise 25.6 percent of the provisions for the general country case and for functioning democracies, 33.8 percent for new democracies, and 33.5 percent for divided democracies.

A. Functioning Democracy

B. New Democracy

C. Divided Democracy

Figure 12. Distribution of Responses by Type of Country. This figure represents the mean (left panels) and median (right panels) score distribution by provision, attributed by the survey respondents across questions. Scores have been encoded to 1-5 from categories “Very Unimportant”, “Somewhat Unimportant”, “Neutral”, “Somewhat Important”, and “Very Important”.

Figure 13. Mean Importance by Category of Variable. This figure reports the mean score for provisions, grouped by category for each of the three democracy types included in our survey.

Finally, Figure 14 recreates Figure 7 by plotting the average standard deviations against their average levels of mean importance. Like with responses for countries in general, there is a clear negative relationship between standard deviations and levels of agreement for each of these three sets of democracies. This again indicates that, when experts agreed the most, it was over provisions that the members also believed had greater importance.

Figure 14. Provision Importance and Agreement Levels by Category. This figure reports the relationship between mean importance and mean standard deviation, grouped at the category level for functioning, new, and divided democracies.

There are hundreds of different provisions that are commonly included in countries’ national constitutions, and there is relatively little research directly exploring which provisions are likely to be particularly important for a country’s governance. To try to gain insight into current thinking on which provisions are likely to be most important, we assembled as a group of twelve comparative constitutional law scholars and set out to rate systematically and collectively the importance of constitutional provisions. Our results identify dozens of provisions, and several categories of provisions, that were systematically rated as important, particularly those related to topics like the structure of government; and our results also identify some provisions, and a few categories of provisions, that were consistently rated as being less important, particularly those related to symbolic issues. Our results also point to areas with more and less expert consensus. Specifically, we found high agreement regarding the importance of Amendment provisions—and the agreement on these provisions was even higher for new and divided democracies—but less agreement with respect to the importance of Principles and Symbols, Special Sections, Rights and Duties, and the Judiciary. Overall, it appears that experts stand more divided in their evaluation of values than structure.

Our hope is that this exercise can help guide research on constitution-making going forward. Research time and resources are scarce. Gaining collective insight on the important issues, areas, and challenges in our field can help focus attention on the constitutional questions that are most in need of research—including exposing issues that, despite being rated as important, receive little scholarly attention. Moreover, for quantitative research, a list of the provisions that are likely to be more important can be a particularly valuable tool to aid data reduction exercises.

In addition to assisting future research, it is possible that our ratings may be useful to constitutional drafters. In constitution-making exercises, political actors and civil society activists might likewise want to direct their attention specifically to the topics that are likely most important for the nature of constitutional governance. To illustrate, many contemporary constitution-making efforts focused on elaborating on rights and duties; our findings draw attention to the importance of institutions. Of course, real life constitution-making is not necessarily either/or: a country can constitute both rights and institutions; and, some rights ranked as very important on our index (primarily political rights and equality). Yet constitution-making processes often occur under significant time constraints and sociopolitical pressures; they require compromise, and hence priorities-setting. Trading stronger institutions for a more expansive bill of rights or a set of symbolic concessions could be a real dilemma for constitutional drafters. Having a sense of the most important issues to be addressed in constitution-making can help ensure these issues receive attention in the drafting process, regardless of which (often narrow) set of issues have salience in public or political debates at the time. Importantly, our study does not aim to set a particular understanding of constitutional importance in stone, but to set in motion a concept and method about how to arrive at a common understanding of constitutional importance.

Albert, Richard. 2014. “Constitutional Disuse or Desuetude.” Boston University Law Review 94(3): 1029–1081.

Albert, Richard. 2019. Constitutional Amendments: Making, Breaking, and Changing Constitutions. Oxford University Press.

Altan, Erensu and Mila Versteeg. 2023. “Constitutional Duties.” American Journal of Comparative Law (forthcoming).

Besso, Michael. 2005. “Constitutional Amendment Procedures and the Informal Political Construction of Constitutions.” Journal of Politics 67(1): 69–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468–2508.2005.00308.x.

Bradford, Anu, and Adam Chilton. 2018. “Competition Law Around the World from 1889 to 2010: The Competition Law Index.” Journal of Competition Law & Economics 14(3): 393–432. https://doi.org/10.1093/joclec/nhy011.

Bradford, Anu, and Adam Chilton. 2019. “Trade Openness and Antitrust Law.” Journal of Law and Economics 62(1): 29–65. https://doi.org/10.1086/701438.

Bradford, Anu, Adam S. Chilton, Chris Megaw, and Nathaniel Sokol. 2019b. “Competition Law Gone Global: Introducing the Comparative Competition Law and Enforcement Datasets.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 16(2): 411–443. https://doi.org/10.1111/jels.12215.

Cruz, Andrés, Zachary Elkins, Roy Gardner, Matthew Martin, and Ashley Moran. 2023. “Measuring Constitutional Preferences: A New Method for Analyzing Public Consultation Data.” PLOS ONE 18(12). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0295396.

Chilton, Adam, and Mila Versteeg. 2016. “Do Constitutional Rights Make a Difference?” American Journal of Political Science 60(3): 575–589. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12239.

Chilton, Adam and Mila Versteeg. 2018. “Courts’ Limited Ability to Protect Constitutional Rights.” University of Chicago Law Review 85: 293–335.

Aucoin, Louis. 2004. “The Role of International Experts in Constitution-Making: Myth and Reality.” Georgetown Journal of International Affairs 5(1): 89–95.

Barak-Corren, Netta. 2023. “The Levin-Rothman Plan for Altering the Israeli Justice System: A Comprehensive Analysis and Proposal for the Path Forward.” Available at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1_r-5u_lT6TIc27SjireMrlNux1roM72C/view.

Chernykh, Svitlana and Zachary Elkins. 2021. “How Constitutional Drafters Use Comparative Evidence.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 24(6): 529-556. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2021.1990737.

Chilton, Adam, and Mila Versteeg. 2020. How Constitutional Rights Matter. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chilton, Adam, and Mila Versteeg. 2022a. “Introduction: A Second Wave of Comparative Constitutional Studies.” Journal of Legal Studies 51(2): 321–328 (2022)

Chilton, Adam, and Mila Versteeg. 2022b. “Small-c Constitutional Rights.” International Journal of Constitutional Law 20(1): 141-176. https://doi.org/10.1093/icon/moac004.

Chilton, Adam, and Mila Versteeg. 2023. “Legal Origins and Human Rights Law.” Rutgers International Law and Human Rights Journal 3(3): 26–48.

Choudhry, Sujit. 2008. “Bridging Comparative Politics and Comparative Constitutional Law: Constitutional Design in Divided Societies.” In Constitutional Design for Divided Societies: Integration or Accommodation?, edited by Sujit Choudhry, 3-40. Oxford University Press.

Daley, Tom G. 2017. “The Alchemist: Questioning our Faith in Courts as Democracy-Builders”. Global Constitutionalism. 6(1): 101–130. doi:10.1017/S204538171600023X.

Dixon, Rosalind and David Landau. 2020. “Constitutional End-Games: Making Presidential Term Limits Stick.” Hastings Law Journal 71(2): 359–418.

Eisenstadt, Todd A., A. Carl LeVan, and Tofigh Maboudi. 2017. Constituents Before Assembly: Participation, Deliberation, and Representation in the Crafting of New Constitutions. Cambridge University Press.

Elkins, Zachary, Tom Ginsburg, and James Melton. 2009. The Endurance of National Constitutions. Cambridge University Press.

Elkins, Zachary, Tom Ginsburg, James Melton, Robert Shaffer, Juan F. Sequeda, and Daniel P. Miranker. 2014. “Constitute: The world’s Constitutions to Read, Search, and Compare.” Journal of Web Semantics 27–28: 10-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.websem.2014.07.006.

Elkins, Zachary and Tom Ginsburg. 2021. “What Can We Learn from Written Constitutions?” Annual Review of Political Science 24: 321–343. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-100720-102911.

Ginsburg, Tom. 2021. Democracies and International Law. Cambridge University Press.

Ginsburg, Tom and Mila Versteeg. 2023. “The Constitutionalization of Democracy.” Journal of Democracy 34(4): 36-50.

Guelke, Adrian. 2012. Politics in Deeply Divided Societies. Polity Press.

Gutmann, Jerg, Katarzyna Metelska-Szaniawska, and Stefan Voigt. 2023. “The Comparative Constitutional Compliance Database.” Review of International Organizations (forthcoming).

Hirschl, Ran. 2016. Comparative Matters: The Renaissance of Comparative Constitutional Law. Oxford University Press.

Hudson, Alexander. 2021. The Veil of Participation: Citizens and Political Parties in Constitution-Making Processes. Cambridge University Press.

Issacharoff, Samuel. 2015. Fragile Democracies: Contested Power in the Ara of Constitutional Courts. Cambridge University Press.

Landau, David. 2012. “The Reality of Social Rights Enforcement.” Harvard International Law Journal 53(1): 319–378.

Landis, J. Richard, and Gary G. Koch. 1977. “The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data.” Biometrics 33(1): 159-174. https://doi.org/10.2307/2529310.

Law, David S., and Mila Versteeg. 2011. “The Evolution and Ideology of Global Constitutionalism.” California Law Review 99(5): 1163–1257.

Lewkowicz, Jacek and Anna Lewczuk. 2023. “Civil Society and Compliance with Constitutions.” Acta Politica 58(1): 181–211. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-022-00240-z.

Simmons, Beth A. 2009. Mobilizing For Human Rights: International Law in Domestic Politics. Cambridge University Press.

Tew, Yvonne. 2017. “Comparative Originalism in Constitutional Interpretation in Asia.” Singapore Academy Law Journal 29(3): 719–742.

Versteeg, Mila and Emily Zackin. 2016. “Constitutions Unentrenched: Toward an Alternative Theory of Constitutional Design.” American Political Science Review 110(4): 657-674. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055416000447.

Voigt, Stefan. 2021. “Mind the Gap: Analyzing the Divergence Between Constitutional Text and Constitutional Reality.” International Journal of Constitutional Law 19(5): 1778–1809. https://doi.org/10.1093/icon/moab060.

Waldron, Jeremy. 2006. “The Core of the Case Against Judicial Review.” The Yale Law Journal 115(6): 1346–1406.

University of Texas, richard.albert@law.utexas.edu, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5212-5292.↩︎

Hebrew University of Jerusalem, barakcorren@huji.ac.il, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0941-5686.↩︎

University of Texas, danbrinks@austin.utexas.edu, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1722-4708.↩︎

University of Chicago, adamchilton@uchicago.edu. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3638-6550.↩︎

University of New South Wales, rosalind.dixon@unsw.edu.au, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6613-8032.↩︎

University of Texas, zelkins@austin.utexas.edu, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7932-773X.↩︎

University of Chicago, tginsburg@uchicago.edu, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3128-3392.↩︎

University of Toronto, ran.hirschl@utoronto.ca, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3025-8040.↩︎

Florida State University, dlandau@law.fsu.edu, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4990-0400.↩︎

University of Texas, amoran@austin.utexas.edu, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5969-2134.↩︎

Georgetown University, yvonne.tew@law.georgetown.edu.↩︎

University of Virginia, versteeg@law.virginia.edu, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5231-9847.↩︎

In addition to relying on the advice of experts, constitutional drafters can also directly engage with comparative evidence themselves (e.g., Chernykh and Elkins 2021).↩︎

The two provisions in the Amendment category are about (1) the amendment procedure and (2) unamendable provisions; the two provisions in the Special Sections category are about (1) the existence of a pre-amble and (2) provisions that outline transitional processes.↩︎

See Tables A1, A2, A3, and A4 for complete responses for each of the four prompts.↩︎

See, e.g., Albert (2019) at 2 (“No part of a constitution is more important than the procedures we use to change it. Whether codified or uncodified, the rules of constitutional amendment stand atop a constitution's hierarchy of norms and sit at the base of its architecture, simultaneously stabilizing the constitution's foundation and authorizing reinforcements when needed.”).↩︎

See Chilton and Versteeg (2023) for a discussion of how common law countries have taken different approaches than civil law countries in their constitutional commitments.↩︎

Appendix Tables A5, A6, and A7 report the specific provisions that have the largest changes in responses for each of the three democracy types compared to the responses for countries in general.↩︎