Article History Submitted 3 May 2024. Accepted 13 November 2024. Keywords courts, dissents, judicial behavior, political science, regression analysis |

Abstract This article examines the factors influencing dissenting opinions by judges at the Czech Constitutional Court (“CCC”). We build on the disagreement-identification model and the strategic accounts of dissenting behavior. Our findings do not support the existence of a strong norm of consensus operating at the CCC. However, the complexity of a case, measured by the number of CCC caselaw citations involved, is positively correlated with the probability of a dissenting opinion. Similarly, cases concerning controversial topics are more likely to generate dissents. A placebo test strengthens this finding by demonstrating that randomly chosen, non-controversial topics have minimal impact on dissenting behavior. The effect of voting blocs in the plenary proceedings seems to carry over to the 3-member chamber proceedings. The results also reveal that judges make strategic considerations. When facing a high workload, judges are less likely to write separate opinions, suggesting they prioritize workload management. Lastly, CCC judges do not seem to take into account collegiality costs. |

|---|

“I don’t like them [separate opinions]. (...) Because I am a routine judge, I believe that when a collegiate body reaches a decision, an individual judge should not offer additional commentary solely because they hold a differing view. It undermines the authority of the court.” This perspective, shared by a judge of the Czech Constitutional Court (“CCC”), reflects one of the many possible stances a judge might take towards exercising the right to dissent. This stance is shaped by each judge’s understanding of their role within the CCC and the role of the court itself. The factors influencing a judge’s decision to dissent or not are diverse, encompassing political considerations (Hanretty 2015), strategic considerations (Epstein, Landes, and Posner 2011), and institutional-systemic considerations (Garoupa and Grajzl 2020).

Our paper presents an empirical study of dissenting opinions at the CCC, exploring factors that influence a judge’s decision to dissent.3 We examine both strategic considerations and influences from the identification-disagreement model proposed by Wittig (2016). Specifically, we investigate whether judges are influenced by factors such as workload, professional background, colleagues, or case characteristics. Institutional-systemic influences, like political fragmentation of the legislative body, are beyond the scope of this study.

In the Czech context, empirical legal scholarship on dissenting behavior has been limited, with most studies focusing on the existence of implicit voting blocs in the CCC’s 3rd decade. Due to the lack of publicly available vote records, researchers conducting network analyses have relied on data showing which judges dissented in specific decisions. Findings indicate that the CCC’s third term, spanning 2013 to 2023, is notably polarized, with two primary coalitions of dissenting judges often in opposition (Chmel 2021; Smekal et al. 2021; Vartazaryan 2022). These studies analyze only cases that feature separate opinions, without comparison to decisions where no dissent is recorded. Our paper contributes to the existing literature by examining a broader selection of CCC decisions than previous Czech studies.

We believe the CCC to be a valuable object of study. First, while the CCC’s judicial appointment procedure is similar to that of the U.S. Supreme Court (SCOTUS), its role within the constitutional system aligns more closely with European constitutional courts. This dual alignment allows our research to build upon and contribute to empirical legal studies grounded in both common law and civil law traditions. Secondly, the CCC wields significant influence through its extensive competencies: it may review laws both in abstract and in concrete cases initiated by individual complaints. Moreover, the CCC has broadened its powers to review even constitutional amendments, and it has shown willingness to address politically sensitive cases.4 Thirdly, separate opinions have been permitted at the CCC since its foundation, and their use is now well established. A primary limitation of studying the CCC, however, is the inability to accurately and reliably capture judges’ political preferences, given the lack of information on their individual votes (Martin and Quinn 2002; Hanretty 2012) and the limited variability in the nomination process.5

Our article proceeds as follows. In section 2, we discuss the strategical and the identification-disagreement accounts of dissenting behavior. Therein, we draw hypotheses based on the general theory applied to the specific institutional setup of the CCC. In section 3, we introduce the CCC. We discuss its institutional setup, its procedures and, most importantly, the rules concerning separate opinions. In section 4, we discuss our method, our model, and the operationalization of variables. In section 5, we empirically test the hypotheses and we discuss the results. Section 6 concludes.

Epstein and Knight (2000) argues that judges, as social actors, make choices to achieve certain goals. They (1) make choices based on their expectations regarding the decisions of other actors, and (2) those choices are structured by the institutional setting in which they are made. Rather than focusing solely on judges pursuing politically oriented goals, judges’ self-interest in terms of career progression, higher income, increased leisure time, or reduced workload is highlighted.

Epstein, Landes, and Posner (2011) posit that “a potential dissenter balances the costs and benefits of issuing a dissenting opinion,” noting that judges have “leisure preferences, or, equivalently, effort aversion, which they trade off against their desire to have a good reputation and to express their legal and policy beliefs and preferences (and by doing so, perhaps influence law and policy) through their vote and the judicial opinion explaining their vote in the cases they hear.”

The utility of a dissenting opinion may take the form of the potential to undermine the majority opinion when the dissent is influential and the enhanced reputation that the judge enjoys as the dissenting opinion may be cited in the future by other judges or publicly analyzed by legal scholars. The costs take up two forms: judges strategically take into account collegiality costs. Moreover, judges may reap benefits of averting a dissent whenever they face a high workload so that they free up their hand to take care of more pressing work or to pursue leisure activities (Clark, Engst, and Staton, 2018).

Regarding the issue of collegiality costs arising for a dissenting judge, Epstein, Landes, and Posner (2011, 104) posit that: “The effort involved in these revisions, and the resentment at criticism by the dissenting judge, may impose a collegiality cost on the dissenting judge by making it more difficult for him to persuade judges to join his majority opinions in future cases.” We assume that at the beginning of judges’ terms, they are aware that they will sit together more frequently, and that the prospect of sharing a ten-year term with their colleagues increases the collegiality costs associated with dissenting. Conversely, as their terms draw to a close or the change in composition of the chamber looms, we expect that these collegiality costs will decrease. From this, we formulate our first hypothesis:

H1: The closer the date of the decision to the date at which the composition of a chamber changes, the higher the probability of a judge exercising a dissent.

According to Epstein, Landes, and Posner (2011), “[t]he economic theory of judicial behavior predicts that a decline in the judicial workload would lower the opportunity cost of dissenting [...].” Clark, Engst, and Staton (2018) found that judges have preferences regarding their leisure, which impacts their performance. Specifically, they observed that whenever a team from a U.S. Federal Court judge’s alma mater plays a basketball game, the time taken to process decisions increases for that judge, and the quality of their work decreases. Similarly, Brekke et al. (2023) found that judges at the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) consider their workload when issuing orders. Engel and Weinshall (2020) conducted a quasi-experiment on Israeli judges and discovered that a reduction in judges’ workload affects their decision-making. Furthermore, Epstein, Landes, and Posner (2011) found that judges strategically choose to write fewer dissenting opinions whenever the workload on their court increases. However, the evidence is not universal. Songer, Szmer, and Johnson (2011) found no relationship between workload and the dissent rate at the Supreme Court of Canada. Therefore, our second hypothesis suggests:

H2: The higher the workload of a judge at the time of a decision, the lower the probability of them exercising a dissent.

Outside of Czechia and within the civil law context, Kelemen (2017) provides a primarily theoretical comparative overview of the various regimes of dissenting behavior across European courts. Hanretty has utilized the dissenting behavior of Spanish and Portuguese judges to conduct a point estimation of the “political” positions of judges (Hanretty 2012), as well as to investigate what dissent reveals about the dimensions of disagreement in the Estonian Supreme Court (Hanretty 2015) and the British Law Lords (Hanretty 2013). Additionally, Garoupa and Grajzl (2020) studied the influence of political fragmentation on the dissenting behavior of Slovenian and Croatian judges. Most importantly, Wittig (2016) proposed and empirically tested a theoretical identification-disagreement model of dissenting behavior tailored to civil law legal systems, specifically focusing on the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany (“GFCC”).

Wittig argues that traditional theories of dissent derived from the common law context have limited explanatory power within the civil law context. In civil law systems, judges operate within a different framework, bound by distinct procedural rules, which provides them with varying avenues—sometimes broader, sometimes more limited—to express their policy preferences or strategic considerations. To address these challenges, Wittig introduces a non-formal model of dissenting behavior termed as the identification-disagreement model. It consists of two dimensions: the level of disagreement and the judges’ stance and degree of self-identification with their role as a judge, referred to as the norm of consensus. According to Wittig, separate opinions are “a function of a judge’s identification with the norm of consensus and the level of disagreement among judges” (Wittig 2016, 74–75). We base our theory on the identification-disagreement model because the CCC shares institutional similarities with the GFCC, as we show bellow. Therefore, the hypotheses are as follows:

H3: The probability of a judge exercising a dissent is higher for judges with low norm-identification than for judges with high norm-identification.

H4: The probability of a judge exercising a dissent is higher in cases with a higher level of disagreement potential than in cases with a lower level of disagreement potential.

We now flesh out the norm of consensus and then we move on to disagreement.

Calderia and Zorn (1998, 876–877) define a norm as “a long-run equilibrium outcome that underpins the interaction between individuals and reflects common understandings of what is acceptable behavior in given circumstances.” The norm of consensus, in turn, delineates the level of dissent that is acceptable within any given court (Narayan and Smyth 2005; Wittig 2016, 75). First, in civil law traditions, unlike in their U.S. counterpart, the prevailing understanding of the norm of consensus is that a court should not display disagreement. Second, the degree of adherence to this norm varies among judges (Wittig 2016, 75).6

How to capture the judges’ identification with the norm of consensus? The judges who are socialized within the judiciary are more likely to adhere to its values than those entering from a career outside the judiciary. In other words, CCC judges that are appointed from the ranks of the judiciary are expected to adhere to the norm of consensus more than the others. That applies especially strongly within the civil legal system, in which voicing a disagreement is usually prohibited within the ordinary judiciary. Bricker (2017) notes that unlike the SCOTUS, which now is almost exclusively comprised of career judges, European constitutional judges arrive to the court from diverse paths: the ordinary court system, law firms, academia, or politics. Moreover, legal professions in civil-law systems have been comparatively much more tightly embedded into a unified state bureaucracy (Garoupa and Grajzl 2020).

In Czechia, apart from on the CCC and the Supreme Administrative Court7, no separate opinions are even legally allowed.8 Therefore, the CCC judges coming out of the judiciary are socialized in an environment in which voicing a dissent is not permitted. On the other hand, lawyers or CCC judges recruited from the ranks of politicians or scholars are not socialized within the judiciary and are used to defending their own opinion, or at least not required to hide their disagreement. However, we expect that the difference between the professions should wane over time as the non-judicial judges get accustomed to the role of a CCC judge. Our hypothesis 5 suggests:

H5: The difference between the probability of observing a separate opinion of judges coming from judiciary and of judges coming outside judiciary is larger at the beginning of judges’ terms than at their end.

Research into the effect of judges’ professional backgrounds is not a new endeavor. Garoupa, Salamero-Teixidó, and Segura (2022) found that the individual decision to attach a separate opinion among judges on the Spanish Council of State depends on the judge’s professional background. However, the findings did not align with our theoretical expectations: only former politicians were less likely to attach a separate opinion, while former judges and lawyers were more likely to do so. Although the studies cited above support the presence of such an effect, Garoupa and Grajzl (2020) found no evidence of the influence of judges’ backgrounds—such as their prior careers or education—in their comparative study of Slovenia and Croatia.

Disagreement on a bench arises when judges diverge in their opinions during discussions, with a judge expressing an objection to the majority view. The sources of disagreement are varied.

Landa and Lax (2007/2008) identify multiple theoretical sources of disagreement based on the case-space model. The most evident source is factual disagreement, where different judges may interpret the facts of a case differently. Additional sources include disagreement over which dimensions are relevant under a given legal rule, disagreement about thresholds within those dimensions, and other related sources, all of which can be summarized as disagreement over the legal rule. Regarding the impact of disagreement on dissent, Wittig (2016) found a positive correlation between legal complexity and judges’ dissenting behavior. Similarly, Bricker (2017) observed a comparable effect in studies of the German, Polish, Latvian, and Slovenian constitutional courts.

To this end, we simplify the potential for disagreement into two similar characteristics that concern the facts and the legal rule: case complexity and case controversy. Case complexity in our understanding refers to the number of legal issues that a case has touched upon. In line with Landa and Lax (2007/2008) we suppose that the more legal rules there is in play in any given case, the more room for disagreement about rules. Case controversy refers to the facts. We obtain the following two hypotheses:

H6a: The more legally complex a case is, the higher is the probability of a judge exercising a dissent.

H6b: The more controversial a case is, the higher is the probability of a judge exercising a dissent.

Within the CCC, we can observe a special example of circumstances giving rise to higher levels of disagreement. Chmel (2021), Smekal et al. (2021), and Vartazaryan (2022) found that the third term of the CCC between 2013–2023 is rather polarized and that there are two voting blocs of judges that clash against each other in the plenary decisions. If the relationships between the judges are strained from the plenary proceedings, they should also carry over to the chamber hearings. If this shows to be true, it would provide a robustness check for the two coalition theory as well as for the Wittig’s identification-disagreement model. Therefore, our final hypothesis suggests:

H7: Having a chamber composed of members of both judicial coalitions increases the probability of a judge exercising a dissent.

We now introduce the CCC, its institutional and procedural background, its powers as well as its composition. The CCC consists of fifteen judges, out of which one is the president of the CCC, two are vice presidents and twelve associate judges (following the terminology of Kosař and Vyhnánek 2020). These fifteen judges are appointed by the president of the Czech republic upon approval of the Senate, the upper chamber of the Czech two-chamber Parliament. The judges enjoy ten-year terms with the possibility of reelection; there is no limit on the times a judge can be re-elected. The three CCC functionaries are unilaterally appointed by the Czech president.

The appointment procedure is similar to how the SCOTUS judges are appointed as the procedure lies in the hands of the president of the republic and the upper chamber. The minimum requirement for a CCC nominee are 40 years of age, a clean criminal record, a finished legal education and experience in the legal field. Other than that, the nomination is left to the consideration of the president of the republic. After a nomination, the nominee is firstly interviewed in the constitutional law committee of the Senate, which produces a non-binding recommendation for the plenary Senate hearing. The final, binding decision is then made by a simple majority of the Senate plenary hearing. This procedure has led to a situation, in which there is very little variance as to the appointment background of the judges. First, there is no nominating political party akin to the US or Spanish contexts (Hanretty 2012). Second, because the CCC was established in 1993 and filled within roughly a year of its establishment and because the term of the Czech president is five years and all the three Presidents, who’d finished their term at the time of writing this article, have been elected twice (for ten years in total), each president has had the chance to appoint all the fifteen members of “their” CCC. Therefore, the first term of the CCC has been termed the Václav Havel, the second the Václav Klaus and the third Miloš Zeman terms of the CCC.

Regarding the competences, the CCC is a typical Kelsenian court inspired mainly by the GFCC. The CCC enjoys the power of abstract constitutional review, including constitutional amendments. The abstract review procedure is initiated by political actors (for example MPs) and usually concerns political issues. Moreover, an ordinary court can initiate a concrete review procedure, if that court reaches the conclusion that a legal norm upon which its decision depends is not compatible with the constitution. Individuals can also lodge constitutional complaints before the CCC. Lastly, the CCC can also resolve competence disputes, ex ante review international treaties, decide on impeachment of the president of the republic, and it has additional ancillary powers (for a complete overview, see Kosař and Vyhnánek 2020).

The CCC is an example of a collegial court. From the perspective of the inner organization, the CCC can decide in four bodies: (1) individual judges in the role of a judge rapporteur, (2) three-member chambers (senáty),9 (3) the plenum (plénum), and (4) special disciplinary chamber. The three-member chambers and the plenum play a crucial role. In general, the plenum is responsible for the abstract review, whereas the chambers are responsible for the individual constitutional complaints. The plenum is composed of all judges, whereas the four chambers are composed of the associate judges. Neither the president of the CCC nor their vice-presidents are permanent members of the chambers. Until 2016, the composition of the chambers was static. However, in 2016, a system of regular two-year rotations was introduced, wherein the president of the chamber rotates to a different one every two years.

In the chamber proceedings, decisions on admissibility must be unanimous, whereas decisions on merits need not be. Therefore, a simple majority of two votes is necessary to pass a decision on merits. In the plenum, the general voting quorum is a simple majority and the plenum is quorate when there are ten judges present. The abstract review is one of the exceptions that sets the quorum higher, more specifically to nine votes.

A judge rapporteur plays a crucial role (Chmel 2017; Hořeňovský and Chmel 2015 study the large influence of the judge rapporteurs at the CCC). Each case of the CCC gets assigned to a judge rapporteur. The assignment is regulated by a case allocation plan. They are tasked with drafting the opinion, on which the body then votes. The president of the CCC (in plenary cases) or the president of the chamber (in chamber cases) may re-assign a case to a different judge rapporteur if the draft opinion by the original judge rapporteur did not receive a majority of votes. Unfortunately, the CCC does not keep track of these reassignments.

The act on the CCC allows for separate opinions. They can take two forms: dissenting or concurring opinions. Each judge has the right to author a separate opinion, which then gets published with the CCC decision. It follows that not every anti-majority vote implies a separate opinion, it is up to the judges to decide whether they want to attach a separate opinion with their vote. Vice versa, not every separate opinion implies an anti-majority vote, as the judges can attach a concurring opinion. In contrast to dissenting opinion, when a judge attaches a concurring opinion, they voted with the majority but disagree with its argumentation.10 Unfortunately, it is difficult to conduct research on the dissent aversion because the voting is kept secret.

The room for the dissenting judge and the majority to address an opinion of each other differs between the two bodies. Based on our qualitative research, there is less back and forth interplay between the judges, more akin to the SCOTUS context, and most of the communication is handled remotely in the chamber proceedings, whereas the plenum meets regularly to discuss the cases in person (Vartazaryan and Paulík 2024). Despite that, procedurally speaking, the process of generating separate opinions is the same. In both cases, the rapporteurs are informed about the outcome of the vote, which is filed in the voting record. The separate opinion is then sent to the judge rapporteur before the decision is announced, as it cannot be added until after the announcement. It is important to note that judges have the possibility, not the obligation, to dissent. In other words, there is room for judges to give way to strategic considerations.

We now move on to the empirical part of our paper. First, in section 4.1 we describe the data we collected. Second, in section 4.2 we explain how we operationalized the variables included in our models. Last, in section 4.3 we explain our identification strategy.

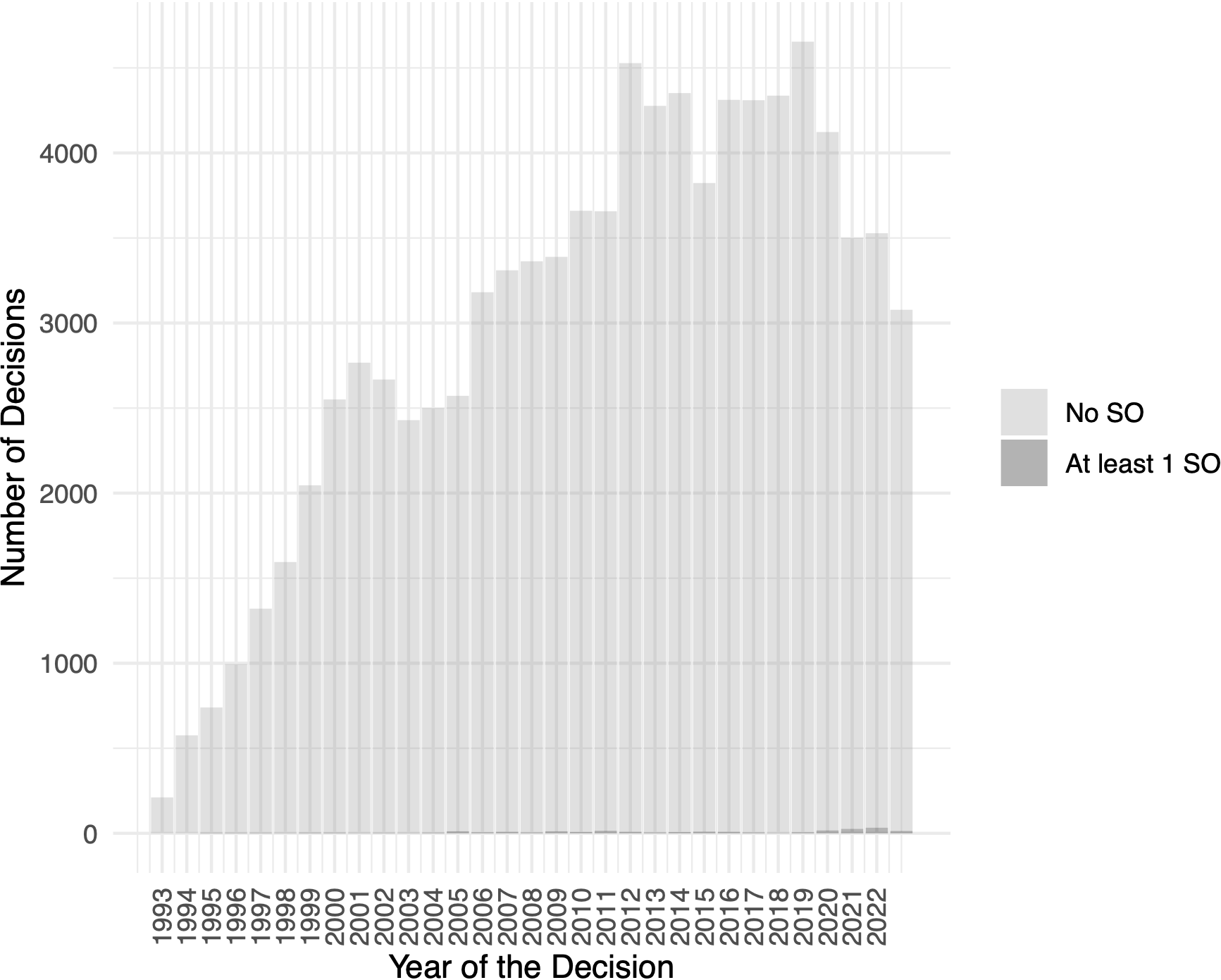

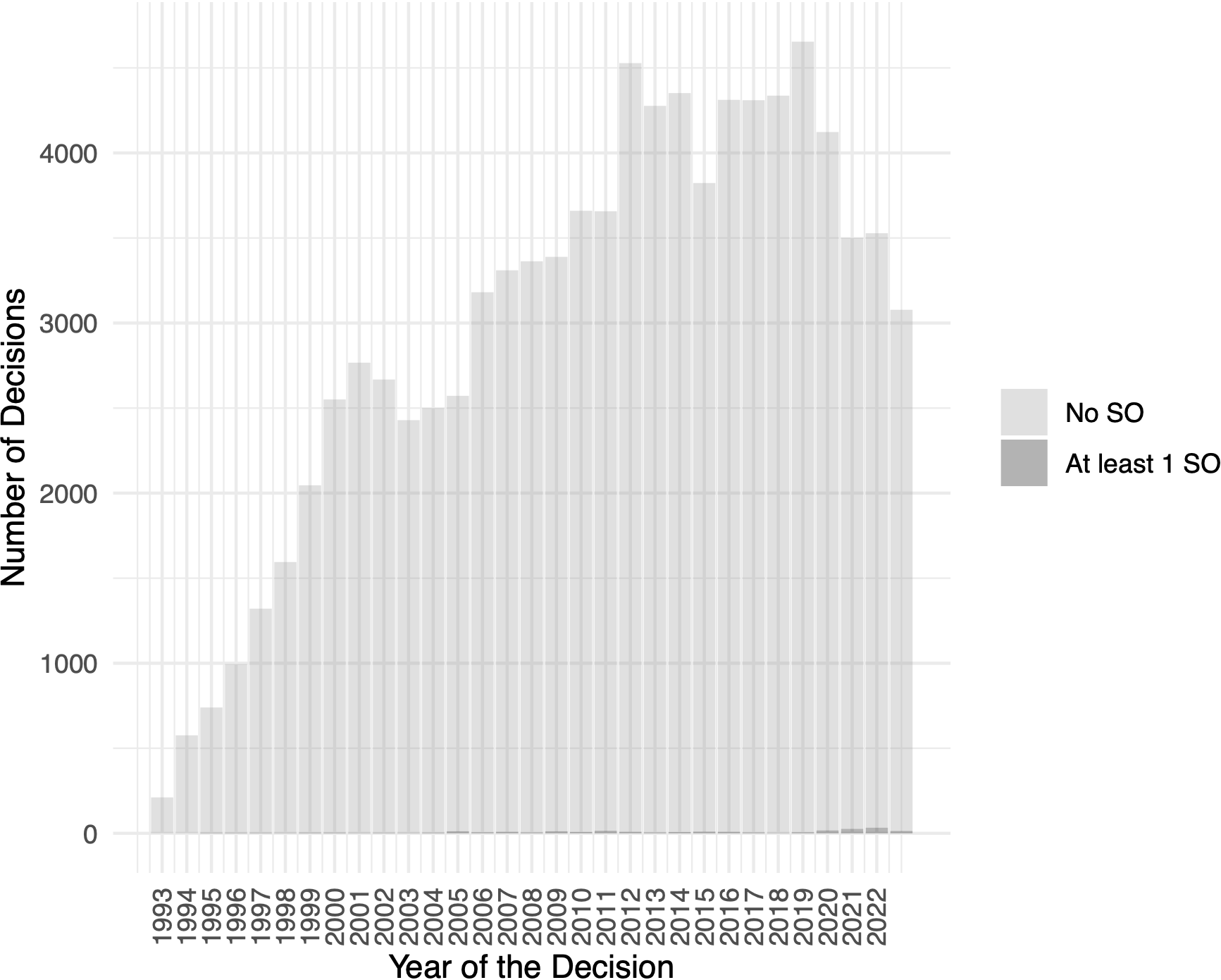

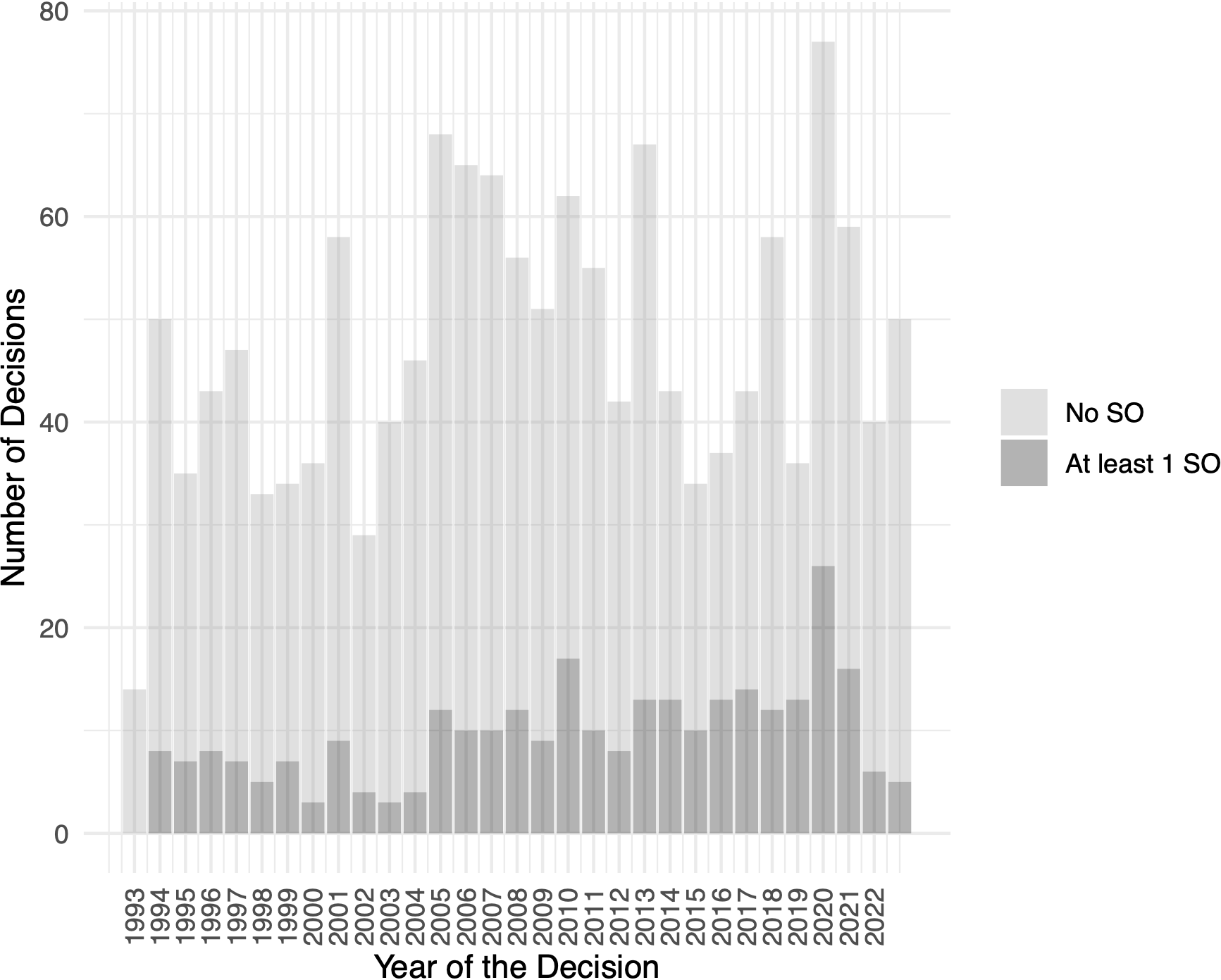

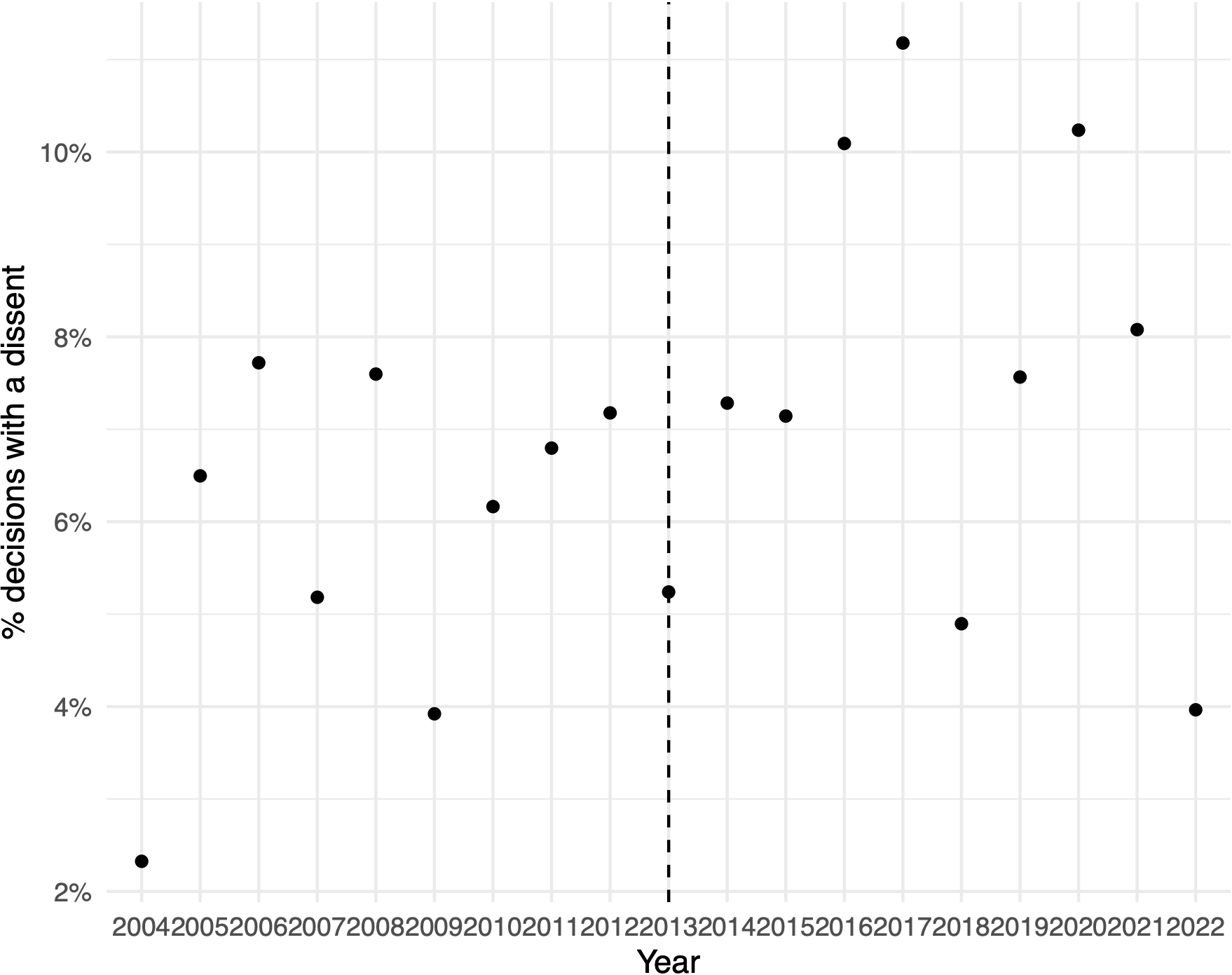

The data is based on the CCC database (Paulík 2024), which contains all decisions published by the CCC since its foundation, complete text corpus as well as plenty of metadata. The whole dataset is available at Zenodo.11 We narrow our cases to all plenum decisions and to all chamber decisions on merits up until the end of 2022. The admissibility chamber decisions must be made unanimously, separate opinions are not allowed at all, and concurring decisions are rare. Out of 87,022 chamber admissibility and procedural decisions, only 39 contain a concurring opinion.12 In contrast, out of the total 5,332 chamber decisions on merits, 201 contain at least one separate opinion. Figure 1 confirms our intuition about imbalance among the admissibility decisions. In contrast to that, the plenary decisions contain significantly larger number of separate opinions as Figure 2 shows.

Moreover, we exclude the first decade of the CCC due to incomplete and inconsistent data. For a comprehensive overview of the missing data issue, the reader can refer to Paulík (2024). For instance, very few decisions provide information about the composition of the bench, and many do not even list the names of dissenting judges. To mitigate the problem of right-censored data, we limit our analysis to decisions up to the end of 2022, as the CCC entered its fourth term in 2023 and is currently undergoing a personnel overhaul that has yet to be completed.

Figure 1. The number of the chamber decisions with at least one separate opinion (SO).

Figure 2. The number of the plenary decisions with at least one separate opinion (SO).

The final narrowed dataset for analysis contains 4,608 decisions of the CCC. Table 1 reveals that out of these, 81.2% are decisions by the chambers on merits, 9.2% are plenum decisions on merits and the remaining 9.6% are plenum decisions on admissibility. At least one separate opinion appears in 4.3% decisions out of the chamber decisions, 11.2% decisions of the plenum decisions on admissibility, and 39.4% decisions of the plenum decisions on merits. Table 8 in the Appendix shows an overview of the information on the judges that sat at the CCC in the analysed time frame.

| Table 1. Overview of the data included in the analysis. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formation | Grounds | Count | % | % with at least 1 SO |

| Chamber | Merits | 3862 | 81.2% | 4.3% |

| Plenum | Admissibility | 456 | 9.6% | 11.2% |

| Plenum | Merits | 436 | 9.2% | 39.4% |

We will now explain how we operationalized the variables in our hypotheses, beginning with the dependent variables, followed by the explanatory variables, and concluding with the control variables.

We fit two models: one for hypotheses 1–6 and one for hypothesis 7. For the former model, we conceive our dependent variable as the information whether a judge exercised a dissent in a certain decision.13 The dependent variable separate opinion is a dummy variable that has two categories: either a judge did attach a separate opinion (1) or she did not (0) in a given case.

We do not distinguish between a concurrence and a full dissent. The reason is two-fold: theoretical and practical. Theoretically, the difference between the two lays only in the disposition of the case. The judges may equally disagree on the interpretation of legal rules, thus, in the case-space model terms (Landa and Lax 2007/2008; Lax 2011), the judge cut points in any given case differ even when a judge “only” attaches a concurrence. The difference is that in the cases containing concurrence, the case facts may have accidentally fallen on the same side both of the concurring judge as well as the majority, whereas in the cases containing a dissenting opinion, the case fell in between the cut points. We do not consider this phenomenon theoretically relevant for our paper. Practically, it was impossible to distinguish between the two categories as the texts of especially the older decisions simply do not contain the information whether a separate opinion was a concurring or dissenting opinion. Attempting to impute the information by relying only on the text of the separate opinion would at best produce inaccuracy.

The dependent variable to test hypothesis 7 is also a dummy variable with two categories: (1) a separate opinion in any given case occurred or (2) did not. Unlike the previous model on the individual dissent level, the second model is on a case-level.

Disagreement potential. Based on our theory we expect the potential for disagreement to be captured by two characteristics of a case: (1) its legal complexity and (2) its controversy.

Complexity. Following the Corley, Steigerwalt, and Ward (2013) and Spriggs and Hansford (2001), our operationalization of legal complexity relies on the assumption that the more legally complex a case is, the higher the number of other laws and caselaw that the court has relied on. A case with higher legal complexity will have relied on more legal provisions or court decisions than a relatively simple case.

Practically, because the phrasing of the Czech Constitution articles is very vague, even a relatively complex case may concern just one or two articles of the Constitution. As a result, CCC decisions mostly rely on its own caselaw. Thus, we capture the complexity of a case in the variable caselaw as a number of other CCC decisions mentioned in the text of the decision.

Controversy. Certain value-laden issues may generate more disagreement even if they raise only one or few legal questions. Epstein and Segal (2000) reject all the typically employed proxies for issue salience, such as the number of articles in law review that a case generated or the number of citations a case generated. Instead, they propose a novel unbiased transparent measure of issue salience: whether a SCOTUS decision made it to the front-page of the New York Times newspaper.14 Unfortunately, practically all of the measures are hard to transfer to the Czechia context. We cannot exactly pinpoint a similar newspaper as New York Times. Therefore, we need to rely on another measure of case controversy that is already discernible at the time of the decision.

Wittig (2016) identified several particularly controversial subject matters. In the CCC context, Czech legal scholarship similarly recognizes certain issues as controversial, notably restitution cases and cases concerning fundamental human rights. The CCC database includes a subject_matter table, which specifies each case’s subject matter (e.g., discrimination or separation of powers) and its relevant constitutional area (e.g., the right to a fair trial, freedom of speech). We coded a subject matter as controversial if it involves fundamental issues of state organization or ethical matters within the Czech context. Key issues in the former category include expropriation (Radvan and Neckář 2018), restitution, state-church separation, and social rights, all sensitive topics following the transition from the Soviet regime (Bobek, Molek, and Šimíček 2009). Ethical issues, such as discrimination (Havelková 2017), same-sex marriage, transgender rights, and human dignity, have also attracted increased social attention recently. The first group primarily reflects a left-right divide, while the latter aligns with a progressive-conservative divide. The controversial dummy variable was coded as 1 for decisions involving subject matter of discrimination, expropriation, restitution, sexual orientation, fundamental human rights, social and cultural rights, property rights, freedom of speech, and state-church separation, while topics like fair trials, civil law issues, and procedural matters were coded as uncontroversial.

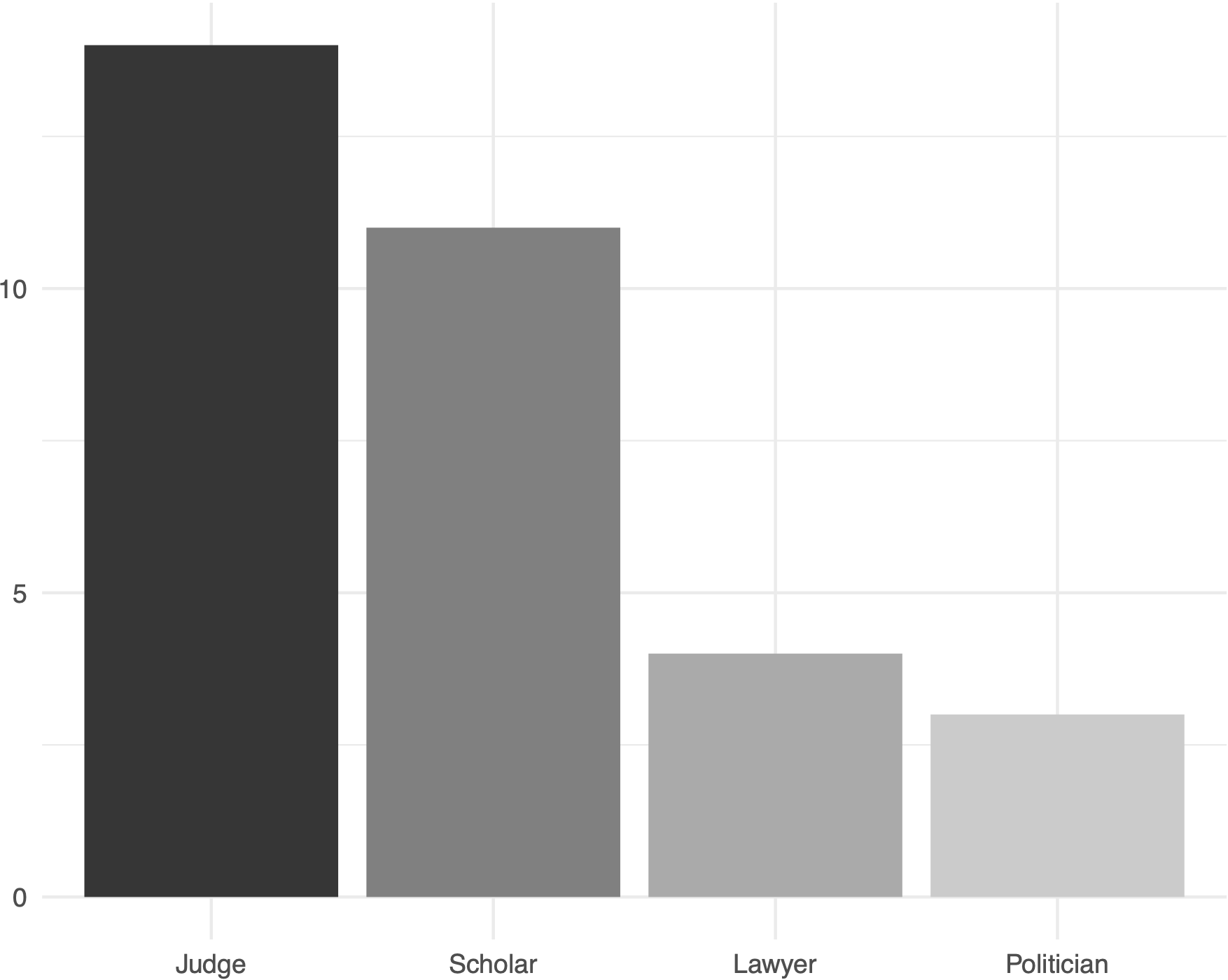

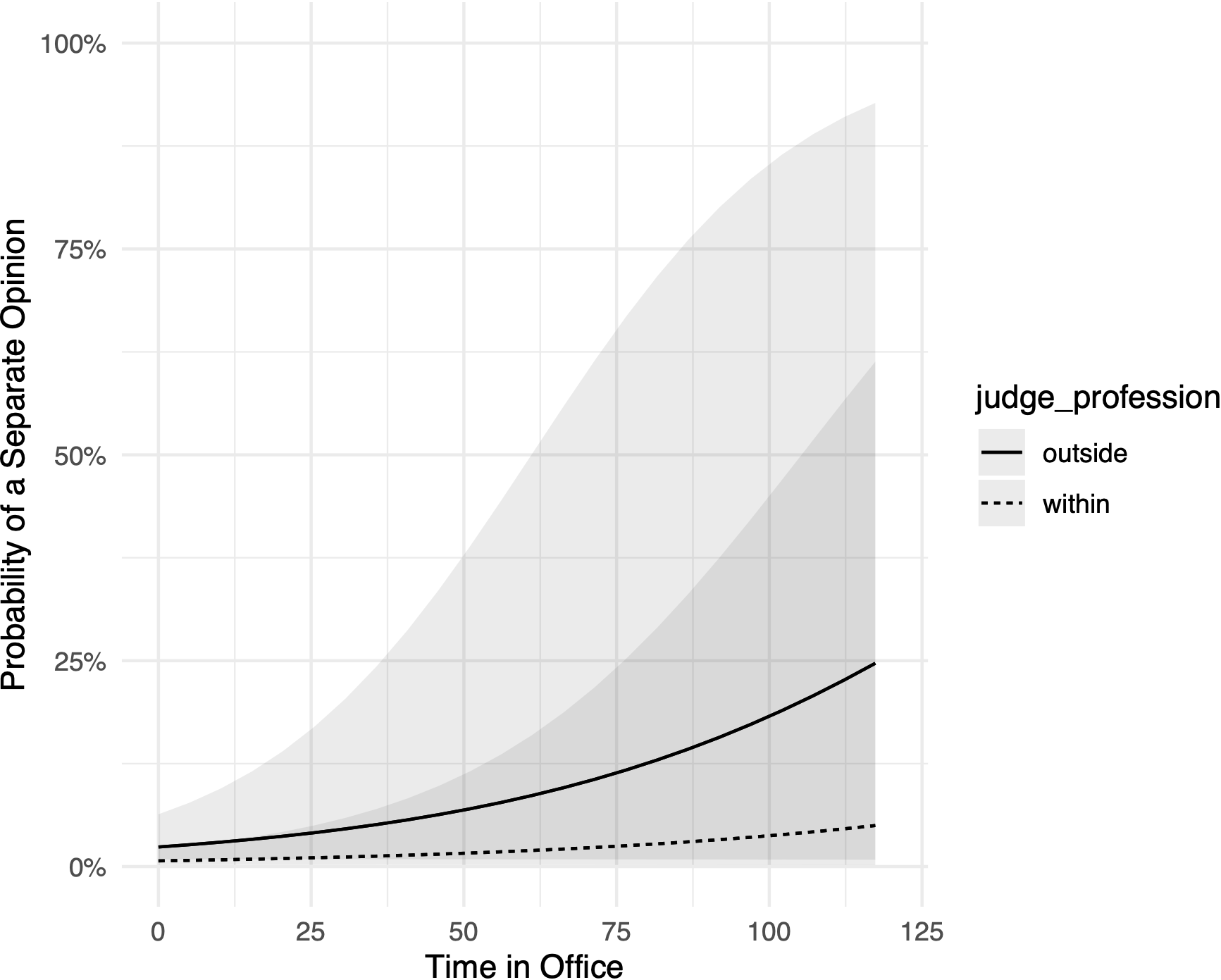

Norm-identification. We operationalize norm identification as the last profession of a judge before joining the CCC, interacted with the number of months since their appointment. In the CCC database, the variable judge_profession contains the information on the judges’ previous career choices and can take up the values of judge, scholar, politician, or lawyer. Figure 3 reveals the distribution of the professions. For our purposes, we flatten the original variable into two levels. The variable profession is coded either as “within” if the judge previously served as a judge or “outside” if they came from the other three professions. Therefore, the final dataset contains 14 judges coming out of the judiciary and 18 coming outside of the judiciary.

Figure 3. Distribution of the professions in our final dataset. Scholars, lawyers, and politicians are flattened into outside value of the profession variable.

Time in office and Time until Chamber Change. The time in office variable captures the number of months that have elapsed since the judge’s appointment. We note that since reelection is allowed and that five judges in our dataset have been re-elected once, the count does not restart with the reelection as the socialization of a reelected judge occurs from the beginning of their first mandate.

Similarly, to account for hypothesis 1 regarding collegiality, we also include the variable time until chamber change that captures the number of months until the date at which the composition of a chamber, in which the judge sits, changes divided by the total number of months spent in this chamber. In this way, we account for the 2016 introduction of the system of rotations of judges across chambers.

Workload. Similarly to the study of Brekke et al. (2023) on workload at the CJEU, we operationalize workload as the number of pending unfinished cases that a judge has in the moment of a decision. We used the information on the composition of the bench from the CCC database. We then calculated the number of unfinished cases each judge had at the time ofa decision as a judge rapporteur using the date of submission and of decision of a case. The mean number of pending cases of any judge as a judge rapporteur is 107.9, with quite a large standard deviation of 54.1. The highest number of pending cases in the dataset is 306 in the case of the judge Radovan Suchánek, whose work ethic has already become a topic of scholarly discussion (Chmel 2021).

Appointing President. To control for any potential source of bias stemming from the differing ideology of CCC judges, we also include the variable containing information on the president that appointed the judge. More specifically, we are not interested in controlling for the role of ideology for specific judges (as that gets absorbed by individual fixed effects) but rather in controlling for the dynamics within a chamber. Therefore, the variable appointing president match is coded as 1, if the appointing president of a judge in a chamber matched against that of the judge rapporteur, and 0 if they were appointed by different presidents. Because the variable would not make sense for the judge rapporteur themselves, who are also included in the analysis, the variable is interacted with the variable judge rapporteur so that we are able to obtain the estimate for the judges that were not judge rapporteurs.

Mixed coalition. Lastly, we include a dummy variable mixed coalitions, which takes up the value 1 when two conditions are met: (1) a decision was made in a chamber and (2) the composition of the chamber was made up of judges from both coalitions.

Lastly, Tables 2 and 3 present summary statistics for all dependent variables included in the models.

| Table 2. Summary statistics for the numeric dependent variables. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | Sd | P0 | P25 | P50 | P75 | P100 |

| Number of citations | 9.77 | 9.94 | 0 | 4 | 7 | 13 | 105 |

| Workload | 107.88 | 54.11 | 2 | 63 | 103 | 145 | 306 |

| Time in office | 77.16 | 55.47 | 0 | 36 | 68 | 100 | 250 |

| Time until chamber change | 48.42 | 35.21 | 0 | 17 | 42 | 79 | 119 |

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Table 4. Descriptive statistics for the fixed effects clusters. | |

|---|---|

| Variable | Count |

| Formation | |

|

199 |

|

12 |

| Year | |

|

19 |

|

1,160 |

| Judge | |

|

30 |

|

769 |

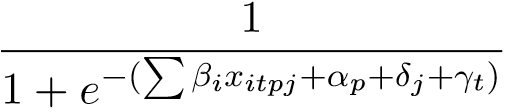

The hypotheses are tested by fitting a generalized linear model estimating the probability of a judge exercising a dissent with the dependent variable following a Bernoulli distribution. The data at hand are a time-series data with multiple sources of unobserved heterogeneity that we address by including fixed effects.

We include chamber fixed effects αc that control for time-invariant chamber-level factors. First, the different dynamics between the fifteen-member plenum and the three-member chambers could produce bias. The more controversial cases or more legally complex cases are typically assigned to the plenum and the occurrence of dissents is higher in the plenary decisions. Moreover, the behavior of the chambers varies across different chambers. Secondly, the political heterogeneity of judges is a typical source of bias in judicial behavior studies. Practically, we cannot directly estimate it using the voting behavior of judges (Segal et al. 1995), because the votes of the CCC judges are not published. We can also not we rely on the separate opinions themselves to produce point estimates of the political positions of judges, because, unlike the Hanretty (2012), a vote against the majority resolution does not necessitate a dissent and that would introduce endogeneity into our model as it would be determined and measured through the dependent variable, the dissenting behavior.

Theoretically, we are doubtful that the traditional liberal-conservative split plays that big of a role at the CCC. As explained in section 3, the CCC judges are nominated and appointed by the President of the Republic, who traditionally plays an apolitical role in the Czech political system, the CCC judges are not political candidates of Czech political parties (as in the case of the US or of Spain, Hanretty 2012). Šipulová (2018) has argued that the CCC has been relatively spared of political influence. Despite that, including chamber fixed effects should absorb any potential political heterogeneity of judges sitting in one chamber as it varies across chambers and it is assumed to be constant across time. Moreover, there may be a short overlap of judges nominated by different presidents around the year 2013. If anything, Figure 4 shows that the dissent rate slightly dipped in 2013. Because the fixed effect formation captures the exact composition of any given chamber, it should also absorb this dynamic as the mixed chambers come up as separate chambers.

Figure 4. A plot showing the development of dissent rates over time. The vertical dashed line highlights 2013, in which the CCC underwent a personal change - Miloš Zeman appointed its CCC judges.

δj judge fixed effects control for time invariant judge-level factors that are potentially correlated with both the independent as well as dependent variables of interest. For example, the judges’ philosophy may influence both their stance towards separate opinions and their career choices or the way they view controversial cases. Similarly, their ideology may influence their stance towards dissent and their view of what constitutes a controversial case. The drawback of including the judge fixed effects is that they absorb all time invariant judge-level factors (Wooldridge 2019, 463–64), including the professional background of the CCC judges. However, we are only interested in their interaction with the within-variant variable of time in office. That means that we will be able to obtain whether the difference was constant or not constant overtime (Wooldridge 2019, 465; Giesselmann and Schmidt-Catran 2022).

Lastly, we include year fixed effects γt. The included data spans two terms of the CCC. Its second decade roughly between 2003 and 2013 and its third decade between 2014 and 2023. The political and legal landscape has developed: both parliamentary (both upper and lower chambers) and presidential elections have taken place, legal reforms have been passed. Following the findings of Garoupa and Grajzl (2020), the political context may be correlated both with the willingness of the judges to dissent as well as, for example, their caseload as the political actors can lodge constitutional complaints.

Therefore, our final model is the result of the following function

Pr(separate opinion) =

, where αp are the chamber for panel p, δj are the judge fixed effects, γt are time fixed effects for year t, and the covariates in the Pβixitpj are:

β1n_references + β2profession + β3workload + β4controversial+ β5time_in_office+β6profession∗time_in_office+β7time until end+β8admissibility+ β 9appoiting_president

We also build a second model for the purpose of our fourth hypothesis. To this end, because we are interested in information on the chamber level, our unit of observation is flattened to a case leve rather than the information on dissent of each judge within a case. Our dependent variable is the information whether a separate opinion occurred or not in that decision as in the chamber decisions, the decisions have to be either made unanimously or with a two-vote majority. Our explanatory variable is the information whether the chamber was composed fully of either coalition or whether the composition was mixed. Because case assignment15 as well as the assignment of judges to chambers is as good as random, and thus there is little room for confounding, we build only a very simple logistic model with data filtered only to include chamber decisions within the third term of the CCC. The model in itself is more of a robustness check of the conclusions of Czech legal scholarship rather than a full fledged model built for causal inference.

The results are summarized in Table 5. Moving on to the interpretation of the results, our results do not support the first hypothesis. The exponentiated estimate is practically 1. The probability of a dissent does not decrease as the change of the colleagues of a judge is nearing.

Our results support the second hypothesis. Higher workload of a judge decreases their probability of attaching a separate opinion. The odds of a judge attaching a separate opinion to a decision decrease by 0.34% for each case that they have unfinished at the time of the decision. Once again, the effect is not negligible given that the mean of unfinished cases is 107.9 with a standard deviation of 54.1. The results reveal that judges of the CCC may give way to strategical considerations regarding their leisure. If they’re overburdened with work, they reduce the load elsewhere, namely in the additional burden of writing separate opinions.

Unlike at the GFCC, we do not find evidence for the norm-consensus operating according to our theoretical expectations generated by the third and fifth hypotheses. For each month that passes after a judge gets appointed, the odds of them attaching a separate opinion increase by 1.74% for the judges that had already served at a court prior to their appointment (βProfessionwithin∗Time in Office + βTime in Office) and by 2.24% for the judges a from outside the judiciary (βTime in Office), a difference that is not statistically significant. Figure 5 plots the predicted probability conditional upon the professional background and the time in the office.16 The figure reveals that although the behavior of judges with differing professional background diverges over time, the difference is insignificant. If anything, the marginal effects show that the probabilities slightly differ between the two broad categories of professional background, although it does not develop over time.17

That does not however lead us to reject the identification-disagreement as a theoretical model. We believe it to be a clear theoretical model that can guide further empirical inquiries. It may just be the case that the proxy of the judges’ profession may not be wholly accurate or that even if it was there may simply be currently no norm of consensus operating at the CCC.18

In contrast to that, we find a clear support for our fourth hypothesis and sixth hypotheses: all the disagreement potential variables are positively and significantly correlated with the likelihood of a judge attaching a separate opinion. We found a clearly statistically significant, substantive, and positive relationship between the probability of a judge attaching a separate opinion and the complexity of a case. For each further CCC decision that gets cited according to the Citations estimate, the odds of a judge attaching a separate opinion increases by 3.59%. Given that the average number of citations per decision is 9.8 with a standard deviation of 9.9, the increase is not negligible.

| Table 5. Results from the logit model. The coefficients have been exponentiated. The observation unit is the dummy of whether a judge exercised a dissent or did not within a case. | ||

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| Citations | 1.035*** | 1.036*** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| From within Judiciary | 0.298** | 0.285** |

| (0.132) | (0.133) | |

| Time in Office | 1.022+ | 1.022+ |

| (0.011) | (0.012) | |

| Time until Chamber Change | 1.009* | 1.010* |

| (0.004) | (0.005) | |

| Controversial | 1.918*** | 1.950*** |

| (0.231) | (0.253) | |

| Workload | 0.997*** | 0.997*** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Admissibility | 2.219*** | 2.156*** |

| (0.034) | (0.036) | |

| From Within Judiciary X Time in Office | 0.996** | 0.995** |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | |

| President Match 0 x Judge Rapporteur 0 | 8.317*** | |

| (4.400) | ||

| President Match 1 x Judge Rapporteur 0 | 8.049*** | |

| (3.865) | ||

| Num.Obs. | 19037 | 18976 |

| R2 | 0.166 | 0.188 |

| R2 Adj. | 0.139 | 0.160 |

| R2 Within | 0.073 | 0.096 |

| R2 Within Adj. | 0.070 | 0.093 |

| AIC | 6155.7 | 5999.1 |

| BIC | 6917.6 | 6776.3 |

| RMSE | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| Std.Errors | by: formation | by: formation |

| FE: year_decision | X | X |

| FE: formation | X | X |

| FE: judge_name | X | X |

Figure 5. Predicted probability of a separate opinion occurring conditional on the previous profession of a judge and the number of months that has elapsed since their appointment. Most of the background is gray due to the size of the standard errors, which overlap with each other.

The same applies to the controversial value-laden topics. The odds of a judge attaching a separate opinion increases by 95.01% in decisions concerning a controversial topic in comparison to uncontroversial cases all other variables being held fixed. Because we are aware of the potential issue with “arbitrarily” selecting a couple of potential subject matters, we decided to test the robustness of our controversial variable. To do so, we conducted a placebo test. We sampled ten placebo samples of thirteen different subject matters and fitted a model with the same dependent and independent variables, with the same fixed effects, the only difference being the controversial variable replaced by the placebo. Heeding the Hartman and Hidalgo (2018) paper on placebo tests, we than run an equivalence test with the following hypotheses:

H0Equivalence : βcontroversial − 0.36SEβcontroversial < βplacebo < βcontroversial + 0.36SEβcontroversial

H0Non−Superiority : βplacebo ≥ βcontroversial + 0.36Seβcontroversial

H0Non−Inferiority : βplacebo ≤ βcontroversial − 0.36SEβcontroversial

We run the placebo test ten times, Table 6 displays the result. None of the placebo effects passed the equivalence test, i.e. the null hypothesis of the effect of the placebo falling within the equivalence range set by the H0 may be rejected. Moreover, all the placebo test fail to reject the test of noninferiority, i.e. we can reasonably conclude that the effects of the placebo are significantly lower than of the βcontroversial.

| Table 6. The result of ten models fitted with different placebo sample from the subject matter variable. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | P(non-zero) | P(equivalence) | P(non-superiority) | P(non-inferiority) | |

| Placebo1 | 0.31 | 0.54 | 0.73 | 0.22 | 0.73 |

| Placebo2 | 0.04 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.05 | 0.93 |

| Placebo3 | -0.11 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.10 | 0.87 |

| Placebo4 | 0.69 | 0.03 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.41 |

| Placebo5 | 0.16 | 0.65 | 0.90 | 0.06 | 0.90 |

| Placebo6 | 0.49 | 0.05 | 0.70 | 0.18 | 0.70 |

| Placebo7 | -0.14 | 0.72 | 0.98 | 0.01 | 0.98 |

| Placebo8 | 0.05 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.04 | 0.93 |

| Placebo9 | -0.40 | 0.32 | 0.99 | 0.00 | 0.99 |

| Placebo10 | 0.06 | 0.87 | 0.92 | 0.05 | 0.92 |

| Note: The models have been fitted under the same specification as the full model, we are only including the estimates for the placebo variable for the sake of clarity. | |||||

To test the robustness of our results against judges’ ideology, we included an interaction term between the appointing president match and judge rapporteur variables. The results of the model (2) in 5 remain robust against the inclusion of the interaction term.

In line with our seventh hypothesis based on the theoretical expectations generated by the Czech legal scholarship as well as the disagreement potential, we find that a separate opinion is more likely to occur in the chamber cases, whose composition is mixed by members of both voting blocs from the plenary proceedings. Table 7 reveals that the size of the effect is not negligible. The odds of a separate opinion occurring increase by 277.61%. While we are aware that our model is not thorough enough for any causal inference, it is rather a form of robustness check to the Czech legal scholarship that we summarized in the theoretical section.

We attach an important disclaimer. With these results, we do not pretend to make causal claims about the features of the CCC. Although we have tried our best to control for as many potential sources of bias, our study nonetheless relies on observational data and the proxy variables we have employed are far from perfectly capturing the underlying feature. Despite that we believe to have contributed to the empirical legal research on dissenting behavior. We have shed some light into the functioning of the CCC, which so far has not been a subject of thorough empirical research.

Due to its similarity with other courts, our results are not necessarily idiosyncratic to the CCC.

| Table 7. Results from the Logit Model on Coalitions. | |

|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.019*** |

| (0.006) | |

| Mixed Composition | 3.776*** |

| (1.248) | |

| Num.Obs.w | 1579 |

| R2 | 0.035 |

| R2 Adj. | 0.031 |

| AIC | 592.2 |

| BIC | 603.0 |

| RMSE | 0.21 |

| Std.Errors | IID |

| Note: The observation unit is the dummy of whether a dissent occurred in a case or not. | |

We examined the factors influencing dissenting opinions by judges at the CCC. Our findings do not support the existence of a strong norm of consensus at the CCC, unlike at the GFCC. However, the complexity of a case is positively correlated with the probability of a dissenting opinion. Similarly, cases concerning controversial topics are more likely to generate dissents. A placebo test strengthens this finding by demonstrating that randomly chosen, non-controversial topics have minimal impact on dissenting behavior. The effect of voting blocs in the plenary proceedings seems to carry over to the chamber proceedings. The results also reveal that judges make strategic considerations. When facing a high workload, judges are less likely to write separate opinions, suggesting that they prioritize workload management. Lastly, CCC judges do not seem to take into account collegiality costs.

To conclude, we set our findings in the broader debate on dissenting opinions in civil law legal systems presented mainly by Kelemen (2017). First, our finding that there is no strong norm of consensus at the CCC contrasts with Kelemen’s theoretical observation as well as with Wittig (2016) empirical finding of a culture of consensus in the GFCC, where judges prefer to reach an agreement and write separately only in exceptional circumstances (Kelemen 2017, 87). This suggests that the strength of the norm of consensus may vary across civil law legal systems and that further research is needed to understand the factors that influence its development.

Second, our paper’s findings regarding the impact of case complexity and controversial topics on dissenting opinions support Kelemen’s argument that judges are more likely to exercise dissent in cases of particular public or political interest (Kelemen 2017, 88). This highlights the importance of considering the context of a case, which is no easy feat.

Third, the paper’s finding that CCC judges make strategic considerations, such as prioritizing workload management, when deciding whether to write a separate opinion, is consistent with the observations of (Wittig 2016). As Kelemen (2017) notes however, it is difficult to pinpoint the extent of the influence exactly due to the sheer complexity of this “personal dimension”19 of dissenting behavior as well as the insufficient data on judicial decision-making within civil law courts in general.

To conclude, we believe that the focus of our paper on a civil law legal system provides valuable empirical evidence to contrast with the existing literature on dissenting opinions, which is largely dominated by studies on common law systems.

Arel-Bundock, Vincent, Noah Greifer, and Andrew Heiss. “How to Intepret Statistical Models Using Marginaleffects for R and Python.” Journal of Statistical Software.

Bobek, Michal, Pavel Molek, and Vojtěch Šimíček. 2009. Komunistické Právo v Československu : Kapitoly z dějin Bezpráví. Brno: Masarykova univerzita Brno, Mezinárodní politologický ústav.

Brekke, Stein Arne, Daniel Naurin, Urška Šadl, and Lucía López-Zurita. 2023. “That’s an Order! How the Quest for Efficiency Is Transforming Judicial Cooperation in Europe.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 61 (1): 58–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13346.

Bricker, Benjamin. 2017. “Breaking the Principle of Secrecy: An Examination of Judicial Dissent in the European Constitutional Courts.” Law & Policy 39 (2): 170–91. https://doi.org/10. 1111/lapo.12072.

Calderia, Gregory A., and Christopher J. W. Zorn. 1998. “Of Time and Consensual Norms in the Supreme Court.” American Journal of Political Science 42 (3): 874–902. https://doi.org/10. 2307/2991733.

Chmel, Jan. 2017. “Zpravodajové a Senáty: Vliv Složení Senátu Na Rozhodování Ústavního Soudu České Republiky o Ústavních Stížnostech.” Časopis Pro Právní vědu a Praxi 25 (4): 739. https://doi.org/10.5817/CPVP2017-4-9.

Chmel, Jan. 2021. Co Ovlivňuje Ústavní Soud a Jeho Soudce? /. Vydání první. Teoretik (Leges).

Clark, Tom S., Benjamin G. Engst, and Jeffrey K. Staton. 2018. “Estimating the Effect of Leisure on Judicial Performance.” The Journal of Legal Studies 47 (2): 349–90. https://doi.org/10. 1086/699150.

Corley, Pamela C., Amy Steigerwalt, and Artemus Ward. 2013. The Puzzle of Unanimity: Consensus on the United States Supreme Court. Redwood City: Stanford University Press.

Engel, Christoph, and Keren Weinshall. 2020. “Manna from Heaven for Judges: Judges’ Reaction to a Quasi-Random Reduction in Caseload.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 17 (4): 722–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/jels.12265.

Epstein, Lee, and Jack Knight. 2000. “Toward a Strategic Revolution in Judicial Politics: A Look Back, A Look Ahead.” Political Research Quarterly 53 (3): 625–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 106591290005300309.

Epstein, Lee, William M. Landes, and Richard A. Posner. 2011. “Why (and When) Judges Dissent: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis.” Journal of Legal Analysis 3 (1): 101–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/jla/3.1.101.

Epstein, Lee, and Jeffrey A. Segal. 2000. “Measuring Issue Salience.” American Journal of Political Science 44 (1): 66–83. https://doi.org/10.2307/2669293.

Garoupa, Nuno, and Peter Grajzl. 2020. “Spurred by Legal Tradition or Contextual Politics? Lessons about Judicial Dissent from Slovenia and Croatia.” International Review of Law and Economics 63 (September): 105912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irle.2020.105912.

Garoupa, Nuno, Laura Salamero-Teixidó, and Adrián Segura. 2022. “Disagreeing in Private or Dissenting in Public: An Empirical Exploration of Possible Motivations.” European Journal of Law and Economics 53 (2): 147–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-021-09713-6.

Giesselmann, Marco, and Alexander W. Schmidt-Catran. 2022. “Interactions in Fixed Effects Regression Models.” Sociological Methods & Research 51 (3): 1100–1127. https://doi.org/10. 1177/0049124120914934.

Hanretty, Chris. 2012. “Dissent in Iberia: The Ideal Points of Justices on the Spanish and Portuguese Constitutional Tribunals.” European Journal of Political Research 51 (5): 671–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2012.02056.x.

Hanretty, Chris. 2013. “The Decisions and Ideal Points of British Law Lords.” British Journal of Political Science 43 (3): 703–16. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123412000270.

Hanretty, Chris. 2015. “Judicial Disagreement Need Not Be Political: Dissent on the Estonian Supreme Court.” Europe-Asia Studies 67 (6): 970–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2015.1054260.

Hartman, Erin, and F. Daniel Hidalgo. 2018. “An Equivalence Approach to Balance and Placebo Tests.” American Journal of Political Science 62 (4): 1000–1013. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps. 12387.

Havelková, Barbara. 2017. Gender Equality in Law: Uncovering the Legacies of Czech State Socialism. Oxford ; Portland, Oregon: Hart Publishing.

Hořeňovský, Jan, and Jan Chmel. 2015. “The Process of making the Constitutional Court Judgements.” Časopis pro právní vědu a praxi 23 (3): 302–11.

Kelemen, Katalin. 2017. Judicial Dissent in European Constitutional Courts: A Comparative and Legal Perspective. Routledge.

Kosař, David, and Ladislav Vyhnánek. 2020. “The Constitutional Court of Czechia.” In The Max Planck Handbooks in European Public Law: Volume III: Constitutional Adjudication: Institutions, edited by Armin von Bogdandy, Peter Huber, and Christoph Grabenwarter, 0. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198726418.003.0004.

Landa, Dimitri, and Jeffrey R. Lax. 2007/2008. “Disagreements on Collegial Courts: A Case-Space Approach.” University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law 10 (2007/2008): 305.

Lax, Jeffrey R. 2011. “The New Judicial Politics of Legal Doctrine.” Annual Review of Political Science 14 (1): 131–57. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.042108.134842.

Martin, Andrew D., and Kevin M. Quinn. 2002. “Dynamic Ideal Point Estimation via Markov Chain Monte Carlo for the U.S. Supreme Court, 1953–1999.” Political Analysis 10 (2): 134–53. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/10.2.134.

Narayan, Paresh Kumar, and Russell Smyth. 2005. “The Consensual Norm on the High Court of Australia: 1904-2001.” International Political Science Review 26 (2): 147–68. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/0192512105050379.

Paulík, Štěpán. 2024. “The Czech Constitutional Court Database.” Journal of Law and Courts Forthcoming.

Radvan, Michal, and Jan Neckář. 2018. “Expropriation from the Wider Perspective in the Czech Republic.” In Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Issues in Expropriation. Routledge.

Segal, Jeffrey A., Lee Epstein, Charles M. Cameron, and Harold J. Spaeth. 1995. “Ideological Values and the Votes of U.S. Supreme Court Justices Revisited.” The Journal of Politics 57 (3): 812–23. https://doi.org/10.2307/2960194.

Šipulová, Katarína. 2018. “The Czech Constitutional Court: Far Away from Political Influence.” In Constitutional Politics and the Judiciary. Routledge.

Smekal, Hubert, Jaroslav Benák, Monika Hanych, Ladislav Vyhnánek, and Štěpán Janků. 2021. Mimoprávní Vlivy Na Rozhodování Českého Ústavního Soudu: Brno: Masaryk University Press. https://doi.org/10.5817/CZ.MUNI.M210-9884-2021.

Songer, Donald R., John Szmer, and Susan W. Johnson. 2011. “Explaining Dissent on the Supreme Court of Canada.” Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue Canadienne de Science Politique 44 (2): 389–409. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423911000151.

Spriggs, James F., and Thomas G. Hansford. 2001. “Explaining the Overruling of U.S. Supreme Court Precedent.” The Journal of Politics 63 (4): 1091–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/00223816.00102.

Varol, Ozan O., Lucia Dalla Pellegrina, and Nuno Garoupa. 2017. “An Empirical Analysis of Judicial Transformation in Turkey.” The American Journal of Comparative Law 65 (1): 187– 216. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcl/avx013.

Vartazaryan, Gor. 2022. “Sít’ová Analy`za Disentujících Ústavních Soudců.” Pravnik, no. 12.

Vartazaryan, Gor, and Štěpán Paulík. 2024. “’I Have Spoken and Saved My Soul’: A Qualitative Analysis of Dissenting Behavior of Czech Constitutional Judges”. Working Paper. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.26831.09124.

Wittig, Caroline. 2016. The Occurrence of Separate Opinions at the Federal Constitutional Court. Logos Verlag Berlin. https://doi.org/10.30819/4411.

Wooldridge, Jeffrey M. 2019. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach. Cengage Learning.

Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, stepan.paulik.1@hu-berlin.de or stepanpaulik@gmail.com, https://orcid.org/0009-0007-6424-5209.↩︎

Charles University, gorike2000@gmail.com, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0367-7274.↩︎

We use the term dissent for both a separate and a concurring opinion.↩︎

Notably, in the Melčák case, the CCC entered a highly charged political arena by annulling a constitutional amendment that shortened the term of the Chamber of Deputies, sparking a prolonged constitutional crisis. The English version of the decision is available at: https://www.usoud.cz/en/decisions/2009-09-10-pl-us-27-09constitutional-act-on-shortening-the-term-of-office-of-the-chamber-of-deputies.↩︎

As explained below, nearly all judges of a given term have been nominated and appointed by the same President and Senate.↩︎

We conducted interviews with judges from the third term of the CCC, and nearly all of them confirmed, to varying degrees, that they believe judges should not display dissent in a civil law court.↩︎

And therein they are an extreme oddity too.↩︎

Technically, something resembling a dissenting opinion can be included in the voting record in criminal cases. However, it remains contentious whether we should speak of dissent, as Article 58 of the Code of Criminal Procedure allows dissenting opinions from the majority view to be recorded at any level, though this record is always kept confidential from participants and serves solely as a basis for potential review by a higher court. This confidentiality prevents it from constituting true dissent, particularly due to its lack of public accessibility.↩︎

From now on we omit the three-member for readability reasons. Whenever we speak of only of chambers, we refer to the three member chambers.↩︎

Which makes it difficult to, for example, conduct the same point-estimation with data on dissenting behavior of judges as Hanretty (2012) has done on the Portuguese and Spanish Constitutional Courts.↩︎

On top of that out of the 39 concurring opinions in admissibility chamber decisions, 25 of that are a copy-pasta from judge Jan Filip and 6 are a copypasta from judge Josef Fiala. In other words, judge Jan Filip copied and pasted literally the same concurring opinion in a group of cases concerning impartiality of one of the other judges in his chamber. The same applies for Josef Fiala.↩︎

Unlike Wittig (2016) or Varol, Dalla Pellegrina, and Garoupa (2017) we do not call our dependent variable a judge’s vote, as that refers to a slightly different thing within the CCC context. A judge may vote against the majority opinion but since they are not mandated to write a separate opinion, these do not necessarily overlap. Similarly, a judge may vote for a disposition of a case and still attach a concurrence separate opinion.↩︎

The question is to what extent does that not also reflect the retrospective issue salience.↩︎

The cases are assigned randomly to judges rapporteur based on the first letter of their surname.↩︎

Implemented using the R package Marginal Effects (Arel-Bundock, Greifer, and Heiss, Forthcoming).↩︎

The inclusion of judge FE does not allow us to estimate the effect of professional background directly as it is invariant within individual judges.↩︎

We have conducted interviews with the CCC judges and they have revealed exactly that: there is little to none agreement as to the role and perception of the CCC.↩︎

For example, semi-structured interviews with the CCC judges revealed that they also let their decisions be guided by emotions they experience during the decision-making process, a phenomenon that we have not seen researched very in depth Vartazaryan and Paulík (2024).↩︎