Sandeep Bhupatiraju, Daniel L. Chen,

Shareen Joshi and Peter Neis§

Introduction

A lot rides on a person’s name. When printed on top of a resume,

application form or petition in an institutional setting, a name can

provide clues about an applicant’s gender, race, religion, ethnicity,

and socioeconomic background. This can become the basis of

discrimination (Small and Pager 2020). In the United States, names that

appear to be distinctively black have been associated with higher

mortality (Cook, Logan, and Parman 2016), fewer responses to job-search

applications (Bertrand and Mullainathan 2004), and less mentorship in

educational institutions (Milkman, Akinola, and Chugh 2012). In Germany,

unpopular or ”negative” names are associated with neglect in online

dating platforms, low achievement, and weak self-esteem (Gebauer, Leary,

and Neberich 2012).

Names can be even more powerful in post-colonial societies with

strong traditional institutions. In India, names often reveal religion,

birthplace, and inherited caste (Das and Copeman 2015; Hoff and Pandey

2006; Banerjee et al. 2009; Gidla 2017; Parmar 2020).

These names function as crucial identifiers within paper-heavy

bureaucratic systems, profoundly influencing how state institutions

interact with and serve individuals (Hull 2012; Steinberg 2015).

Constitutional prohibitions on identity-based discrimination have not

fully curbed the tendency of people to scrutinize names for markers of

their origins (Deshpande 2011). Names affect call-back rates for jobs

(Banerjee et al. 2009; Thorat and Attewell 2007), the outcomes of job

interviews (Deshpande and Newman 2007), loan approvals (Fisman,

Paravisini, and Vig 2017), purchasing behavior (Mazzarella 2015), and

even children’s cooperative behavior (Hoff and Pandey 2006; Hoff,

Kshetramade, and Fehr 2011).

Widespread concerns about name-based discrimination have spurred

efforts to modify or conceal names. In the U.S., immigrants often adopt

non-ethnic names for their children to aid assimilation (Abramitzky,

Boustan, and Eriksson 2020). Organizations increasingly use algorithms

to screen resumes, aiming to eliminate human biases (Rambachan et al.

2020). In parts of India, a significant movement after independence led

many Indians to adopt caste-neutral names to mitigate historical

inequalities (Jayaraman 2005; Parmar 2020; Das and Copeman 2015). Some of India’s most famous

celebrities have changed their names.

In certain regions, such as Bihar – the focus of this paper – name

“doubling” is now widespread, i.e. a citizen adopts a “caste-neutral”

surname (also known as last names or family names, henceforth just

“names”) for school, work and official settings, but retains a

traditional name for personal interaction or to access certain state

schemes (Das and Copeman 2015). Name doubling is particularly common

among vulnerable communities (Mazzarella 2015; Parmar 2020).

In this study we explore the influence of names, particularly

caste-neutral names, in recent cases at the Patna High Court (2009–2019)

on the outcomes of justice. Bihar, with its population exceeding 100

million, is an ideal setting for this study – it is a large and

predominantly rural state that is deeply stratified along caste and

religious lines (Joshi, Kochhar, and Rao 2022; Chakrabarti 2013; Kumar

2018). Official names are the sole visible marker of a person’s

identity in legal settings (Chen, Moskowitz, and Shue 2016; Berdejo and

Chen 2017). This creates a compelling context for examining the

relationship between names and judicial outcomes.

Our study examines name distribution in the Patna High Court,

comparing it to other state institutions. Using machine learning, we

infer caste, religion, and gender from names in our legal data. We

categorize Hindu names into three groups: caste-neutral, Scheduled

Castes (SC), and other caste-indicative names. We analyze caste-neutral

and SC names together as potentially ‘low-status’, while also comparing

them separately. This approach allows us to investigate differences in

legal outcomes and evaluate the effectiveness of caste concealment and

lawyer-judge matching strategies.

Our analysis reveals minimal judge-litigant matching based on

name-derived identity measures. However, we observe significant matching

between litigants and advocates. Notably, petitioners with caste-neutral

names are 3 percentage points (pp) more likely to select low-status

advocates compared to high-caste petitioners. Interestingly, this

pattern is entirely absent among low-caste petitioners whose names

indicate their caste status.

We also see that name-based matching can have modest but yet

noticeable impacts on both judicial processes and outcomes. Low-status

petitioners matched with low-status judges face subtle but significant

disadvantages, including a 1.1 pp increase in dismissal rates and a 0.7

pp decrease in successful cases. These disadvantages are primarily

concentrated among caste-neutral petitioners. Advocates, regardless of

caste classification, do not appear to face any significant differences

in outcomes on the basis of their names. However, low-status petitioners

with low-status advocates are 0.7 pp less likely to have their case

allowed, while low-status respondents with low-status advocates are 4.5

pp more likely to have their case dismissed, with these effects mainly

observed in caste-neutral groups.

Our study reveals that using caste-neutral names in India’s courts is

a double-edged sword. While it may offer some protection against overt

bias, it also prevents litigants from receiving necessary

accommodations. This strategy fails to improve judicial outcomes and may

inadvertently reinforce the social hierarchies it aims to overcome,

highlighting the persistence of caste-based inequalities in the legal

system.

The rest of our paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides an

overview of the context, Section 3 provides an overview of data, Section

4 gives an overview of the names and their concentration in the data,

Section 5 gives a summary over identities of petitioners, respondents

and judges at the Patna HC, Section 6 analyses matching between judicial

actors, Section 7 studies how judicial actor's identities and matching

between them are related to case outcomes, Section 8 provides a

discussion and the final section concludes.

Context: Politics, Society and

Justice in Bihar

Bihar, one of India’s historically poorest states, has long grappled

with lawlessness, caste violence, and underdevelopment. These issues,

rooted in colonial land systems, have profoundly shaped the state's

social hierarchy and justice system, underscoring the significance of

name-changing practices in this context.

Caste

Hindus account for 82% of Bihar’s population (Verma 2023). Hindus are

organized in broad caste categories such as Forward Caste (FC),

Scheduled Caste (SC) and Scheduled Tribe (ST). In

everyday life however, identity is experienced and practiced as jāti

(henceforth, jati) (Bayly 2001; Jodhka 2017). These are hereditarily

formed endogamous groups with distinctive practices that include (but

are not limited to) naming conventions, occupations, property ownership,

diet, gender norms, and religious rituals. Bihar has hundreds of jatis,

with complex placement in official categories and significant inter- and

intra-level inequality (Joshi, Kochhar, and Rao 2022).

The placement of castes in an official hierarchy began in the

colonial period when British used caste as an official identity marker

that determined eligibility for recruitment into the army and

bureaucracy (Dirks 1989; Bayly 2001). Post-independence, India's

Constitution addressed caste inequality: Article 14 guarantees equality

and prohibits discrimination, while Articles 15(4) and 16(4) allow for

special provisions for backward classes, enabling reservations in

education and public employment for SC, ST, and OBCs.

Despite these provisions, caste continues to characterize the social

structure of the state. FCs at the top includes jatis such as Brahmins,

Rajputs, Bhumihars, and Kayasthas and accounts for about 15–20% of the

population (Kumar 2018; Verma 2023). These groups have

wielded significant power in the aftermath of colonial rule (Diwakar

1959). Recent evidence suggests that they

are about twice as likely to be literate and hold land than their

lower-status counterparts (Joshi, Kochhar, and Rao 2018). They also have

the highest levels of income and asset ownership than any other

caste-group (Tewary 2023).

Bihar’s “backward classes” comprise a significant portion of the

population. SCs make up 19.7% while other categories include OBC, BC,

and EBC, with OBCs accounting for 27.1% (Verma 2023; Tewary 2023). Scheduled Tribes now represent only

1.7% of Bihar's population, as most tribal areas are now part of

Jharkhand.

Power struggles between caste groups have frequently driven

instability in Bihar (Jaffrelot and Kumar 2012). The 1980s saw private

caste armies (Chakrabarti 2013). In the 1990s, law and order

deteriorated, and development policies were caste-centric. Until

recently, Bihar has lacked the pan-state identity that has been seen

elsewhere (Singh 2015).

These pressures, however, while eroding law and order and stifling

development in the state, have also contributed to the emergence of some

of the most ambitious affirmative action policies in India (Blair 1980;

Kumar 2018). In 1977, the first non-INC government instituted policies

that reserved 20 percent of public sector jobs for OBCs (Chakrabarti

2013). This group includes jatis such as

Bania, Yadav, Kurmi, and Koiri – all agrarian communities that have

acquired land, adopted improved agricultural technology (Kumar 2018).

The group now wields considerable political power in the state

(Jaffrelot and Kumar 2012).

Caste and religion continue to be salient forms of identity in Bihar.

The complex interplay between entrenched social hierarchies and

aspirations for a more egalitarian society has contributed to the

emergence of name “doubling” among Bihar's citizens. Though this

practice has received little academic analysis, it remains an

established convention in many communities in India (Jayaraman 2005; Das

and Copeman 2015; Buswala 2023). With districts

consisting of approximately 4 million people, individuals and

communities can generally use their official names in official settings

and their given names in personal settings throughout their lives.

Justice System

The Patna High Court is about 100 years old. It was first established

by the British in 1912 and began hearing cases in 1916, with a Chief

Justice and six other judges. There are currently 22 permanent judges,

including the Chief Justice and 14 additional judges. Bihar has sent

more justices to the Supreme Court than any other Indian state

(Chandrachud 2020).

Prior research on the Indian justice system has argued that the

system’s colonial roots continue to influence the courts in a variety of

ways. Colonial courts were designed by colonial administrators and

sought to secure Indian subjecthood rather than serve citizens (Menski

2006). After India’s independence, the development of the Patna High

Court has been constrained by weaknesses of state capacity, caste-based

conflict and the episodic violence in the state (Chakrabarti 2013;

Jaffrelot 2010; Kumar 2018). Political battles, often accompanied by

complex allegations of corruption and criminality, have often found

themselves being decided in the Patna High Court, straining the court’s

political neutrality (Roy 1997). In recent years, however, the

challenges of the Patna High Court largely align with those of the

Indian justice system more broadly (Sen 2017).

Data

Patna High Court Cases

Our dataset comprises of 1,071,068 judgements which correspond to

986,024 unique cases heard at the Patna High Court from 2009–2019,

scraped from public records. We gather data on case attributes (type of

case, lawyer, etc.) as well as auxiliary data from police stations,

district courts, and judge biographies. The dataset consists of 360,432

(34%) civil cases and the remainder are criminal cases.

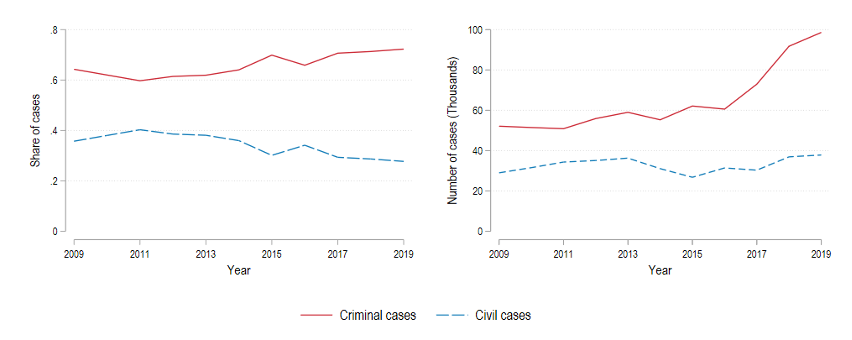

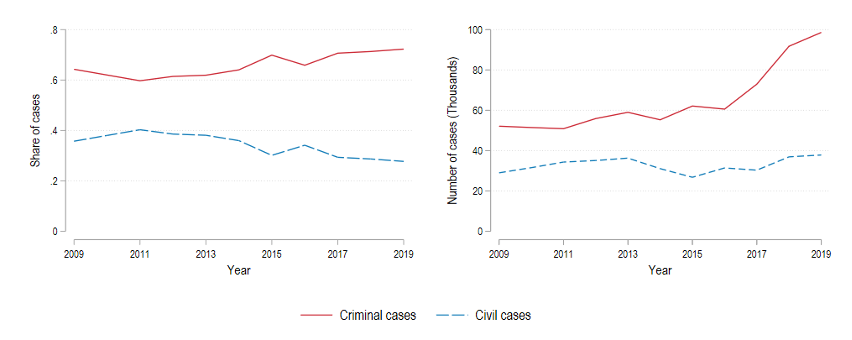

Figure 1 shows case trends, with criminal cases rising since 2015.

This increase likely stems from the controversial Bihar Prohibition law,

implemented in 2015, briefly overturned, then reinstated (Dar and Sahay

2018). Reportedly, over 200,000 people have been charged under this act,

with 50,000+ bail applications pending at the Patna High Court.

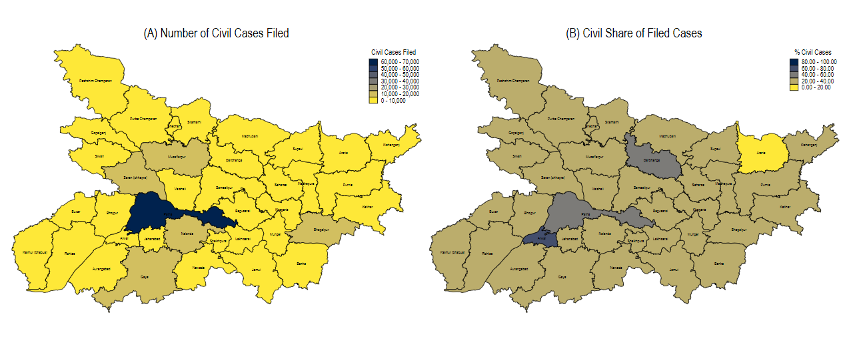

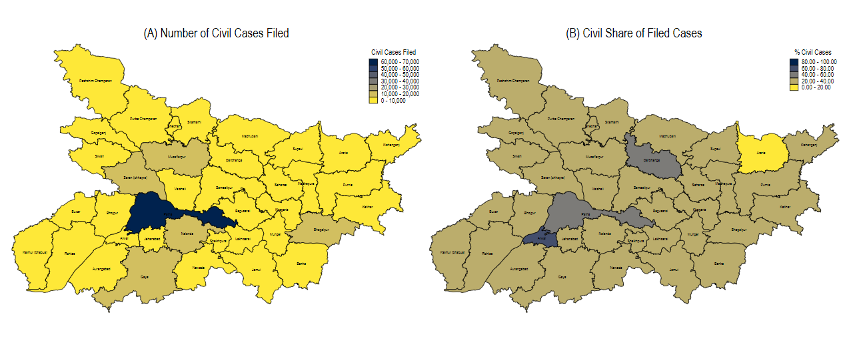

Figure 2 displays the spatial variation of civil cases (Panel A) and

the share of civil cases of all filed cases (Panel B) across Bihar's

districts. While the district of Patna strikes out as having by far the

highest number of civil filings, there is much less spatial

heterogeneity in the share of civil cases.

Figure 1.

Time Trends of Criminal and Civil Cases Filed at the Patna High Court,

2009-2019. The figure depicts time trends of the number (Panel A) and

share (Panel B) of civil and criminal cases filed per year in the Patna

High Court between 2009 and 2019. Calculations are based on the full

sample of 1,071,068 cases filed in this time period.

Figure 1.

Time Trends of Criminal and Civil Cases Filed at the Patna High Court,

2009-2019. The figure depicts time trends of the number (Panel A) and

share (Panel B) of civil and criminal cases filed per year in the Patna

High Court between 2009 and 2019. Calculations are based on the full

sample of 1,071,068 cases filed in this time period.

Figure 2. Spatial Distribution of Civil cases filed

at the Patna High Court, 2009-2019. Panel (A) displays the total number

of civil cases filed per district in the Patna High Court between 2009

and 2019. Panel (B) plots the share of cases filed per district which

are civil cases.

Additional Data on Names

For the purpose of comparing the courts to other institutions in

Bihar, we supplement the judicial data with additional data from several

public sources:

Socio-economic Caste Census (SECC) for Bihar: The

SECC data has not been officially released by the Government of India.

We rely on the replication files of existing research to access these

data (Sood and Laohaprapanon 2018).

Registered Farmers: We use a database of about 1.3

million registered farmers from the Bihar Cooperative Department. We have no information on the

criteria that were used to include farmers in this database. It is quite

likely, however, that the most well-connected and well-placed farmers

were able to register and take loans in the early stages of this

registration effort. This, however, makes the dataset particularly

well-suited to understand who benefits from agrarian policies in

Bihar.

Government Employees: We draw on a database of

210,389 employees of the Bihar state-government who have officially

disclosed their financial status to comply with policies of the

Government of India.

|

N

|

Woman |

Muslim |

SC

|

ST

|

Other Hindu |

Patna State Sources

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Farmers

|

1,341,181 |

27.62

|

6.17

|

10.28 |

1.05 |

82.74

|

Government Employees

|

210,389

|

29.01

|

9.35

|

13.28 |

1.67 |

76.00

|

Patna HC

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Judges

|

83

|

9.64

|

6.02

|

6.41

|

1.28 |

92.31

|

Petitioners

|

1,013,871 |

22.17

|

10.99

|

11.53 |

1.02 |

76.81

|

Respondents

|

63,374

|

34.89

|

10.53

|

9.93

|

1.20 |

78.80

|

Advocates

|

210,389

|

29.01

|

9.35

|

13.41 |

1.67 |

75.88

|

Note: (i) Since the SECC was conducted by interviewing the designated

head of the household, and only 9.7% of women in Bihar were coded as

household heads, we do not present the estimates of gender from this

survey; (ii) Estimates for Advocates, Petitioners, Respondents and

Judges are calculated using our data from the Patna High Court,

2009–2019.

|

Judges: We constructed a database of all 83 judges

who have served at the Patna High Court, including estimates of their

years of service at the court, but also their age, recruitment source,

date of appointment as an additional judge, date of appointment as a

permanent judge, and retirement date from handbooks from 2014, 2017 and

2020.

Table 1 summarizes occupational choices across caste, religious, and

gender identities in Bihar. We note that no professional group perfectly

represents the state's population. Judges however, are particularly

distinctive: mostly “Hindu Other” with no ST judges, few minorities, 6%

women, and <10% Muslim. Women are underrepresented across all

professions (10–26%). Government employees most closely reflect Bihar's

population, likely due to affirmative action programs that have been

described in the previous section.

For the sake of a historical comparison, we also draw on a newly

compiled dataset of Indian surnames from Ancestry.com and

familysearch.org, two leading websites that have attempted to gather

detailed ancestral records for individuals who once served in the

British Indian Army or the British Indian government that was present in

India until 1947. These sources offer insights into historical name

prevalence in Bihar, an early British-administered region. We use this

data solely for analyzing the frequency of specific surnames.

Names at the Patna High

Court

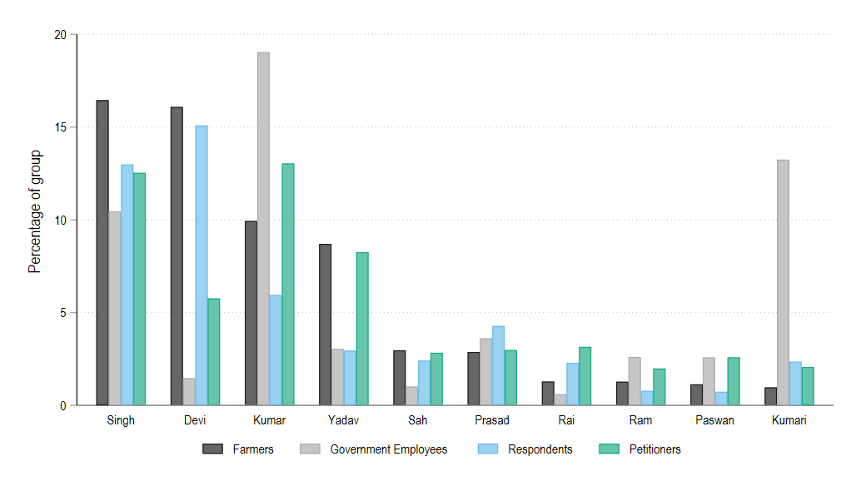

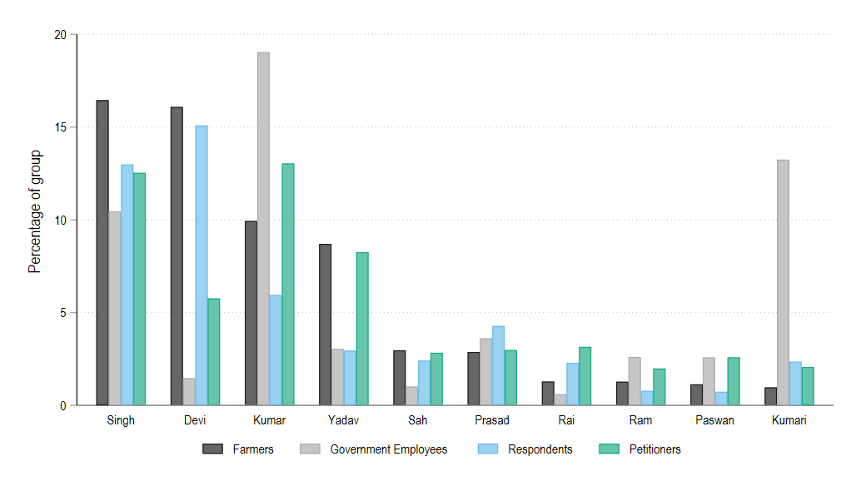

Figure 3. Proportion of sample, by top-10

surnames.

North Indian naming conventions typically assign given and surnames

at birth, with the latter indicating region, caste, and religion. As

noted earlier in this paper, name changes that are made later in life

typically focus on surnames (see footnote 2). We examine the frequency

of surnames, and again use the terms ”names” and “surnames”

interchangeably as we examine these distributions.

Figure 3 compares the most commonly used names at the Patna High

Court and other official settings. We note that the top 10 names (not

including the judges data) are remarkably similar everywhere. Singh,

Kumar, Kumari, Prasad, Yadav, Paswan, Ram, Jha Sinha, and Mishra occur

the most frequently. These specific names alone account

for 58% of senior government employees, 59% of farmers, 40% of

petitioners and 29% of respondents at the Patna High Court.

Figure 3 reveals a variation in dominant names across different

contexts. Singh represents 10% of senior government employees, 14% of

farmers, and 12% of High Court petitioners. Kumar comprises 19% of

senior government employees but only 7% of farmers. Yadav, less common

overall, accounts for 3% of government employees, 7% of farmers, 4% of

High Court petitioners, and 0.2% of respondents. Historically, Yadav

represented 11% (1931 Census), 14% (2011 Census), and 7% (SECC) of

Bihar's population. No judges have this surname.

A closer examination of names reveals the complex interplay between

caste identity and social status. In Bihar, ‘Kumar’ and ‘Devi’ are

widely regarded as caste-neutral names that are generally adopted to

conceal SC or OBC affiliation. ‘Singh’ is typically associated with

several FCs as well as OBCs, but is rarely used by any SCs. These names

are caste-neutral to the extent that they do not definitively indicate a

specific caste group or position in the caste hierarchy. Yadav on the

other hand, strongly indicates OBC status.

The high concentration and strong localization of names in Bihar

presents a striking contrast with other historical settings. For

instance, in 1541 London, only 7.85% of the population shared the top 10

most common surnames (Greif and Tabellini 2017). In China however, we

see a much greater concentration of names and the persistence of

clan-based networks at this time (Greif and Tabellini 2017; Fan et al.

2024). Though a high concentration of names has often been interpreted

as evidence of limited in-migration and upward mobility, the high

concentration of caste-neutral names may suggest a more complex social

dynamic at play in Bihar (Clark and Cummins 2015; Clark 2014).

Analysis of Names for Markers of

Social Identity

Algorithmic Inference of

Names

To identify religion of all litigants, advocates, and judges in our

sample, we first extract all surnames from Patna High Court cases

related to the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986

and Hindu Marriage Act, 1955. Assuming that only those from these

religious backgrounds file such cases, this is a comprehensive dataset

of Hindu and Muslim names that are widely used in Bihar.

The names database functions as training data for a machine learning

algorithm that predicts whether any name is Hindu, Muslim, or Other. When the algorithm is given a name

to analyze, it examines 1–4-character groups, noting distinctive

features associated with names in the religious group. For example, for

Muslim names (relative to Hindu names), it notes features such as the

higher incidence of the alphabet’s ‘z’ and 'q', or the higher frequency

of the co-occurrence of “mm” or “ee”. After this logistic regression

models are used to make out-of-sample predictions of the caste and

religious affiliation.

Next, we refine this algorithm to predict caste affiliations. For

this, we use SECC data. Since each household head in the SECC was asked

to report their full name and their caste affiliation, we have a

distribution of caste groups associated with names. We split the SECC

randomly into training data (90%) and testing data (10%). We use the

training data to make a list of predicted caste affiliations for the

top-100 names and then use out-of-sample predictions on the testing data

to determine the accuracy. We flag a name as “caste-neutral” if at least

15% of respondents report a different status than the rest of the group.

Using this threshold, of the 22,390,585 households in the SECC data,

approximately 23% reported caste-neutral names.

The accuracy of our algorithm in the in-sample SECC data was 92% and the

accuracy of our prediction on the testing group (also in the SECC data)

was 87%.

The final caste prediction is thus the outcome of a random variable

whose distribution over the categories is given by the distribution of

the surname over the social categories in the training data. The key

assumption made here is that the statistical composition of the

population is the same as that of the set of people appearing in the

courts data.

We note a stochastic component to this classifier. The same name

could be predicted to be of a different category when the classifier is

reapplied, however the probability of a specific category is dictated by

the normalized name counts. The name Trivedi for example, has the

normalized weights on [Other, SC, ST] given by [1,0,0], so it is always

predicted to be of the ‘Other’ category. In contrast, the name Kumar has

weights given by [0.88, 0.12, 0.01], so although there is a very high

chance that the name is predicted as ’Other’, there is also more than

12% chance that it is predicted as ’SC’.

To further validate the predictions of religion and caste that emerge

from this method, we also conduct a small and informal survey of elderly

residents of Patna. We interviewed a dozen elderly women in the city of

Patna who had spent their entire lives in the state and had extensive

knowledge of social structures in the state. The goal was to check what

associations, if any, were made between specific surnames and markers of

caste and religion. We presented survey respondents with a list of

names, followed by a series of questions about the caste, or religious

background associated with the name. We found that Muslim names were

universally acknowledged as such, alongside upper-caste names like

Bhumihar Brahmins (who have names such as Ojha, Pande or Upadhyaya).

Names associated with dominant castes in Bihar’s politics (such as

Yadav) are also immediately understood to be from the OBC category.

Nearly all respondents said that within the Hindu community, certain

names were completely caste-neutral and no clear inference could be made

about a person's caste from these names.

Caste-Neutral Names: Broad

Patterns of Use

We identify 16 caste-neutral names through algorithmic assignment and

qualitative research: Kumar, Kumari, Prasad, Singh, Sinha, Mandal,

Mishra, Baitha, Bharthi, Das, Dev, Devi, Safi, Ram, Rai, and the many

variants of the name Chaudhary (this includes Chowdhry, Chowdhury,

Choudhary, Chaudhry, Chowdhry, Chodhry, etc.). As noted earlier, some of

these names, such as Prasad, Mandal and Ram, are widely regarded as

low-caste names that have been increasingly adopted to conceal severe

historical marginalization in Bihar. In our analysis we will thus group

SC and neutral names as ”low-status” and also examine them

separately.

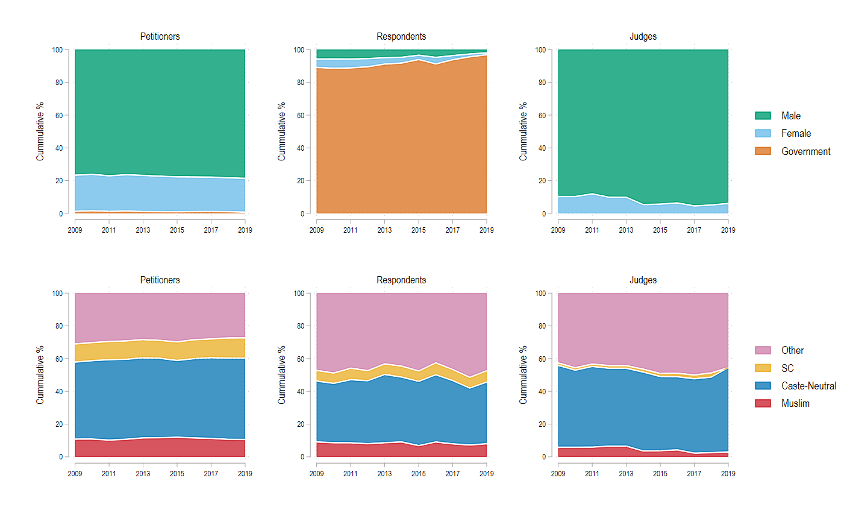

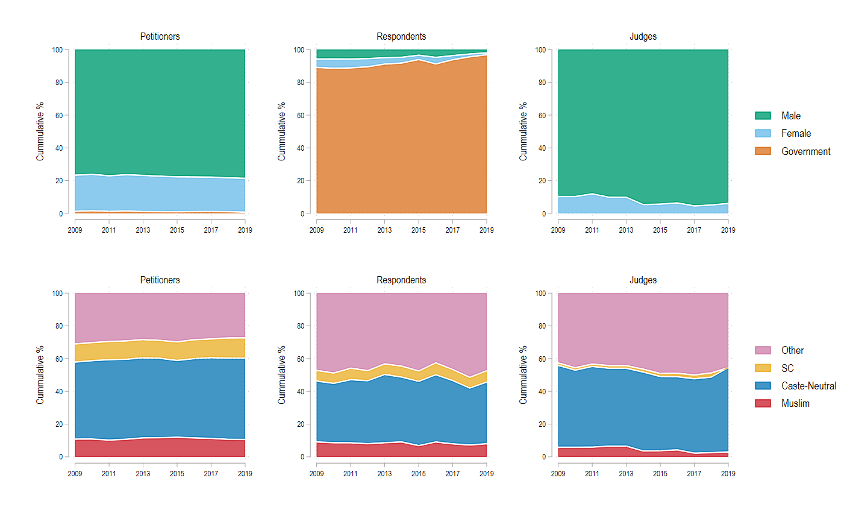

Table 2 shows 49% of petitioners and 56% of respondents use

caste-neutral names, while 12% and 10% use SC-sounding names

respectively. Similar trends exist for advocates. Figure 4 illustrates

these trends over time, with caste-neutral names consistently remaining

quite high (approximately 50%). Judges show slight fluctuations, ranging

from 50% to 43% between 2009 and 2019. Appendix Table A1 presents

similar statistics for the merged data sample.)

| Case Data |

N |

Mean |

SD |

Min |

Max |

| Civil Case |

1,071,068 |

0.34 |

0.47 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

| Petitioner is Muslim |

1,032,838 |

0.12 |

0.32 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

| Respondent is Muslim |

64,449 |

0.11 |

0.31 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

| Petitioner’s Advocate is Muslim |

1,068,991 |

0.05 |

0.22 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

| Respondent’s Advocate is Muslim |

959,450 |

0.12 |

0.32 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

| Petitioner is SC |

1,001,830 |

0.12 |

0.32 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

| Respondent is SC |

58,849 |

0.10 |

0.30 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

| Petitioner’s Advocate is SC |

1,040,380 |

0.06 |

0.24 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

| Respondent’s Advocate is SC |

841,301 |

0.07 |

0.25 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

| Petitoner has Caste-neutral Name |

1,001,846 |

0.50 |

0.50 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

| Responndent has Caste-Neutral Name |

58,851 |

0.57 |

0.50 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

| Petitoners’s Advocate has Caste-Neutral Name |

1,040,380 |

0.63 |

0.48 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

| Respondent’s Advocate has Caste-Neutral Name |

841,304 |

0.59 |

0.49 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

| Judge Data |

|

|

|

|

|

| Judge has Caste-Neutral Name |

83 |

0.53 |

0.50 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

| Judge is SC |

83 |

0.02 |

0.14 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

| Judge is Muslim |

83 |

0.06 |

0.24 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

| Judge is a Woman |

83 |

0.10 |

0.30 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

| Year of birth |

79 |

1956.13 |

5.56 |

1947.0 |

1969.0 |

| Year when became permanent |

30 |

2009.00 |

7.38 |

1991.0 |

2019.0 |

| Was Chief Justice |

83 |

0.13 |

0.34 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

| Promoted to Supreme Court? |

83 |

0.08 |

0.28 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

Figure

4. Trends of Petitioners, Respondents and Judges by Gender and

Caste. The lower panels for petitioners and respondents are at the case

level and include only cases where the petitioner and respondent are

identified as individuals, respectively. The judge panel includes each

judge with at least one case in the Patna HC in a given year exactly

once.

Figure

4. Trends of Petitioners, Respondents and Judges by Gender and

Caste. The lower panels for petitioners and respondents are at the case

level and include only cases where the petitioner and respondent are

identified as individuals, respectively. The judge panel includes each

judge with at least one case in the Patna HC in a given year exactly

once.

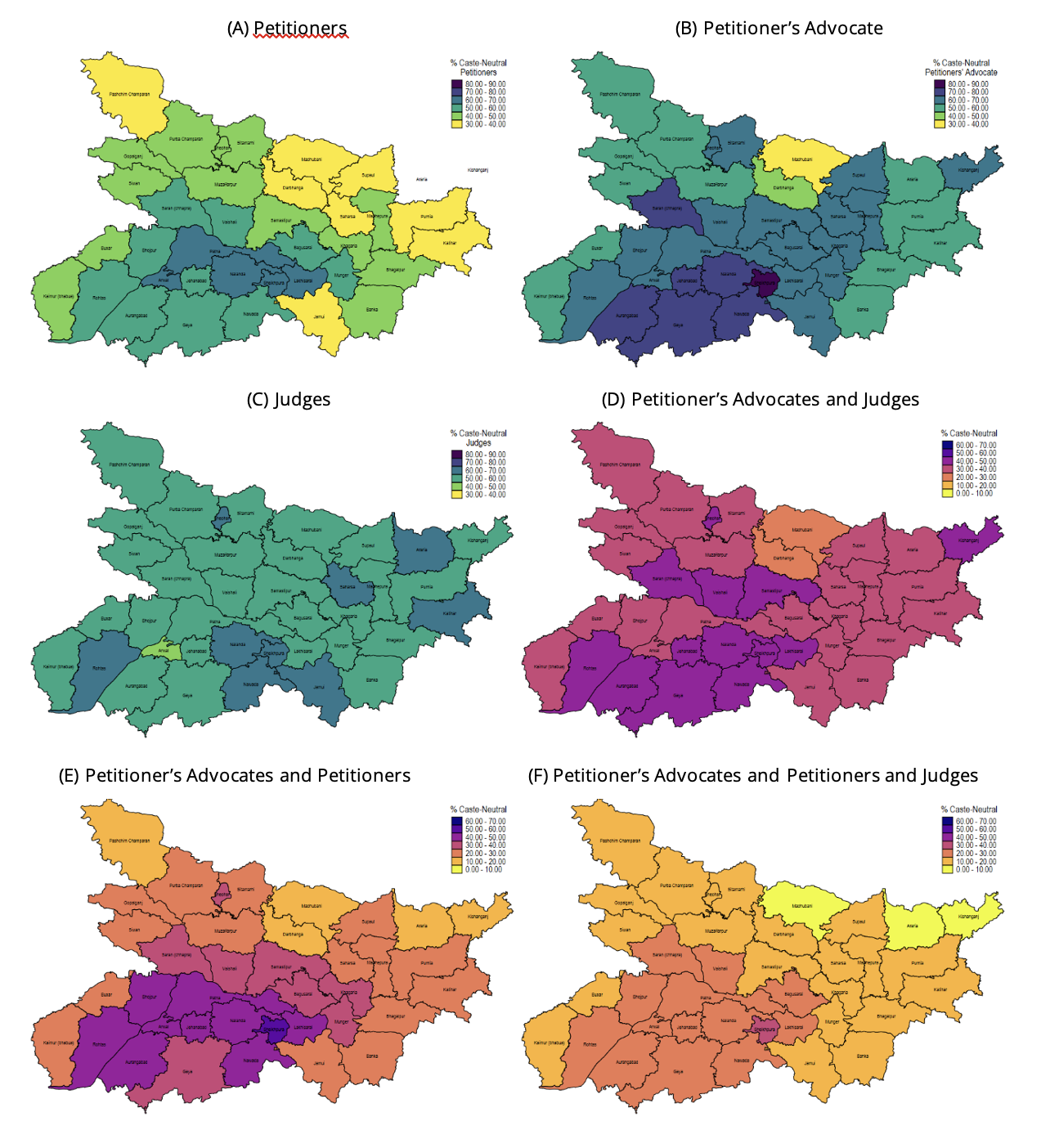

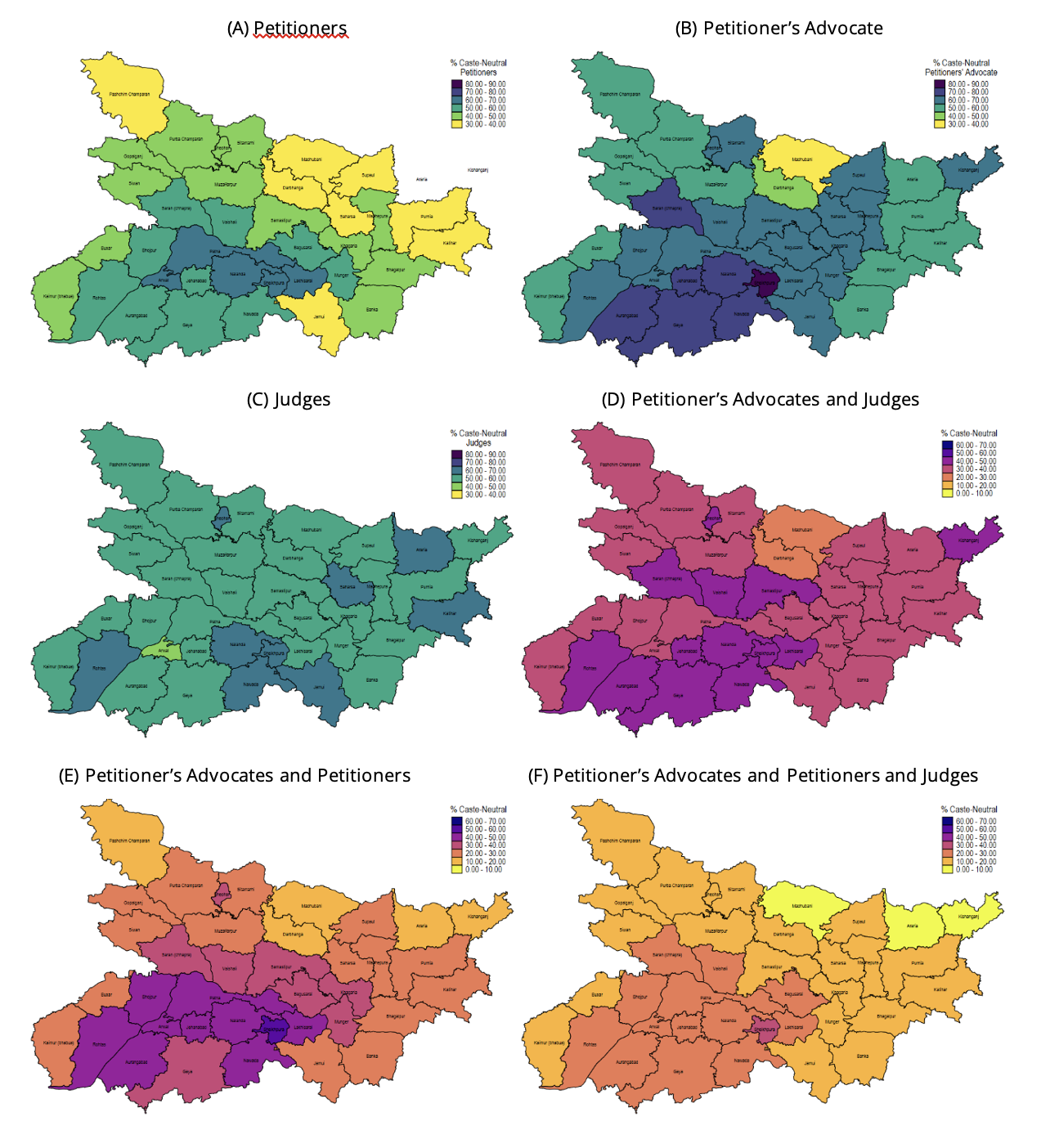

In Figure 5 we explore the spatial distribution of the use of

caste-neutral names by petitioners (panel A), petitioner advocates

(panel B) and judges (panel C). Note that there is considerable

variation by district, among all three sets of stakeholders. The

prevalence appears to be lowest in the northern and eastern regions of

the state. These are mostly rural areas where governance is weaker,

lawlessness is greater and strife along the lines of caste and religion

have been common in Bihar’s recent history (Chakrabarti 2013; Kumar

2018).

Conversely, the practice of using caste-neutral names seems to be

most favored in Patna, the largest city in Bihar, which also has the

highest proportion of civil cases (Figure 5). In Panels (D)–(F) of

Figure 5 we explore the overlaps of these three categories.

Specifically, we note that the likelihood of seeing caste-neutral

petitioners, advocates and judges, in any combination, matched on a

single case is the highest in the southern and relatively urbanized

districts around Patna. These include Nalanda, Gaya, Sheikhpura, Newada,

Aurangabad, and Bhojpur.

The prevalence of caste-neutral names in urban areas likely reflects

a complex interplay of factors. While it may partially stem from

increased social mobility and education levels, as well as efforts to

mitigate overt caste-based discrimination in professional settings

(Srinivas 1957), it would be an oversimplification to view this trend as

a straightforward erosion of caste identity. Rather, previous

scholarship emphasizes the adaptability of the caste system – it often

reconfigures itself within urban contexts and modern labor markets,

taking on new forms and expressions (Bayly 2001; Deshpande 2011; Jodhka

2017; Munshi 2019).

This rise of caste-neutral names is however, a recent phenomenon. We

illustrate this by exploring incidence of caste-neutral names in the

records of the British Indian army in the year 1912 (as seen on the

website Ancestry.com). Of the more than 100,000 names, we find almost no

records of any individuals with caste-neutral names such as Sinha and

Kumar (N=65). Though we find many instances of the name Singh (N=8,562),

the percentage of the population with this name is still lower than any

estimate in our contemporary data. While this could be the result of

colonial policies that sought to achieve communal balance in the

administration through caste- and religion-based recruitment (Bayly

2001; Dirks 1989), the near-complete absence of many names that are

among the most common ones today is quite striking. This suggests that

the prevalence of caste-neutral names in Bihar may indeed be a

relatively recent development, potentially reflecting changing social

dynamics and identity formation in the post-colonial era.

Matching on the Basis of Social

Identity

To comprehend the potential for social identity-based matching or

selection among petitioners, respondents, their advocates, and judges,

it is crucial to examine the procedural dynamics within the court

system. The judicial process unfolds through several distinct stages.

Initially, a petitioner initiates legal action against a respondent,

with both parties securing representation by advocates. The petitioner's

lawyer then files the case, after which the Chief Justice assigns a

judge to preside over the matter. As the case progresses, additional

arguing lawyers may be engaged based on their courtroom expertise and

track record with specific judges (Galanter and Robinson 2017). This

sequence of events provides multiple junctures where social identity

could potentially influence decisions and interactions, from the initial

selection of legal representation to the assignment of judges and the

engagement of additional counsel.

One of the most important decisions a petitioner makes is their

choice of advocate or lawyer. The judicial system allows petitioners and

respondents to choose their lawyers. Judges however, are assigned

through the ”roster system” by the Chief Justice, aiming for objective

case allocation. Roster changes typically result in judge reassignment,

except for cases in final argument stages. Courts actively prevent

judges from handling cases involving familial or social connections,

with conflict of interest lists updated regularly. Previous work has

demonstrated that judge assignment at the high courts is random

(Chandra, Kalantry, and Hubbard 2023; Ash et al. 2022).

Figure 5. Spatial distribution of the use of

caste-neutral names for cases filed at the Patna HC from 2008 to 2019.

Districts with the fewest observations are dropped and marked in red.

Note also the different scale between Panels A to C (10–80%) and Panels

D to F (0–50%).

With this background, we first examine matching between judges and

petitioners. Given the stringent rules of the roster system, our first

hypothesis, which we will call Hypothesis (A), is that the identity of

the petitioner should not be associated with the identities of the

judges assigned to a case. Specifically, we consider the following

model:

\({LitigantIdentity}_{cydt} = \beta_{0} +

\beta_{1}{MatchedJudge}_{cydt} + \Theta X_{c} + \alpha_{y} + \nu_{d} +

\phi_{t} + \epsilon_{cydt}\) (1)

Here \({LitigantIdentity}_{cydt}\)

denotes the social status of either petitioners or respondents of case

\(c\) of type \(t\) in year \(y\) and district \(d\). \({MatchedJudge}_{cydt}\) denotes the

identity of the judge selected by the litigant. \(\phi_{t}\), \(\alpha_{y}\) and \(\nu_{d}\) correspond to case-type, year,

and district fixed-effects respectively.

Next, we turn to the case of matching between advocates and judges.

Court rules allow petitioners to switch advocates during a case. If a

judge has a strong relationship with a lawyer, a petitioner can recruit

that lawyer. Assuming similar group identities facilitate communication,

we may see judge-lawyer matching (excluding the judge’s official list of

excluded people). However, our data only shows filing advocates. As

these are chosen before judge assignment, random assignment leads to

Hypothesis (B): Identity of petitioner advocates filing the case in the

high court should not be associated with the identities of the judges

assigned to the case.

Specifically, we use the following model:

\({AdvocateIdentity}_{cydt} = \beta_{0} +

\beta_{1}{MatchedJudge}_{cydt} + \Theta X_{c} + \alpha_{y} + \nu_{d} +

\phi_{t} + \epsilon_{cydt}\) (2)

Here \({AdvocateIdentity}_{cydt}\)

denotes the social status of either petitioner’s or respondent’s

advocates of case \(c\) of type \(t\) in year \(y\) and district \(d\). \({MatchedJudge}_{cydt}\) denotes the

identity of the judge selected by the litigant. \(\phi_{t}\), \(\alpha_{y}\), and \(\nu_{d}\) are as in Equation (1).

Finally, we examine the matching between litigants and the lawyers

who represent them. Here, official rules provide a great deal of choice.

In cases like bail applications, petitioners can file in lower and high

courts, and transfer dismissed cases. Given court complexity, backlogs,

and hierarchy, using an advocate from one’s community is advantageous.

Lawyers in close contact ensure timely file transfers. This leads us to

Hypothesis (C): Identity of the advocates representing petitioners

should show strong association with the identities of the petitioners.

To test this, we use the following model:

\({LitigantIdentity}_{cydt} = \beta_{0} +

\beta_{1}{AdvocateIdentity}_{cydt} + \Theta X_{c} + \alpha_{y} + \nu_{d}

+ \phi_{t} + \epsilon_{cydt}\) (3)

Here \({LitigantIdentity}_{cydt}\)

denotes the social status of either petitioners or respondents of case

\(c\) of type \(t\) in year \(y\) and district \(d\). \({AdvocateIdentity}_{cydt}\) denotes the

social status of their advocates respectively. \(\phi_{t}\), \(\alpha_{y}\) and \(\nu_{d}\) are defined as in Equation

(1).

Our analysis unfolds in two stages. First, we categorize both SC and

caste-neutral names as “low-status”, examining the full sample of Hindu

litigants. We then compare caste-neutral names directly to SC names

within a restricted sample of petitioners or respondents using only

these name types. Throughout, we focus solely on first orders of each

case. To assess litigant-judge matching, we employ OLS regression with

controls for judge characteristics, clustering standard errors at the

district-year level and incorporating year, district, and case type

fixed-effects. This analysis excludes Muslim litigants, concentrating

exclusively on Hindu social identities. We explore religious matching

separately in other research.

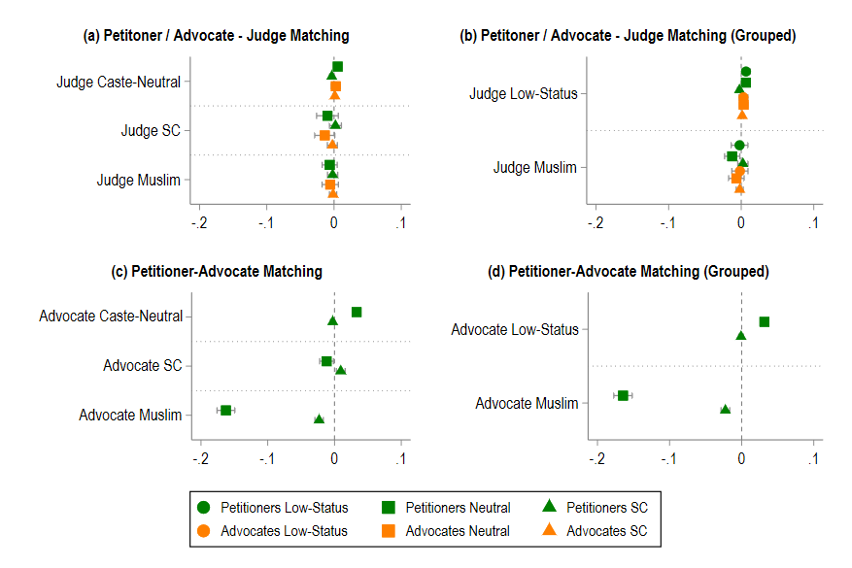

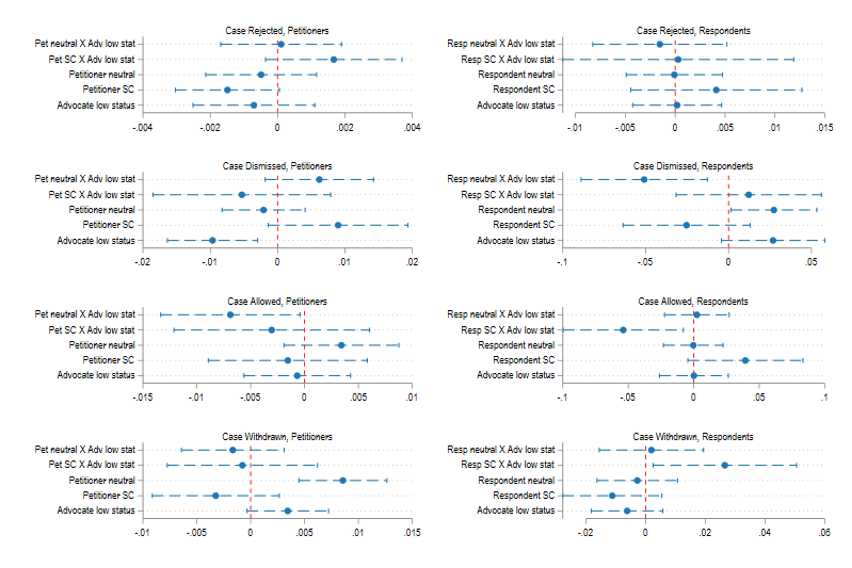

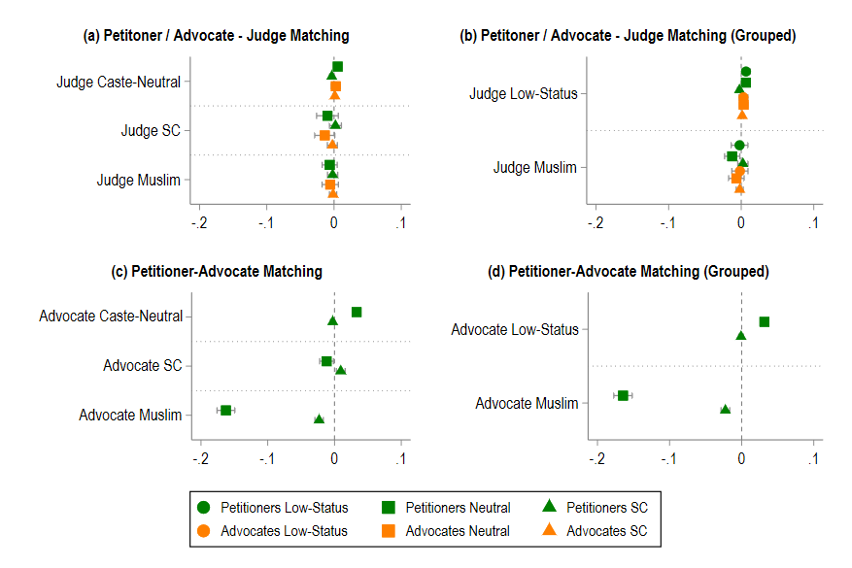

Results for all three hypotheses are presented in Figure 6. These

visuals present just the relevant coefficients from the regressions. The

green markers in the top-left and top-right panels of Figure 6 test for

matching between petitioners and judges based on their identities

(Hypothesis A). We find a significant coefficient for SC petitioners

matching with caste-neutral judges (b=-0.003, se=0.002). When grouping

together caste-neutral and SC together into the single “low-status”

group for petitioners or judges, we additionally find significant

coefficients for caste-neutral petitioners matching with low-status

judges (b=0.007, se=0.002) and Muslim judges (b=-0.012, se=0.005), and

low-status petitioners matching with low-status judges (b=0.007,

se=0.003). Though the confidence intervals for these regressions do not

include 0 we believe this effect size is just too small to be of

practical significance. Petitioners and judges do not appear to match on

the basis of this broader form of identity.

Figure 6.

Tests of Matching (Hypotheses A, B and C) for Caste-neutral and SC

petitioners/advocates. Hypothesis (A): Petitioners matching with judges;

Hypothesis B: Petitioners advocates matching with judges, and Hypothesis

C: petitioners matching with advocates; Sample includes only judges from

the first observable order in the regression. Panel (a) and (b) present

results from regressing petitioner's and their advocate's identities on

the identity of the first judge assigned to the case. Panel (c) and (d)

present results from regressing petitioner's identities on their

advocate's identities. “Low-Status” groups caste-neutral and SC names

together. All regressions control for the age of the judge, if the judge

pursued their career in the supreme court, the number of years the judge

has a permanent position in the high court, the district, the filing

year, and for the case type. Regressions are estimated separately across

petitioner's (all panel) and advocate's (panel a and b) identities.

Standard errors are clustered at district and year level. Confidence

intervals correspond to 5% statistical significance.

Figure 6.

Tests of Matching (Hypotheses A, B and C) for Caste-neutral and SC

petitioners/advocates. Hypothesis (A): Petitioners matching with judges;

Hypothesis B: Petitioners advocates matching with judges, and Hypothesis

C: petitioners matching with advocates; Sample includes only judges from

the first observable order in the regression. Panel (a) and (b) present

results from regressing petitioner's and their advocate's identities on

the identity of the first judge assigned to the case. Panel (c) and (d)

present results from regressing petitioner's identities on their

advocate's identities. “Low-Status” groups caste-neutral and SC names

together. All regressions control for the age of the judge, if the judge

pursued their career in the supreme court, the number of years the judge

has a permanent position in the high court, the district, the filing

year, and for the case type. Regressions are estimated separately across

petitioner's (all panel) and advocate's (panel a and b) identities.

Standard errors are clustered at district and year level. Confidence

intervals correspond to 5% statistical significance.

When testing Hypothesis B, we repeat this analysis for advocates and

judges. The orange markers in the top-left and top-right panels of

Figure 6 present the coefficients and 95% confidence-intervals of these

regressions. Here we do not find any coefficient which is significant at

the 5% level. The key finding here is that caste-neutral or SC advocates

are not more likely to match with judges from their own social group in

our simple specification.

This result is broadly consistent with recent literature that has

argued that judge assignment at the Indian courts appears to be

as-good-as-random. Chandra, Kalantry, and Hubbard (2023) use more than a

decade of data on cases at the Supreme Court to demonstrate that the

Supreme Court randomly assigns cases to small benches. While these

authors did not study the High Courts, the unified structure of the

Indian justice system requires the protocols that are followed at High

Courts to be aligned with the apex court. Ash et al. (2022) use a

database of 5.5 million criminal cases in the entire Indian justice

system to test for religious and gender bias in case assignment as well

as case outcomes and report “tight zero effects of in-group bias”.

This may result from strong judicial impartiality norms or the

robustness of the case assignment roster system (Gadbois 2011; 2018).

However, we caution that our analysis only considers filing lawyers;

petitioners may later appoint lawyers known for rapport with specific

judges after case assignment.

Figure 7. Decision Tree for Cases

Results to test hypothesis (C) are presented in the bottom panels of

Figure 6. In the bottom-right panel we observe that caste-neutral

petitioners are 3% more likely to choose a low-status advocate and 16%

less likely to choose a Muslim advocate compared with higher caste. SC

petitioners however, are not more likely to choose a low-status advocate

over a high-status advocate and are only 2% less likely to choose a

Muslim advocate.

The left-bottom panel of Figure 6 uncovers these results a bit

further. Especially, it shows that the 3% higher likelihood of

caste-neutral petitioners choosing lower status advocates really stems

from these petitioners choosing caste-neutral advocates and not SC

advocates. We interpret this as caste-neutral petitioners having a

distinct identity in the judicial system, even compared to SC

petitioners.

In summary, we see that petitioners who use caste-neutral names

appear to be more likely to show in-group matching than their

counterparts with SC names. We infer from this that even though both

neutral names and SC names may be regarded as low-status names in Bihar,

they contain different markers of social identity at the courts.

Caste-neutral petitioners are the most likely to match with advocates

that also have caste-neutral names.

Outcomes of Justice: Regression

Analysis

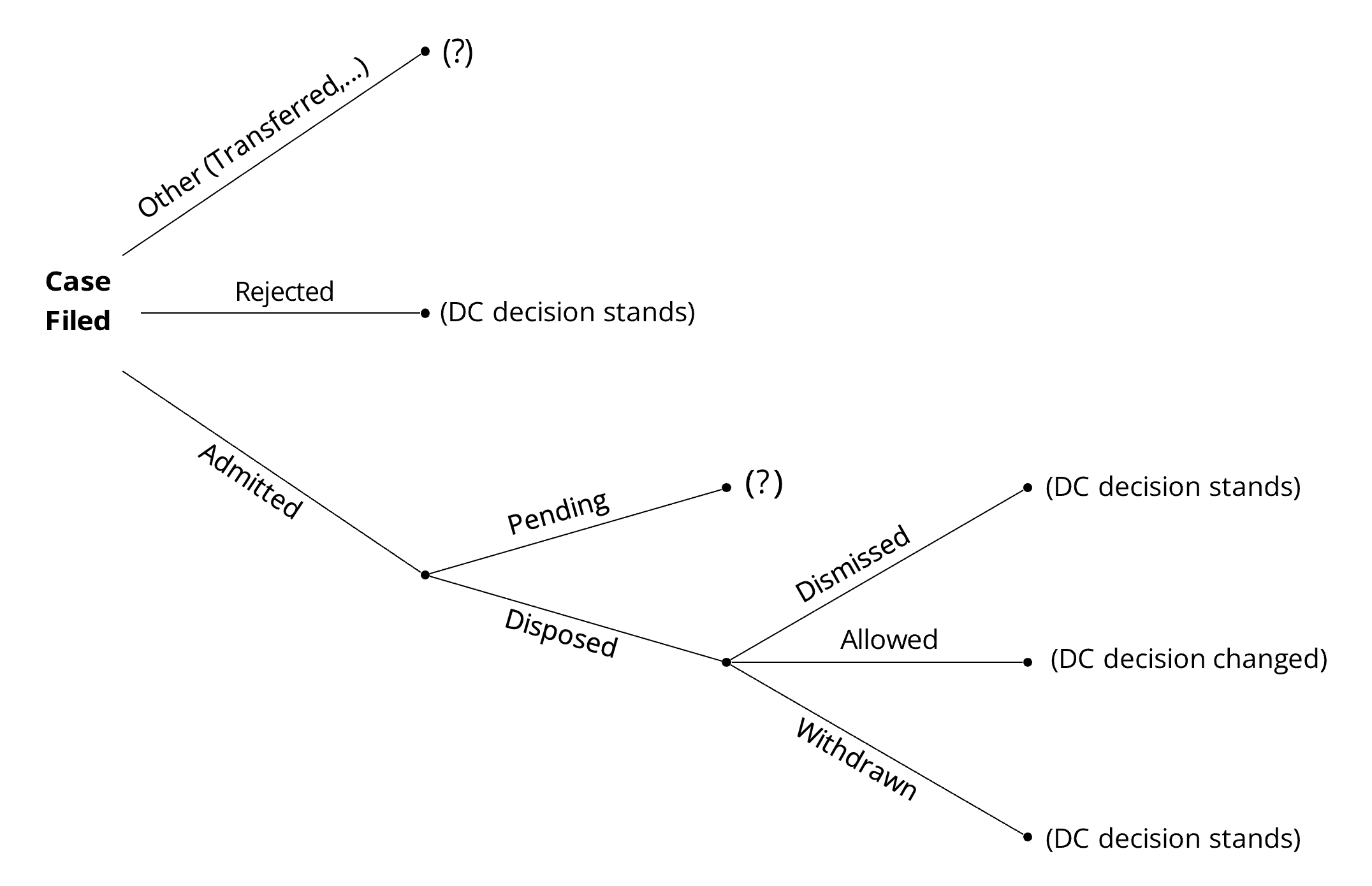

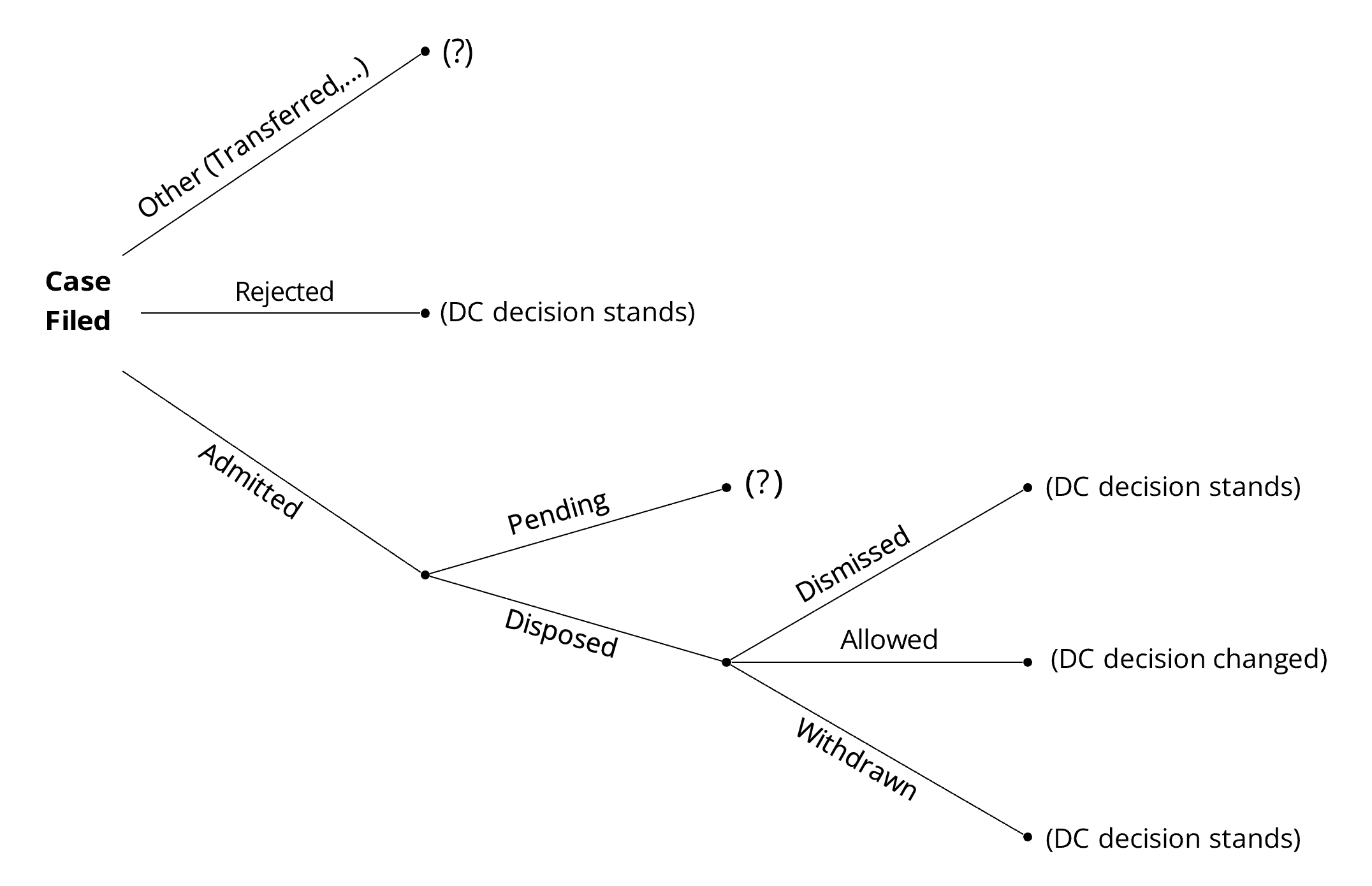

Next we examine the outcomes of the justice system. Here we rely on

official court terminology. Cases are initially

“Admitted” or “Rejected”. Admitted cases proceed to the High Court and

are “Disposed” upon decision. Disposals can be “Allowed”, “Dismissed”,

or “Withdrawn”. Figure 7 illustrates these stages

and potential outcomes.

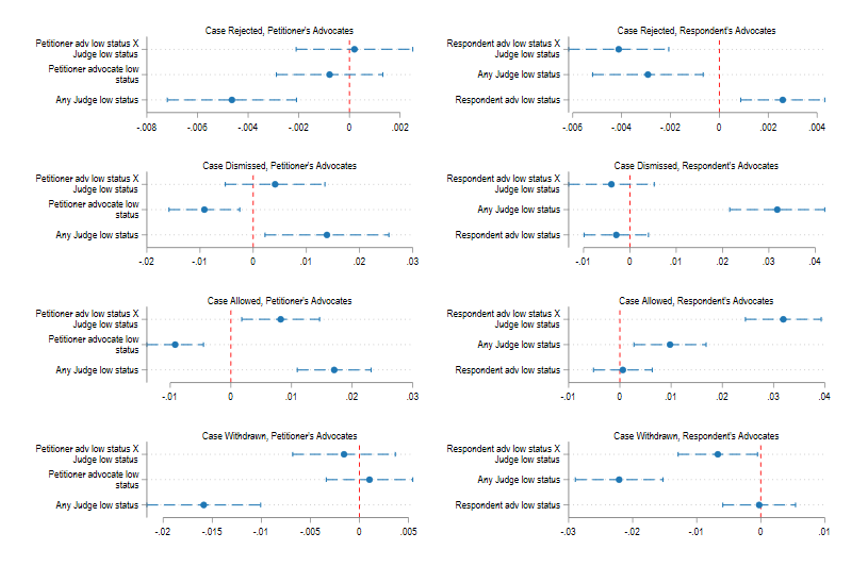

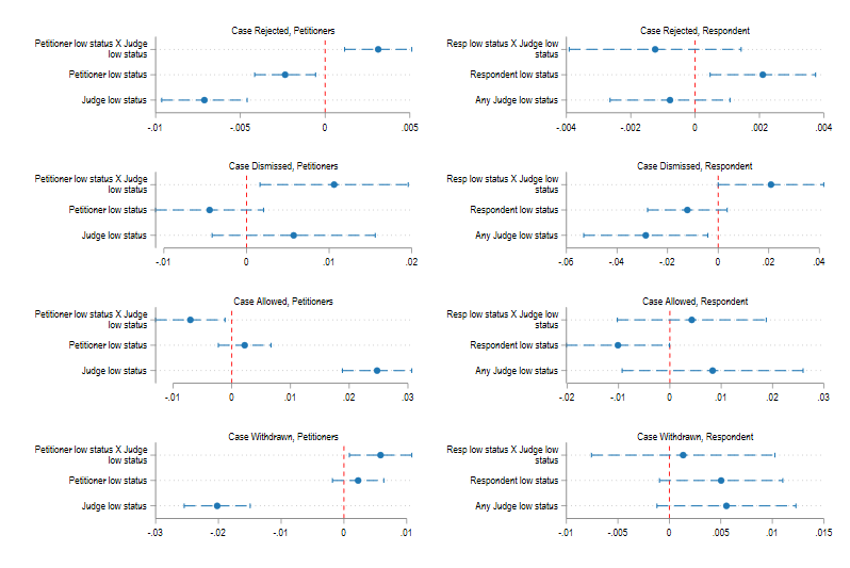

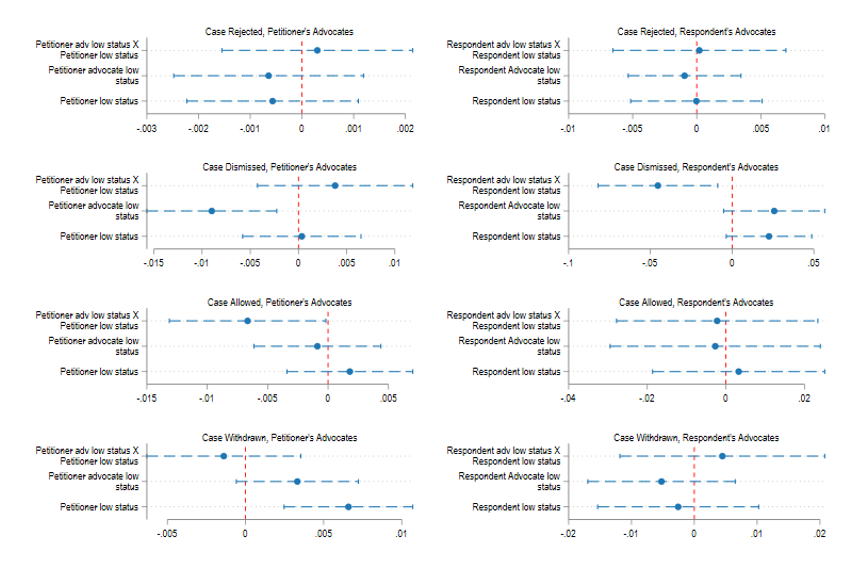

Figure 8. Case outcomes: Matching between

low-status litigants (petitioners and respondents) and judges on the

basis of identity. Low-status includes both SC and caste-neutral

litigants. Regressions are based on the first observed order for a

specific court case. Definition of judge identity is based on any judge

on the bench with that identity. All regressions control for district,

year and the type of case fixed-effects. Standard errors are clustered

at district and year level. Confidence intervals correspond to 5%

statistical significance.

To analyze the impact of social identity on case outcomes, we

consider the following model:

\[y_{cydt} = \beta_{0} + \beta_{1}\lbrack

PetitionerIdentity\rbrack_{i} + \beta_{2}\lbrack

AdvocateIdentity\rbrack_{j} + \beta_{3}\lbrack Petitioner \times

Advocate_{(i,j)}\rbrack + \delta X_{c} + \alpha_{y} + \nu_{d} + \phi_{t}

+ \epsilon_{cydt}\]

Here \(y_{cydt}\) denotes the

outcome of case \(c\) of type \(t\) in year \(y\) and district \(d\). We focus here on the outcome of the

case (rejected, dismissed, withdrawn and resolved). In additional

results (included in the Appendix), we also examine the status of the

case (whether or not it has been decided) and the time taken to a

decision (in months).

The sub-scripts \(i\) and \(j\) denote the types of social identity on

the basis of names. We consider three types of groups: All low-status

litigants (which includes those with caste-neutral or SC names) and

caste-neutral and SC names separately. Once again, we include year,

district, and case type fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at

a district-year level. We restrict our sample only to first orders of

any case.

In line with our approach in the prior findings, we exclude Muslims

from the litigant sample, focusing exclusively on Hindus. Our analysis

begins by exploring in-group matching effects among petitioners and

respondents to their respective advocates, with SC and caste-neutral

names grouped together in a single category “low-status”. Subsequently,

we separate out the caste-neutral and SC names to examine how these

differ from each other.

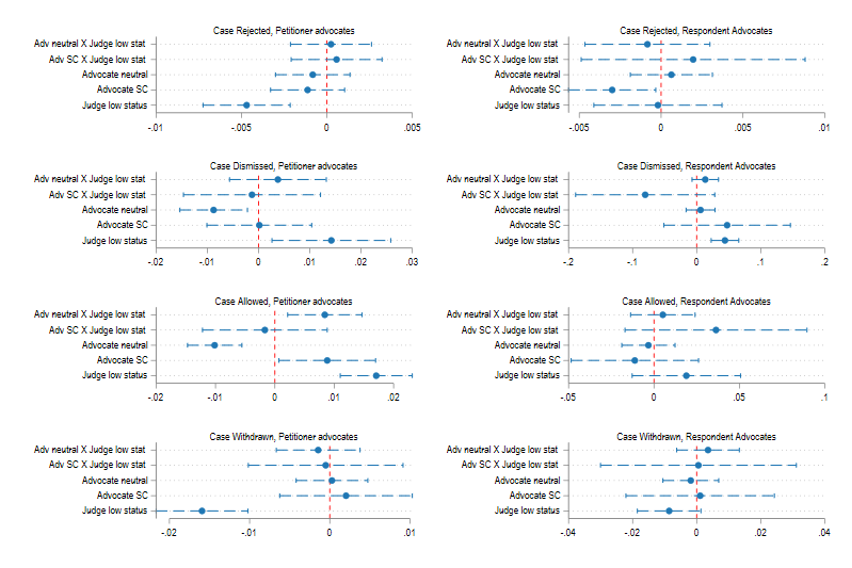

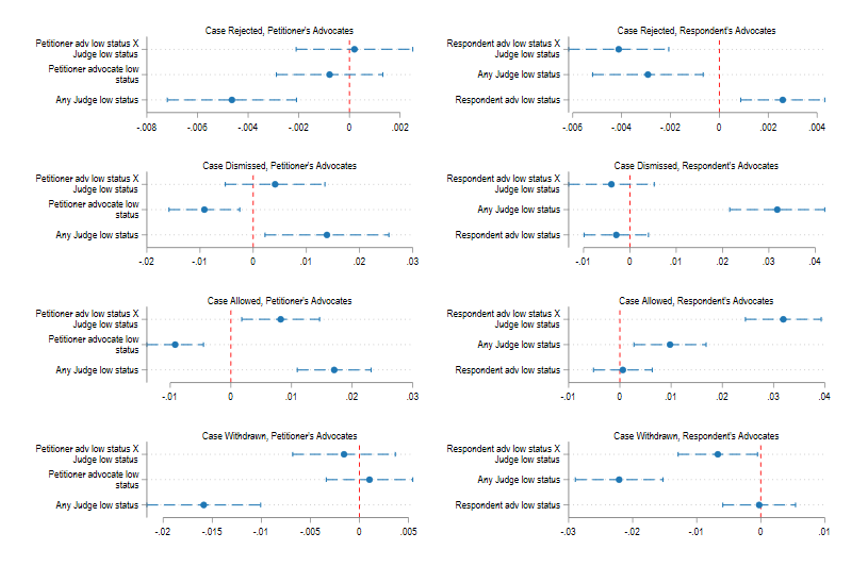

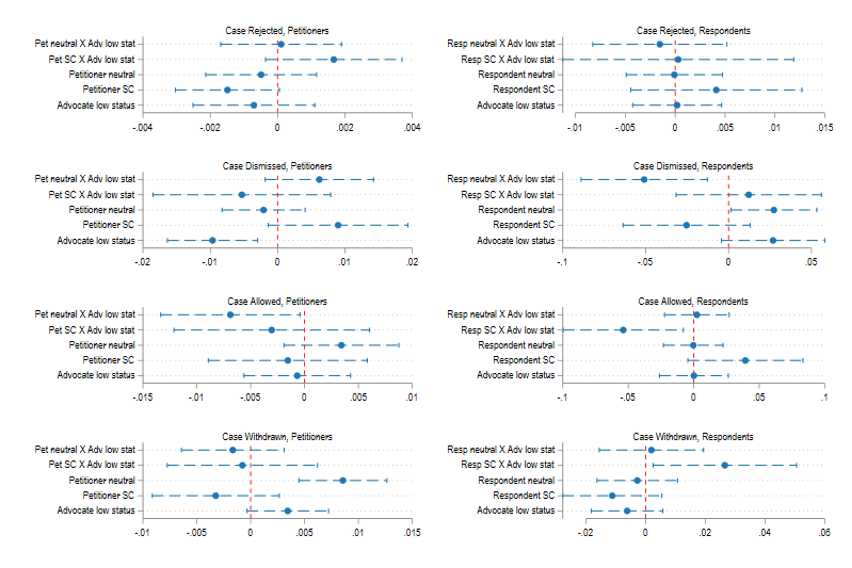

Figure 9. Case outcomes: Matching between low-status

advocates (petitioners and respondents) and judges on the basis of

identity. Low-status includes both SC and caste-neutral litigants.

Regressions are based on the first observed order for a specific court

case. Definition of judge identity is based on any judge on the bench

with that identity. All regressions control for district, year and the

type of case fixed-effects. Standard errors are clustered at district

and year level. Confidence intervals correspond to 5% statistical

significance.

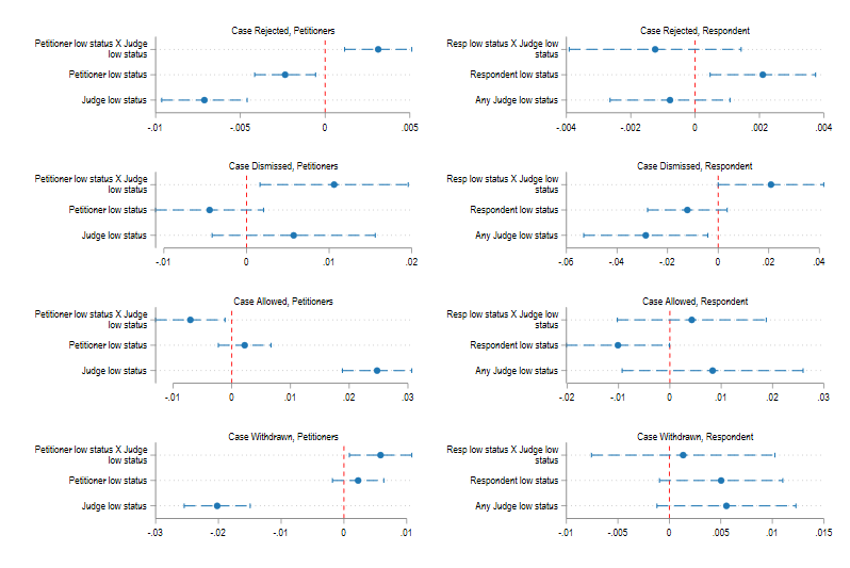

We begin by examining the impact of low-status petitioner-advocate

matches on case outcomes among Hindu litigants, with our findings

presented in Figure 8 (Petitioners and Respondents matching with

judges), Figure 9 (Advocates matching with judges) and Figure 12

(Petitioners and Respondents matching with Advocates). We present only

the most important coefficients in these figures. Full results, with

detailed tests of joint significance of the coefficients, are presented

in the Appendix (see Appendix Table A2 to Appendix Table A13).

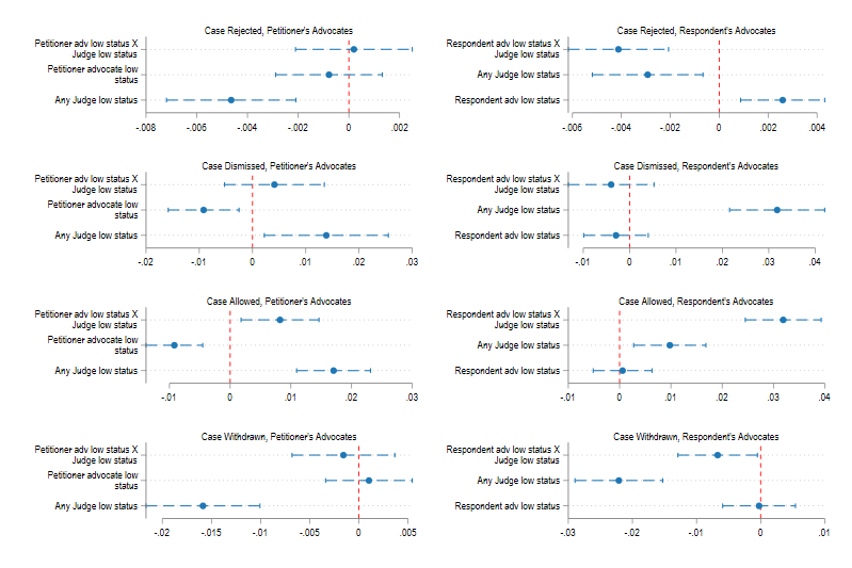

Figure 10.

Case outcomes: Matching between caste-neutral litigants (petitioners and

respondents) and judges on the basis of identity. Regressions are based

on the first observed order for a specific court case. Definition of

judge identity is based on any judge on the bench with that identity.

All regressions control for district, year and the type of case

fixed-effects. Standard errors are clustered at district and year level.

Confidence intervals correspond to 5% statistical significance.

Figure 10.

Case outcomes: Matching between caste-neutral litigants (petitioners and

respondents) and judges on the basis of identity. Regressions are based

on the first observed order for a specific court case. Definition of

judge identity is based on any judge on the bench with that identity.

All regressions control for district, year and the type of case

fixed-effects. Standard errors are clustered at district and year level.

Confidence intervals correspond to 5% statistical significance.

Matching between Litigants and

Judges

We first examine matching between litigants and judges. Figure 8

reveals subtle but statistically significant effects when petitioners

with low-status names are matched with judges of similar status. In

these cases, petitioners face a 0.3 percentage point (pp) higher

likelihood of rejection, a 1.1 pp increase in dismissal rates, a 0.7 pp

decrease in successful cases (categorized as “Allowed”), and a 0.6 pp

greater chance of withdrawal. While these effect sizes are small, they

all achieve statistical significance at either the 5% or 1% level

(Appendix Table A2). Notably, all of these outcomes are disadvantageous

to the petitioners, consistently reducing their chances of a favorable

result.

Regarding respondents, our analysis reveals only one statistically

significant outcome: a 2.1 pp increase in case dismissals (Appendix

Table A4). Given that respondents generally gain from having cases

dismissed, this is a notable result.

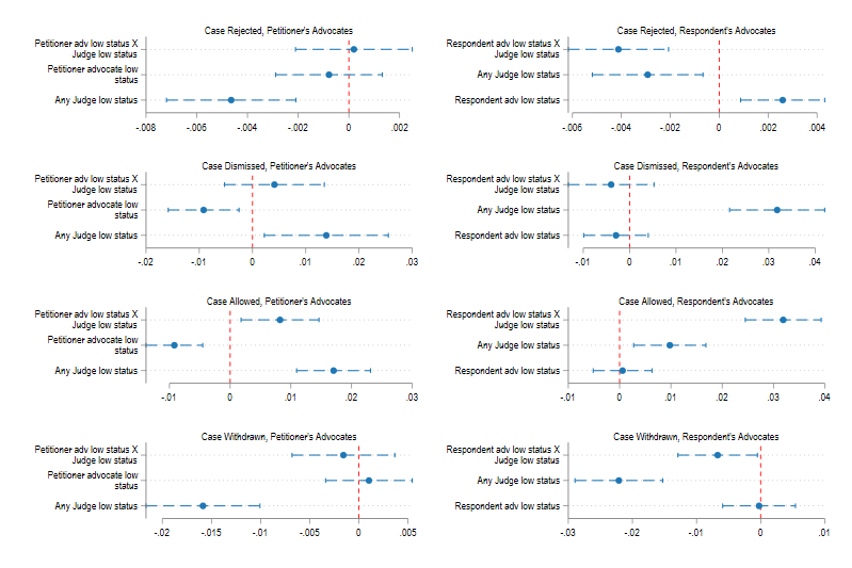

Figure 11.

Case outcomes: Matching between caste-neutral advocates (petitioners and

respondents) and judges on the basis of identity. Regressions are based

on the first observed order for a specific court case. Definition of

judge identity is based on any judge on the bench with that identity.

All regressions control for district, year and the type of case

fixed-effects. Standard errors are clustered at district and year level.

Confidence intervals correspond to 5% statistical significance.

Figure 11.

Case outcomes: Matching between caste-neutral advocates (petitioners and

respondents) and judges on the basis of identity. Regressions are based

on the first observed order for a specific court case. Definition of

judge identity is based on any judge on the bench with that identity.

All regressions control for district, year and the type of case

fixed-effects. Standard errors are clustered at district and year level.

Confidence intervals correspond to 5% statistical significance.

Next, we disaggregate the “low-status” variable for petitioners,

separately analyzing caste-neutral and Scheduled Caste (SC) petitioners

to evaluate their outcomes when paired with low-status judges. Figure 10

illustrates these effects, with comprehensive results presented in

Appendix Table A3. The coefficients for “Petitioner neutral x Judge

low-status” consistently show statistical significance and maintain

similar magnitudes as observed in Figure 8. Similar effects are seen for

case processing (Appendix Table A3). In contrast, the coefficients for

“Petitioner SC x Judge low-status” are smaller and lack statistical

significance. This pattern suggests that the previously observed

disadvantages are primarily concentrated among caste-neutral petitioners

rather than SC petitioners.

The random assignment of cases to judges underscores our findings’

significance: judge social identity influences case outcomes despite

unbiased case allocation. Moreover, caste-neutral petitioners appear

consistently disadvantaged when facing low-status judges.

Matching between Advocates and

Judges

Next we examine matching between advocates and judges. Figure 9 and

Appendix Table A6 reveal subtle but statistically significant effects

when petitioner's advocates with low-status names are matched with

judges of similar status. Here we see only one statistically significant

effect: advocates with low-status names who match with similarly

low-status judges are 0.8 pp more likely to have a successful case and

this effect is statistically significant at the 5% level (b=0.008,

se=0.003).

Examining respondents reveals a different pattern of disadvantages

(Figure 9 and Appendix Table A8). Cases involving these respondents show

a 0.4 pp decrease in rejection likelihood, a 3.2 pp increase in

allowance probability, and a 0.7 pp decrease in withdrawal rates. Each

of these outcomes is significant at least at the 5% level and represents

a disadvantage for the respondents involved.

As before, we disaggregate the “low-status” variable for petitioner

advocates and examine the outcomes of pairings with low-status judges.

Figure 11 illustrates these effects, with comprehensive results

presented in Appendix Table A7. The coefficients for “Adv neutral x

Judge low-status” and "Petitioner SC x Judge low-status” consistently

show statistical insignificance, with only one exception: advocates with

caste-neutral names are more 0.8 pp more likely to see their case

allowed. As before, the observed advantages of the advocates are

concentrated among caste-neutral advocates rather than SC advocates. For

respondents, we observe no statistically significant coefficients for

these interaction terms.

A notable finding emerges regarding advocates representing

petitioners: regardless of their caste classification (low-status,

caste-neutral, or Scheduled Caste), they do not appear to face

systematic or widespread discrimination based solely on their names.

This contrasts with the experiences of petitioners themselves. This

phenomenon may be driven by the close working relationships between

lawyers and judges – frequent interactions and the shared identity of

working in the legal profession may supersede caste-based biases

(Bursztyn and Yang 2022). We emphasize however, that we are simply

restricting our attention to filing lawyers.

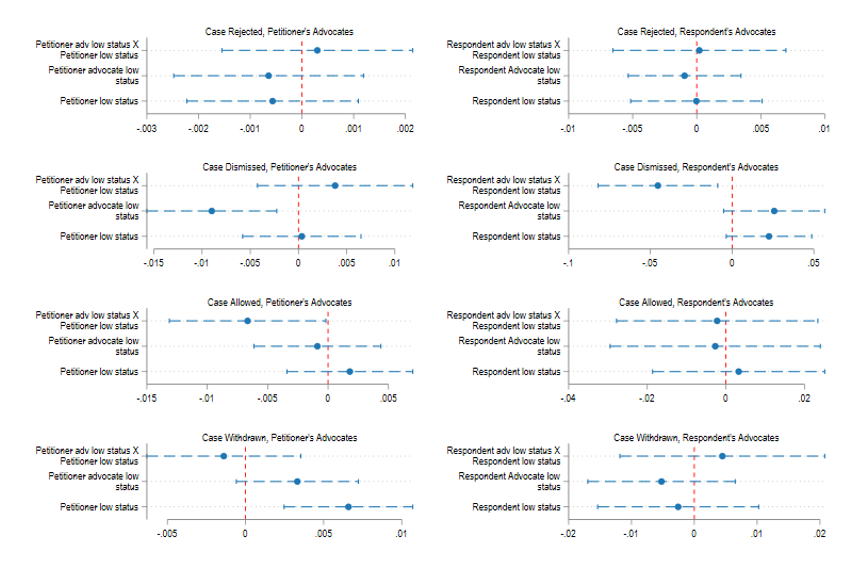

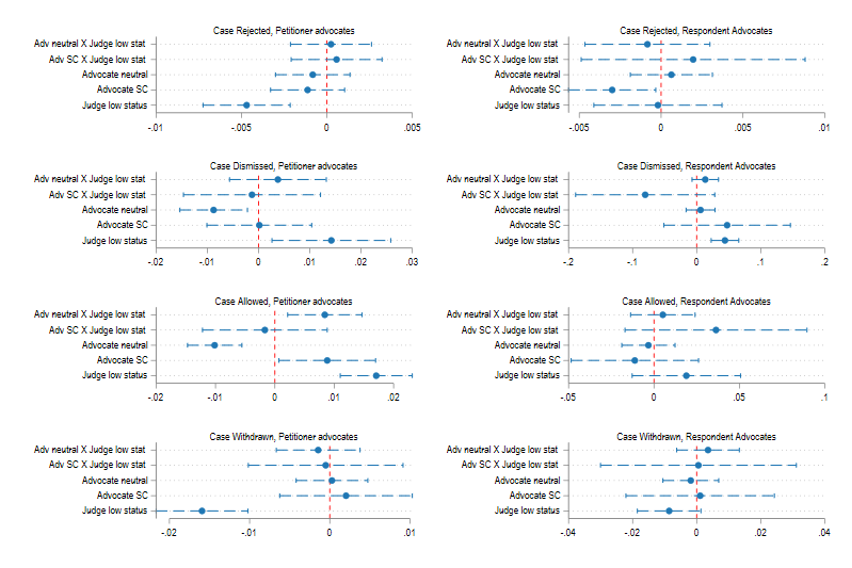

Figure 12. Case outcomes: Matching between

low-status litigants (petitioners and respondents) and advocates on the

basis of identity. Low-status includes both SC and caste-neutral

litigants. Regressions are based on the first observed order for a

specific court case. All regressions control for district, year and the

type of case fixed-effects. Standard errors are clustered at district

and year level. Confidence intervals correspond to 5% statistical

significance.

Figure 13.

Case outcomes: Matching between caste-neutral litigants (petitioners and

respondents) and advocates on the basis of identity. Regressions are

based on the first observed order for a specific court case. All

regressions control for district, year and the type of case

fixed-effects. Standard errors are clustered at district and year level.

Confidence intervals correspond to 5% statistical significance.

Figure 13.

Case outcomes: Matching between caste-neutral litigants (petitioners and

respondents) and advocates on the basis of identity. Regressions are

based on the first observed order for a specific court case. All

regressions control for district, year and the type of case

fixed-effects. Standard errors are clustered at district and year level.

Confidence intervals correspond to 5% statistical significance.

Matching between Litigants and

Advocates

Finally, we examine the consequences of matching between litigants

and advocates. Figure 12 (Appendix Table A10 to Appendix Table A13)

present results. Here we see that for petitioners, low-status

petitioners with a low-status advocate are 0.7 pp less likely to have

their case allowed (and therefore successful) and this coefficient is

significant at the 5% level. Low-status respondents with a low-status

advocate are 4.5 pp more likely to have their case dismissed. None of

the other coefficients are statistically significant. Each of these is a

disadvantage.

Disaggregation of the low-status variable here again illustrates that

these two disadvantages are coming from the caste-neutral group (Figure

13). We note however, one additional result from this analysis. The

coefficient for “Respondent SC x Advocate Low Status” is negative and

significant at the 5% level (b=-0.054, se=0.023) for the "Allowed"

outcome, suggesting that SC respondents who match with low-status

advocates are less likely to see a successful case outcome, presumably a

desired outcome for the respondent. We do not see this advantage for

caste-neutral respondents.

This analysis reveals that status-matching between litigants and

advocates generally results in disadvantages for low-status parties,

particularly among caste-neutral groups. However, a notable exception

emerges for SC respondents paired with low-status advocates, who

experience a decreased likelihood of facing successful cases against

them.

To sum up the results on case outcomes, our analysis reveals subtle

but statistically significant disadvantages for low-status petitioners

and respondents when matched with low-status judges or advocates, with

effects primarily concentrated among caste-neutral parties.

Interestingly, SC respondents paired with low-status advocates

experience a potentially advantageous outcome, showing a decreased

likelihood of facing successful cases against them.

Discussion

Our findings highlight some complex dynamics related to identity and

representation in Bihar's judicial system. Our approach however, has

some important limitations. One significant caveat is that we do not

observe the socioeconomic status or class of the litigants in our data.

Names, while informative, are an imperfect proxy for social identity and

may not fully capture the complex interplay of caste, class, and other

socioeconomic factors that influence judicial outcomes. Additionally,

our analysis does not delve into the content of the cases themselves.

This is an important area of future work.

Another caveat of our analysis is that the observed disparities may

not solely indicate bias within the high court, but also a cascade of

other biases in the legal processes. Instead, they could reflect

disparities in the types of cases initially filed in district courts,

differential treatment of groups at the lower court level, and

subsequent variations in which cases each group chooses to appeal to the

high court.

With these limitations in mind, we can however, cautiously interpret

our results. The first key result is that caste-neutral litigants select

in-community lawyers, though this doesn't consistently improve outcomes

of their cases. Litigants appear to face a quality-identity trade-off in

advocate selection, i.e. they choose lawyers from their own community

even though those lawyers are less likely to produce stronger

outcomes.

Several factors might explain this preference for in-community

advocates. Identity networks can facilitate easier and more

cost-effective access to institutions (Akerlof and Kranton 2002;

Jackson, Rodriguez-Barraquer, and Tan 2012). For marginalized

individuals, who often experience significant social distance from

bureaucratic institutions, navigating India's complex legal system can

be particularly challenging and costly (Krishnan et al. 2014). Evidence

from the United States indicates that in-group lawyers may inspire

greater trust among clients (Ryo 2018; Young and Hassan 2020).

Furthermore, disadvantaged defendants might resist court-appointed

lawyers due to trust issues (Clair 2021). These findings suggest that

the preference for in-community advocates may be driven by factors

beyond mere legal efficacy, including accessibility, cultural

familiarity, and trust.

A second key result of this paper is that we see neither litigants

nor advocates matching with judges on the basis of names. This

corroborates some recent work on random judge assignments in Indian

courts (Chandra, Kalantry, and Hubbard 2023; Ash et al. 2022). We do

however find that even random matching yields modest but nevertheless

significant impacts on judicial outcomes. This is a novel result. It

likely stems from our narrower focus on a single state and our focus on

caste-neutral names within the state. Unlike the studies that examine

the whole country, our algorithm is finely tuned to this specific social

context, enabling us to capture subtle identity effects that broader

studies may overlook.

A final key result of our paper is that litigants with caste-neutral

names appear to be disadvantaged in all their matches, regardless of

whether the matching is coincidental or deliberate. One interpretation

of this is that a caste-neutral name may inadvertently mask systemic

disadvantages faced by a petitioner, potentially absolving judges and

other legal stakeholders from the responsibility of providing necessary

accommodations or considerations for their unique vulnerabilities. This

oversight can lead to a cascading effect of compounded inequalities

throughout the legal process. It is also noteworthy that we do not see

such disadvantages for advocates with caste-neutral names – again, high

levels of contact between lawyers and judges may erode stereotyping,

misperceptions or bias in this population (Bursztyn and Yang 2022).

It is perhaps paradoxical that a practice adopted to reduce caste

salience in Bihar’s formal institutions has potentially established a

new category within the same system. From the perspective of social

movement studies, this finding is perhaps not unexpected: social

movements are known to disrupt existing social orders (in this case,

caste networks) but inadvertently create new social categories that

perform similar roles (Amenta et al. 2010). This phenomenon also serves

as a reminder of the caste system’s fluidity and its persistence even in

ostensibly neutral institutions such as the judiciary (Srinivas 1957;

Deshpande 2011; Jodhka 2017; Munshi 2019).

Overall, our research contributes to the expanding body of literature

on India’s judicial system, challenging the prevailing perception of its

courts as isolated entities detached from societal dynamics (Sen 2017;

Rudolph and Rudolph 2001). While it has been previously noted that

judges and advocates often hail from privileged segments of society

(Gadbois 2011; Galanter and Robinson 2017) and that the court has

improved geographical representation (Chandrachud 2020), there are many

more questions about the dynamics of social identity in shaping outcomes

of India's justice system.

Conclusion

This study analyzes over one million cases at the Patna High Court

over a decade to provide novel insights into the complex interplay

between social identity and judicial processes. We find a high

concentration of last names. We use a machine-learning algorithm to

decode names for markers of caste identity. We find that nearly half of

petitioners and respondents use caste-neutral names.

We test for three hypotheses for matching: (a) Between petitioners

and judges; (b) Between advocates and judges; and (c) Between

petitioners and their advocates. We find minimal evidence of

identity-based matching between judges and litigants or their advocates.

However, we observe significant matching between litigants and their

chosen advocates, particularly among those with caste-neutral names.

This suggests that while the judicial system may strive for impartiality

in case assignments, litigants often seek representation from advocates

with similar social backgrounds.

Finally, we study the impact of matching on outcomes. Here we find

that the use of caste-neutral names by petitioners, while potentially

aimed at mitigating discrimination, is associated with some significant

disadvantages in case outcomes. This paradox suggests that attempts to

conceal caste identity through name changes may inadvertently create new

categories of disadvantage within the legal system.

This research serves as a poignant reminder that courts function as

integral components of the broader societal fabric. Rather than viewing

the legal system in isolation, it is more aptly perceived as a dynamic,

nonlinear superposition of intricate social networks consisting of

people with complex identities. Delving deeper into the complexity of

these relationships in the legal system is a promising avenue for future

research.

Acknowledgments and

Disclosure

We are grateful to Shilpa Rao and Lechuan Qiu for excellent research

assistance. We are also very grateful to Jishnu Das, Jill Grennan,

Carmine Guerriero, Rohit Joshi, Abu Nasar, Vijayendra Rao, Martin

Ravallion, Vikram Raghavan, Vasujith Ram, Nicholas Robinson, Radhika

Pradhan, Mrinal Satish, Petros Sekeris, Sushant Sinha and Nayantara

Vohra for very helpful advice, critical insights and very stimulating

discussions. Peter Neis gratefully acknowledges the support received

from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche of the French

government through the program "Investissements d'avenir"

(ANR-10-LABX-14-01). We are also grateful to the World Bank Research

Support Budget and Georgetown University for financial support. The

findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not

necessarily reflect the views of the World Bank, its Board of Executive

Directors, or the governments they represent.

References

Abramitzky, Ran, Leah Boustan, and Katherine Eriksson. 2020. “Do

Immigrants Assimilate More Slowly Today than in the Past?” American

Economic Review: Insights 2 (1): 125–41. DOI:

10.1257/aeri.20190079

Akerlof, George A, and Rachel E Kranton. 2002. “Identity and

Schooling: Some Lessons for the Economics of Education.” Journal of

Economic Literature 40 (4): 1167–1201. DOI:

10.1257/002205102762203585Amenta, Edwin, Neal Caren, Elizabeth

Chiarello, and Yang Su. 2010. “The Political Consequences of Social

Movements.” Annual Review of Sociology 36 (1): 287–307. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120029

Ash, Elliott, Sam Asher, Aditi Bhowmick, Sandeep Bhupatiraju, Daniel

L Chen, Tatanya Devi, Christoph Goessmann, Paul Novosad, and Bilal

Siddiqi. 2022. “Measuring Gender and Religious Bias in the Indian

Judiciary.” TSE Working Papers 22-1395, Toulouse School of Economics

(TSE).

Banerjee, Abhijit, Marianne Bertrand, Saugato Datta, and Sendhil

Mullainathan. 2009. “Labor Market Discrimination in Delhi: Evidence from

a Field Experiment.” Journal of Comparative Economics 37 (1):

14–27. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2008.09.002

Bayly, Susan. 2001. Caste, Society and Politics in India from the

Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age. Vol. 3. Cambridge University

Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521264341

Berdejo, Carlos, and Daniel L Chen. 2017. “Electoral Cycles among Us

Courts of Appeals Judges.” The Journal of Law and Economics 60

(3): 479–96.DOI: 10.1086/696237

Bertrand, Marianne, and Sendhil Mullainathan. 2004. “Are Emily and

Greg More Employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A Field Experiment on Labor

Market Discrimination.” American Economic Review 94 (4):

991–1013. DOI: 10.1257/0002828042002561

Blair, Harry W. 1980. “Rising Kulaks and Backward Classes in Bihar:

Social Change in the Late 1970s.” Economic and Political

Weekly, 64–74.

Bursztyn, Leonardo, and David Y Yang. 2022. “Misperceptions about

Others.” Annual Review of Economics 14 (1): 425–52.

DOI:10.1146/annurev-economics-051520-023322

Buswala, Bhawani. 2023. “Undignified Names: Caste, Politics, and

Everyday Life in North India.” Contemporary South Asia 31 (4):

567–83. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09584935.2023.2262943

Chakrabarti, Rajesh. 2013. Bihar Breakthrough: The Turnaround of

a Beleaguered State. Rupa Publications.

Chandra, Aparna, Sital Kalantry, and William HJ Hubbard. 2023.

Court on Trial: A Data-Driven Account of the Supreme Court of

India. Penguin Random House India.

Chandrachud, Abhinav. 2020. The Informal Constitution: Unwritten

Criteria in Selecting Judges for the Supreme Court of India. Oxford

University Press. DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198098560.001.0001

Chen, Daniel L, Tobias J Moskowitz, and Kelly Shue. 2016. “Decision

Making under the Gambler’s Fallacy: Evidence from Asylum Judges, Loan

Officers, and Baseball Umpires.” The Quarterly Journal of

Economics 131 (3): 1181–1242. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjw017

Clair, Matthew. 2021. “Being a Disadvantaged Criminal Defendant:

Mistrust and Resistance in Attorney-Client Interactions.” Social

Forces 100 (1): 194–217. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soaa082

Clark, Gregory. 2014. “The Son Also Rises.” In The Son Also

Rises. Princeton University Press.

Clark, Gregory, and Neil Cummins. 2015. “Intergenerational Wealth

Mobility in England, 1858–2012: Surnames and Social Mobility.” The

Economic Journal 125 (582): 61–85. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12165.

Cook, Lisa, Trevon Logan, and John Parman. 2016. “The Mortality

Consequences of Distinctively Black Names.” Explorations in Economic

History 59:114–25. DOI: 10.1086/722093

Dar, Aaditya, and Abhilasha Sahay. 2018. “Designing Policy in Weak

States: Unintended Consequences of Alcohol Prohibition in Bihar.”

Available at SSRN 3165159.

Das, Veena, and Jacob Copeman. 2015. “Introduction. On Names in South

Asia: Iteration,(Im) Propriety and Dissimulation.” South Asia

Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, no. 12. DOI:

10.4000/samaj.4063

Deshpande, Ashwini. 2011. The Grammar of Caste: Economic

Discrimination in Contemporary India. Oxford University Press. DOI:

10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198072034.001.0001

Deshpande, Ashwini, and Katherine Newman. 2007. “Where the Path

Leads: The Role of Caste in Post-University Employment Expectations.”

Economic and Political Weekly, 4133–40.

Dirks, Nicholas B. 1989. “The Invention of Caste: Civil Society in

Colonial India.” Social Analysis: The International Journal of

Social and Cultural Practice, no. 25, 42–52.

Diwakar, R. Ramachandra. 1959. Bihar through the Ages. 44.

Orient Longmans.

Fan, Xiaohui, Yuan Gao, Yan Liu, Xiaomeng Li, Yida Yuan, Liujun Chen,

and Jiawei Chen. 2024. “A Study of the Spatial Distribution

Characteristics of Chinese Surnames.” American Journal of Human

Biology, e24073. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.24073

Fisman, Raymond, Daniel Paravisini, and Vikrant Vig. 2017. “Cultural

Proximity and Loan Outcomes.” American Economic Review 107 (2):

457–92. DOI: 10.1257/aer.20120942

Gadbois, George H. 2011. Judges of the Supreme Court of India:

1950–1989. Oxford University Press. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198070610.001.0001.

———. 2018. Supreme Court of India: The Beginnings. Oxford

University Press.

Galanter, Marc, and Nick Robinson. 2017. “Grand Advocates: The

Traditional Elite Lawyers.” The Indian Legal Profession in the Age

of Globalization, 455. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316585207.014

Gebauer, Jochen E, Mark R Leary, and Wiebke Neberich. 2012.

“Unfortunate First Names: Effects of Name-Based Relational Devaluation

and Interpersonal Neglect.” Social Psychological and Personality

Science 3 (5): 590–96. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550611431644

Gidla, Sujatha. 2017. Ants among Elephants: An Untouchable Family

and the Making of Modern India. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Greif, Avner, and Guido Tabellini. 2017. “The Clan and the

Corporation: Sustaining Cooperation in China and Europe.” Journal of

Comparative Economics 45 (1): 1–35. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2016.12.003

Hoff, Karla, Mayuresh Kshetramade, and Ernst Fehr. 2011. “Caste and

Punishment: The Legacy of Caste Culture in Norm Enforcement.” The

Economic Journal 121 (556): F449–75. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2011.02476.x

Hoff, Karla, and Priyanka Pandey. 2006. “Discrimination, Social

Identity, and Durable Inequalities.” American Economic Review

96 (2): 206–11. DOI: 10.1257/000282806777212611

Hull, Matthew S. 2012. “Documents and Bureaucracy.” Annual Review

of Anthropology 41 (1): 251–67. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.012809.104953

India, Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner of.

2011. Table A-11 Appendix: District Wise Scheduled Tribe Population

(Appendix), Bihar - 2011. Census of India.

Jackson, Matthew O, Tomas Rodriguez-Barraquer, and Xu Tan. 2012.

“Social Capital and Social Quilts: Network Patterns of Favor Exchange.”

American Economic Review 102 (5): 1857–97. DOI:

10.1257/aer.102.5.1857

Jaffrelot, Christophe. 2010. Religion, Caste, and Politics in

India. Primus Books.

Jaffrelot, Christophe, and Sanjay Kumar. 2012. Rise of the

Plebeians?: The Changing Face of the Indian Legislative Assemblies.

Routledge.

Jayaraman, Raja. 2005. “Personal Identity in a Globalized World:

Cultural Roots of Hindu Personal Names and Surnames.” The Journal of

Popular Culture 38 (3): 476–90. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3840.2005.00124.x

Jodhka, Surinder S. 2017. Caste in Contemporary India.

Routledge India. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203701577

Joshi, Shareen, Nishtha Kochhar, and Vijayendra Rao. 2018. "Are Caste

Categories Misleading? The Relationship between Gender and Jati in Three

Indian States". In: Towards Gender Equity in Development,

Edited by Anderson, S., Beaman, L. and JP, Platteau Oxford University

Press. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198829591.001.0001

———. 2022. “Fractal Inequality in Rural India: Class, Caste and Jati

in Bihar.” Oxford Open Economics 1(1): 1-13. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1093/ooec/odab004

Krishnan, Jayanth K., Shirish N. Kavadi, Azima Girach, Dhanaji

Khupkar, Kilindi Kokal, Satyajeet Mazumdar, Nupar, Gayatri Panday,

Aatreyee Sen, Aqseer Sodhi & Bharati T. Shukla, 2014, "Grappling at

the Grassroots: Access to Justice in India's Lower Tier", 27 Harvard

Human Rights Journal 151. Available at:

https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub/1302Kumar, Sanjay. 2018.

Post-Mandal Politics in Bihar: Changing Electoral Patterns.

Vol. 1. SAGE Publishing India.

Mazzarella, William. 2015. “On the Im/Propriety of Brand Names.”

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, no. 12. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.4000/samaj.3986

Menski, Werner F. 2006. Comparative Law in a Global Context: The

Legal Systems of Asia and Africa. Cambridge University