Article History Submitted 11 June 2024. Accepted 11 November 2024. Keywords systematic case law analysis, content analysis, judicial decision-making, accountability, best practices |

Abstract As systematic case law analysis becomes more extensive and intricate as an approach to doing legal research, the need to justify the methods and techniques used for data collection, selection, and analysis grows correspondingly. Without such methodological accountability, the reliability and replicability of this type of legal (empirical) research are compromised, undermining their contribution to legal scholarship and practice. This article investigates the methodological accountability in systematic case law analysis. We conducted an empirical study to evaluate how researchers in the Netherlands account for their processes of collecting, selecting, and analyzing legal decisions and opinions of dispute resolution bodies. Our meta-analysis of systematic case law analysis encompasses 105 academic studies that utilize systematic case law analysis, providing an overview of the current state-of-the-art in the Netherlands. Based on the findings of our case study, we offer best practice guidelines for ensuring methodological accountability in systematic case law analysis. |

|---|

The accessibility of case law in digital collections, databases and repositories has proven itself to be fertile ground for the development of a new approach to doing legal research. Software, AI tools and other computer-assisted data science techniques now enable scholars to collect and study large numbers of judicial decisions and systematically analyze their content using a wide variety of methods (Chen 2019, Dyevre 2021a, Livermore and Rockmore 2019, Medvedeva, Vols and Wieling 2020, Schepers et al. 2023). Conducting this type of research, which deviates from the traditional approach in legal doctrinal research (McCrudden 2006, Hutchinson and Duncan 2012, Smits 2017), requires increased attention to methodological accountability. As systematic case law analysis grows in scope and complexity, so does the need to account for the methods and techniques used for collection, selection and analysis. Without such justification, the reliability and replicability of the study cannot be ensured, and the value of this approach to legal research and scholarship is likely to remain untapped.

In this article, we aim to study the methodological accountability of systematic case law analysis. To this end, we will conduct an empirical study to assess how researchers engaging in this type of analysis account for the ways in which they have collected, selected and analyzed the content of legal decisions and opinions by dispute resolution bodies. To answer this question, we will study recent academic publications in the Netherlands that employ this type of analysis (n=105). Prior research indicates that systematic case law analysis is gaining popularity among Dutch (legal) scholars but is still in its infancy when it comes to providing methodological accounts of the research design and analysis employed (Tijssen 2009, 125–126 and 132–133; Vols and Jacobs 2017, 99 and 104; Verbruggen 2021b, 15–18). In the Netherlands, there has been a well-established debate around the methodology of legal research for two decades now (see Section 3.1 for more details). In addition, considerable attention and government funding has been devoted to the field of Empirical Legal Studies (ELS), in which systematic case law analysis is regularly deployed as an approach to (legal) research. Taken together, these circumstances make the Netherlands a promising case study for exploring questions of methodological accountability in systematic case law analysis.

This article is structured as follows. In Section 2, we discuss the epistemological foundations of systematic case law analysis, thereby situating this approach to doing legal research in international literature and its intersections with both doctrinal legal research and ELS. In Section 3, we present our own method of collecting, selecting and analyzing studies that involve systematic case law analysis in the Netherlands. The results of this qualitative content (meta-)analysis are discussed in Section 4. We conclude the article in Section 5 by offering best practice guidance for methodological accountability in systematic case law analysis.

In this article, we define systematic case law analysis to concern studies that employ social science research methods and techniques to systematically investigate decisions and opinions of dispute resolution bodies. This type of analysis is therefore not a research method per se, but an umbrella term for the application of multiple social science methods in the analysis of case law. Those methods can be qualitative or quantitative in nature, partly depending on the research objective and the number of cases analyzed. The extent to which the methods are supported by software or data science techniques (e.g. topic modelling or large language models) also varies. However, what binds the various research methods of analysis together is that they all aim at systematically collecting, selecting, coding and analyzing text of courts, arbitrators, disciplinary boards or other sorts of dispute resolution bodies (Levine 2006, 285; Hall and Wright 2008, 64; Verbruggen 2021b, 10).

In the last 15 years, a rich literature addressing methodological questions around designing and conducting systematic case law analysis has developed. The first and most widely cited publication on this topic is the article by Hall and Wright (2008), in which the authors analyzed 134 research projects that systematically coded the content of judicial opinions. Based on this analysis, they distinguished best practices for this type of legal (empirical) research. Other scholars have further explored the methodological aspects of systematic case law analysis in subsequent publications (e.g. Brook 2022a; Burton 2017; Salehijam 2018; Schebesta 2018; Verbruggen 2021; Vols and Jacobs 2017), adding to the approaches legal researchers may use to systematically study case law and other legal texts. There are also examples of studies in which a systematic case law analysis is conducted, but which also discuss in detail the methodological aspects of the method used (e.g. Edwards and Livermore 2009; Hunter, Nixon and Blandy 2008; Kastellec 2010; Oldfather, Bockhorst, and Dimmer 2012; Ratanen 2017, Schepers et al. 2023). Studying this body of literature, several important epistemological foundations of systematic case law analysis can be discerned. We outline these in the remainder of this section, starting with the design and objectives of research.

The first stage of systematic case law analysis is the same as the initial stage of most other forms of research. It is important to develop a clear research design in which a research problem is identified, a research question is formulated, and a theoretical framework is developed (Vols and Jacobs 2017, 93; Epstein and King 2002, 54–76). In addition, the research question must not only be an interesting topic for research, but it must also be suitable for answering by means of systematic case law analysis (Salehijam 2018, 36). The literature identifies several research objectives that scholars seek to attain through systematic case law analysis.

First, data collection is mentioned as an important and self-contained research objective (Epstein and King 2002, 20–24). The legal world produces an enormous amount of case law every day, and all of these judicial decisions are archived in one way or another (physically or digitally). Before these archives can be used for scientific purposes, it is important to collect, retrieve, scrape, translate or clean the data so that it can be used by researchers. Although most researchers do not collect data for the sake of collecting data and have other goals in mind, Epstein and King (2002, 24) emphasize that data-collection efforts are important contributions to the scholarly community in their own right and that we should fully recognize them as such. This is especially true when large databases are created that are so rich in content that they can be accessed by multiple users, even those with different projects.

Summarizing data can be seen as a second objective of systematic case law analysis (Epstein and King 2002, 24–29; Hall and Wright 2008, 85–87). Particularly when dealing with large datasets, it can be useful to use data summaries rather than presenting data in their original raw form. Legal scholars often use simple statistical calculations such as the mean, median, mode, range and standard deviation (see also Section 4). Data summaries can also play an important role in qualitative empirical research, where “descriptions can take the form of a verbal summary, for example, when a researcher attempts to summarize whatever precedent (which may include two, three, or many more cases) is relevant to his or her concerns” (Epstein and King 2002, 25). According to Hall and Wright (2008, 87) research projects that analyze the bare outcomes of cases rather than the content of the opinions “do not capture the method's full potential to study the legal content of judicial opinions”. Describing observations through summaries is therefore often not the primary aim of research projects.

The most frequently cited goal of systematic case law analysis is to map out the characteristics of judicial decisions and opinions in a large group of cases to find overall trends or patterns. This third objective is stated in various publications in slightly different terms. For example, it is mentioned that the systematic analysis of case law may aim to document trends in the case law and the factors that appear important to case outcomes (Hall and Wright 2008, 87) or identify factors that can explain variation among cases (Brook 2022a, 107). Again others note that the goal is to identify and to account for variation in outcomes among cases that address a common issue (Levine 2006, 286), or to map connections, patterns or developments (Verbruggen 2021b, 9). The researcher undertaking the analysis is typically interested in specific legal or non-legal elements reflected in the text of the cases. Depending on how and to what extent these aspects emerge in the analysis, the researcher may uncover lines of thought or trends in judicial reasoning (Verbruggen 2021b, 9).

A fourth objective of conducting systematic case law research may be to draw causal inferences. Epstein and King (2002, 29) describe such inference as “the process of using the facts we know to learn about facts we do not know”. In this context, the aim is to establish “whether one factor or set of factors leads to (or causes) some outcome” (Epstein and King 2002, 34). Perhaps the most ambitious application of this type of research is to study the factors that determine the outcomes of cases. This approach of research has come to be known as ‘jurimetrics’, although the term does not seem to be used much nowadays (Vols and Jacobs 2017, 91). Researchers in this tradition use sophisticated forms of statistics to try to model or predict the outcomes of legal proceedings (Hall and Wright 2008, 94–100). Since the objective is more specific than drawing causal inferences, we identify jurimetrics as a separate, fifth research objective of systematic case law analysis.

According to Hall and Wright (2008, 88) researchers who conduct systematic case law analysis aim primarily for descriptive, analytical or exploratory goals. However, in some studies, this kind of research can also have a normative element, for example when the legal correctness of judicial opinions is evaluated (Hall and Wright 2008, 89). According to Brook (2022a, 107) systematic case law analysis can address “evaluative research questions”. Verbruggen (2021b, 9) and Vols (2021, 137–38) also argue that systematic case law analysis can be the prelude to legal theory building, as well as offering opportunities to test normative views on how the law should be.

Lastly, an objective of systematic case law analysis often mentioned is falsifying (empirical) claims in academic literature, case law, or in government or regulatory policies (e.g. Brook 2022a, 108). Systematic analyses allow scholars to verify or refute the implicit or explicit empirical claims about case law which persist in academic literature or legal practice. Hall and Wright (2008, 84) recognize this further goal of myth busting by noting: “scholars have found it especially useful to code and count cases in studies that debunk conventional legal wisdom. Content analysis works well in this setting because it highlights the methodological weakness of traditional legal analysis; that is, this method can simultaneously demonstrate the error of a conventional view and explain how it became the convention.”

Hall and Wright (2008, 79), and those following in their footsteps (see e.g. Brook 2022a, 110; Salehijam 2018, 36; Vols and Jacobs 2017, 94–97) distinguish three principal stages that systematic case law analysis comprises: “(1) selecting cases; (2) coding cases; and (3) analyzing the case coding”. It is vital that the guidelines of existing social science methods are respected at the various stages of a research project. Sound empirical research must meet the requirement of replicability: “another researcher should be able to understand, evaluate, build on, and reproduce the research without any additional information from the author” (Epstein and King 2002, 38). In that perspective, Hall and Wright (2008, 64) stress that: “content analysis is more than a better way to read cases. It brings the rigor of social science to our understanding of case law, creating a distinctively legal form of empiricism.”

The systematic collection of judicial decisions is the first stage of analysis. When collecting cases, the requirement of replicability is particularly important: other researchers should be able to repeat the research and find the same set of judgments (Vols and Jacobs 2017, 94; Hall and Wright 2008, 105–106). Hence, it is important to provide a clear explanation of the specific search strategy that includes, for example, the location of the case law (physical archive or digital database), the search terms, the period during which the search is carried out and other search criteria. During this stage, it should also be determined whether the entire population or a (representative) sample is included in the study. The population refers to all cases in a specified time frame about which the researcher would collect information if time and resources were unconstrained (Epstein and King 2002, 99–100). If it is not possible to include the entire population, a study sample (i.e. a part of the population that is included in the study) should be generated, using methods of random sampling to avoid selection bias (Hall and Wright 2008, 102).

The second stage involves the reading and coding of the selected judicial decisions and opinions. The term coding refers to recording the relevant variables of each judicial decision in such a way that systematic analysis becomes possible (e.g. Epstein and Martin 2014, 911, Miles, Huberman and Saldaña 2014, 71–72). Epstein and King (2002, 65) describe variables as “characteristics of some phenomenon that vary across instances of the phenomenon”. Coding is frequently done manually, but this can also be automated (e.g. Oldfather, Bockhorst and Dimmer 2012). When coding case law, a wide range of variables can be coded. Which coding is applied depends on the research design and research question. Examples of variables that can be coded include the parties’ identities and attributes, the types of legal issues raised and in what circumstances, the basic outcome of the case or issue, and the bases for decision (Hall and Wright 2008, 107). Vols and Jacobs (2017, 95) note that some researchers prepare the coding scheme in an inductive way: they first read a part of the case law, then establish the various variables and then start coding. Other researchers take a more deductive approach: they establish the various variables beforehand—based on the theoretical framework—and then start coding the case law. It is common to use a combination of deduction and induction (Hall and Wright 2008, 107, Epstein and Martin 2014, 911). In this approach, code development is an iterative process, using a tentative set of coding categories and refining these categories through pilot testing, revision and finetuning.

The testing of the reliability of the coding, its categories and description is considered key. There are several reliability tests that can be used, depending on how many researchers (one or more) were involved in the coding process. Intra-coder reliability allows researchers working individually to test the consistency of their coding at different time intervals. Inter-coder reliability tests the level of consistency of coding between two or more coders (Schreier 2012, 192). Both tests translate into a statistical measure, of which a common one is Cohen’s kappa. Ranging from 0 to 1, this kappa score indicates the degree of agreement between the time or person of coding by chance alone, with 0 being the agreement entirely based on chance and 1 indicating perfect agreement (Hall and Wright 2008, 113–114).

The final step consists of analyzing and presenting the data. How to do this is again defined by the research design, the research question and the methods employed (Hall and Wright 2008, 117–118, Vols and Jacobs 2017, 96–97). If, for example, a quantitative study using linear regression analysis was conducted, the standard deviation and its mean can be demonstrated by using tables, diagrams or graphs. Alternatively, a qualitative study that classifies different argumentation structures used by courts may rely on cross-case analysis (Miles, Huberman and Saldaña 2014, 100 et seq) and use flowcharts or decision trees to present the constellation of these arguments (Wijntjens 2021). Often, however, the presentation of the findings of systematic content analysis involves descriptive and text-based accounts on the patterns and trends found, the myths busted, and the explanations for just that.

Conducting a systematic analysis of case law is very similar to what the traditionally trained legal scholar does when examining a series of court decisions on a particular legal rule or doctrine. Hall and Wright (2008, 64) aptly describe this similarity as follows:

On the surface, content analysis appears simple, even trivial, to some. Using this method, a scholar collects a set of documents, such as judicial opinions on a particular subject, and systematically reads them, recording consistent features of each and drawing inferences about their use and meaning. This method comes naturally to legal scholars because it resembles the classic scholarly exercise of reading a collection of cases, finding common threads that link the opinions, and commenting on their significance.

While there is a strong resemblance with traditional, doctrinal legal research, it must be stressed that this type of research is also indispensable when it comes to the proper positioning and appreciation of systematic case law analysis. Vols (2021, 137–138) stresses the fundamental importance of the theoretical legal framework (often a legal rule and/or doctrine) for both the focus and design of the analysis, and for interpreting the relevance of the insights found for theory and practice. Peeraer and Van Gestel (2021, 189) similarly argue that such analysis is by no means a substitute for, but a much-needed complement to traditional interpretive forms of research in jurisprudence and judicial law-making. In their view, systematic case law analysis lends itself first and foremost to the study in the breadth of the research object, rather than in its depth. The empirical results of the analysis can be explained, interpreted or falsified using legal interpretation methods, such as the grammatical, law systematic and teleological interpretation techniques. Such methods and techniques can also be employed to further explore the meaning of the patterns uncovered.

Systematic analysis of judicial decisions and opinions can also be placed in the tradition of ELS, in which data obtained from observations of reality (the empiricism) is used to study the law (Smit et al. 2020, 11–12; Van de Bos 2021, 19). ELS stresses the systematic collection and analysis of empirical data around the law in accordance with generally accepted methods and techniques, which can be both qualitative and quantitative (e.g. Cane and Kritzer 2010, 4; Epstein and Martin 2014, 3). Regarding the application of empirical-legal research, a distinction is made between three interrelated pillars: (1) research on the assumptions underlying the law; (2) research on how the law functions in practice; and (3) research on the effects of the law (Bijleveld 2023, 5–7). The object of empirical legal research is thus the observable world of law and the actors, processes and circumstances involved in it. Case law and other forms of dispute resolution are part of this realm, and for this reason systematic case law analysis can be classified as a form of ELS.

Whether traditional case law analysis is empirical research is subject to methodological debate. Although this type of research is traditionally qualified as legal dogmatic research, there are also several researchers who qualify it as empirical research. According to Epstein and King (2002, 2–3):

[t]he word ‘empirical’ denotes evidence about the world based on observation or experience. […] Under this definition of ‘empirical,’ assertions that ‘the amount of theoretical and doctrinal scholarship ... overwhelms the amount of empirical scholarship,’ ring hollow. As even the most casual reader of the nation’s law reviews must acknowledge, a large fraction of legal scholarship makes at least some claims about the world based on observation or experience.

Similarly, Van Dijck, Snel and Van Golen (2018, 96) write that “case law analysis, strictly speaking, also classifies as observing reality” and can therefore be called empirical research.

We must acknowledge, however, that the debate on whether systematic case law analysis is empirical legal research, is not a very fruitful one (cf. Van Boom, Desmet and Mascini 2018, 8). Some scholars indeed argue that this type of research holds a middle ground between traditional doctrinal research and empirical legal scholarship (Brook 2022a, 110; Oldfather, Bockhorst and Dimmer 2012, 8). Verbruggen (2021b, 18) also emphasizes that systematic case law analysis has the potential to link traditional and empirical legal research:

On the one hand, classical legal scholars use this type of research to develop their critical capacity by studying case law differently and to account for it following existing conventions and ground rules of social science research. On the other hand, systematic case law analysis compels empiricists to embed the research they have undertaken in law and in legal doctrines. Indeed, without such theoretical embedding, their research runs the risk of providing answers to questions that are irrelevant to law and legal practice.

No matter how one classifies systematic case law analysis, its methodological accountability must be sound. To what extent that is the case in analyses carried out in the Netherlands, we will analyze in the remainder of this article.

In the last two decades, a rich debate around methodological accountability of legal research has developed in the Netherlands. The debate was sparked by the later Dean and Rector of Leiden University, Professor Carel Stolker (2003) in a tantalizing essay titled ‘Yes, learned you are’. In this essay, he argued that while legal scholars know a lot, they should pay much more attention to the scientific character of academic legal research. Explanations for why the debate on the methodology of legal research emerged so fiercely after Stolker’s essay include the increased attention for international research collaborations, rankings and reviews at Dutch Law Faculties, the rise of multidisciplinary research in the legal field, as well as the growing need to apply for competitive research grants that are open to researchers in various domains of social science and humanities (Smits 2009; Stolker 2014; Vranken 2014). In all cases, legal scholars are pushed to explain what they do and how they operate.

As in other countries, case law analysis has been one of the most prominent trades used by legal scholars in the Netherlands. However, when it comes to providing an account of the ways in which they selected and analyzed cases, their readership is often left in the dark about how they went about their business. A prominent law professor at Leiden University bluntly admitted that PhD candidates regularly ignore unwelcome court decisions in their dissertations (Nieuwstadt and Van Schagen 2007, 923–924). In further discussing and rationalizing the apparent acceptance of this perhaps bewildering practice in Dutch legal scholarship, Vranken (2009) points out that many methodological choices made by legal scholars remain implicit. An empirical review of 90 PhD dissertations in law by Tijssen (2009) confirms this lack of methodological accountability for case law analysis in legal scholarship. While case law was used as a source for research in some 75% of Tijssen’s sample, less than 50% contained an explicit account of how the sources were selected and used, and it was unclear whether this account could be found in the dissertation at all (Tijssen 2009, 125–126). Moreover, only 1/3 of the dissertations contained an explanation of how the analysis of the sources was carried out (Tijssen 2009, 131–132).

Tijssen sought to explain these results by discussing them with a panel of experts. The consulted experts considered the results to match the nature of doctrinal legal research. First, in this type of research, it is rather straightforward to determine which case law is relevant or irrelevant to a particular research question. It would be ‘stating the obvious’ if PhD candidates were to explicitly account for their selection of case law. Second, this type of research has the implicit aim of completeness, which implies that all sources relevant to the research topic (including case law) are studied (Tijssen 2009, 146–147). If a different approach was taken, there would be a clear need to explicitly account for that approach.

A systematic case law analysis of the kind discussed in this article would qualify for such a different approach. However, even for this type of legal research established methodological guidelines have been hard to come by in the Netherlands. Vols and Jacobs (2017, 90) signaled that: “methodological-based guidance on how students and more experienced legal researcher can use to study Dutch case law is lacking currently”. To provide such guidance for quantitative analysis of judicial decisions, Vols and Jacobs collected and reviewed all relevant case law analyses published in Dutch academic legal journals over a period of approximately 10 years (January 2006 and July 2016). They assessed 22 publications, and coded the legal fields, court levels involved, sample size, methods used for data collection, selection and analysis, and the methods literature referenced. Interestingly, they found that:

Scholars rarely make clear how they have trained themselves in doing the systematic analysis, what methodological literature they relied on for that purpose, and to what methodological school of thought they relate;

Only some of the publications clearly describe the search terms or selection criteria used for data collection;

Only one study involved the (random) sampling of cases;

15 out of 22 publications do not provide information on how the cases were coded, either in terms of the variables used for coding, the number of researchers involved in the coding, and how they sought to prevent coding mistakes.

In again 15 out of 22 publications, no advanced (statistical) methods of analysis were used; the rest concern the simple ‘counting’ of variables, in numbers or percentages.

50% of the publications appeared in the last three years of the period studied, suggesting that this type of analysis is becoming increasingly popular.

Based on these findings, Vols and Jacobs conclude that there are many methodological aspects that can be improved in the Dutch state-of-the-art in quantitative case law analysis. They note that: “Many of the studies provide a poor accountability of data collection and the research methods used. This makes it possible to question the replicability, but also the reliability of many of the results.” (Vols and Jacobs 2017, 100).

Triggered by these methodological concerns, and the opportunities and risks created by new data science tools, including artificial intelligence (AI) for systematic case law analysis, Verbruggen brought together 11 scholars from Belgium and the Netherlands to discuss a variety of methodological approaches to legal research in which case law is systematically analyzed (Verbruggen 2021b). The edited volume provides insights into the methodological questions of both quantitative and qualitative systematic case law analysis by discussing the possibilities and limitations of the applied methodologies for legal research. This book has further contributed to raising awareness of the importance of methodological accountability for systematic case law analysis.

In this case study, we aim to analyze the current state-of-the-art of systematic case law analysis in the Netherlands.3 More specifically, we will study the ways in which scholars account for the methodological choices regarding data collection, selection and analysis in systematic case law analyses. As such, we seek to answer the question of how researchers in the Netherlands provide methodological accountability in this specific type of legal research.

To that end, we have conducted a systematic content analysis of systematic case law analyses in the Netherlands. We have carried out a systematic literature review to assess the content and methodological approach of academic studies (articles, books, book chapters, dissertations, commissioned scientific reports) published in Dutch between 2016 and 2023 which involved a systematic analysis of legal decisions and opinions by dispute resolution bodies relevant to Dutch law and legal practice. These bodies involve courts, disciplinary bodies for regulated professions and alternative dispute resolution institutions. Following Hall and Wright (2008, 71), we looked to include only studies “that coded for legal, factual, analytic, or linguistic elements of legal decisions that could be gleaned only by a close reading of the opinions, rather than, for instance, information available in a digest or abstract of the decision.” In other words, our dataset comprises those studies in which the authors held themselves out to conduct a systematic analysis of the content of legal decisions and opinions. The analysis can be qualitative or quantitative (or both) in nature. Accordingly, we will assess how this type of legal research has developed since the review of Vols and Jacobs (2017), and to what extent their methodological concerns as well as those flagged by others (e.g. Tijssen 2009, Verbruggen 2021a) have been effectively addressed.

To collect the relevant academic studies we used Google Scholar, Worldcat, and the platform of LegalIntelligence. The latter is a subscription-based digital platform that is frequently used by legal practitioners and researchers in the Netherlands. It operates as a portal to search the digital collections of all major Dutch legal publishers. We used (a combination of) the following search terms (as translated in English) to retrieve from the system: ‘systematic’, ‘structured’, ‘case law’, ‘jurisprudence’, ‘analysis’, ‘research’, ‘qualitative’, ‘quantitative’ and ‘statistics’. We also used Boolean operators (AND, Quotation marks “”, and Asterisk *) to fine-tune the searches. The searches were carried out between January and May 2024, either by the authors or our research assistant. All searches and results were logged.

We selected only studies that were written in Dutch and whose authors have their principal affiliation at a research institution in the Netherlands. To see whether the search results matched the selection criteria specified above, all results were subjected to a quick scan. By doing so, we identified some 150 academic studies that potentially qualified as relevant for our case study. Upon closer reading of these results, we found that several studies did not meet our selection criteria. Others were closely related to other systematic analyses by the same author(s). We decided to remove these results from our dataset, selecting only the study that was most elaborate in its methodological approach. In other cases, a result would report a study involving the analyzing of judicial decisions and opinions. Using the method of snowballing (Snel and Garcias de Moraes 2017, 52), we closely read the referenced study and included it in the dataset whenever meeting the selection criteria. When completing this intense collection and selection process, we amassed a total of 105 unique academic studies in our dataset.

To systematically analyze these 105 studies, we used a comprehensive MS Excel-based coding scheme. Using the guidance on coding strategies in Schreier (2012) and in Miles, Huberman and Saldaña (2014), we developed this scheme in three rounds of coding. In the first round, we randomly selected 10 studies and read these closely to identify as many indications as possible as to how the authors explained the collection, selection and analysis of the legal decisions and opinions. This inductive approach led to a provisional list of codes. As a second step, this list was supplemented by variables that we had gathered from the literature we studied on systematic case law analysis (Sections 2 and 3.1). In particular, the cited work of Hall and Wright (2008) and Vols and Jacobs (2017) helped to organize the codes in the themes and headings. Accordingly, our coding scheme was constructed using both inductive and deductive approaches (Miles, Huberman and Saldaña 2014, 81). As a third step, we each coded five studies to see whether the descriptions of the variables in the scheme were clear and comprehensive. After discussing our experiences and finetuning the codes, code descriptions and coding rules,4 we finalized the coding scheme.

We then tested the coding scheme for validity across different coders. To that end, we trained our research assistant to use the coding scheme. This training involved the close reading of previously identified search results (in part retrieved by our assistant), the coding of in total ten studies, and discussions on how this coding compared to the coding of one of us. After the training, we and the research assistant coded the same seven studies. This intercoder reliability test revealed a high agreement percent (91.12%), suggesting that the coding scheme was robust and could lead to valid and reproduceable results.5

After this check, all studies were coded in June 2024, each of us coding roughly half of the dataset. During the coding period, each of us took notes and added comments to the coding scheme regarding interesting or peculiar aspects of the studies analyzed, as well as to best practices. In our previous experience (Verbruggen 2021c, 82–86; Wijntjens 2021), these annotations prove invaluable in conducting intermittent discussions about the data, identifying patterns during the coding process, and in structuring the analysis in later stages of the research.

What results did our meta-analysis of systematic case law analyses in the Netherlands yield? We present the results in four parts: (4.1) use, scope and purpose of systematic case law analysis; (4.2) data collection and selection; (4.3) coding and (4.4) data analysis. We discuss these results against the background of the methodological literature discussed in Sections 2 and 3.1.

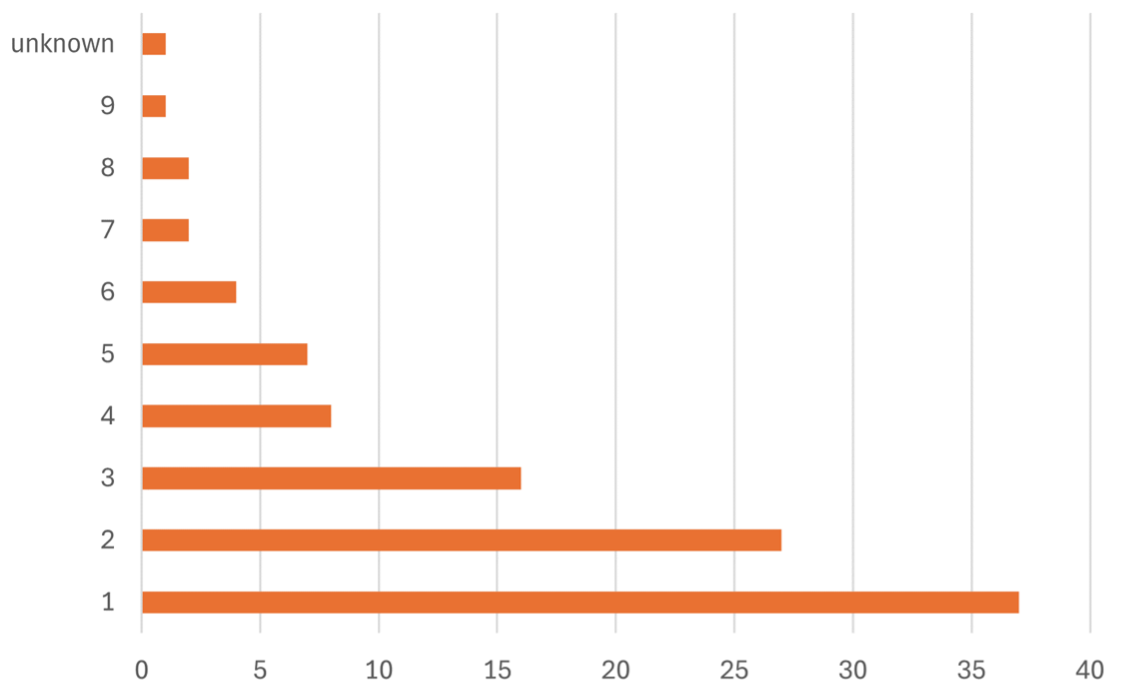

Our sample of systematic case law analysis (n=105) spans a period of eight years (2016–2023). This amount is significantly higher than the number of studies Vols and Jacobs (2017) identified for the period of ten years (n=22 in 2006–2016). While that difference can be explained by the slightly broader scope of our meta-analysis (also accounting for only qualitative studies, n=21), we are confident to say that systematic case law analysis in the Netherlands is on the rise. Figure 1 shows the number of studies published in each year of the period under review.

About two-thirds of the studies (n=71) have been published in the last four years of the period studied. Although a steady trend indicating the increased use of systematic case law analysis cannot be discerned, this type of research has certainly grown further in popularity since the analysis of Vols and Jacobs (2017).

Figure 1. Studies published each year.

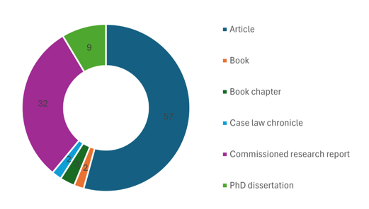

Figure 2 shows the type of publication in which systematic case law analysis is presented. It demonstrates that articles are the most popular sort of publication in which this type of research is presented (n=57, 54%), followed by commissioned research reports (n=32, 30%). Figure 3 shows the number of authors involved in the studies. That number varies between 1 and 9, while in one publication the number could not be retrieved. Single-authored publications represent 35% of the sample, while joint publications account for 65%. Our analysis also indicates that if more than two authors are involved in the publication (n=35), the publication type is more likely to be a book or a commission research report (25/35=71%) rather than an article (13/35=29%). These findings suggest that systematic case law analysis is often an effort of team science. However, as Verbruggen (2021, 25) noted, this also invites the question of how the authors involved sought to ensure the reliability of their coding scheme and the validity of their findings (see below at Section 4.3).

Figure 2. Type of publication.

Figure 3. Number of authors involved.

We also coded whether the systematic case law analysis is part of a wider research that employs other social science methods (e.g. interviews, surveys, vignette studies, et cetera). In 38% of the studies that was the case. These studies were most frequently published as ‘large’ publications, i.e. as a book or commissioned research report (36/40=90%). In case the study was not a part of wider research project, the most likely type of publication is an article (53/65=82%).

What does our study reveal about the level of seniority of the authors involved (measured by having received a PhD) and their disciplinary background (measured by having a law degree)? In 4% it could not be ascertained based on the study itself whether the author(s) had a PhD. However, in 74% it was apparent from the study itself that at least one author had a PhD, while in 22% of the studies no PhD-qualified researcher was involved. However, out of those 22%, over one third (n=8) undertook the research as a PhD researcher at a Dutch university. It thus appears that this type of legal research is typically carried out by researchers having or completing a PhD dissertation.

Regarding the disciplinary background of the authors, we coded whether they had a law degree (LL.M or meester in de rechten), another degree in social science or humanities, or a mix of both legal and non-legal degrees. 82 studies (78%) involved at least one author with a law degree, while 16 (15%) involved a mix of both lawyers and non-lawyers. Only two studies (2%) involved no author with a legal background. In five studies (5%) we could not discern from the study itself what the disciplinary background of the author(s) was. It follows that systematic case law analysis is a type of research that is carried out in the Netherlands mainly by researchers trained in law. Analysis by only non-lawyers is seldom the case, while a mix of disciplinary backgrounds is infrequent. Combined with the general conclusion that systematic case law analysis is on the rise in the Netherlands, Dutch legal researchers are increasingly engaging in this type of research and its empirical methods. Clearly, they do not leave this type of research to other disciplines, thus heeding Hall and Wright’s (2008, 64) call to get to grips with systematic content analysis as it “plays to the strengths of legal scholars”.

However, the fact that an author having a different disciplinary background is involved is not an assurance for a clear methodological account of the research undertaken. Out of the 18 studies in which authors having a social science background were involved, just eight of these (44%) we would qualify as being elaborate in the ways in which they account for the collection, selection and analysis of the data (see in detail Section 4.3).

It is interesting to note that some authors with legal training consider their systematic case law analysis as clearly empirical, while others see this approach as part of the traditional toolkit of doctrinal legal scholars. In one specific case, the authors do not view their analysis of published cases as empirical, whereas they do consider as empirical exactly the same analysis of cases that are not published. Apparently, these authors perceive the use of public and non-public data as a compelling argument to distinguish between doctrinal and empirical legal research respectively. These examples may serve to demonstrate that there is no consensus amongst Dutch academics as to whether systematic case law analysis is doctrinal or empirical legal research. However, as noted (Section 2.4), this debate is unlikely to get us any further. The two types of research are different in approach and scope, and show only a partial overlap. It is the research design and methodological accountability that links systematic case law analysis to the much-larger landscape of empirical legal research (Verbruggen 2021b, 15). It is that link we seek to explore in this article.

If we consider the scope of the analyses undertaken in our sample of studies, we observe great variance in terms of the number of legal decisions and opinions assessed, the dispute resolution bodies concerned and their level of instance (first instance, appeal and last resort), as well as the fields of law involved. The smallest number of judicial decisions and opinions analyzed in our dataset is 14, while the highest number is 4,190, the average being approximately 400 cases. We did not find any studies meeting our selection criteria that analyzed all possible entries in the digital database (see e.g. Dyevre 2021b and Medvedeva, Vols and Wieling 2020). In other words, in all studies some degree of selection (e.g. legal rule, field of law, period, court instance, et cetera) was used in the systematic case law analysis.

Court decisions are the principal source of analysis. 93% of the studies concern judicial decisions and opinions of advisors to the court (e.g. Advocates General). 5% relate to disciplinary bodies for regulated professions (like medical health care). The remaining 2% (n=2) are made up of a study looking at alternative dispute resolution institutions for consumer protection and a study combining legal opinions of two dispute resolution bodies.

Hall and Wright (2008, 66) suggest that: “Content analysis (…) works best when the judicial opinions in a collection hold essentially equal value, such as where patterns across cases matter more than a deeply reflective understanding of a single pivotal case”. With this advice they draw attention to the differences between systematic case law analysis and doctrinal legal research, where the latter has conventionally focused on one case (n=1) or a small-sized group of exceptional or weighty cases. Interestingly, most of the studies in our sample do not follow Hall and Wright's advice. The bulk (86%) analyze all possible instances of judicial decision-making (first instance, appeal and last instance—i.e. cassation in civil, criminal and tax law cases, or appeal in administrative law cases). Just some 20% (n=20) focus on first instance cases only, while 7% (n=7) deal with last instance rulings per se.6 Several authors have suggested that systematic case law analysis is an apt approach to see whether and to what extent ‘lower’ courts follow the case law of last instance courts (Peeraer and Van Gestel 2021, 195; Verbruggen 2021b, 9). This aim of exposing new trends or patterns is indeed a prevalent objective of analysis (see below).

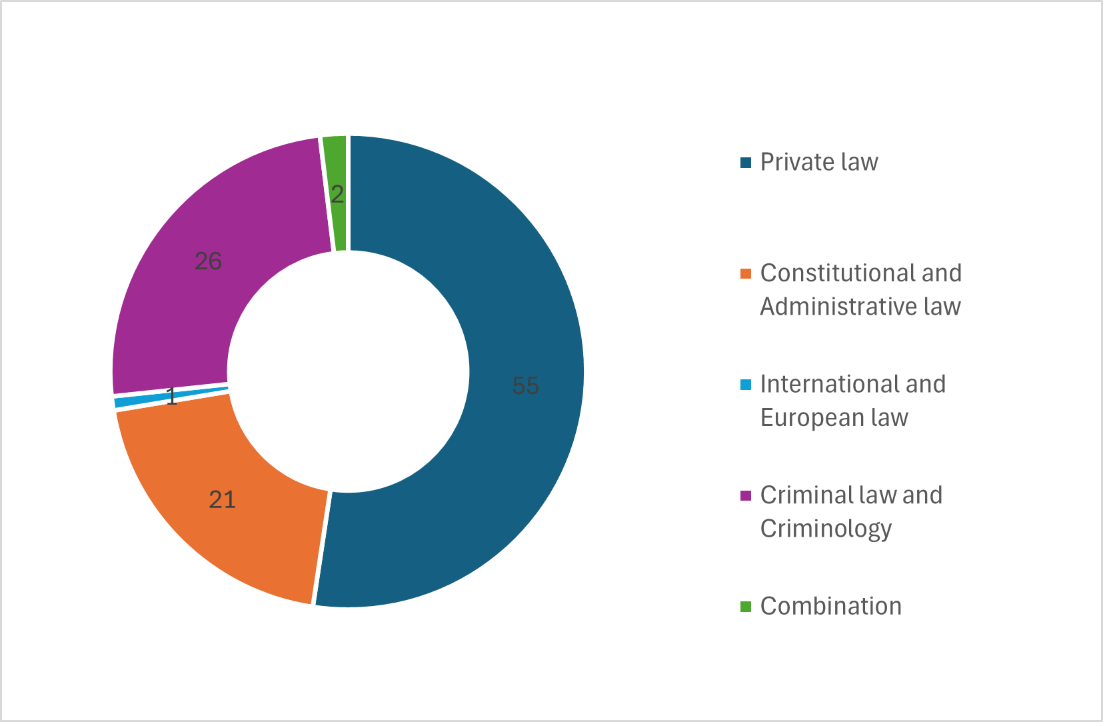

In which fields of law is systematic case law analysis deployed? Using the classification of the Dutch Research Council (NWO)7 for fields of legal research, Figure 4 shows the distribution of the studies in our sample across these fields.

Figure 4. Fields of law.

We see that in our sample private law scholars have engaged more frequently in systematic analysis of case law (54/105=51%) than scholars in other legal domains. Just two studies concerned International and European Law, one of which in combination with criminal law. That study was the only study to assess the case law of an international court, namely the Court of Justice of the European Union. This study also happens to be the study with the smallest number of cases studied (n=14) in our dataset. The underrepresentation of international and European law in our sample can, in part, be explained by a selection bias. Indeed, our focus is on academic studies published in Dutch. Surely, innovative research with this particular focus is happening in the Netherlands, in particular as part of PhD research (e.g. Brook 2022b; Medvedeva 2022; and Mol 2022). However, this research is simply not published in the Dutch language and therefore falls outside the scope of our analysis.

Another noteworthy finding is that only one study in our sample involved comparative legal analysis. This type of analysis introduces its own challenges for organizing and conducting a systematic case law analysis (e.g. data access quality and representativeness, language proficiency of coders, development of coding schemes, inter-coder reliability testing, et cetera). While there are scholars who pioneer this terrain (see e.g. Badawi and Dari-Mattiacci 2019; D’Andrea et al. 2021; De Witte et al. 2024), scholars in the Netherlands have yet to venture there.

Finally, what are the research objectives that the authors of the studies in our sample pursue with their systematic analyses? Based on our review of the literature regarding the methodology of systematic case law analysis (Section 2.2), we identified six different research objectives. We added a seventh code on this topic to our coding scheme to identify ‘other’ possible aims the authors might have and to see whether any new objectives would emerge (inductively) from the data. To code the purpose(s) of analyses we agreed to remain close to the text of the studies coded, being careful to not to read too much into the study. We thus coded what the authors themselves expressly considered to be the goal of the study. Figure 5 shows the incidence of these objectives in the studies in our sample. To be clear, one study can have more than one research objective.

Figure 5. Research objectives.

We see that finding trends and patterns in the case law studied is by far the most-often referred to objective that authors of the studies under review state. This means that 94% of the studies (99/105) are concerned, in one way or another, with identifying fact or elements that are important to case outcomes (Hall and Wright 2008, 87), that may account for variations among cases (Brook 2022a, 107; Levine 2006, 286) or that identify and map developments and regularities in the reasoning or usage of concepts by courts (Verbruggen 2021b, 9). Summarizing data to provide insights in the incidence of variables in case law (as expressed in quantitative measures such as the mean, median, mode, range and standard deviation) is also regularly pursued (46/105=44%). If the study sets this aim, very frequently the goal of finding trends (41/46=89%) is pursued too. Legal scholars in the Netherlands do not seem to be concerned much with amassing data (4/105), causal inferences (2) and jurimetrics (1). For amassing data, this may be explained by the absence of a tradition in Dutch legal scholarship to rely and build on databases constructed by other researchers. The authors that did consider this a goal of their analysis, have all done so in relation to the objective of identifying trends. For both drawing causal inferences and jurimetrics it can be said these goals show a lesser fit with classical doctrinal legal analysis and legal reasoning, in which the weighing of the factual circumstances of the case at hand plays a decisive role in understanding the outcome of cases and the concepts used (McCrudden 2006, 634).

Some 10% of the studies (11/105) expressly seek to falsify (empirical) claims made by scholars, courts or policy makers, most often in combination with the goal to find trends and patterns (9/11=82%). The category of ‘other’ objectives reveals a wider variety of goals pursued by the authors, ranging from exploring and evaluating judicial opinions, to visualizing relations between judicial opinions (with network analysis) and the training of an algorithm intended to produce reliable outcomes as to legal classifications. An objective that appeared more regularly in this residual category is categorizing judicial decisions and opinions in case types (e.g. elements litigated, concepts used, remedies sought, et cetera). Arguably, this aim closely matches the objective of summarizing, since in both cases the intention is to restructure and make sense of the vast textual data analyzed.

What do the authors tell their readership about how they have collected and selected the legal decisions and opinions that are part of their systematic analysis? As Hall and Wright (2008, 66) note: “Content analysis requires the researcher to explain the selection of cases and themes in enough objective detail to allow others to replicate the steps. This method’s persuasiveness depends on the community’s ability to reproduce the findings rather than the author's rhetorical power to proclaim them.” The collection and selection of data is, as in any other academic study, guided by the research question(s) posed by the authors. It is reassuring to observe that some 90% of the studies in our sample (93/105) included an explicit research question, while two studies (2%) used specific hypotheses to determine the focus of their systematic case law analysis.

When assessing the details the studies in our sample provide regarding data collection and selection, we first address where these studies retrieve the case law from. Over 60% (65/105) of the studies rely solely on public databases to collect and select case law. The central national database called ‘rechtspraak.nl’ is by far the most frequently used public database (59/65), even though it includes only a minor part of the case law produced by the Dutch courts.8 Any analysis involving case law published through rechtspraak.nl involves a selection bias, which the studies in our sample frequently acknowledge and expressly consider as a limitation of the results yielded. 9% (9/105) of the studies specifically try to resolve this bias by ensuring access to the internal electronic archive of the Dutch judiciary (Porta Iuris)—in which all decisions and opinions are collected—or by collaborating with court registries or law firms. More frequently—namely in 20% (21/105) of the studies—authors seek to supplement their use of rechtpraak.nl with subscription-based electronic databased (such as Kluwer navigator, Legallintelligence, rechtsorde.nl) or legal journals.9 A small number of studies (n=3) seek to triangulate the research findings by using alternative public sources (media, annual reports) or by deploying other (empirical) methods, including interviewing judges. Overall, rechtspraak.nl is used in some 80% (83/105) of the studies in our sample. Only three studies use an entirely private electronic database to collect the case law. In six studies, there is no express reference to sources used for data collection. However, it is most likely that rechtspraak.nl was relied on in these studies.

Next, it is important to consider whether the studies in our sample define the population of case law analyzed (i.e. all cases relevant to answer the research question), the criteria for selecting cases, and the search terms and sampling methods used. The studies in our sample appear to account rather well for their data collection and selection. In 95% of the studies, authors describe in some detail the population of case law, making clear which judicial decisions and opinions are relevant to answer their research questions. The same applies to selection criteria: it is apparent in most studies based on which criteria the authors selected cases. The period over which cases are assessed can be a selection criterion, but not necessarily. Nevertheless, in some 90% of the studies the authors specify the period used for selection purposes. Less apparent was the description of search terms. In over 30% of the studies, the authors do not specify the search terms used to retrieve the cases from the database. Whereas some studies are concerned with all cases in the database, these studies cannot account for all studies that did not state the research terms used. Presumably, given that the predominant database used (rechtspraak.nl) is a public database, authors pay less attention to accounting for the search terms than being clear about the population or selection criteria. The implicit assumption here is that others can easily replicate the study based on the description of the population and the selection criteria used.

Sampling turns out to be a selection technique that is rarely used in our sample of studies (7/105=7%). This finding can be explained by the urge for completeness in doctrinal legal scholarship. If it turns out the number of cases to be studied is beyond the research time and capacity of the scholars involved, an alternative strategy to reduce the work is to tweak the research question or the case population, for example by focusing on a more limited time period or on appellate or last instance courts only. If sampling is employed, however, the studies are generally clear in the method of sampling used.

A striking finding of our analysis is that only one third of the studies in our sample (35/105) provide an overview of the case that had been selected for analysis. Such an overview should enable the reader to locate the case law independently, for example by listing the case numbers or ECLI numbers. Providing such an overview (e.g. in an appendix, in footnotes, or in a separate database via the university repository) may appear trivial to the doctrinal legal scholar. After all, case law is a public good and frequently the databases or journals from which it is collected are open to scholars. If colleagues want to validate the analysis and challenge its conclusions, they can readily do so. However, providing a full overview of the judicial decisions and opinions analyzed is key to enabling others to replicate systematic case law analyses. The sample size of the studies (in our case study an average of 400 cases) combined with the research objectives of the studies, require researchers to give sufficient details about case selection (Hall and Wright 2008, 66). If this overview is missing, it is nearly impossible to understand which cases have been relied upon.10

The studies in our sample are less transparent about how the coding and analysis have been conducted. Good coding practice requires researchers to employ a coding scheme (or codebook) in which the working categories and their instructions for applying the categories are clearly set out. According to Hall and Wright (2008, 109) “this is necessary not only if someone other than the researcher, such as student assistants, performs the coding; it is also necessary even if authors do their own coding because the scientific standard of replicability requires a written record of how categories were defined and applied”. About half of the studies we reviewed use a coding scheme (57/105=54%). This percentage is slightly lower than what Hall and Wright (2008, 109) found, namely 60%. Worryingly, the reader is frequently left in the dark about the content of the coding scheme. In less than half of the studies in which such a scheme was used (27/57=47%), the reader could review its contents (e.g. as an appendix, via a website link, or the author(s) indicate that the coding scheme is available upon request).

What is more, most studies do not have a clear description of how the coding scheme was created and how the coding was performed. Only 10 studies clarify whether the coding scheme was created inductively (n=5), deductively (n=4) or through a combination of both (n=1). Often, the study does implicitly suggest which theoretical legal framework underlies the coding, but it is not explained how this framework contributed to the drafting of the coding scheme. In just 30% of the studies (32/105), it is clear how many people performed the coding (ranging from 1 to 6 coders). In the remainder of the studies, we could not confidently determine how many researchers were involved in the coding. Surprisingly, in 7 studies we could establish the number of coders, but the study did not mention any use of a coding scheme. Especially in cases where coding is performed by several researchers, it is essential to create a coding scheme, define code descriptions and agree on coding rules to ensure that the researchers involved perform the coding in the most similar way. Coding reliability was measured in only 15 studies (14%), of which just six studies explained the method used to do so (e.g. Cohen’s Kappa).

An important difference between our meta-study and of those by Hall and Wright (2008) and Vols and Jacobs (2017) is that we do not focus only on quantitative studies, but also include qualitative ones. In quantitative studies, the data collected and analyzed is numerical, and the variables are expressed in numbers. In qualitative studies, however, the data is textual in nature and variables are expressed in words (Van de Bos 2021, 19). However, quantitative and qualitative analysis approaches are not necessarily opposed when it comes to their methodological foundations. For example, both types of analysis are to be conducted systematically to formulate a clear and reproducible answer to the research question.

For the studies in our sample, we coded whether the data collected and analyzed in the studies was presented in quantitative or qualitative terms. The data that was collected and analyzed was presented quantitatively in 32% of the studies (34/105) and qualitatively in 21% (22/105). The remaining 49 studies (47%) involved a combination of both. Quantitative analyses focus predominantly on easily observable characteristics in case law, such as procedural features (from attorney representation to the number of judges hearing a case) or case outcome (amount of compensation awarded or length of criminal conviction). According to Hall and Wright (2008, 87), this is a limitation of this form of analysis:

The coding of case content does not fully capture the strength of a particular judge’s rhetoric, the level of generality used to describe the issue, and other subtle clues about the precedential value of the opinion. To some extent, the method trades depth for breadth.

Qualitative analysis of case law allows for more in-depth analysis where the complexity of a judicial decision can be considered. They may also strengthen the explanation and theoretical embedding of the findings of a quantitative analysis. In this view, it is positive to observe that in about half of the studies we reviewed quantitative and qualitative analyses are combined. For the studies in our sample, we also coded which (statistical) method was used to analyze the case law, closely following the exact words of the authors here. We looked at how the authors described and classified the method of analysis, rather than the method actually used. In 70% of the studies (74) no method is mentioned whatsoever. In the remaining 31 studies a method is mentioned, of which some 50% (16/31) it concerned a quantitative (statistical) method. The rest of these studies concerned a form of systematic content analysis (13/31) or network analysis (2/31). The statistical methods involved, for example, counts, simple statistical calculations (such as mean, median, mode) and more advanced statistical analysis techniques (such as chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test and different sorts of regression analysis). Systematic content analysis is a research method frequently used in the social sciences and especially in communication studies (Bauer 2000; Miles; Huberman and Saldaña 2014; Wester 2006). This qualitative research method is used to analyze and categorize texts or other research objects (such as images or sound recordings) in a structured and replicable way (Krippendorff 2013, 24). The use of network analysis is used to map references between judicial decisions (Kuppevelt, Van Dijck and Schaper 2020; Tjong Tjin Tai 2021, 174).

In 22% of the studies in our sample (23/105) authors mention the software used for coding and analysis. A wide variety of programs and applications are mentioned, including Atlas.ti, MaxQda, MS Excel, Nvivo and Spss. In two studies, the (network) analysis was carried out using software technology developed by the authors themselves. The technology consists of a tool to collect data and calculate network statistics, and a JavaScript application to visualize networks of statements. Only 3% of the studies in our sample used data science technology to analyse the data.

In about 60% of the studies reviewed (64/105), the limitations of the research method are explicitly reflected upon. In most cases, this concerned the observation that not all relevant case law was available in the digital database that was used (see Section 4.2 on this subject). Other limitations that have been mentioned include, the observation that the analysis focused only on certain types of cases and is not representative of other types of cases, the fact that factors that played a role in judicial decision making but are not written down were not taken into account, and that there may be relevant case law that falls outside the search terms.

Finally, in the vast majority of the studies in our sample (82/105=78%), no reference is made to methodological literature. Of the 23 studies that do, 8 refer to one source only. The remaining 15 studies do refer more extensively to methodological literature. There are many differences in the type of literature referred to. In some cases, reference is made to methodological literature specifically aimed at conducting systematic case law analysis, such as the publications we discussed in Section 2. In other cases, reference is made to more general literature on ELS (e.g. Epstein and Martin 2014; Lawless, Robbennolt and Ulen 2016) or social science methodological literature (e.g. Miles, Huberman and Saldaña 2014). Worrisome is that some studies appear to refer to methodological literatures to show that they are versed in the methodological underpinnings of systematic case law analysis, yet remain unclear as to how they have deployed these underpinnings in their analysis. No doubt that paying lip service to methodological guidelines is a dubious academic practice. Nevertheless, our findings are consistent with the observations of Vols and Jacobs (2017, 99: “interestingly, almost all publications do not refer to methodological literature”) and Hall and Wright (2008,74 “it is striking how often legal researchers employ this method without citing to any methodology literature, or only citing to examples from legal literature”).

In this study, we sought to outline the current state-of-the-art of systematic case law analysis in the Netherlands. We have conducted a systematic literature review to assess the content and methodological approach of 105 Dutch academic studies which involved a systematic case law analysis. What did we learn about the ways in which researchers in the Netherlands provide methodological accountability for this particular type of legal research? Our analysis shows that some components are clearly and comprehensively justified in many studies. For example, most studies pose a research question, define the research population, and make explicit the search terms and other selection criteria. Most studies also clearly state the purpose of the analysis. On the basis of the previous literature, we identified six research objectives that scholars seek to attain through systematic case law analysis. We found that finding trends and patterns in the case law is by far the most-often referred to objective in the studies in our sample. When setting up a research design, it is recommended to think carefully about the purpose of the systematic case law analysis to be conducted. Other objectives such as myth busting, drawing causal inferences and amassing data are virtually non-existent in the studies we analyzed. However, systematic case law analyses pursuing these objectives could make a valuable contribution to the scientific debate.

Our analysis also shows that in other areas there is room to improve methodological accountability. Many of the studies we reviewed do not provide an overview of the case law that has been coded and analyzed (e.g. in an appendix or database). This is important for the replicability of the study and can easily be arranged through university repositories or central databases for academic research (e.g. NARCIS in the Netherlands). In addition, almost half of the studies do not use a coding scheme (or at least the publication does not say so). For those studies that do use such a scheme, it is often not clear how the coding scheme was developed and whether a theoretical legal framework was used. It is also frequently not clear how the various categories are defined and how they should be applied. Only a limited number of studies deploy inter-coder reliability tests. There are clear gains to be made here. Finally, it is important to provide an account of the method of analysis used and what software or data science techniques were used to analyze the data. Again, we do not see a clear practice of this across the studies we have reviewed.

An explanation of these findings appears to be the lack of a clear and explicit tradition of quality requirements for legal (empirical) studies. As Van Gestel and others have pointed out, harmonized indicators for quality assessment of academic legal research appearing in articles and PhD dissertations are absent in the Netherlands (Van Gestel and Snel 2019, 69–73) and, more broadly, in Europe (Van Gestel and Lienhard 2019, 434–444). Editorial boards of academic journals do not make explicit or clear what level of methodological rigour and transparency is required as a quality standard for publication. Moreover, the word limits such journals employ (usually between 3,500 and 6,500 words in the Netherlands) leave little space for a full account of the methodological choices underpinning a systematic case law analysis. Nonetheless, we consider that both editorial boards and PhD dissertation committees should develop policies on what they require in terms of methodological accountability from scholars who engage in an systematic case law analysis, in particular in relation to providing an overview of the case law analyzed, the coding scheme, reliability tests and the software used for analysis. These questions will gain increasing prominence given the potential for the application of AI-based and other data science techniques in systematic case law analysis in the near future.

Related to this point is another striking finding of our analysis, namely that the studies we reviewed make little reference to methodological literature. In many cases, the researchers themselves seem to develop a method on their own to systematically analyze case law. In the words of Hall and Wright (2008, 74): “in project after project, legal researchers reinvent this methodological wheel on their own”. In our view, researchers conducting systematic case law research should refer much more extensively to methodological literature and follow the guidance this literature offers to shape the research design of the analysis undertaken. In doing so, we suggest that referring to a single source is insufficient. Researchers should firmly familiarize themselves with the methodological literature to which they refer, explaining what the source in question brings to the specific stage(s) of the analysis. The studies we reviewed do not address different research traditions, let alone provide an account of which ones the researchers consider themselves related to. For example, Hall and Wright (2008), Schreier (2012) and Miles, Huberman and Saldaña (2014) and Krippendorf (2013) all mean something different by the method of “content analysis” and propose different strategies for collection, selection, coding and analysis. By being clearer about the methodological school of taught to which they feel related to, researchers engaging in systematic case law analysis may also contribute in more sustainable ways to the ongoing methodological debates about doing systematic case law analysis.

The authors thank Ms. Fenna van der Zanden (LLB, Tilburg Law School) for her excellent research assistance during this project.

Badawi, Adam B., and Giuseppe Dari-Mattiacci. 2019. “Reference Networks and Civil Codes.” In Law as Data: Computation, Text, and the Future of Legal Analysis, edited by Michael A. Livermore and Daniel N. Rockmore, 345–70. Santa Fe, New Mexico: The Santa Fe Institute Press.

Bauer, Martin W. 2000. “Classical Content Analysis: A Review.” In Qualitative Researching with Text, Image and Sound: A Practical Handbook, edited by Martin W. Bauer and George Gaskell, 131–51. London: SAGE Publications.

Bijleveld, Catrien C.J.H. 2020. Research methods for Empirical Legal Studies. The Hague: Boom juridisch.

Brook, Or. 2022a. “Politics of Coding: On Systematic Content Analysis of Legal Text.” In Behind the Method: The Politics of European Legal Research, edited by Marija Bartl and Jessica C. Lawrence, 109–23. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Brook, Or. 2022b. “Non-Competition Interests in EU Antitrust Law: An Empirical Study of Article 101 TFEU.” PhD diss., University of Amsterdam, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Burton, Mandy. 2017. “Doing empirical research. Exploring the decision-making of magistrates and juries.” In Research Methods in Law, edited by Dawn Watkins, 66–85. London: Routledge.

Cane, Peter, and Herbert M. Kritzer. 2010. The Oxford Handbook of Empirical Legal Research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chen, Daniel L. 2019. “Judicial analytics and the great transformation of American Law.” Artificial Intelligence and Law 27 (March): 15–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10506-018-9237-x.

D’Andrea, Sabrina, Nikita Divissenko, Maria Fanou, Anna Krisztián, Jaka Kukavica, Nastazja Potocka-Sionek, and Mathias Siems. 2021. “Asymmetric Cross-Citations in Private Law: An Empirical Study of 28 Supreme Courts in the EU.” Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law 28 (4): 498–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/1023263X211014693.

De Witte, Folker, Anna Krisztián, Jaka Kukavica, Nastazja Potocka-Sionek, Mathias Siems, and Vasiliki Yiatrou. 2024. “Decoding Judicial Cross-Citations: How Do European Judges Engage with Foreign Case Law?” The American Journal of Comparative Law, avae021, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcl/avae021.

Dyevre, Arthur. 2021a. “The Promise and Pitfall of Automated Text-Scaling Techniques for the Analysis of Jurisprudential Change.” Artificial Intelligence and Law 29 (2): 239–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10506-020-09274-0.

Dyevre, Arthur. 2021b. “Exploring and Searching Judicial Opinions with Top2Vec.” In Methoden van rechtspraakanalyse: Tussen juridische dogmatiek en data science, edited by Paul Verbruggen, 143–61. The Hague: Boom juridisch.

Edwards, Harry T., and Michael A. Livermore. 2009. “Pitfalls of Empirical Studies that Attempt to Understand the Factors Affecting Appellate Decisionmaking.” Duke Law Journal 58 (8):1895–1989.

Epstein, Lee, and Andrew D. Martin. 2014. An introduction to empirical legal research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Epstein, Lee, and Gary King. 2002a. “The Rules of Inference.” The University of Chicago Law Review 69 (1): 1–133. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1600349.

Hall, Mark A., and Ronald F. Wright. 2008. “Systematic Content Analysis of Judicial Opinions.” California Law Review 96 (1): 63–122.

Hunter, Caroline, Judy Nixon, and Sarah Blandy. 2008. “Researching the Judiciary: Exploring the Invisible in Judicial Decision Making.” Journal of Law and Society 35 (1): 76–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6478.2008.00426.x.

Hutchinson, Terry, and Nigel Duncan. 2012. “Defining and describing what we do: Doctrinal legal research.” Deakin Law Review, 17 (1): 83-119.

Kastellec, Jonathan P. 2010. “The statistical analysis of judicial decisions and legal rules with classification trees.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 7 (2): 202–30. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/QSICEX.

Krippendorff, Klaus. 2013. Content Analysis. An introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Lawless, Robert M., Jennifer K. Robbennolt, and Thomas S. Ulen. 2016. Empirical Methods in Law. Boston: Aspen Publishing.

Levine, Kay L. 2006. “The Law is Not the Case: Incorporating Empirical Methods into the Culture of Case Analysis.” University of Florida Journal of Law and Public Policy 17 (2): 283–302.

Livermore, Michael A., and Daniel N. Rockmore. 2019. Law as Data: Computation, Text, and the Future of Legal Analysis. Santa Fe, New Mexico: The Santa Fe Institute Press.

McCrudden, Christopher. 2006. “Legal Research and the Social Sciences.” Law Quarterly Review 122: 632–650.

Medvedeva, Masha, Michel Vols, and Martijn Wieling. 2020. “Using Machine Learning to Predict Decisions of the European Court of Human Rights.” Artificial Intelligence and Law 28 (2): 237–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10506-019-09255-y.

Medvedeva, Masha. 2022. “Identification, Categorisation and Forecasting of Court Decisions.” PhD diss., Rijksuniversiteit Groningen.

Miles, Matthew B., A. Michael Huberman, and Johnny Saldaña. 2014. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Mol, Charlotte. 2022. “The Child’s Right to Participate in Family Law Proceedings: Represented, Heard or Silenced?” PhD diss., Utrecht University, Cambridge: Intersentia.

Nieuwstadt, Huub, and Esther van Schagen. 2007. “De juristen moeten de vragen stellen.” Ars Aequi 56 (11): 920–25.

Oldfather, Chad M., Joseph P. Bockhorst, and Brian P. Dimmer. 2012. “Triangulating Judicial Responsiveness: Automated Content Analysis, Judicial Opinions, and the Methodology of Legal Scholarship.” Florida Law Review 64 (5): 1189–1242.

Peeraer, Frederik, and Rob A.J. van Gestel. 2021. “Systematische jurisprudentieanalyse als uitdaging voor onderwijs en onderzoek.” In Methoden van systematische rechtspraakanalyse: Tussen dogmatiek en data science, edited by Paul Verbruggen, 185–212. The Hague: Boom juridisch.

Raad voor de rechtspraak. 2023. “Jaarverslag 2023.” https://www.rechtspraak.nl/SiteCollectionDocuments/Jaarverslag%20Rechtspraak%202023.pdf

Rantanen, Jason. 2016. “Empirical analyses of judicial opinions: methodology, metrics and the federal circuit.” Connecticut Law Review 49 (1): 229–91.

Salehijam, Maryam. 2018. “The Value of Systematic Content Analysis in Legal Research.” Tilburg Law Review 23 (1): 34–42. https://doi.org/10.5334/tilr.5.

Schebesta, Hanna. 2018. “Content Analysis Software in Legal Research: A Proof of Concept Using ATLAS.ti.” Tilburg Law Review 23 (1): 23–33. https://doi.org/10.5334/tilr.1.

Schepers, Iris, Masha Medvedeva, Michelle Bruijn, Martijn Wieling, and Michel Vols. 2023. “Predicting citations in Dutch case law with natural language processing.” Artificial Intelligence and Law (online pre-publication) https://doi.org/10.1007/s10506-023-09368-5.

Schreier, Margrit. 2012. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice. London: SAGE Publications.

Smit, Monika, Bert Marseille, Arno Akkermans, Marijke Malsch, and Catrien Bijleveld. 2020. “25 jaar empirisch-juridisch onderzoek in Nederland. Een inleiding tot de Encyclopedie ELS.” In Nederlandse Encyclopedie Empirical Legal Studies: Encyclopedie van 25 jaar empirisch juridisch onderzoek in Nederland, edited by Catrien Bijleveld, Arno Akkermans, Marijke Malsch, Bert Marseille, and Monika Smit, 11–20. The Hague: Boom Juridische uitgevers.

Smits, Jan M. 2009. Omstreden rechtswetenschap: Over aard, methode en organisatie van de juridische discipline. The Hague: Boom Juridische uitgevers.

Smits, Jan M. 2019. “What is Legal Doctrine? On the aims and methods of legal-dogmatic research” In Rethinking Legal Scholarship. A transatlantic dialogue, edited by Rob van Gestel, Hans-W Micklitz and Edward L. Rubin, 207–28. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Snel, Marnix, and Janaína De Moraes. 2018. Doing a Systematic Literature Review in Legal Scholarship. The Hague: Eleven International Publishing.

Stolker, Carel J.J.M. 2003. ”’Ja, geléérd zijn jullie wel!’ Over de status van de rechtswetenschap.” Nederlands Juristenblad (15): 766–78.

Stolker, Carel C.J.J.M. 2014. Rethinking the Law School. Education, Research, Outreach and Governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tijssen, Hervé E.B. 2009. “De juridische dissertatie onder de loep: De verantwoording van methodologische keuzes in juridische dissertaties.” PhD diss., Tilburg University, The Hague: Boom Juridische uitgevers.

Tjong Tjin Tai, Eric. 2021. “Methodologische aspecten van een data pipeline voor rechtspraakanalyse.” In Methoden van systematische rechtspraakanalyse: Tussen dogmatiek en data science, edited by Paul Verbruggen, 125–41. The Hague: Boom juridisch.

Van Boom, Willem H., Pieter Desmet, and Peter Mascini. 2018. “Empirical legal research: Charting the terrain.” In Empirical Legal Research in Action. Reflections on Methods and their Applications, edited by Willem H. van Boom, Pieter Desmet, and Peter Mascini, 1–22. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Van den Bos, Kees. 2021. Inleiding empirische rechtswetenschap. The Hague: Boom juridisch.