Article History Submitted 7 February 2025. Accepted 9 May 2025. Keywords Adult Guardianship, Older Adults, CRPD, Court File Study, the Netherlands |

Abstract This study examines the problem constellations of older adults placed under guardianship in the Netherlands, drawing on data from a large-scale analysis of full, financial and personal guardianship court files. Using thematic analysis and multiple correspondence analysis, we investigated whether ‘subgroups’ of older adults with similar characteristics can be identified within the population of older adults under guardianship, and whether certain types of adult guardianship measures are more frequently applied within these subgroups. We distinguished four subgroups of older adults with distinctive profiles. These profiles were then matched with the different types of guardianship measures, offering valuable insights into the population of older adults under guardianship and their position within the Dutch legal framework of support and protection. Our findings suggest that tailored and less restrictive alternatives may be feasible for some older adults, while for others, adult guardianship measures remain the most appropriate safeguard for their financial and personal interests. |

|---|

The rapidly growing number of older adults worldwide intensifies the need to address the challenges associated with population ageing (Officer, et al. 2020, World Health Organization 2023). As people live to a more advanced age, the risk of developing health problems increases, potentially affecting cognitive functioning. Impaired cognitive abilities among older adults are often caused by neurological conditions, such as dementia, stroke and Parkinson's disease, but could also result from pre-existing intellectual disabilities or psychiatric disorders (Kim and Song 2018, Tompkins, Connors and Robinson 2024). Older adults with impaired cognitive abilities can experience difficulties with decision-making, for instance in financial or healthcare matters, and may require ongoing support from others (Bangma, et al. 2021). The majority of older adults rely on informal arrangements for decision-making support, typically involving family or close relationships (McSwiggan, Meares and Porter 2016). When informal arrangements are unavailable or when conflicts arise, a legal intervention may be necessary to avoid adverse consequences such as delayed or unwanted medical treatments and financial abuse (Belbase, Sanzenbacher and Walters 2019, Catlin, et al. 2022).

A variety of legal mechanisms, including adult guardianship, exist to provide support and protection for older adults with impaired decision-making abilities. Adult guardianship is commonly defined as a state-ordered measure aimed at protecting the interests of the person under guardianship by appointing a guardian to manage their financial and/or personal affairs (Nwakasi and Roberts 2022). The application of most guardianship measures involves a limitation of the adult’s legal capacity. Legal capacity refers to the ability of persons to make legal decisions and have those decisions upheld by the law, for instance by signing a lease agreement or consenting to medical treatment. The right to legal capacity is guaranteed under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD).5 According to Article 12 of the CRPD, State Parties must recognize that persons with disabilities enjoy legal capacity on an equal basis with others in all aspects of life and take appropriate action to provide access to the support they may require in exercising their legal capacity. Furthermore, State Parties must ensure that all measures that relate to the exercise of legal capacity are effectively safeguarded, respect the person’s rights, will, and preferences, and are tailored to their specific circumstances. There is increasing pressure on State Parties to replace restrictive protection measures, such as adult guardianship, with support measures that respect the adult’s right to legal capacity, as well as other human rights (Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2014).

Adult guardianship measures of various kinds are prominently present in many jurisdictions today, including those jurisdictions that have ratified the CRPD. The significant implications of adult guardianship for the right to legal capacity, however, raise contentious questions about whether and under what circumstances it should be considered an appropriate intervention (Näkki, et al. 2024). This study examines the situation of older adults placed under guardianship in the Netherlands, a State Party to the CRPD that currently has three different kinds of adult guardianship measures in place. Upon ratifying the CRPD in 2016, the Netherlands made reservations regarding the interpretation of several provisions of the Convention, including Article 12. The Netherlands interprets Article 12 in such a way that it allows for the application of adult guardianship measures, provided that such measures are limited to situations where their application is necessary and imposed as a last resort.6

A deeper understanding of the relevant facts and circumstances — or ‘problem constellations’ — of older adults who require such a last-resort guardianship measure is essential when examining the appropriateness of adult guardianship and the necessity to develop alternative support mechanisms. However, only scant empirical information is available on the population of older adults placed under guardianship in the Netherlands (Nieuwboer, et al. forthcoming). Previous empirical research concentrated primarily on the experiences of court staff, professional guardians and voluntary guardians (Bureau Bartels 2018). Recent international empirical research regarding older adults under guardianship is also mostly focused on the experiences and perspectives of professionals (e.g. court staff, medical experts and professional guardians) and family guardians (Näkki, et al. 2024, Nwakasi and Roberts 2022, Sager, et al. 2019, Uekert 2010). Given the expected growth in the number of older adults potentially subjected to adult guardianship, as well as increasing pressure to develop appropriate and tailored support measures consistent with international human rights norms, it is vital to gain a better understanding of the empirical reality of older adults under guardianship (Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2014, Nwakasi and Roberts 2022).

Using data from a large-scale analysis of adult guardianship court files, this study employs thematic analysis and multiple correspondence analysis to explore patterns within the population of older adults under guardianship in the Netherlands. By doing so, we aim to answer the following research questions: (1) To what extent can ‘subgroups’ of older adults with similar characteristics be discerned within the population of older adults under guardianship? And (2) to what extent are certain types of adult guardianship measures more frequently applied within these subgroups? By identifying potential subgroups of older adults under guardianship and analysing the types of guardianship measures most commonly applied within each subgroup, we aim to gather insights that can be used to tailor the existing guardianship measures to the specific needs of the adults involved. Additionally, the older adults within (some of) these subgroups could potentially be subjected to less restrictive support measures rather than to adult guardianship, based on their specific characteristics. These insights may therefore contribute to the improvement of support and protection of older adults placed under guardianship in the Netherlands and enrich the current body of empirical research focused on older adults under guardianship. Before discussing the methodology and findings of the study, we first briefly introduce the Dutch legal framework of support and protection of older adults.

The Dutch Civil Code (DCC) serves as the primary legal framework for the support and protection of (older) adults in the Netherlands. The legal authority to act and decide on behalf of another adult may be provided by operation of the law (ex lege measures), by a legal act of the adult him- or herself (voluntary measures) or by a court decision (adult guardianship measures).

Legal authority by operation of the law, or ex lege, refers to the ‘automatic’ authority given to individuals to represent the interests of the adult in certain matters. No legal action is required by the adult in question or the court (Blankman and Stelma-Roorda 2023). The Medical Treatment Act (which is part of the DCC) provides an ex lege authority for certain individuals to act as representatives in medical treatment decisions. Article 7:465 of the Medical Treatment Act states that the partner or a close relative of a patient (parent, child, sibling, grandparent or grandchild) can act on their behalf, if the patient is deemed ‘incapable of a reasonable valuation of their interests pertinent to the situation’ and does not have a state-ordered or a voluntarily appointed representative.

The legal authority to act as a representative can also be provided by a legal act of the adult him- or herself at a time of decision-making capacity. For instance, the adult can grant another person the authority to manage their bank account or set up a joint bank account (de Kievit 2024). Another possibility is to draft a living will (‘levenstestament’ in Dutch), a written document that allows adults to make their own provisions in advance for a future period of decision-making incapacity. Adults can include a continuing power of attorney (CPA) in their living will. A CPA can be defined as a mandate given by a capable adult to another person to act on their behalf in a future period of decision-making incapacity. Including a CPA in a living will does not affect the drafter’s legal capacity. Adults can also include advance directives (ADs) in their living will. ADs can be defined as instructions given or wishes made regarding (medical) issues that may arise in a future period of decision-making incapacity.7 In the absence of any regulatory provisions in Dutch law, the only regulation of the living will is provided by notarial practice (Stelma-Roorda 2024).

Adults who lack both a voluntarily appointed representative and (willing) partner or relative to act as an ex lege representative for medical treatment decisions may require an intervention by the court. Under the circumstances stipulated by Dutch law, the court may decide to place an adult under guardianship and appoint a guardian to act as their representative (Rovers 2023). Guardians are supervised by the court to protect the adults under guardianship, including protection against neglect and (financial) abuse.

The DCC specifies three types of adult guardianship measures: full guardianship (‘curatele’), financial guardianship (‘beschermingsbewind’), and personal guardianship (‘mentorschap’). Full guardianship covers the adult’s financial and personal interests. It results in an almost complete limitation of legal capacity, making it the most far-reaching measure available in the Netherlands (Blankman and Stelma-Roorda 2023).8 The court can order full guardianship when an adult, temporarily or continuously, does not properly take care of his or her interests or when an adult is endangering his or her own safety or the safety of others as a result of a physical or mental condition, or as a result of habitual abuse of alcohol or drugs. Adults can only be placed under full guardianship if their interests cannot be served adequately with a more appropriate and less intrusive measure (Article 1:378 DCC).

Both financial and personal guardianship are considered less intrusive measures. The court can order financial or personal guardianship when an adult is temporarily or continuously unable to properly take care of his or her interests as a result of a mental or physical condition.9 The scope of financial guardianship is limited to the financial interests of the adult involved, meaning that the adult is no longer able to independently manage the property that has been placed under the financial guardian’s custody (Article 1:438 DCC). The scope of personal guardianship is limited to personal interests of the adult involved, more specifically their care, nursing, treatment and support, unless another act or treaty states otherwise (Article 1:453 DCC). The court can order financial and personal guardianship at the same time (Blankman and Stelma-Roorda 2023).

A request for an adult guardianship measure can be submitted by the adult himself or herself, their partner or one of their blood relatives in the direct line and in the collateral line up to and including the fourth degree. Additionally, the care facility that looks after or provides guidance to the older adult, as well as the public prosecutor, may file such request (Articles 1:379, 1:432 and 1:451 DCC). The request does not require submission by a lawyer or another legal professional, though it should be submitted using an official form. Within this form, applicants are required to describe the relevant facts and circumstances demonstrating the necessity of the adult guardianship measure. They are also asked to, if available, provide a (medical) statement from an expert (Rovers 2023). The court may grant the request for adult guardianship based on the application form and supplementary expert statement(s) but will commonly order an oral hearing before making a decision (Article 800 of the Dutch Code of Civil Procedure).

For this study, we analysed full, financial and personal guardianship court files from multiple district courts in the Netherlands. The court files contain detailed information on the relevant facts and circumstances of the older adults placed under guardianship, as recorded in the application forms, expert statements and oral hearing transcripts. Given the general lack of explicit judicial reasoning in judgments concerning the institution of adult guardianship measures, we were unable to draw conclusions about the specific characteristics considered in these decisions. It was therefore not possible to, for example, explore informal classifications that influence judicial decision-making, and thus enrich existing literature on the decision-making processes of judges (Albonetti 1991, Mascini, et al. 2016, van Oorschot, Mascini and Weenink 2017, Tombs and Jagger 2006). With the collected qualitative data, we first conducted an inductive thematic analysis to identify different patterns of characteristics (themes) within the sample of guardianship cases. The acquired themes were then used in a multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) to further examine the relationships between the different characteristics of older adults under guardianship.

Four different Dutch district courts were selected for participation in the study, with the aim of ensuring a diverse representation of geographic regions and rural-urban settings.10 Each district court was asked to provide one list per type of guardianship measure of all registered court files that met the following inclusion criteria:

The guardianship measure was instituted after January 1, 2015, following the changes to guardianship laws introduced in 2014.

The adult placed under guardianship was at least 60 years old at the time the guardianship measure was instituted. In the absence of a clear consensus on the age at which one is considered ‘old’, we adopted a 60-year threshold to ensure inclusion of a broad range of older adults in our sample.

The guardianship measure was instituted based on the physical or mental condition of the older adult, as we considered this the most appropriate ground for full, financial, and personal guardianship within the context of this study.

The guardianship measure was ongoing during the data collection phase, as the research focuses on older adults placed under guardianship. Accordingly, court files in which the request for guardianship was denied were excluded from the study.

At each district court, we drew a systematic sample of 100 court files from each list of adult guardianship measures (four courts × three types of guardianship measures × 100 = 1,200 court files total).11 As none of the district courts had 100 (or more) full guardianship cases registered that met all four criteria, all registered full guardianship cases were included for each district court (n=166). Due to practical limitations, it was not possible to draw a systematic sample for personal guardianship at one of the district courts. Instead, we asked the court staff to draw a random sample of personal guardianship court files. Given our systematic sampling strategy, the sample can be expected to be roughly representative per guardianship measure for the total population of court files that met the inclusion criteria.

The research proposal of the study was positively assessed by the Ethics Committee for Legal and Criminological Research of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (CERCO) and, in accordance with Article 35 of the General Data Protection Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2016/679), a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) was carried out prior to the data collection.

Data collection took place over a 12-month period (from April 4, 2023, until March 27, 2024). Before data collection began (October 2022), a pilot study was conducted with a subset of nine randomly selected court files to design a scoring form in Microsoft Excel. This scoring form was developed by the researchers to systematically obtain the relevant information from each court file. A primary researcher (RN) and three supporting researchers (CH, MS and RSR), all of whom have a legal background, scored the paper court files. The scoring form included both quantitative and qualitative variables and captured the following categories: general court file data, institution of the adult guardianship measure, possible follow-up procedures, and judicial supervision.12

The data contain information on the gender, age and network of the adult, as well as the application form (e.g. whether an expert statement was present), court proceedings (e.g. a transcript of the oral hearing), judgments, and documents on both the functioning of the guardianship measure and appointed guardian. We employed predefined categories for the quantitative variables. For the qualitative data, we copied pseudonymised information into the scoring form. Inter-rater reliability tests showed near-perfect agreement between the primary researcher and supporting researchers for both quantitative and qualitative data.

For this study, quantitative variables from the category ‘general court file data’ (e.g. gender and age of adult involved) and both quantitative and qualitative variables from the category ‘the institution of the guardianship measure’ (e.g. the involvement of a partner and/or children and the applicant’s motivation for adult guardianship) were analysed. The data analysis consisted of two steps: a thematic analysis and multiple correspondence analysis. For the first step, qualitative information on the applicant’s motivation for adult guardianship was analysed using ATLAS.ti (v9.5.4). Researchers RN, MS and CH used inductive thematic analysis according to the phases described by Braun and Clarke: (1) familiarizing with the data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes that capture significant patterns, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes and (6) producing the report (Braun and Clarke 2006). All researchers familiarised themselves with the data and generated initial codes for the entire dataset separately. Together, the researchers reviewed the codes in order to identify and define the main and subthemes (see results, Table 2). This inductive approach emphasizes letting themes emerge from the available data, rather than being driven by predetermined theories or frameworks. The subthemes were coded into new variable categories and used for the MCA.

Multiple correspondence analysis is a multivariate statistical technique to explore and visualize relationships among categorical variables. By transforming complex and multidimensional data into a simpler, more interpretable representation, MCA can uncover underlying structures and relationships among variable categories. MCA is often used to investigate whether certain characteristics of cases cluster, in the sense that subgroups of cases with distinctive profiles can be distinguished. MCA seeks to find an optimal multidimensional structure, also referred to as ‘solution’, where cases are positioned close to the characteristics they have, and, conversely, characteristics are positioned close to the cases that have these characteristics. MCA should not be regarded as a ‘hard’ classification technique, because characteristics can be shared by different subgroups and classification is therefore generally fuzzy (Gifi 1990).

Using MCA, we explored the multivariate relationships between different characteristics of the older adults from the analysed guardianship court files (such as age, gender, health condition and prevalence of financial abuse). As higher-dimensional analyses are much more difficult to interpret, a two-dimension solution was considered the most suitable for the MCA. For the analysis, we selected five categorical variables that were directly obtained from the court files (see results, Table 1), as well as 30 categorical variables obtained from the thematic analysis (see results, Table 2).13 These variables were included in the MCA as active variables, meaning that they influence the position of the guardianship cases in the multidimensional solution and therefore define the structure. The variable ‘Guardianship Measure’ (see results, Table 1) was included as a so-called supplementary variable, meaning that this variable was included after generating the solution to provide contextual insights. The dataset used for the MCA contained no missing data.

The MCA was performed using the FactoMineR package, a package for multivariate data analysis with R software (version 4.4.1) (Lê, Josse and Husson 2008). The Factoshiny library, which gives a graphical interface to the FactoMineR package, was used to draw the plots.

The gross sample consisted of 1,578 adult guardianship court files. Of these 1,578 court files, 500 court files could not be found in the designated storage locations, 132 court files did not meet the inclusion criteria upon further review, 36 court files were already present in the sample (because they were listed for both financial and personal guardianship), and four court files did not contain any documents. These court files were excluded from the study. The remaining 906 court files were substantively examined and used for the analysis.

Table 1 shows the categorical variables obtained directly from the court files, which were used for the MCA. Most older adults were female (61.3%), between the age of 70 and 84 (60.6%), and had been placed under a combination of financial and personal guardianship (53.8%). Quite a few older adults that were placed under guardianship had a relatively small (family) network, although the collected data on partners, children and siblings were based on the application forms and might be incomplete.14

| Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of sample. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Categories | Percentage |

| Guardianship Measure | Full Guardianship Financial & Personal Guardianship Financial Guardianship Personal Guardianship |

10.8 53.8 29.2 6.2 |

| Gender | Male Female |

38.7 61.3 |

| Age Category | 60–64 65–69 70–74 75–79 80–84 85–89 90–94 95–99 |

5.0 11.0 17.7 20.6 22.3 14.2 7.1 2.1 |

| Partner | Yes No |

24.1 75.9 |

| Children | Yes No |

63.6 36.4 |

| Siblings | Yes No |

25.4 74.6 |

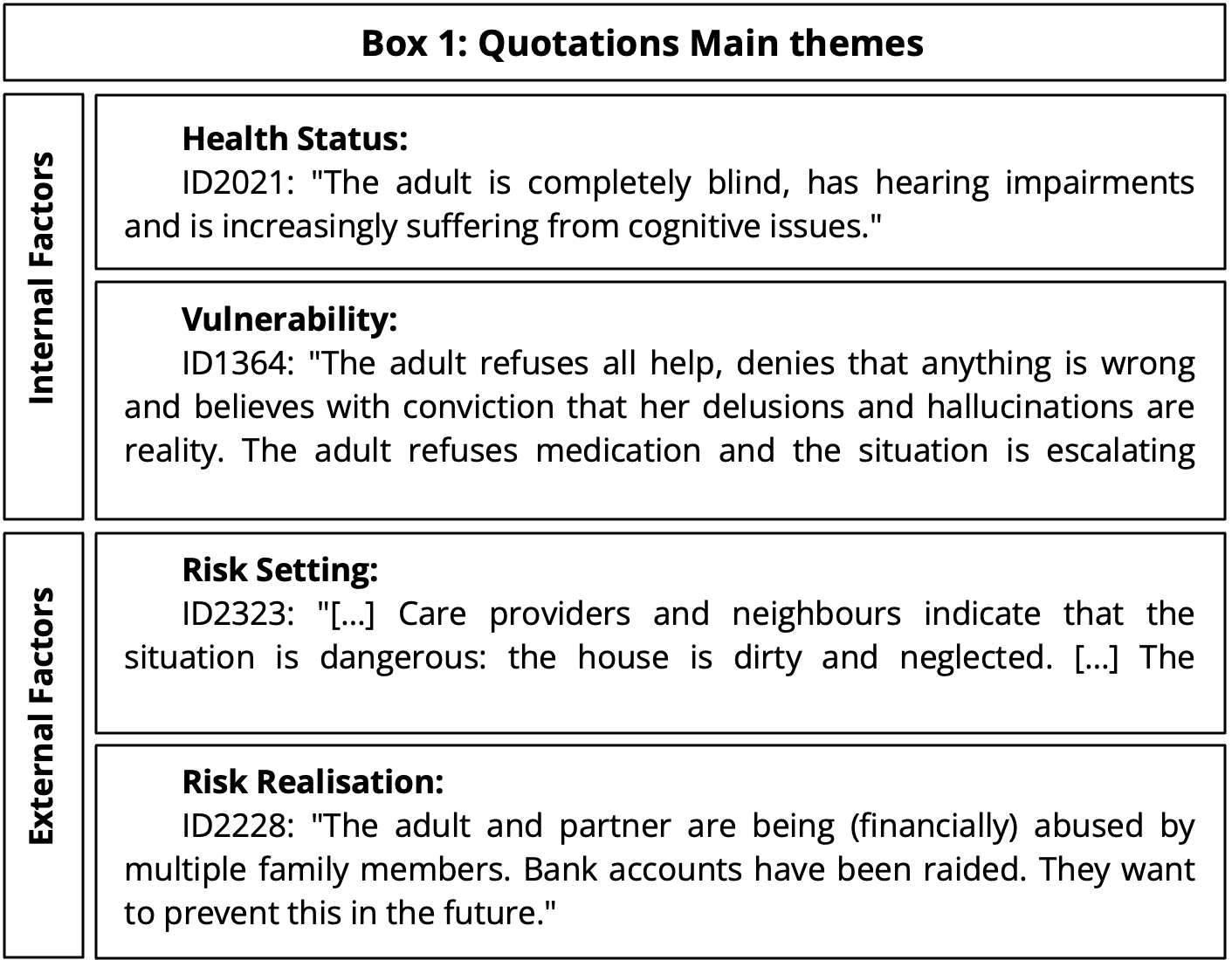

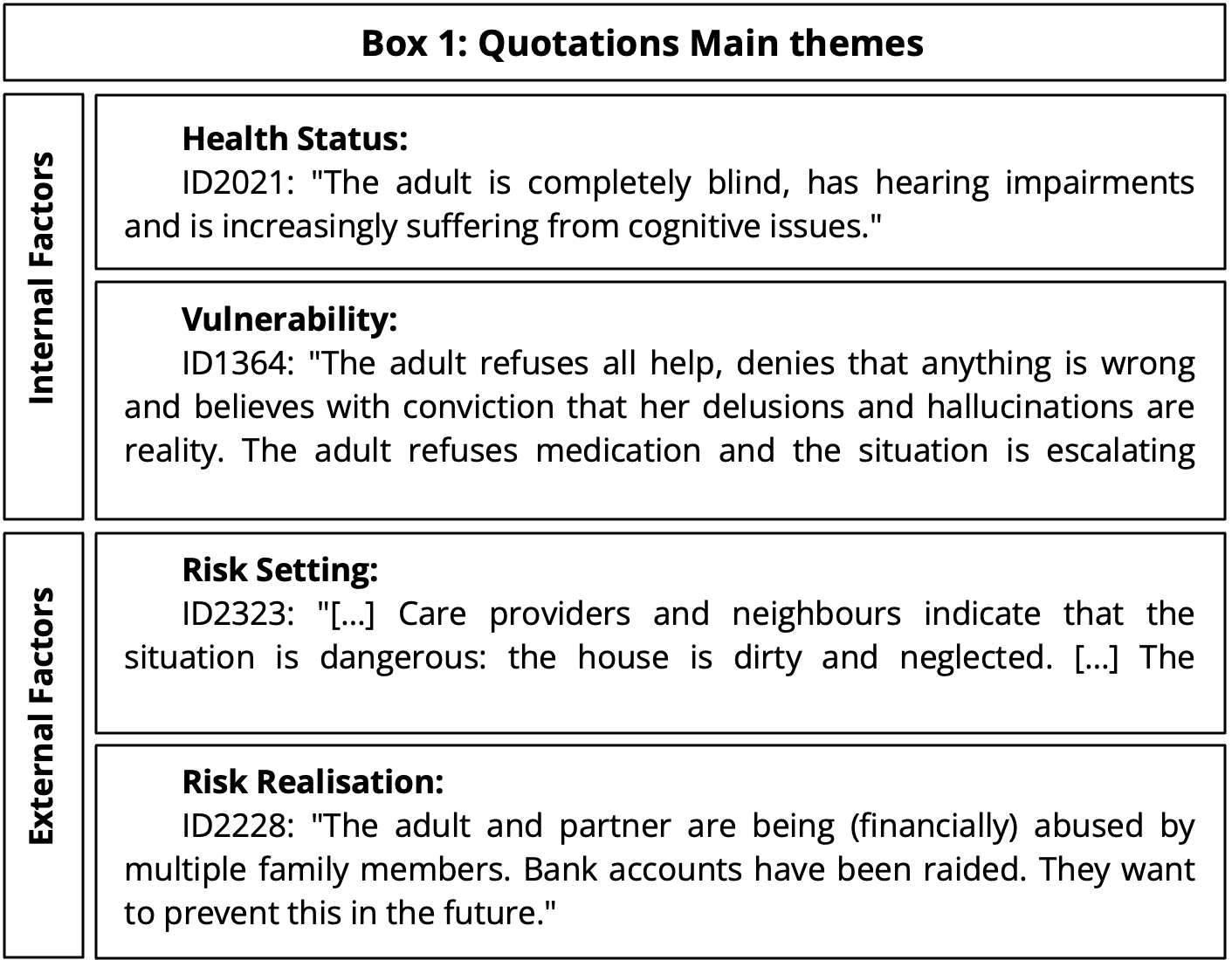

Using inductive thematic analysis for the applicant’s stated motivation for the need for guardianship, possibly supplemented with information from expert statements and/or transcripts of the oral hearing, four main themes were distinguished: ‘Health Status’, ‘Vulnerability’, ‘Risk Setting’ and ‘Risk Realisation’. The first two themes are made up of internal factors, including the health and behaviour of the older adult involved. The second two themes are made up of external factors relating to the environment of the older adult, including their network and living situation. Box 1 includes four passages from court files, each exemplifying one of the main themes.

Box 1. Court file quotations reflecting the four main themes, translated into English.

All main themes encompass various subthemes, listed in Table 2.15 These subthemes should be viewed as interrelated, given that the problem constellations of older adults placed under guardianship are often made up of a combination of different internal and external factors. In the majority of guardianship cases, we observed a combination of multiple subthemes from different main themes. We will further discuss the main themes and corresponding subthemes in the following subsections.

| Table 2. Main themes and subthemes from thematic analysis. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Main Theme | Subthemes | Percentage |

| Health Status | Combination of Conditions Dementia Intellectual Disability Other Brain Condition Other Condition Psychiatric Disorder Stroke Unknown |

6.5 54.0 6.4 5.3 1.8 7.6 5.6 12.7 |

| Vulnerability | Addiction Issues Behavioural Issues Care Avoidance Care/Support Needs Confused, Forgetful and/or Paranoid Behaviour Influenceable Lack of Knowledge/Experience Lack of Self-Reliance Limited Decision-Making Skills Limited Digital Skills Limited Language Skills Limited Understanding Finances Limited Understanding Illness Loss of Oversight Self-Negligence Stress, Anxiety and/or Panic Limited Communication Skills |

2.7 2.0 2.5 22.9 10.3 2.3 2.3 6.4 7.0 1.7 5.8 6.9 5.1 11.4 5.5 2.8 1.3 |

| Risk Setting | Admission Care Facility (CF) Concerns Financial Abuse Concerns Financial Situation Conflict within Network Loss within Network Network Overburdened No (contact with) Network Practical Problems Unsafe Living Conditions Unsafe situations Concerns Financial Abuse Living Will Concerns Living Situation Concerns Undue Influence Living Will no longer Possible Living Will not Enforceable Does not want to Burden Network |

17.9 6.0 7.0 6.2 7.0 14.7 12.5 6.3 3.0 2.5 0.7 1.1 1.1 1.3 0.3 1.0 |

| Table 2. Main themes and subthemes from thematic analysis (cont.) | ||

| Main Theme | Subthemes | Percentage |

| Risk Setting | Does not want to Inform Network Possible Eviction |

1.2 1.0 |

| Risk Realisation | Financial Abuse Problematic Debt/Squander Undue Influence Criminal Offender Crisis Admission CF Homelessness Victim of Abuse |

3.8 6.5 1.7 0.8 0.6 0.6 0.7 |

| Note: All identified subthemes that have not been used in the multiple correspondence analysis are shown in italics. | ||

The theme Health Status focuses solely on the mental or physical condition of the older adult involved. Most applicants explicitly mentioned the adult’s mental or physical condition. Some applicants mentioned a type of dementia, a specific psychiatric disorder or an intellectual disability. For example, one of the applicants stated that “The adult has advanced Alzheimer's disease.” (ID3086). Other applicants only referred to an attached (medical) statement by an expert, which provided the necessary information on the mental or physical condition of the adult. When the applicant did not provide information on the health status of the older adult on the application form and did not attach any expert statements, the mental or physical condition was labelled as ‘Unknown’.

The theme Vulnerability is related to the behaviour, mental state or to a lack of relevant skills, knowledge or experience that makes the older adult ‘vulnerable’ when making financial and/or personal decisions. The behaviour and mental state can oftentimes be linked to the older adult’s mental or physical condition. For instance, one applicant mentioned that “The adult is very confused, their short-term memory is completely gone, and the adult has been diagnosed with Korsakoff syndrome.” (ID4129). One of the subthemes of Vulnerability related to the lack of relevant skills, knowledge or experience of the adult, is labelled ‘Limited Language Skills’. This subtheme mainly occurred in guardianship cases in which the older adult did not speak Dutch or was struggling to read and write, making it difficult for them to take care of their financial and/or personal interests. Some applicants reported that the adult experienced stress, anxiety and/or panic when faced with tasks like opening mail or paying bills. When an adult is unable to handle such responsibilities, the risk of falling into debt or becoming a victim of financial abuse may increase. These (and other) risks are addressed within the main themes Risk Setting and Risk Realisation.

Subthemes within the theme Risk Setting are linked to external factors, like the adult’s network, living conditions or financial situation, which are a possible threat to the (financial) health of the older adult. Applicants often referred to either the absence or overburdening of the adult’s network as a factor expediting the need for guardianship. A number of applicants mentioned that they or other persons within the network of the older adult were concerned about possible financial mismanagement or abuse. The living conditions of the older adult were also mentioned repeatedly. Some older adults still lived independently, a few in appalling and dangerous conditions. One applicant referred to an attached statement of a social worker, in which the social worker stated that home care services refused to visit the adult due to the polluted state of their house (ID4163). Some applicants mentioned other unsafe situations, for example that one of the adults was still driving their car, even though their license had been revoked. A few applicants mentioned the existence of a living will, for example that the person who was awarded a continuing power of attorney in the living will was no longer able to perform his or her duties (labelled as ‘Living Will not Enforceable’) or concerns about possible financial abuse within the context of the living will.

The last theme, Risk Realisation, entails a small collection of subthemes where the (financial) health of the older adult or someone else was compromised. Some older adults had become a victim of financial abuse, often at the hands of a family member. Other adults ended up with a substantial amount of debt, as they were unable to manage their finances individually. For instance, one of the applicants mentioned that “The adult has rental debts and is subject to a court-ordered eviction. The adult is unable to manage their finances and pay off their debts.” (ID1242). Undue influence was also (implicitly) mentioned by some of the applicants, which can be defined as excessive persuasion that causes another person to act or refrain from acting by overcoming that person’s free will and causing inequity (Quinn, et al. 2017). We encountered some appalling cases. In one of these cases, a report from the municipality mentioned an older adult living in a small shed next to their informal caregiver’s garage, who was completely dependent on the informal caregiver for food, personal hygiene and care, and weighed only around 35 kgs (ID4082). A small number of requests for adult guardianship were submitted after the older adult had been charged with a criminal offense and was staying in prison or a penitentiary treatment facility (‘TBS’).

Figures 1–3 show the plots of the MCA, based on a two-dimension solution. Each dimension explains a certain proportion of the total variance in the dataset. The percentage of variance tells you how much of the overall structure in the data is captured by that specific dimension. The first dimension (Dim.1) accounted for 5.33% of the total variance. The second dimension (Dim.2) accounted for an additional 4.27% of the variance. In the first plot (Figure 1), the distribution of all adult guardianship cases is shown. This scatter plot illustrates that the guardianship cases are well distributed within the solution. The guardianship cases that are placed in the centre are relatively ‘average’ cases that do not have distinctive profiles. Guardianship cases that share certain distinguishing characteristics are close to each other and located further away from the centre of the solution.

Figure 1. Scatter plot of the individual guardianship cases.

The second plot (Figure 2) depicts the categories of the variables in the solution. This plot shows only the important contributors to the solution. Variable categories that have contributed less to the structure of the solution are depicted in Figure 2 as semi-transparent triangles. Most of these variable categories are located in the centre of the solution, as they are shared by many guardianship cases.

Figure 2. Contribution plot of the categories of qualitative variables.

We discerned four profiles of older adults under guardianship from the solution. Box 2 provides text fragments from court files that highlight the patterns of characteristics associated with each profile. As previously noted, MCA is not a hard classification technique and guardianship cases may therefore share characteristics of multiple profiles. Our interpretation of the solution should be regarded with this in mind. The four profiles — or the subgroups they typify — are labelled ‘Care Dependents’, ‘Isolated Influenceables’, ‘Dangerous Avoiders’ and ‘Financial Mismanagers’. The chosen labels are used for ease of writing and do not capture the full complexity of the older adults within each subgroup.

Two variable categories depicted in Figure 2 are not located within a specific profile, ‘Having a Partner’ and ‘Addiction Issues’, because these categories seem to be shared by multiple subgroups. Having a Partner appears to be a shared characteristic of Care Dependents and Financial Mismanagers, and to some extent Isolated Influenceables. Addiction Issues appears to be a shared characteristic of Isolated Influenceables and Dangerous Avoiders, and will be further discussed in subsection 4.3.5.

Box 2. Court file quotations reflecting the four subgroups, translated into English.

The first subgroup, Care Dependents, is located in the first quadrant of Figure 2, relatively close to the centre of the solution. This subgroup can be described as consisting of primarily older women (80-99) with some type of dementia, who have been admitted into a care facility due to increased care needs. Some of the adults in this subgroup had (recently) lost their partner or had a partner who was no longer able to adequately take care of them. Many adults in the Care Dependents subgroup had children who, although not always in a position to provide care and support (e.g. due to their own health limitations or because they lived abroad) continued to be involved in their support network. A number of older adults in the subgroup of Care Dependents experienced practical problems (see Appendix, Table 4, for coordinates). One of the most frequently mentioned practical problems involved the sale of the adult’s home following their admission into a care facility. In several cases, the adult's signature was required for the sale, but they were no longer able to provide it due to their cognitive condition. In the absence of a CPA to act on behalf of the adult, their children (or other family members) were ‘forced’ to apply for a guardianship measure.

The second subgroup, Isolated Influenceables, is located in the second quadrant of Figure 2, also relatively close to the central point of the solution. This subgroup mostly consists of adults with psychiatric disorders and/or dementia who are at an increased risk of financial abuse and undue influence.16 The subgroup is not characterised by a specific gender or age category. In the subgroup of Isolated Influenceables we often observed older adults without a support network or, less frequently, in conflict with their network. For example, one adult’s partner, who had previously managed all finances, passed away. The adult was unable to handle financial matters alone and involved various others to assist with withdrawing money and managing paperwork, as relatives were unable to offer support (ID3126). Additionally, some of the adults have a limited understanding of their illness, experience a loss of oversight, display confused, forgetful or paranoid behaviour, or show a lack of self-reliance. Others faced issues related to alcohol or drugs abuse. These vulnerability characteristics increase the risk of undue influence and financial abuse of the adults within this subgroup. A small number of adults within Isolated Influenceables have been harmed by undue influence and/or financial abuse (see Appendix, Table 4, for coordinates).

The third subgroup, Dangerous Avoiders, is also located in the second quadrant of Figure 2. Typical for this subgroup is that the adults live in unsafe conditions and refuse any support or care from others. Most adults in the subgroup Dangerous Avoiders live independently, often causing disturbances in their neighbourhood. Some of their homes are dirty and infested with vermin. One of the adults lived in a home without gas — which meant there was no central heating and no possibility of heating up food — for two years (ID4175). Several adults in this subgroup were malnourished or eating expired and spoiled food. Unsafe situations were created when these adults wandered around, drove a car with a revoked license or forgot to turn off their stovetop. Another common characteristic among adults in the subgroup of Dangerous Avoiders is that they reject any type of help from people within their network, home care services and social workers. The subgroup consists of both men and women of different ages and with different (mental and/or physical) conditions, and some of the adults struggle with an alcohol or drug addiction. For instance, one of the adults was described as an alcoholic who had multiple health issues, was neglecting himself and became angry when anyone tried to help him (ID1237).

The final subgroup, Financial Mismanagers, can be described as a slightly larger cluster located in the third quadrant of Figure 2. The subgroup consists of quite a number of younger men (60-74), who often had intellectual disabilities and difficulties managing their finances. In addition to intellectual disabilities, other conditions like Parkinson’s disease and brain injuries were also relatively common in this subgroup (see Appendix, Table 4, for coordinates). Furthermore, the subgroup Financial Mismanagers can be typified by a set of vulnerability characteristics, such as a lack of knowledge and/or experience, limited language skills and a limited understanding of finances. For example, some adults in this subgroup were unable to manage their bank accounts or mail independently due to intellectual disabilities. The adults in this subgroup often had no children. Some of the adults had been supported by their parents their entire life using informal arrangements, and the need for guardianship arose after the parents passed away. In some cases, the siblings of the adult tried to take on the responsibility of supporting their brother or sister but became overburdened with the task. Several adults within the subgroup of Financial Mismanagers had a partner who had an intellectual disability as well.

As mentioned in the methodology section, the variable ‘Guardianship Measure’ was treated as a supplementary variable to deepen our insight into how the different types of guardianship measures correspond to the problem constellations of each of the identified subgroups. Figure 3 shows the plot of the guardianship measures and their position in relation to the subgroups. All guardianship measures are positioned quite centrally, implying that they are not uniquely associated with specific problem constellations. Nevertheless, we do see some differences.

Figure 3. Plot of the categories of supplementary variable ‘Guardianship Measure’.

The most restrictive guardianship measure, full guardianship, is located in the second quadrant of Figure 3, within the subgroup of Isolated Influenceables. In our interpretation of the data, full guardianship is relatively common for adults with a profile that matches this subgroup and adults with a profile that matches the subgroup of Dangerous Avoiders (also located in the second quadrant). This observation appears to correspond closely with the legal criteria for full guardianship, as outlined in Article 1:378 of the Dutch Civil Code. Under this provision, full guardianship may be imposed when an adult endangers their own safety or the safety of others. The adults within the subgroup Isolated Influenceables are often endangering their own safety, and the adults within the subgroup Dangerous Avoiders are frequently endangering both their own safety and the safety of others. Additionally, full guardianship can be ordered by the court if the adult does not properly take care of his or her interests as a result of habitual abuse of alcohol or drugs. As ‘Addiction Issues’ is a shared characteristic of Isolated Influenceables and Dangerous Avoiders, the application of Full Guardianship within these subgroups seems logical and in line with Dutch law.

The combination of financial and personal guardianship is located in the first quadrant of Figure 3, quite close to the centre of the solution. This is not surprising, as over half of the analysed court files (53.8%, see Table 1) featured both financial and personal guardianship. The subgroup Care Dependents is located closest to the combination of financial and personal guardianship, as well as personal guardianship (also located in the first quadrant). Since increased needs, largely due to dementia, are a defining characteristic of the subgroup Care Dependents, it makes sense that personal guardianship is closely aligned with this subgroup. Isolated Influenceables are also located relatively close to the combination of financial and personal guardianship, indicating that the interests of some of the adults from this subgroup can be taken care of with a less intrusive alternative to full guardianship.

Financial guardianship is located in the third quadrant of Figure 3, closest to the subgroup Financial Mismanagers. The position of financial guardianship is again logical, due to the fact that the characteristics and problems of the older adults in this subgroup were mostly related to financial matters (e.g. limited understanding of finances and problematic debt).

In this study, we explored the problem constellations of older adults under guardianship in the Netherlands using data from 906 full, financial and personal guardianship court files. We conducted a thematic analysis to identify various themes emerging from the applicants’ motivations for adult guardianship and supplementary documents. These themes were then used, together with other variables like gender and age, in a multiple correspondence analysis to examine the relationships between the different characteristics of older adults placed under guardianship. We identified four profiles of older adults under guardianship, Care Dependents, Isolated Influenceables, Dangerous Avoiders, and Financial Mismanagers, each reflecting different constellations of problems. The different types of guardianship measures could also be linked to these problem constellations in a meaningful way.

One shared characteristic of a substantial number of older adults under guardianship was the unavailability of a support network to safeguard the adults’ financial and/or personal interests. Although this characteristic appeared frequently, the circumstances leading to it varied. For instance, numerous adults in the subgroup Isolated Influenceables did not have a support network due to the loss of a partner, ongoing conflicts or financial abuse by people in their network. Adults within the subgroups Care Dependents and Financial Mismanagers also experienced an absence of a support network, as their loved ones were often unable to offer assistance with decision-making due to their own health issues, being overburdened, or because they lived abroad. Social isolation among older adults is likely to increase due to demographic trends such as decreasing family sizes and a rise in complex family structures and singlehood (Brenner, et al. 2023, van der Pas and van Tilburg 2010, Chamberlain, Baik and Estabrooks 2018). This could lead to an increase in the number of older adults in need of guardianship in the future, over and above the effects of population aging. An increase in the number of older adults under guardianship without a support network could potentially create a high demand for guardians who are willing and able to take on the role, putting even more pressure on current systems (Uekert 2010). Addressing these issues warrants further research, particularly in light of the obligation placed on State Parties by the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (the CRPD Committee) to facilitate support networks for those who are isolated (Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2014).

The positioning of the Dutch guardianship measures within the MCA solution offers valuable insights into the application of these measures within the different subgroups of older adults. In the Netherlands, adult guardianship is intended as a measure of last resort, implying that individuals placed under guardianship typically face complex constellations of problems that justify such a far-reaching legal intervention. As noted in the methodology section, we were unable to draw definitive conclusions on the specific characteristics judges consider when assessing an application for adult guardianship. Nonetheless, a closer examination of the problem constellations of the four subgroups suggests that each subgroup presents its own challenges and opportunities for tailoring guardianship measures to their specific characteristics and finding alternative forms of support that fully respect the adults’ rights, will, and preferences.

For adults with a profile that typifies the subgroup of Care Dependents, restricting their legal capacity may not always be necessary, especially when they reside in a (closed) care facility. Some of the adults in this subgroup had to perform legally relevant acts, like selling their home after moving to a care facility, and they were unable to do so due to (advanced) dementia. These adults needed a legal representative to perform these acts on their behalf, which often led to an application for financial guardianship (in combination with personal guardianship). The institution of such a guardianship measure results in a limitation of the adult’s legal capacity. However, as these adults are not likely to engage in financial transactions or become a victim of fraud when residing in a care facility, this limitation of legal capacity does not seem to be entirely necessary. Other countries, such as Germany and Norway, have already introduced measures that do not automatically restrict the adult’s legal capacity, following the requirements of the CRPD. In these countries, the competent authorities are able to order a tailored restriction of legal capacity when necessary (Schuthof forthcoming). The adoption of such less restrictive measures may be beneficial for several adults within the subgroup of Care Dependents. Voluntary measures — such as the living will — may also be a viable option for some adults of Care Dependents who have children. In a living will, the adults are able to appoint one or more of their children to act on their behalf in a future period of decision-making incapacity, without a limitation of their legal capacity. A major obstacle in this regard is that a living will must be drafted in advance, as the adult needs to be capable to do so. Additionally, a living will in the Netherlands can be costly when it is drawn up at a notary’s office, and not all adults can afford it (Stelma-Roorda 2024).

Adults with a profile that matches the subgroup of Financial Mismanagers were often placed under financial guardianship. Financial guardianship can be considered a necessary legal intervention for a large number of these adults, considering their struggles with financial management. For instance, some adults ended up in debt due to a series of poor financial decisions, and the need for close monitoring of their financial behaviour left their network overwhelmed and unable to continue support. To safeguard the financial interests of these adults, limiting their legal capacity by placing them under financial guardianship seems essential. Other adults in the subgroup Financial Mismanagers could potentially benefit from a more tailored variation of financial guardianship or a less restrictive support measure, especially adults with a migration background or low literacy. Some of these adults do not need protection against their own ill-conceived decisions, but are rather in need of reliable (and low-threshold) support with managing their financial interests and may only need a legal guardian or budget manager for more complex financial matters. A living will could also potentially be an option for some of the adults in the Financial Mismanagers subgroup, provided that they have a partner, relative or someone else willing and able to provide the necessary support. Since a living will does not limit an adult’s legal capacity, the person who is awarded a CPA may face challenges if the adult persists in making adverse financial decisions. If they are unable to provide the adult with the necessary protection, financial guardianship may be the better option.

The risk of financial abuse and undue influence was substantial for many older adults with a profile that matches the subgroup Isolated Influenceables, and in certain cases, this risk was already realised (and the damage considerable). Especially adults with psychiatric disorders and/or dementia appeared to be vulnerable and were sometimes left with large financial losses, like the case mentioned in Box 2. A combination of financial and personal guardianship, and in some cases full guardianship, offers these adults the necessary protection, even more so due to the fact that the court supervises the appointed guardian. Voluntary measures like the living will present two challenges for adults in the subgroup Isolated Influenceables: they often do not have a network to support them and if they do, the people in their network may be the ones taking advantage of the vulnerability of these adults. Since no regulatory framework ensuring adequate supervision currently exists for the living will in the Netherlands, the voluntary measure may fall short of providing sufficient protection for adults in this subgroup (Stelma-Roorda 2024).

A striking characteristic of the subgroup Dangerous Avoiders is that quite a number of adults did not wish to receive any support or care. The CRPD Committee emphasized that adults with disabilities have the right to refuse support, to take risks and to make mistakes, suggesting these adults should not be subjected to adult guardianship against their will (Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2014). However, some of the adults in this subgroup did not only create unsafe situations for themselves by refusing support but also for others. As mentioned earlier, several adults in the Dangerous Avoiders subgroup exhibited dangerous behaviour like continuing to drive with an expired license, creating extremely unsafe situations for others. A full or financial guardian has the authority to sell the car of the adult involved, averting the risk of an accident. When it comes to care-related decisions, personal guardians have mentioned in previous empirical research that they are not able to provide enough protection for adults who avoid any type of care, especially when the adults fail to keep appointments (Bureau Bartels 2018). Full guardianship, which appears to be a frequently applied guardianship measure for this subgroup according to the data, would then be necessary. Alternative measures, such as a living will, are most likely no option for the adults in this subgroup, due to their voluntary nature (apart from the costs). The subgroup of Dangerous Avoiders also seems to manifest itself as a group of adults with a long history of having trouble taking care of themselves, and they may have benefited from being placed in supportive settings, such as assisted living facilities, well before being placed under guardianship.

Our final remark is that the population of older adults under guardianship is the likely the ‘tip of the iceberg’ of older adults in need of support and protection. We were only able to study older adults who were placed under guardianship after someone applied for a guardianship measure. A presumably larger group of older adults who are no longer able to fully take care of their own interests receive informal, unsupervised support from their partners, family members or others. In all likelihood, such support structures may often work well and enable adults to continue to live their lives according to their own preferences (Bijnsdorp, et al. 2019). However, in our modern digital society, older adults could end up being completely dependent on the ‘good intentions’ of their support persons. It may be very difficult for older adults to supervise or question this support, especially when they have no one else in their network (Manthorpe, Samsi and Rapaport 2012). According to a prevalence study from 2018, financial abuse was the most reported form of abuse among older adults in the Netherlands (Bakker, et al. 2018). These findings urgently call for more systematic empirical research into the support and protection of older adults.

One key limitation of this study is that we were only able to study the ‘legal reality’ of the guardianship cases in our sample. This means that we had to rely on the facts and circumstances as presented by the applicants, potentially supported by expert statements and other supporting documents. We did occasionally come across statements regarding the health condition of the adult, alleged financial mismanagement or financial abuse, which we were not able to verify with supplementary documents. However, the court staff and judges oftentimes checked the information during the oral hearing or requested further evidence from the applicant or other relevant parties. In this respect, the use of court file data can also be regarded as a strength: an independent judicial authority has been tasked with verifying the information provided.

A major strength of this study is that we used a large, systematically drawn sample of guardianship cases for each guardianship measure within multiple district courts. To our knowledge, similar systematic empirical research has not yet been conducted in the field of adult guardianship law in the Netherlands or in other European jurisdictions.

In this study, we were able to transform complex and multidimensional data from a large-scale court file analysis into an interpretable representation of the problem constellations of older adults under guardianship in the Netherlands. We distinguished four subgroups of older adults with distinctive profiles of characteristics, that related to the different adult guardianship measures in an interpretable manner. Matching the identified subgroups with the guardianship measures that have been applied to these subgroups provided interesting insights into the Dutch legal system of support and protection of older adults with impaired decision-making abilities. In the Netherlands, the application of adult guardianship measures is limited to situations where their application is necessary and treated as a last resort. It appeared, however, that for adults with particular problem constellations, more tailored, less restrictive variations of the current guardianship measures may be feasible. For other adults, voluntary measures such as the living will may be viable alternatives. However, for some adults in high-risk situations, the current guardianship measures, including full guardianship, appear the best or only safe solution.

We would like to thank the Council of the Judiciary with their help in obtaining access to the court files and all participating district courts for welcoming us, providing us with all the assistance necessary to complete the study and with their helpful insights when discussing our results. We would also like to thank the supporting researchers for their help with the data collection and data analysis, and the members of the STRIDE research project for their valuable feedback on earlier drafts.

The research was funded by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) as a part of the NWA-ORC Consortium STRIDE: Support and protection of older adults. All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Albonetti, Celesta A. 1991. “An integration of theories to explain judicial discretion.” Social problems 38 (2): 247-266.

Bakker, Leonie, Bertine Witkamp, Maartje Timmermans, Janine Janssen, and Jolanda Lindenberg. 2018. Aard en omvang ouderenmishandeling. Amsterdam: Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek- en Documentatiecentrum (WODC).

Bangma, Dorien F., Oliver Tucha, Lara Tucha, Peter P. de Deyn, and Janneke Koerts. 2021. “How Well Do People Living with Neurodegenerative Diseases Manage Their Finances? A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review on the Capacity to Make Financial Decisions in People Living with Neurodegenerative Diseases.” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 127: 709-739. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.05.021.

Belbase, Anek, Geoffrey T. Sanzenbacher, and Abigail N. Walters. 2019. “Dementia, Help with Financial Management and Financial Well-Being.” Journal of Aging & Social Policy 32 (3): 242-259. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2019.1685355.

Bijnsdorp, Femmy M., Roeline W. Pasman, Anneke L. Francke, Natalie Evans, Carel F. Peeters, and Marjolein I. Broese van Groenou. 2019. “Who Provides Care in the Last Year of Life? A Description of Care Networks of Community-Dwelling Older Adults in the Netherlands.” BMC Palliative Care 18: 1-11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-019-0425-6.

Blankman, Kees, and Rieneke Stelma-Roorda. 2023. “The Empowerment and Protection of Vulnerable Adults: The Netherlands.” Country Report. https://www.familyandlaw.eu/pagina/country_reports.

Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77-101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Brenner, Rachel, Linda Cole, Gail L. Towsley, and Timothy W. Farrell. 2023. “Adults without Advocates and the Unrepresented: A Narrative Review of Terminology and Settings.” Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine 9: 1-8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/23337214221142936.

Bureau Bartels. 2018. Werking wet wijziging curatele, beschermingsbewind en mentorschap, Besluit kwaliteitseisen cbm en Regeling beloning cbm. Final Report, Amersfoort: Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek- en Documentatiecentrum (WODC).

Catlin, Casey C., Heather L. Connors, Pamela B. Teaster, Erica Wood, Zachary S. Sager, and Jennifer Moye. 2022. “Unrepresented Adults Face Adverse Healthcare Consequences: The Role of Guardians, Public Guardianship Reform, and Alternative Policy Solutions.” Journal of Aging & Social Policy 34 (3): 418-437. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2020.1851433.

Chamberlain, Stephanie, Sol Baik, and Carole Estabrooks. 2018. “Going it Alone: A Scoping Review of Unbefriended Older Adults.” Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue canadienne du vieillissement 37 (1): 1-11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980817000563.

Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. 2014. General comment No. 1 - Article 12: Equal recognition before the law. CRPD/C/GC/1.

de Kievit, Femke M. 2024. Het bevorderen van familie- en mantelzorg in beleid en regelgeving. The Hague: Boom.

Gifi, Albert. 1990. Nonlinear multivariate analysis. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Kim, Hyejin, and Mi-Kyung Song. 2018. “Medical Decision-Making for Adults Who Lack Decision-Making Capacity and a Surrogate: State of the Science.” American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine 35 (9): 1227-1234. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909118755647.

Lê, Sébastien, Julie Josse, and François Husson. 2008. “FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis.” Journal of Statistical Software 25 (1): 1-18. doi:https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v025.i01.

Manthorpe, Jill, Kritika Samsi, and Joan Rapaport. 2012. “Responding to the Financial Abuse of People with Dementia: A Qualitative Study of Safeguarding Experiences in England.” International Psychogeriatrics 24 (9): 1454-1464. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610212000348.

Mascini, Peter, Irene van Oorschot, Don Weenink, and Gratiëlla Schippers. 2016. “Understanding Judges’ Choices of Sentence Types as Interpretative Work: An Explorative Study in a Dutch Police Court.” Recht der Werkelijkheid 37 (1): 32-49.

McSwiggan, Sally, Susanne Meares, and Melanie Porter. 2016. “Decision-Making Capacity Evaluation in Adult Guardianship: A Systematic Review.” International Psychogeriatrics 28 (3): 373-384. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610215001490.

Näkki, Kaisa, Anna Mäki-Petäjä-Leinonen, Kaijus Ervasti, and Eino Solje. 2024. “Evaluating the Need for Legal Guardianship in People with Dementia: Gaining Insight into Professionals' Assessment Criteria.” International Journal of Law, Policy and The Family 38 (1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/lawfam/ebae005.

Nieuwboer, Roos, Catrien C. J. H. Bijleveld, Wendy M. Schrama, and Masha V. Antokolskaia. forthcoming. “De Rechtspraktijk van Curatele, Beschermingsbewind en Mentorschap bij Oudere Personen in Beeld.” Recht der Werkelijkheid.

Nwakasi, Candidus C., and Amy R. Roberts. 2022. “Older Adults under Guardianship: Challenges and Recommendations for Improving Practice.” Journal of Aging & Social Policy 34 (3): 401-417. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2021.1926198.

Officer, Alana, Jotheeswaran Amuthavalli Thiyagarajan, Mira Leonie Schneiders, Paul Nash, and Vânia de la Fuente-Núñez. 2020. “Ageism, Healthy Life Expectancy and Population Ageing: How Are They Related?” Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (9): 3159. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093159.

Quinn, Mary Joy, Lisa Nerenberg, Adria E. Navarro, and Kathleen H. Wilber. 2017. “Developing an Undue Influence Screening Tool for Adult Protective Services.” Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect 29 (2-3): 157-185. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08946566.2017.1314844.

Rovers, Sonia D. 2023. “Implementation of Article 12 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in the Netherlands.” In Models of Implementation of Article 12 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), by M. Domański and B. Lackoroński, 339-370. London: Routledge.

Sager, Zachary, Casey Catlin, Heather Connors, Timothy Farrell, Pamela Teaster, and Jennifer Moye. 2019. “Making End-of-Life Care Decisions for Older Adults Subject to Guardianship.” The Elder Law Journal 27 (1): 1-34.

Schuthof, Fiore S. forthcoming. “Promoting Autonomy in Adult Guardianship Measures: A Comparative Analysis of CRPD and ECtHR Human Rights Requirements in 28 European Jurisdictions.” Family & Law.

Stelma-Roorda, Rieneke. 2024. In Anticipation of a Future Period of Incapacity: The Dutch 'Levenstestament' from a Legal, Empirical and Comparative Perspective. The Hague: Eleven International Publishing.

Tombs, Jacqueline, and Elizabeth Jagger. 2006. “Denying Responsibility. Sentencers’ Accounts of their Decisions to Imprison.” British Journal of Criminology 46 (5): 803-821. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azl002.

Tompkins, Joanne, Heather Connors, and Diane Robinson. 2024. “Seize the Data: An Analysis of Guardianship Annual Reports.” Journal of Aging & Social Policy 1-18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2024.2349494.

Uekert, Brenda K. 2010. Adult Guardianship Court Data and Issues: Results from an Online Survey. Williamsburg, VA: National Center for State Courts.

van der Pas, Suzan, and Theo G. van Tilburg. 2010. “The Influence of Family Structure on the Contact between Older Parents and Their Adult Biological Children and Stepchildren in the Netherlands.” Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 65 (2): 236-245. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbp108.

van Oorschot, Irene, Peter Mascini, and Don Weenink. 2017. “Remorse in context(s): A qualitative exploration of the negotiation of remorse and its consequences.” Social & Legal Studies 26 (3): 359–377. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0964663916679039.

World Health Organization. 2023. Progress report on the United Nations Decade of Healthy Ageing, 2021-2023. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

Department of Private Law, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Netherlands Institute for the Study of Crime and Law Enforcement, r.nieuwboer@vu.nl, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4252-1042.↩︎

Department of Criminology, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Netherlands Institute for the Study of Crime and Law Enforcement, Cbijleveld@nscr.nl, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2455-533X.↩︎

Department of Private Law, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, m.v.antokolskaia@vu.nl, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6452-7587.↩︎

Department of Private Law, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, m.i.schaap@student.vu.nl.↩︎

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2006 A/RES/61/106. According to Article 1 of the CRPD, persons with disabilities include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.↩︎

See Declarations and Reservations, United Nations Treaty Collection, Chapter IV Human Rights, 15. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, https://treaties.un.org/pages/viewdetails.aspx?src=treaty&mtdsg_no=iv-15&chapter=4&clang=_en#EndDec, accessed May 9, 2025.↩︎

Article 7:450 of the Medical Treatment Act also provides a legal basis for adults to draft a so-called ‘negative treatment directive’, which is an advance directive in which certain medical treatment is refused by the adult.↩︎

Some exceptions can be found in Dutch law, for example that an adult under full guardianship can initiate procedures concerning the guardianship measure and submit an appeal against the decisions made by the court (Article 1:381 DCC).↩︎

Financial guardianship can also be instituted when an adult is temporarily unable to take care of his or her financial interests as a result of prodigal behaviour or problematic debts (Article 1:431 DCC).↩︎

In compliance with data-sharing agreements and to protect the identities of the older adults under guardianship, district court names have not been included in the study.↩︎

For each list, the total number of court files was divided by 100 (plus an additional margin to account for potential missing court files) to determine the interval between the files to be selected. The starting point was determined each time using a random number between one and the first interval.↩︎

The scoring form is available from the authors upon (reasonable) request.↩︎

We excluded subthemes that were present in less than 1.5% of the court files from the dataset used for the MCA, as these subthemes were rare and we were cautious not to overload the model. Inclusion of these rare subthemes led to a so-called degenerate solution (i.e. a solution that is technically satisfactory but substantively useless as it capitalises on a small number of rare characteristics that cluster strongly). After we removed these subthemes, it emerged that two guardianship cases distorted the solution because of their extremely rare combinations of characteristics. These two cases were also removed.↩︎

Applicants were only asked to list the siblings of the older adult if they had no partner or adult children. It is therefore likely that the actual percentage of adults with siblings is higher. Some court files contained information from the Personal Records Database (‘Basisregistratie Personen’), allowing us to confirm the partner, children, and siblings listed on the application form.↩︎

In the Appendix, we included a passage from one of the court files for each subtheme (see Table 3).↩︎

The variable category ‘Dementia’ is not located within Isolated Influenceables, but the variable category ‘Combinations of Conditions’ was often a combination of a psychiatric disorder and a type of dementia. Additionally, the subgroup Isolated Influenceables is located relatively close to the subgroup that is characterised by ‘Dementia’ (Care Dependents).↩︎