Information Research

Vol. 30 No. 2 2025

Expanding Wilson’s information behaviour model using social cognitive theory: A case study

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/ir30251418

Abstract

Introduction. The purpose of this paper is to expand Wilson’s information behaviour model using social cognitive theory and demonstrate its use in understanding information seeking and sharing of doctoral peers in unstructured environments.

Method. In this qualitative study, data was collected using twenty in-depth, semi-structured interviews of doctoral students in the social sciences and humanities disciplines.

Analysis. The interview data was transcribed, imported into the ATLAS.ti software, and coded using thematic analysis.

Findings. The findings demonstrate, first, that the intervening variables of the information behaviour model can fall under person and environment categories of social cognitive theory. Second, most of the variables (i.e., psychological, interpersonal/role related, source characteristics, and environment) can be found in information seeking and sharing behaviour of doctoral peers. Finally, person, environment, and behaviour factors have a reciprocal impact on one another. The environment category is discussed in this paper.

Conclusion. This paper demonstrates that social cognitive theory can successfully expand the information behaviour model and make it adaptable to the context of information seeking and sharing among doctoral peers in unstructured environments.

Introduction

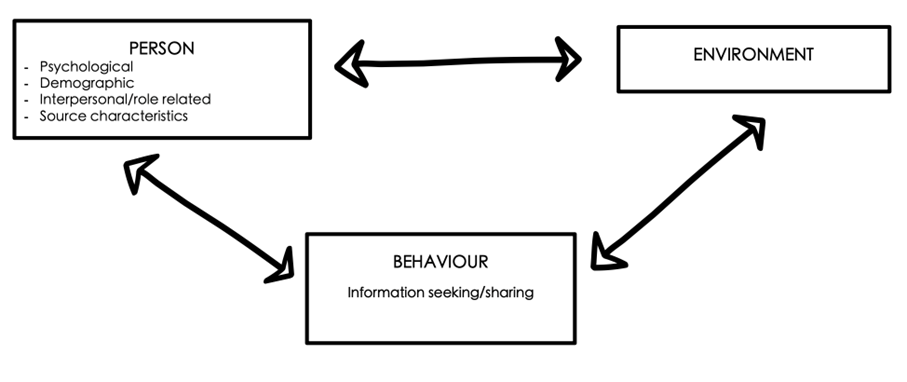

Despite being developed in the field of information science, the information behaviour model has proven to be a versatile model that can be applicable to various contexts and disciplines, with examples ranging from healthcare (Muusses et al., 2012) to education (Ford, 2004). The information behaviour model recognises that a feeling of uncertainty creates an information need, which prompts engagement in information seeking behaviour. In pursuit of information, certain variables can foster or impede information seeking behaviour. The 1997 iteration of the model (Wilson, 1997) incorporates several theories, such as stress/coping theory, risk/reward theory, social learning theory, to provide a holistic understanding of the process. One of these theories, social learning theory by Bandura (later renamed to social cognitive theory), is found in information behaviour for its concept of self-efficacy (i.e., one’s belief in their ability to find and use information). The information behaviour model recognises that self-efficacy can determine an individual’s choice to pursue information. Social cognitive theory, from the field of psychology, is concerned with understanding human behaviour and focuses on the interplay between person, environment, and the behaviour. Specifically, it postulates that factors related to the person, the environment, and the behaviour can have reciprocal impacts on one another (triadic reciprocal determinism) (Bandura, 1986). With Wilson explicitly mentioning self-efficacy as social cognitive theory’s contribution to information behaviour, it is easy to overlook its other aspects. However, in this paper, it is demonstrated that social cognitive theory’s value to information behaviour goes beyond self-efficacy and can further complement Wilson’s model by providing a guideline for its intervening variables.

As part of the research conducted for a completed doctoral dissertation examining the information behaviour of doctoral students (Montazeri, 2024), this study used Wilson’s information behaviour model as a blueprint to better understand the factors that may influence information seeking and sharing among doctoral peers in unstructured environments (i.e., environments where interaction and information seeking and sharing with peers are not planned). While information behaviour provided a starting point, its intervening variables required additional guidance to form a solid foundation for understanding the information behaviour of doctoral peers. Social cognitive theory, with its focus on the reciprocal interaction of environment, person, and behaviour, was able to provide such a guideline. Accordingly, the intervening variables were mapped onto social cognitive theory’s categories, and the concept of reciprocal determinism, as opposed to a linear effect, was adopted (see Figure 1). The dissertation on which this paper is based explores the types of information exchanged among doctoral peers, factors that could influence their information seeking and sharing behaviour, and the perceived usefulness of peers as an information source. This paper focuses on the environment category of factors impacting information seeking and sharing, and on how social cognitive theory complements the information behaviour model.

Figure 1. Reciprocal interaction of person, environment, and behaviour.

Methods

To explore information seeking among doctoral peers in unstructured environments, a qualitative approach was employed. Twenty in-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted during 2021 and 2022 among social sciences and humanities students at McGill University in Montreal, Canada. This population was chosen as they often work in isolation with little requirement of interaction with peers. Moreover, they are often faced with a lack of information, which creates an information need (Lovitts, 2001). The interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded using the thematic analysis technique in the ATLAS.ti software (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The study was approved by the McGill University Research Ethics Board two (Research Ethics Board file #: 21-07-047) and all participants provided informed consent prior to participation.

Findings

The findings successfully demonstrate the complementary nature of social cognitive theory to information behaviour. In general, most of the intervening variables are present in social cognitive theory. In addition, the theory’s focus on the reciprocal impact of environment, person, and behaviour is shown in information behaviour, making it applicable to studying information seeking and sharing in unstructured environments. The comprehensive discussion of the findings is beyond this paper and can be found in the author’s doctoral dissertation (Montazeri, 2024). Consequently, only the factors related to the environment are explored below.

Environment

Both Wilson and Bandura see environment as context-dependent and provide examples to illustrate it. Wilson’s information behaviour model recognises the seeker’s environment as a variable that can both encourage or discourage information seeking. He demonstrates environment by providing examples related to time, location, and culture (Wilson, 1997). Like the information behaviour model, social cognitive theory recognises environment as having social and physical facets. The former is related to the people, while the latter can be related to the physical space. Social cognitive theory also implies that a person involved in a behaviour, by virtue of their actions, can construct their own environments (Bandura, 1986). These elements of social cognitive theory were able to provide a more defined guideline for information behaviour to use in this study. Here, the environment was directly related to the institution affiliated with the student. Examples of institutions include the university, faculty, and department. The findings revealed environment as access to peers and resource availability.

Access

Access to peers was established by sharing the same programme component(s), being in the same physical space, referrals, events, and programmes. A shared programme component included any part of the doctoral programme that was shared among students. Examples included classes, seminars, and workshops. These introduced students to their peers and informed them of which peers to go to for information. Specifically, students were able to learn about their peers’ research areas and skills. For instance, when asked about how they met the peers they typically turn to for information, Participant 12 explained:

… I think at that point, mainly through seminars that we'd taken together. I think both of them were in, I think all three of us were in at least one, possibly two of the same seminars in our first semester. So, I was aware of what they're working on just because people talk about their research and that kind of context.

Physical space also contributed to information seeking and sharing. Specifically, being in the same space often sparked spontaneous conversations among peers that led to exchange of information. Physical spaces included student office space, computer lab, and the student lounge. Participant 19 described physical space and their encounter with peers as:

So in the department, we do not have any office. But we have a common lounge slash lab, there's a lab which has computers, so we can go there. And that's where I meet the other people from my cohort, as well as people in the PhD program in various years. And so that's where the main interaction would happen between us PhD students. So, we'd be discussing our research and coursework or whatever else.

Referrals by those in the department (i.e., institution) were another way to access peers. Doctoral students interviewed described cases where they had either reached out to an individual in the department or others had contacted them for information on a particular topic. For example, Participant 15 had reached out to the head of the department to get connected with others who were also applying for the same grant. In the case of Participant 10, a referral had not only addressed their information need but led to a long-lasting friendship.

In addition to referrals, institution-related events, such as orientation, and programmes, such as student buddy programme, were some of the other ways of getting to know peers. An example was Participant 18, who talked extensively about one of their close friends they had met through the student buddy programme (i.e., a programme that matches incoming students with one another). In this case, the connection with their buddy was sustained and had resulted in a close friendship. The two would often interact and exchange information both inside and outside of the school environment.

Resource availability

Resource availability was related to the availability of information and support. Overall, the less available the resource, the more likely it was for participants to go to peers. For instance, Participant 2’s supervisor was on maternity leave and unable to provide the support they needed. As a result, the participant relied on their peers, whom they called ‘a resource and a tool in my toolbox’ to indicate their value. Similarly, Participant 5 recalled going to a peer for a course syllabus when they could not find the document on the department’s website.

Access and resource availability can individually, or together, encourage or discourage information seeking. For example, Participant 20 mentioned, ‘I didn't particularly feel like I could get good information from my supervisor’ as a rationale for seeking information from a peer (i.e., lack of resource), whom they had come to know through the department (i.e., access).

Discussion and conclusion

A strength of Wilson’s information behaviour model is its adaptability to various contexts. In this study, the information behaviour model provided a starting point; yet its intervening variables needed a guideline for understanding information seeking and sharing of doctoral peers in unstructured environments. Social cognitive theory was used to complement the variables and placed them under the person or the environment category. The latter was the focus of this paper, which expanded to access and resource availability.

The findings highlight the important role the environment plays in encouraging information seeking and sharing among doctoral peers, as well as the significant influence institutions have in shaping that environment. Consistent with social cognitive theory, it was also observed that the behaviour (i.e., information seeking/sharing), environment, and the person can influence one another. For example, an environment with easy access to peers encourages a student to engage in information seeking, which further promotes an information seeking environment. If the behaviour is proven to be positive, it promotes a sense of closeness, a personal factor, which allows for future information seeking. The same influence can also be negative. For instance, lack of closeness with peers might discourage information seeking, which creates a barren environment.

It is hoped that this expansion of the information behaviour model demonstrates how information behaviour and social cognitive theory complement one other to understand information seeking and sharing of doctoral peers in unstructured environments and promote its further applicability to other contexts.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the participants for sharing both their valuable time and experiences. I also wish to thank Dr. Jamshid Beheshti for generously providing helpful guidance and comments on this paper. Finally, I would like to acknowledge the support of Dr. Joan Bartlett.

About the author

Peymon Montazeri is a graduate of McGill University in Montreal, Canada, where he obtained his PhD in Information Studies. His research interests include information seeking, information sharing, and information use. Peymon can be reached at peymon.montazeri@mail.mcgill.ca.

References

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Pearson.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Ford, N. (2004). Towards a model of learning for educational informatics. Journal of Documentation, 60(2), 183–225. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410410522052

Lovitts, B. E. (2001). Leaving the ivory tower: The causes and consequences of departure from doctoral study. Rowman & Littlefield.

Montazeri, P. (2024). Information seeking and sharing among doctoral peers: An exploratory case study in the context of skills [McGill University]. https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/theses/3t945x515

Muusses, L. D., van Weert, J. C. M., van Dulmen, S., & Jansen, J. (2012). Chemotherapy and information-seeking behaviour: Characteristics of patients using mass-media information sources. Psycho-Oncology, 21(9), 993–1002. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1997

Wilson, T. D. (1997). Information behaviour: An interdisciplinary perspective. Information Processing & Management, 33(4), 551–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4573(97)00028-9

Copyright

Authors contributing to Information Research agree to publish their articles under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which gives third parties the right to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format. It also gives third parties the right to remix, transform and build upon the material for any purpose, except commercial, on the condition that clear acknowledgment is given to the author(s) of the work, that a link to the license is provided and that it is made clear if changes have been made to the work. This must be done in a reasonable manner, and must not imply that the licensor endorses the use of the work by third parties. The author(s) retain copyright to the work. You can also read more at: https://publicera.kb.se/ir/openaccess