Information Research

Vol. 30 No. 3 2025

All the signs we cannot see: understanding the complexity of space experiences with Photovoice

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/ir30354557

Abstract

Introduction. This paper investigates student experiences in various campus spaces to understand the physical and environmental qualities that create a welcoming climate or facilitate a sense of belonging for students.

Method. Two rounds of the photovoice method were completed with two groups of students. Each group of students participated in an informational meeting, a period of taking photographs, and a final discussion meeting. Students captured images of spaces they visited for different purposes, from extended study to passing the time while waiting for others.

Analysis. Photographs, written photograph comments, meeting transcripts, and researcher notes were analysed for recurring themes and concepts students placed particular emphasis on during discussions. Student participants were engaged in the analysis process during the final group discussion meetings.

Results. The following six recurring themes were identified as having significant impact on students’ experience of spaces: signage; space expectations; utility; furniture, aesthetics and ambience; convenience; and homeness.

Conclusions. While the results mirror those found in similar studies, participatory research methods allow for a deeper understanding of student experiences that have implications for both participants and researchers.

Introduction

Amid returning to in-person academic activities after pandemic social distancing, campus closures and growing social unrest across the United States, colleges and universities started focusing on a more holistic approach to supporting students, especially those from historically underrepresented backgrounds. As a result, the literature exploring what creates a sense of belonging for students on college campuses is growing. For libraries, this has resulted in broadening our assessment of spaces from what students want, or need. in library spaces (outlets, comfortable seating and access to food), to also considering what features might contribute to this sense of belonging and how libraries can create welcoming spaces.

At the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign University Library, this desire to better understand student needs was further complicated by a library building project with two major goals for developing spaces within our complex, multi-branch university library system. The first goal was to transform the Undergraduate Library building, a branch library built in 1966 to support the rapid growth of undergraduate education, to a state-of-the-art facility that hosts special collections and archives. The second goal focused on strengthening student success services and renovating spaces in the main library building and beyond, to support various facets of student life, from studying to wellness. The proposed closure of the Undergraduate Library received both strong support and criticism from faculty, staff and students. On May 13th, 2022, the Undergraduate Library officially closed, and its services were dispersed throughout other library locations, including to a dedicated space in the main library. Student comments about the closure indicate that for many, the closure of the Undergraduate Library reduced the availability of student-focused spaces and increased the difficulty of locating a place to study.

In an effort to understand user perceptions and needs, the University Library has a long history of evaluating physical library spaces through informal and formal measures. We have conducted off-the-shelf user surveys LibQUAL+Ⓡ/LibQUAL+Ⓡ Lite and Ithaka S+R Faculty/Graduate/Undergraduate surveys that have space assessment components. We have also conducted locally designed surveys and guerrilla style UX studies on space use. However, owing to our distributed nature, with multiple libraries across campus, these assessments are typically specific to a single space; a newly renovated commons area, a branch library embedded in a disciplinary building, or the entirety of a stand-alone library building. While this feedback is valuable, it offers us little insight into how students identify and perceive spaces on campus and across the libraries in a way that lets us develop more welcoming and inclusive spaces. Furthermore, how do we understand the experiences of those who are part of historically marginalised groups?

Past studies conducted by the University Library relied on random sampling or convenience sampling and had limited results from students of colour, international students, or students with different learning abilities. A University of Illinois Student Affairs survey (2021) found that only 55% of students felt connected to the University. With respect to certain social groups on campus (e.g., friends, student organisations), underrepresented minority students reported feeling less connected compared to students of other demographic groups. Lastly, much of the past space assessments centred on the physical environment and tangible aspects, not on the experiences of locating and making use of campus spaces. In doing so, past space assessments implicitly narrowed the concept of user satisfaction to the physical qualities of a space (e.g., size, furniture or coffee shop) and left open the question of how spaces affect their sense of connection to the broader campus community.

This paper reports an exploratory qualitative study using the participatory research method, photovoice, to centre and forefront student voices in developing our understanding of their space needs. Working with two groups of students over the course of two semesters, this study aims to help develop our understanding of how students experience campus study spaces. The photovoice method allows us to share the rich dialogue between students and to present both the tangible and intangible aspects of space that are important from the student perspective. While our findings echo those of other studies (students want convenient spaces with the features needed to accomplish their tasks), this study also emphasises the importance of communication through signs and other visual means, unintentional messages sent through space-related choices and the impacts of flexibility on student experience in spaces. Additionally, this study goes beyond reporting findings by also considering the transformative impact participatory research can have on the researchers themselves.

Literature review

Photovoice as a method was first proposed by Wang and Burris (1994) in healthcare fields and has since grown in popularity in many disciplines. Latz’s (2017) Photovoice research in education and beyond: a practical guide from theory to exhibition positioned the method within education research and provided a detailed manual for using the photovoice method, outlining steps and considerations throughout the entire process. Luo (2017) argued the value of photovoice as a method for library and information science research while also providing a primer to the method. At the time, Luo only identified three library science studies that had used the photovoice method. Julien et al. (2013), one of the three studies identified, reflected on the method and argued that library staff who conduct user research are often outsiders with regards to the studied community, but that photovoice heightens the validity of participants’ responses because:

the photographs used to elicit responses are not those taken by community outsiders (e.g., the research team or professional photographers); instead participants are empowered to choose those images they think are worthy of capturing’ (p. 261).

The photovoice method has been used in library and information science research to inform information literacy (Julien et al., 2013; Lloyd & Wilkinson, 2016), understand student perceptions of academic integrity (Click, 2014) and to better understand how students seek information to improve reference services (Tewell, 2019).

Since Luo’s 2017 paper there has been growth in library and information science studies using photovoice, especially when it comes to using the method to understand student experience in library spaces. Beatty et al. (2020) used photovoice to understand how indigenous students ‘experience their learning in informal library spaces and elsewhere on campus’ (p. 4), while Chapman et. al. (2020) used the photovoice method along with discussion groups and survey data to understand the experience of Black students at Duke University. The latter found that the library spaces, while ‘not actively hostile or racist, are complicit in their silence’ (p. 2). Poljak et al. (2023) used photovoice to identify physical features of library spaces that contribute to a feeling of welcome and belonging in a diverse student population. Other studies have engaged similar methods that require participants to photograph their spaces, such as the photo elicitation method (Haberl & Wortman, 2012; Neurohr & Bailey, 2016; Newcomer et al., 2016). A number of these studies used photovoice intentionally to emphasise the voices of marginalised or underrepresented students (Beatty et al., 2020; Chapman et al., 2020; Poljak et al., 2023; Tewell, 2019).

Developing spaces that make all students feel welcome and that help create a sense of belonging on campus has been a growing concern for academic libraries. In Designing libraries for the 21st-century, Joan K Lippincott discussed how to enhance students’ sense of belonging through a variety of spaces and the importance of focusing on the whole student, from spiritual and emotional wellness, to factors that contribute to physical safety (2022). Studies have explored creating these spaces for specific student identities, from first-generation students (Couture et al. 2021, Schultz et al. 2023) to parenting students (Keyes 2017, Scott & Varner 2020). Poljak et al.’s (2023) study focused on the features of spaces that create a sense of belonging in students, finding that those features that help create a sense of physical safety, emotional well-being, emotional safety and ownership contribute significantly. This concept of ownership was also found in Bucy’s (2022) study that included interviews with Native American undergraduates. Bucy found that Native American students felt a sense of belonging where their identity was reflected and valued visible representations of Native Americans. Chodock (2021) used photo elicitation with a diverse student group and observation data to map physical library spaces to four facets of sense of belonging (psychological, spatial, cultural and sociocultural), demonstrating how the academic library can be a place where they feel they belong. Others have relied on survey data to identify the factors that impact how welcoming students of colour find library spaces (Elteto et al., 2008).

Bodaghi and Zainab’s (2013) study of visually impaired students and their sense of belonging and inclusion in academic libraries found that carrels were considered a second home, where the students felt safe, comfortable, and accepted. This concept of homeness was further explored by Mehta and Cox (2021). Their study utilised a mixed method approach to further explore the concept of homeness in academic libraries and how design might impact it. They found several implications for library design, from the importance of the basics, such as an ability to eat and drink and access to space, computers and power; to the idea that familiarity creates more comfort, meaning older designs might be considered a warmer atmosphere. Mehta and Cox reiterated that ‘constant innovation could cause the space to lose the sense of stability that libraries often provide’ (2021, p. 29).

To address the changing needs of students, a variety of assessment methods and theories have been applied to understand how students use, or want to use, academic library spaces. Andrews et al. (2016) outlined a variety of qualitative and quantitative methods used to redesign a branch library at Cornell University. Their assessment methods from 2006-2014 included space observations, surveys, interviews, usability tests and surveys, environmental scan and visits to other facilities, photo diaries, ideal-space design exercises, working with students in the Design and Environmental Analysis department and focus groups. Their results mirrored what could be found in the literature; finding that library spaces tend to inspire students to study, but that they have a desire for flexible and integrated technology in those spaces, with a variety of available furniture and types of spaces, spaces that preferably have clearly articulated noise levels (Andrews et al., 2016). Diller and Wallin (2023) also relied on a variety of methods, both formal and informal, with a goal of understanding whether place attachment, affordance, and attention restoration theories can be helpful in designing more effective study spaces. Andrew McDonald’s The Ten Commandments revisited: the qualities of Good Library Space (2006) identified adaptable, flexible spaces as one of the key qualities of good library spaces. An adaptable space is an attempt at future proofing the space, guaranteeing the ability to meet unknown future needs. However, responsibly managing our resources and creating flexible spaces can sometimes be in conflict with creating spaces where students know what to expect, either in how they can/can not move the furniture, or the anticipated noise levels. As Diller and Walling noted:

Students identify the library as a place to study, and they rely on the library and those within it to reinforce the discipline of study. For the library to provide this valued service, it must maintain the essential look and feel of what students associate with an academic library… although they may never use the books on the shelves, they want to see books, which are a key to the symbolic meaning and schema of a library (2023, p. 709).

While innovation and flexibility in library spaces is an often-desired feature, it can also create unanticipated tensions.

Study design

The study presented was one of many efforts conducted by the University Library to develop a holistic understanding of student needs for library spaces that was guided by the University Library’s Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility vision (University Library, n.d.). The University Library used several methods to accomplish this goal, including an analysis of social media content, review of previous survey data, conducting focus groups and a photovoice study. As previous University Library studies lacked data from the underrepresented demographics, and to align with the Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Accessibility vision, coordinated efforts were made to recruit participants through student organisations and student affairs programs. The photovoice method was selected because it is a participatory research method, where participants are seen as co-researchers involved in developing the research prompts and involved in subsequent analysis to some extent, ensuring that participant voices (student voices, in this case) are prioritised and heard. Participants take photos during their day-to-day lives to capture their experiences as they relate to the research prompts, then come together as a group to discuss them. The research team for this study broke down the process to three research activities. Each research activity was conducted with the fall 2022 and spring 2023 participants.

Information meetings: the information meetings were conducted using the video conferencing software Zoom (licensed by our institution) and used to introduce the participants to the study process and goals. Each participant received a packet with study details and expectations (Appendix A). Research team members took notes during the information meetings, and the meetings were recorded using the University-licensed Zoom.

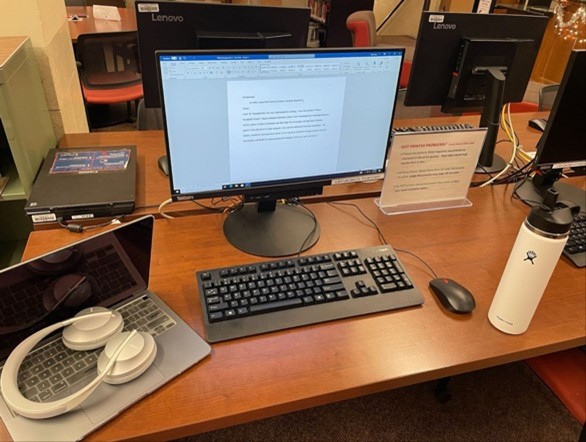

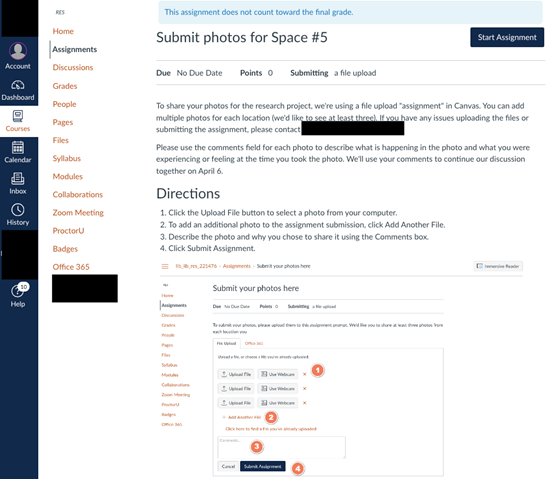

Taking pictures: asynchronously during the six weeks after the information meetings, participants took pictures using their own smartphones and uploaded the pictures into the Canvas collaboration space. Canvas is a course management system licensed by the institution. See Appendix B for a sample Canvas collaboration space page.

Discussion meetings: the discussion meetings were conducted using the University-licensed Zoom. The same research team members used the Photovoice Discussion Guide (Appendix C) to guide the meetings. The team members took notes during the meetings and the meetings were recorded using the University-licensed Zoom.

Participants were compensated for each phase they completed and could receive up to $100: receiving $30 for the information meeting; $30 for taking pictures; and $40 for the discussion meeting. Because involvement in this study required ongoing participation from the participants during the academic year and they were seen as co-researchers, we believed that it was important to compensate the students fairly for their time and intellectual labour.

The photovoice study occurred in two separate rounds. Five students originally signed up to participate in the fall 2022 round, and three students fully participated in the study. Two participants self-identified as persons of Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin and the other participant self-identified as Asian. A total of twenty-six pictures were submitted by the participants. Eight students signed up to participate in the spring 2023 round, and five students fully participated in the study. Among the five spring 2023 participants, two self-identified as Black or African American, one self-identified as Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin, one self-identified as Asian and one self-identified as White. In total, five of the eight participants came from what the University considers as underrepresented minority groups at the institution. There were no participants who are Native American/Alaskan or Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. The number of participants from underrepresented student groups reflected the university enrolment demographics (https://dmi.illinois.edu/stuenr/abstracts/FA24_ten.htm).

A total of fifty-four pictures were submitted. At the conclusion of each semester’s study, participants were given the option to choose how they were identified for their contributions. These options included being identified by their first name, being identified by a pseudonym they selected and believed represented their identity, or being identified by a pseudonym created by the research team. Because we saw the student participants as co-researchers, it was important they were given the opportunity to have their identity and voices faithfully represented and not be reduced to participant A.

While the three students that completed the fall 2022 round did participate fully, this experience felt forced and heavily focused on existing library features. We believe this was likely because of the defined photography prompts generated during the information meeting, with words like entrances, décor, or location. Based on that observation, in spring 2023 we instead asked participants to take three different photos of a space where they were working, and to take photos of at least three different spaces in total. By not focusing on specific criteria or features this allowed participants to document their individual experience and emphasise the features that stood out to them. During the initial informational meeting, we also showed participants in the spring 2023 round a picture from the fall 2022 participants and demonstrated the discussion process that would occur later. We believed this approach resulted in higher participation and more robust discussion with participants.

| Fall 2022 Prompts | Spring 2023 Prompts |

|---|---|

|

|

Table 1. Photography prompts

Participants photographed fifteen physical spaces across campus, seven of which were library spaces (see Table 2). The library spaces photographed included several spaces within the main library building, from gallery areas to the reading room, and three other branch libraries. The eight non-library spaces photographed included a new design facility, the student union, a resource centre and disciplinary buildings (e.g., the Sidney Lu Mechanical Engineering Building).

| Library spaces | Non-Library spaces |

|---|---|

|

|

Table 2. Campus locations photographed by participants

The discussion meetings with participants were an important aspect of the analysis process. While participants introduced their photographs and shared why they photographed the space, they were also prompted to discuss how, when and why they visited those particular spaces. As discussion continued and more photographs were introduced, we encouraged participants to identify aspects of the spaces that were similar across their experiences and to respond to each other’s photographs. The research team met after the discussion meetings to continue analysis on the meeting transcripts and notes, paying attention to the importance placed on different themes by the participants, in addition to how pervasive various themes were across photographs and discussions. Participant photographs were also reviewed for repetitive content. These efforts resulted in the themes presented in the findings.

Findings

While the goals of the University Library, as well as the design of the photovoice study, were structured to broadly gather feedback specific to students’ space needs during a period of building transformation projects, we also emphasised the myriad ways spaces signal a sense of utility, welcoming, belonging and safety to students, through analysis of the photovoice data. In both rounds of the study, the students’ photos and subsequent discussion, on effective and ineffective spaces alike, demonstrated the complexity of how intangible phenomena are measured. Their photos and comments reinforced that while there is not a singular vision for use of, or belonging, in third spaces, there are themes that broadly appeal to a wide spectrum of student needs. Through this process, we identified in the students’ photographs and conversation transcripts six notable themes by flagging resonance of discussion topics that elicited enthusiastic student participation and commentary, as well as frequency of topic occurrence. These six themes are: signage; space expectations; utility; furniture, aesthetics, and ambience; convenience; and homeness.

Signage

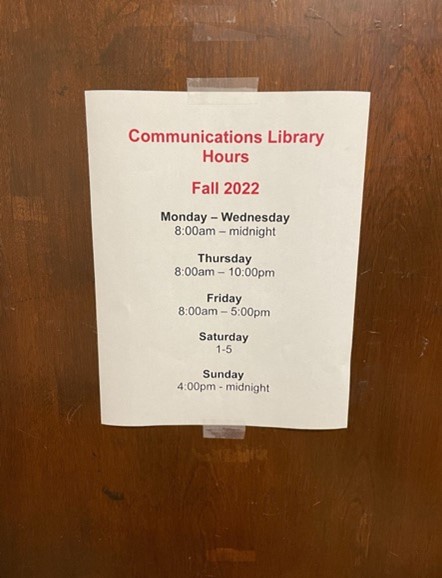

Participant photos often included signage that was used to communicate a variety of information, including hours and available resources. The participants also focused on the design of the signs. Participants observed that poorly designed signs might imply employees did not care to exert more effort than minimally required, were not adequately supported to deliver a polished final product, or that the information shared was not important, as demonstrated in Figure 1. For some, signage helped create a feeling of welcoming (or lack thereof), especially for specific identities (for example, signs for all-gender bathrooms and their availability). Participants also indicated that signage needs to be appropriately sized to communicate the message and not everything should be printed on 8.5x11 paper.

Moreover, participants highlighted that signs can foster a sense of exclusion: Sreelakshmi created a collage of bathroom signs in the natural history building (Figure 2), showing how, on most floors, there were male and female designated restrooms, with direction to the single floor with an all-gender restroom being little more than a ‘footnote’. Sreelakshmi was frustrated, both by the limited restrooms that met their needs, and further excluded by the way in which this message was communicated through the signage.

Figure 1. A photograph taken by Irene of a library sign that was printed on 8.5x11 paper with inconsistent formatting.

Figure 2. A collage of restroom signs from each floor in a building. Sreelakshmi wanted to show the unwelcoming message the signs display and the lack of all-gender restrooms on most floors.

Lastly, while discussing confusing signage, participants in spring 2023 branched into a discussion on the challenges presented by navigating large, complex library buildings, such as Daniel’s observation of the Funk Library’s architecture as ‘confusing’. This aside reinforced the need for accurate and consistent signage across the library system, not only for hours, but basic wayfinding.

Space expectations

Participants valued knowing how a space is intended to be used, especially when it is a new space to them. It can be hard to know the social rules of a space, so there was a need identified for the library to communicate this visually. The spring 2023 participants discussed at length the unknown purpose of various spaces within the Illini Union, including the lower level that is used both as a food court and as a study space, shown in Figure 3. People tended to leave the tables dirty when they did eat there, and students awkwardly spaced themselves out amongst the tables when eating or studying.

Figure 3. Daniel’s photograph of a table in the Illini Union food court. Food stains can be seen on the lower-left side of the photograph.

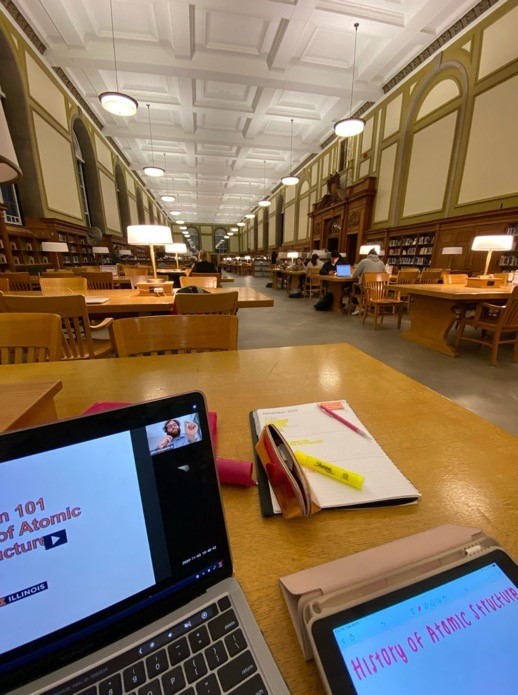

The value of understanding how a space is intended to be used was further demonstrated by a conversation with the fall 2022 participants about the main library reading room featured in Figure 4. Irene commented, ‘I like that this is a dedicated quiet space’. Later on, Victor (a research team member) summarised the discussion stating that, ‘Sense of belonging is related to the space being purpose-built for what you want to do. But also tied to who is in the space’. Jami and Irene agreed with this summary, and Jami added: ‘It’s more about my work, [I] want to be around people with the same energy’. While participants appreciated dedicated spaces such as these, the spring 2023 participants further discussed navigating the expectations of quiet and loud spaces alike for using synchronous meeting software, such as Zoom, as more work has moved online.

Figure 4. Lizbeth set up a learning space at the main library reading room, a quiet study space.

Participants also identified temporary spaces where it appeared the expectation is not to spend a lot of time, but to quickly take care of tasks, or catch up with someone. This included the low, soft furniture in the main library (Figure 5) and certain spaces in the Illini Union. Whether these spaces are intended for short-term use was unclear, but participants agreed that they probably are when looking at the photographs together.

Figure 5. Soft furniture in the main library scholarly commons. Lina stated that these seats are ‘usually available, maybe because they can be a bit uncomfortable to work on at times because they are so low’.

Utility

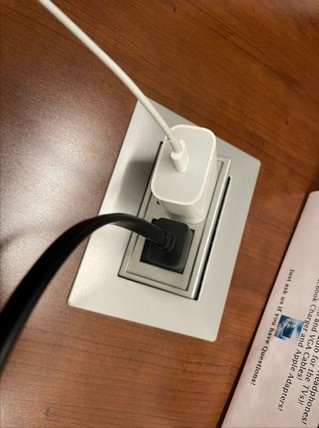

The ability to functionally use or access technology was integral to the utility of third spaces for participants in both fall 2022 and spring 2023. Approximately one in five photographs across both rounds of the study included images of the participants’ laptop or other personal devices, computer station or related technology, such as the tableau of Lizbeth’s study space in Figure 4. Participants in fall 2022 also noted the importance of shared computers, scanners and printers, as well as loanable technology offered by the main library’s scholarly commons, to carry out their work (Figure 6). In particular, Irene commented on the importance of informing students of the existence of such technologies stating that, ‘People don’t know what UIUC offers through the libraries. [It’s] important to have eye-catching posters so people know what’s available’. Beyond the various technologies, the greatest utility commented upon was access to power sources.

Figure 6. Jami’s photograph of available resources for productivity in the scholarly commons of the main library.

In fall 2022, Irene included a picture of a table with an outlet (Figure 7) as she is often studying for hours at a time and noted disappointment when outlets are unavailable. In spring 2023, participants specifically mentioned outlet access more than fifteen times, positively reflecting upon spaces with robust access, and expressing a desire for more outlets in spaces where these were limited. Moreover, while participants in spring 2023 noted how nice it would be to have more outdoor study spaces, the main deterrent was lack of outlets, followed by lack of proper shade and the unregulated temperature of metal furniture in hot and cold temperatures, negating these spaces’ overall functionality for extended work (Figure 8 & Figure 9).

Figure 7. Irene’s photograph of an embedded outlet, a necessary feature for prolonged visits to third spaces.

Figure 8 & Figure 9. Outdoor study spaces captured by Madison. Participants commented upon the lack of outlets and shade solutions, resulting in students moving the tables and chairs in Figure 9 to a more comfortable spot.

Furniture, aesthetics and ambience

Participants photographed and discussed table design and arrangement at length. Large tables seemed to waste space, unless per space expectations there was a way to communicate that it is okay to share with someone. As Lina stated, ‘...even though [the reading room] has large tables, it doesn’t feel like you’re invading someone’s space like at the Union’, with others discussing features such as multiple reading lamps per table and bookshelves serving as important signifiers that this is a place of study. This contrast was demonstrated through photos (Figure 3 and Figure 4) of the awkward lower-level Illini Union tables with the communal tables in the main library reading room. In addition to the tables in the main library reading room, participants also appreciated furniture intended for individual study, such as the carrels at the Funk Library (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Madison’s photograph of an individual-use study carrel at Funk Library, a branch library that supports life sciences disciplines including the College of Agriculture, Consumer, and Environmental Sciences and more.

In conjunction with tables, seating options were featured heavily in the photographs, including chairs that were mentioned either for their comfort, or lack thereof, or for their ability to facilitate long-term study, or short-term visits. As pertains to comfort and accessibility, the participants noted the importance of having options for different types of study and for all body types.

Figure 11. Samyla’s photo of a space with poor lighting and an uncomfortable couch with a tall table directly behind, allowing visual access to seated students’ screens.

Figure 12. Sreelakshmi’s photo of a seated area in the Natural History Building; observed as a space with a great ambience that is ideal for checking emails before class, but not for long-term studying owing to the uncomfortable chairs.

Participants also discussed spaces that were aesthetically pleasing. Individual aesthetic preferences varied between historic spaces with grand visuals and warm lighting and sleek, modern spaces with windows and bright, natural light. Irene stated in fall 2022 of the main library featured in Figures 4 and 13, ‘This space feels like Hogwarts to me and I always tell my friends’, while others observed the traditional, studious ambiance of the space contributed to an excellent environment to conduct school work. Of the Siebel Center for Design, Jami stated, ‘It just feels nice to be there. It’s nice to look at. Really bright environment’ (Figure 14). While some participants enjoyed older buildings, or an abundance of windows, one observed downside to both was how the sun could uncomfortably heat a space. Moreover, some participants appreciated vibrant paint colours on the walls in study spaces, whereas others found features such as the bright orange walls in the Orange Room, or the loudly patterned carpet in the Funk Library distracting.

Figure 13. Library Gallery of the main library with a historic aesthetic, photographed by Lizbeth.

Figure 14. Siebel Center for Design with a modern aesthetic photographed by Jami.

In juxtaposition with the aesthetically pleasing spaces, participants reflected upon spaces that required maintenance, or were visually unwelcoming. Jami noted the ‘worn-down’ and ‘gloomy’ aesthetics of the South entrance to the main library, pointing out elements such as peeling paint and detritus on the floors from the changing seasons, and Sol photographed the overflowing trash receptacles at the entrance to the Grainger Engineering Library Information Center (Figure 15). Beyond spaces showing signs of aesthetic neglect, participants found certain spaces elicited a sensation of unease, in particular, old hallways.

The accessible hallway ramp in the main library that allows patrons to bypass a set of marble steps in the historic building (Figure 16) was noted by Sreelakshmi in spring 2023 to provide a ‘jarring experience’ because of the lack of thought that went into planning the impact this workaround would have on those with mobility devices. Additionally, Madison noted the ‘cracked, stained concrete [and] metal grate’ led her to think, ‘you look down the hallway and go, ‘I don’t want to go down there’’, and Samyla ‘...would rather skip class than have to go down there’. Lastly, of the second-floor hallway of the main library (Figure 17), Sreelaskshmi evocatively stated, ‘This looks like a still out of a horror movie…the chair is low to corner you while the slasher comes down the hall’.

Figure 15. An overflowing trash receptacle at the Grainger Engineering Library entrance photographed by Sol.

Figure 16 & Figure 17. The accessible hallway ramp and the second-floor hallway in the main library photographed by Lina.

Finally, participants wanted a variety of sound levels represented in study spaces and they acknowledged that this is often self-regulated by fellow students. The participants found that there is a difference between an ambient buzz that facilitates studying and sound that is distracting, such as the piano in the Illini Union. In spring 2023, Daniel emphasised the beneficial nature of offering multiple volume levels for study and work within a single building, stating that, ‘it’s comforting to be able to move between quiet and louder spaces’.

Convenience

Participants appreciated having study space options across campus, including locations close to their resident halls or housing, or in buildings they spend a lot of time in for classes, work and leisure. This included new-to-them study spaces discovered through conversations with friends. While convenient locations were appreciated, convenient hours, transportation and available seating were critical for the participants.

Jami noted in fall 2022 that late night hours in more than one location are necessary depending on where one is based on campus, stating that, ‘hours matter’. Similarly, Irene mentioned that she is unable to visit certain library locations owing to lack of nearby bus stops. The availability of seating (especially following closure of the Undergraduate Library and the loss of significant square footage therein) was a particular source of inconvenience, with five of the participants in spring 2023 commenting on the inability to find seating, especially in the main library, at peak hours.

Lastly, the ability to eat and drink (or access food) in spaces where individuals study and work for long periods of time was an important marker of convenience for participants (Figure 18 & Figure 19). Coffee cups or food were featured in a number of the photographs, with participants explicitly requesting options for spaces where they could eat.

Figure 18. Studying in the Illini Union, photographed by Samyla. Note the space is food and drink friendly.

Figure 19. Jami’s friend eating lunch in the Orange Room of the main library. While Jami appreciates a food-friendly space, Jami also emphasised the importance of making microwaves and utensils available to students.

Homeness

Mehta and Cox cite the Oxford English Dictionary definition of homeness as ‘the quality or condition of being homelike’; distinguishing homeness from the domestic pursuit of making a space homelike (2021, p. 29). Like Mehta and Cox, the participants in this study found certain qualities made spaces feel like home and appreciated finding spaces that communicated homeness. This included the community present in a space, the look and feel of a space and thoughtful details within a space.

In Fall 2022 Lizbeth stated, ‘I identify as Latina so to see other students who are similar to me makes me feel welcomed, I feel like a part of home is there’. Irene agreed about the importance of diverse representation in study spaces, stating that, ‘I felt comfortable with the diversity around me’. Sreelakshmi also highlighted the importance of community, stating of the Gender & Sexuality Resource Centre (GSRC) pictured in Figure 20, ‘I am most often at the GSRC when I am on campus, even more so than my desk at my laboratory, because of how welcoming the space is. I see myself and my friends reflected in the images and art on the wall.’

Moreover, Irene stated, ‘There are some buildings that do not look like an academic building. It just looks more like home’. Small touches also made spaces feel like home for participants. Irene noted the cozy Communications Library, ‘They are having coffee and cookies before finals and that makes me feel like I am at home in a little section of a house’ (Figure 21). Similarly, Jami stated of the zine cart in the Orange Room, ‘I like doing creative things…sometimes you don’t want to go to the library to do work. Made me feel like I belong there…’

Figure 20. The Gender & Sexuality Resource Centre photographed by Sreelakshmi.

Figure 21. The Communications Library with cozy touches, such as holiday lights in the top-right corner, photographed by Irene.

By contrast, campus policies that limit access to various spaces made students feel unwelcome by proxy. Irene elaborated, ‘Some buildings communicate that you cannot go into the building if not the correct major’, with other participants agreeing that more access to academic buildings themselves is integral to their comfort and productivity.

Discussion

Signs played a significant role in the discussions we held with the study participants as they described their own interpretations of signs in the library. Signs are more than wayfinding; they send students messages about priorities and values of both the campus and the library. Impromptu signage (see Figure 1) led participants to wonder about the resources available to staff and staff working conditions, while the volume of signage indicating a difficult to locate classroom made students wonder about why this space was so much more important than others. There can be a fundamental disconnect between the intent of those who develop signage and the understanding gleaned by those who read them.

The University Library has developed more consistent and professionally designed wayfinding signage that is currently in use across the main library building and other branch libraries. The Library developed a typology of spaces for different levels of collaboration and noise, resulting in a study space directory for patrons who want to know where they can attend a Zoom meeting or find a silent study space. We are cognizant, however, about the limitations of signage for communicating with library patrons (Polger, 2021). And, perhaps more importantly, we still lack ways to communicate directly about the intangible aspects of a space: who else will they find there? What response will they receive to violating noise expectations? Is the furniture movable in practice, or does the signage requesting that tables and whiteboards be returned to their original configuration tell students they should just use the space as they encounter it? Further research is needed into effective methods for communicating the intangible aspect of spaces to library users.

We can also communicate our values and priorities to our users through more than intentional signage. As our student participants noted, furniture and lighting choices can change the feeling of a space, from ‘studious’ to ‘gloomy.’ We send messages about who is intended to occupy a space, and for what purpose, through means beyond signage and we must continue to consider this fact in our decision-making. A poorly lit hallway with a heavy door may communicate that students are not supposed to be there, even though it may be the only accessible entrance to a particular student-focused space (see Figure 16). It is clear our students (and library users in general) pick up on this or may interpret choices differently than intended. It is likely that libraries will continue to need to be creative with limited funds when it comes to our spaces, but there can still be intent in our choices. It may be tempting to use a hallway or other visible space to store unused furniture. Figure 17 (‘looks like a still out of a horror movie’) shows mismatched furniture moved from the closed Undergraduate Library. What does this communicate to our users? Can they sit there? Is it temporary?

The meaning of flexible spaces

Flexibly designed spaces and movable furniture allow individual patrons the ability to adapt spaces to their needs in the moment and for libraries to change space configurations as campus priorities, technologies and user needs change over the years. This study challenged our assumptions about how students experience library spaces that are designed for flexible use. While flexible use spaces have become increasingly common in academic libraries as a way of acknowledging diverse needs and collaborative pedagogies (Choy & Goh, 2016; Cox, 2023), it appears that this flexibility may sometimes come at the cost of communicating to students about the expectations for a particular space in a way that risks making students feel unwelcome. Instead of allowing students the autonomy to make use of the spaces in ways that fit their needs, the study participants showed concern that they would transgress unstated expectations. This finding challenges us to think more broadly about how we can communicate with users about space expectations, without unduly limiting the types of activities that are permitted and expected within any given space.

Flexible design is a way that universities and libraries can respond to the likelihood of rapid technological and social change, such as we witnessed in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Institutional priorities, however, do not always coincide with the ideal outcomes for individuals. This research challenges our own notions of what it means to be flexible about the use of spaces and the messages we send when we repurpose furniture for a new space, or expect patrons to understand that they can make use of spaces to meet their own needs.

Reflecting on the impact of research practices

Participatory research methods are less common in library research and rarely used in our own library. Given this relative rarity, we also reflect on the use of the photovoice method in particular and the challenges of conducting engaged research in collaboration with students in a way that is meaningful and has the potential to affect change.

Implications for participants

Throughout the process of the student-focused spaces project, we have been cognizant of the potential impact of our research processes on the individuals who volunteered to participate and our ongoing relationships with the campus organisations to which students belong. We are particularly mindful of being at a predominantly white institution where students from marginalised groups are frequently asked to provide feedback and share their (potentially unwelcoming) experiences for the sake of institutional assessment. This situation mirrors the research landscape at large, where the participation of those from marginalised communities is often considered most valuable and authentic when those participants share their stories of pain (Tuck & Yang, 2014).

This project represents a growing interest among our library staff in engaging meaningfully with our patron community, particularly students, as we make changes in library services and spaces. Many library employees have developed relationships with campus organisations that serve students from underrepresented minority communities, but we are hesitant to overburden members of these communities with sharing their, potentially harmful, experiences with library and campus spaces with us so that we can develop reports and plans for our organisation. This concern has been discussed within the Library as part of addressing student-focused spaces and an effort is underway to coordinate efforts across our large organisation to solicit feedback and formal research participation.

We also find ourselves carefully approaching whether to involve students in participatory research, given the slow levers of change that operate within the library and our campus at large. Some of our recommended changes are within the power of the library to implement, such as the addition of a microwave to a student-accessible space. Other changes, such as adding additional single-user restrooms, require extensive resources and the coordination of multiple campus units. Participants who share these needs help us make the argument for these vital updates to our spaces, but those individuals are also unlikely to see the results of their effort in their time at the University.

Implications for researchers

Like students and study participants, we as librarians and staff can also be frustrated when the effort put into collecting and analysing data, writing reports and making suggestions for changes within the library appear to result in little concrete change. This is particularly challenging for questions of space, given the extent of resources and campus coordination required. While we approach the completion of this project with appreciation for the insights shared by participants and a broader understanding of student experiences in library spaces, we also note a sense of deja vu. Given our collective years of experience in academic libraries, we are keenly aware of the limitations of our work and the potential for burnout that comes with seeing needed change bogged down in organisational limitations.

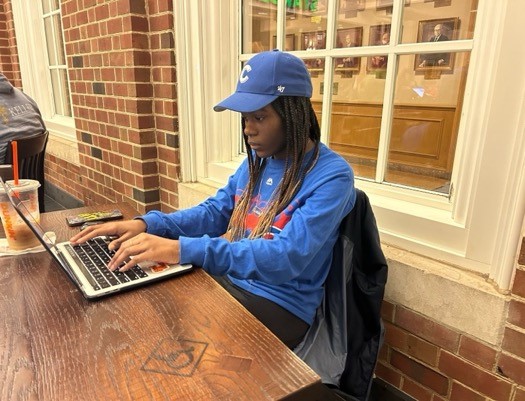

Our mixed positionalities and our personal and professional experiences play an important role when we analyse findings and reflect on what we learned beyond just the findings. Like students, we work in, and pass through, many neglected places seen in Figures 15, 16 and 17. We have also been in spaces that showcase the University history, which is prominently white and male-centred. One can see that behind the window in Figure 18, there are portraits of distinguished alumni. While Daniel captured the photograph below (Figure 22) to show a study space, the first thing we saw in the photograph was the oil painting of a past University president that is four times larger than the sign that shows important services for students (study space, events, Writers Workshop and food pantry). How would students develop a sense of belonging here, if we, as photovoice researchers and librarians and staff, also don’t see ourselves in it?

Figure 22. Daniel’s photograph of an entrance to the Orange Room. We saw the oversized oil painting of a past University president, the cold marble floor and a small sign that says this space offers study spaces, the Writers Workshop and a food pantry.

Conclusion

In a library system as dispersed as ours, it is important that we continue to look more broadly at all library spaces and develop shared understandings of what is available and where, so that this can be clearly communicated to current and potential users. Thoughtful design that includes clear, cohesive signs is needed within library spaces—users should know the intended purpose of a space. For flexible spaces, this may require more than relying on the presence of movable furniture. Our findings support other studies evaluating student needs in study spaces, reiterating the importance of creating functional spaces with the necessary features and providing access to a variety of spaces with different noise levels and furniture types across campus that are safely accessible to students at all hours. Developing a sense of homeness in a library can help signal to students that they are welcome and that they belong there.

Students are extremely perceptive and read more into our spaces and what we put in them than we might anticipate. It is important to think about spaces broadly and holistically. We believe that participatory research methods have strong potential for facilitating this type of change in thinking within libraries and encourage other researchers to consider these methods, although with care to the realistic change participants would observe. While addressing concrete needs will continue to be important, a method that de-centres the researcher and focuses more on the participants will have lasting (although invisible) impact and result in a deeper understanding of users. This leads to better awareness of potential issues and more productive discussions.

Research into library space is often design-focused and conducted in preparation for upcoming projects, or to assess the effectiveness of a previous change. However, researchers have begun to argue for more user-centred, holistic approaches to space assessment (Trembach et al., 2020) and ‘regular studies with repeated cross sectional or longitudinal design’ (Andrews et al., 2016) to better understand the student experience in library spaces. Cox (2023) outlined possible features that will drive change in future use of library spaces post COVID, including student well-being and mental health concerns, sustainability, DEI and decolonisation, co-design with students and new technology. The importance of incorporating student voices throughout the process of evaluating and designing spaces is crucial for academic libraries. There is additional value in ongoing, consistent research, or other engagement with students, for meaningful work that is not performative, but instead has potential for transformative change within both libraries and librarians.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the other photovoice research team member, Victor Jones, Jr., the students that participated in this study, and the rest of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Library’s Student-Focused Spaces Task Force.

About the authors

Kate Lambaria is Associate Professor and Music and Performing Arts Librarian at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Her research interests focus on music reference services and the role libraries play in the preservation and dissemination of performance materials. She can be contacted at lambari1@illinois.edu.

Jessica Hagman is the Social Sciences Research Librarian at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Her research interests include academic library services and instruction for graduate students, particularly in the area of qualitative research data management and analysis. She can be contacted at jhagman@illinois.edu.

Kirsten Feist is the Undergraduate Instruction and Engagement Strategist at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Libraries. Her current research interests include undergraduate library instruction and assessment with a focus on multilingual, international learners. She can be contacted at kmfeist@illinois.edu.

Jen-chien Yu is the Director of Library Assessment at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Jen coordinates library assessment programs and works closely with faculty and staff across the Library, and around the campus, to design and implement assessment activities that support data-informed decision making related to library services, collections, technology, and facilities. Her research interests include library assessment, UX and data analytics and visualization. She can be contacted at jyu@illinois.edu.

References

Andrews, C., Wright, S. E. & Raskin, H. (2016). Library learning spaces: investigating libraries and investing in student feedback. Journal of Library Administration, 56(6), 647–672. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2015.1105556

Beatty, S., Hayden, K. A. & Jeffs, C. (2020). Indigenizing library spaces using Photovoice methodology. In S. Baughman, J. Belanger, E. Durnan, E. Edwards, M. Kyrillidou, K. Maidenberg, A. Pappalardo, & M. Strub (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2020–2021 Library Assessment Conference: building effective, sustainable, practical assessment. Association of Research Libraries. https://www.libraryassessment.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/186-Beatty-Indigenizing-Library-Spaces.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20221011103135/https://www.libraryassessment.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/186-Beatty-Indigenizing-Library-Spaces.pdf)

Bodaghi, N. B. & Zainab, A. N. (2017). My carrel, my second home: inclusion and the sense of belonging among visually impaired students in an academic library. Malaysian Journal of Library & Information Science, 18(1), 39–54. https://mjlis.um.edu.my/index.php/MJLIS/article/view/1835

Bucy, R. (2022). Native American student experiences of the academic library. College & Research Libraries, 83(3). https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.83.3.416

Chapman, J., Daly, E., Forte, A., King, I., Yang, B. W. & Zabala, P. (2020). Understanding the experiences and needs of Black students at Duke (p. 39). Duke University Libraries. https://hdl.handle.net/10161/20753

Chodock, T. (2020). Mapping sense of belonging in library spaces. In S. Baughman, J. Belanger, E. Durnan, E. Edwards, M. Kyrillidou, K. Maidenberg, A. Pappalardo & M. Strub (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2020–2021 Library Assessment Conference: Building Effective, Sustainable, Practical Assessment. Association of Research Libraries. https://www.libraryassessment.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/197-Chodock-Mapping-Sense-of-Belonging.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20221024032622/https://www.libraryassessment.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/197-Chodock-Mapping-Sense-of-Belonging.pdf)

Choy, F. C. & Goh, S. N. (2016). A framework for planning academic library spaces. Library Management 37, 13-28. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-01-2016-0001

Click, A. B. (2014). “Taking something that is not your right”: Egyptian students’ perceptions of academic integrity. Libri, 64(2). https://doi.org/10.1515/libri-2014-0009

Couture, J., Bretón, J., Dommermuth, E., Floersch, N., Ilett, D., Nowak, K., Roberts, L. & Watson, R. (2021). “We’re gonna figure this out”: First-generation students and academic libraries. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 21(1), 127–147. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2021.0009

Cox, A. (2023). Factors shaping future use and design of academic library space. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 29(1), 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2022.2039244

Diller, K. R. & Wallin, S. B. (2023). Place attachment, libraries, and student preferences. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 23(4), 683–715. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2023.a908698

Elteto, S., Jackson, R. M. & Lim, A. (2008). Is the library a “welcoming space”?: an urban academic library and diverse student experiences. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 8(3), 325–337. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.0.0008

Haberl, V. & Wortman, B. (2012). Getting the picture: interviews and photo elicitation at Edmonton Public Library. Library and Information Science Research E-Journal, 22(2). https://doi.org/10.32655/LIBRES.2012.2.1

Julien, H., Given, L. M. & Opryshko, A. (2013). Photovoice: a promising method for studies of individuals’ information practices. Library & Information Science Research, 35(4), 257–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2013.04.004

Keyes, K. (2017). Welcoming spaces: supporting parenting students at the academic library. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 43(4), 319–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2017.06.001

Latz, A. O. (2017). Photovoice research in education and beyond: a practical guide from theory to exhibition. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315724089

Lippincott, J. K. (2022). 21st-Century libraries for students: learning and belonging. In H. T. Hickerson, J. K. Lippincott, & L. Crema (Eds.), Designing Libraries for the 21st Century (pp. 43–52). Association of College and Research Libraries.

Lloyd, A. & Wilkinson, J. (2016). Knowing and learning in everyday spaces (KALiEds): mapping the information landscape of refugee youth learning in everyday spaces. Journal of Information Science, 42(3), 300–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551515621845

Luo, L. (2017). Photovoice: a creative method to engage library user community. Library Hi Tech, 35(1), 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHT-10-2016-0113

McDonald, A. (2006). The Ten Commandments revisited: the qualities of good Library space. LIBER Quarterly: The Journal of the Association of European Research Libraries, 16(2). https://doi.org/10.18352/lq.7840

Mehta, P. & Cox, A. (2021). At home in the academic library? a study of student feelings of “homeness.” New Review of Academic Librarianship, 27(1), 4–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2018.1547774

Neurohr, K. A. & Bailey, L. E. (2016). Using photo-elicitation with Native American students to explore perceptions of the physical library. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 11(2), 56–73. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8D629

Newcomer, N. L., Lindahl, D. & Harriman, S. A. (2016). Picture the music: performing arts library planning with photo elicitation. Music Reference Services Quarterly, 19(1), 18–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/10588167.2015.1130575

Polger, M. A. (2021). Library signage and wayfinding design: communicating effectively with your users. American Library Association.

Poljak, L., Webster, B. M. & Kiner, R. (2023). Exploring belonging through photovoice: examining the impact of space design on diverse student populations in an academic library. Performance Measurement and Metrics, 24(3/4), 195–210. https://doi.org/10.1108/PMM-08-2023-0023

Schultz, T., Anderson, K., Smith, M. M., Mesfin, T., Damonte, H. & Masegian, C. (2023). First generation students’ experiences and perceptions of an academic library’s physical spaces. Weave: Journal of Library User Experience, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.3998/weaveux.1681

Scott, R. & Varner, B. (2020). Exploring the research and library needs of student-parents. College & Research Libraries, 81(4), 598-616. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.81.4.598

University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Student Affairs. (2021). Student Experience Survey: Spring 2021 [PowerPoint slides]. https://hdl.handle.net/2142/123576

Tewell, E. (2019). Reframing reference for marginalized students: a participatory visual study. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 58(3), 162–176. https://doi.org/10.5860/rusq.58.3.7044

Trembach, S., Blodgett, J., Epperson, A. & Floersch, N. (2019). The whys and hows of academic library space assessment: a case study. Library Management, 41(1), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-04-2019-0024

Tuck, E. & Yang, K. W. (2014). Unbecoming claims: pedagogies of refusal in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 20(6), 811–818. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800414530265

University Library. (n.d.). Diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility at the University Library. Retrieved June 18, 2024, from https://www.library.illinois.edu/geninfo/deia/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20240625130808/https://www.library.illinois.edu/geninfo/deia/)

Wang, C. & Burris, M. A. (1994). Empowerment through photo novella: portraits of participation. Health Education Quarterly, 21(2), 171–186.

Copyright

Authors contributing to Information Research agree to publish their articles under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which gives third parties the right to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format. It also gives third parties the right to remix, transform and build upon the material for any purpose, except commercial, on the condition that clear acknowledgment is given to the author(s) of the work, that a link to the license is provided and that it is made clear if changes have been made to the work. This must be done in a reasonable manner, and must not imply that the licensor endorses the use of the work by third parties. The author(s) retain copyright to the work. You can also read more at: https://publicera.kb.se/ir/openaccess

Appendix A: photovoice instructions for participants

Photovoice Instructions for Participants

Dear Participant,

Thank you for agreeing to participate in the Student-Focused Spaces Study (Protocol Number #23471) conducted by the University Library. As a part of this study, you are asked to respond to prompts through photography. Participation in this study will include taking a series of photographs with the camera on your cell phone. Following each photography session, you will upload the photos to Canvas and leave annotations about your photos explaining how they represent the prompt. When submitting your photo to Canvas, you are giving the Research Team permissions to use your photos for the following purposes: research reports, publications, and public presentations. The project may culminate with a public exhibition or creation of zines that will include the research findings and the photographs. Your involvement and/or participation in this portion of the study is encouraged, but it is completely up to you whether or not you participate. Know that your participation in this study is totally voluntary. You may withdraw at any time, and the photographs and data you’ve submitted will be destroyed if you withdraw consent.

The photos you share are intended to represent your personal experiences with spaces in and around campus. We recognize that other people are often important to how you feel about a space, but we encourage you to be sparing in capturing identifiable images of others who are not study participants. You may photograph individuals in public spaces (such as in a public park, on sidewalks) or in private spaces (such as homes, classrooms, vehicles). If you intend to take photos that capture an individual’s image or likeness, you must obtain their consent. Copies of the Photovoice Information Sheet are provided to you. Please ask those to be photographed to sign the sheet and retain the signed copy. A blank copy can be given to the individual. Remember to carry these forms and a pen with you as you engage in photography. Also remember to obtain consent before taking photos of individuals.

Important Points to Remember When Taking Photos:

Keep sunlight to your back when taking photos outdoors.

Use the flash when taking photos indoors or low-light situations.

Feel free to take horizontal and vertical photographs

Be as creative as you like. There are no ‘rules’ per se. You are simply asked to respond to the prompts, in any way you like, through photographs.

You are welcome to crop, collage, or edit photos before sharing them with us to ensure that they communicate your personal experience in the way that feels most authentic to you.

Minor or children under the age of 18 should not be the subjects of your photographs. If you unintentionally included minors or children on your photographs, please blur out their faces before you submit the photographs in Canvas.

You may not take photographs that are pornographic or contain illegal activity.

When taking photographs, do not place yourself in dangerous situations, trespass, or that put you in violation of any university policies or the student code of conduct.

If you are questioned about why you are taking photographs, feel free to distribute the project information sheet. If you need more copies, please contact us.

Be sure to have all necessary forms on hand when you take photos for the project.

If you should have any questions throughout the duration of the research project, please contact [redacted] at any time. I can be reached through email [redacted]. Thank you so much for your willingness to participate!

Appendix B: photo upload in Canvas

Appendix C: photovoice discussion guide

Introduction

“Student-focused spaces” refer to spaces that support student activities including studying, events, workshops and programming, tutoring, wellness, and success services. The goal of this research is to understand the different space needs of college students, and specifically students’ sense of belonging in spaces.

Ground Rules

We want YOU to do the talking

We would like everyone to participate

I may call on you if I haven’t heard from you in a while

There are no right or wrong answers

Every person’s experiences and opinions are important

Speak up whether you agree or disagree

What is said during the focus group stays here

We want everyone to feel comfortable sharing

If you feel uncomfortable, you can discontinue participation and leave the meeting at any time

We will be recording the meeting

We want to capture everything you have tos ay

We won’t identify anyone by name in our reports.

Opening questions

Could you show the group pictures of your favorite places to study at? And why do you like about these places?

Could you show the group pictures of places that you feel welcome?

Could you show the group pictures that represent what you do during a typical day during the semester?