Information Research

Vol. 30 No. 3 2025

Exploring the benefits of leisure reading for medical students and the role of medical libraries in promoting leisure literature: a scoping review

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/ir30354561

Abstract

Introduction. Leisure reading, often called pleasure reading or voluntary reading, refers to reading for enjoyment outside of academic requirements. This study focuses on understanding the benefits of leisure reading specifically for medical students and explores strategies that medical libraries employ to foster these reading habits.

Method. This study uses thematic analysis based on Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-phase framework. This approach found recurring themes across twenty (20) selected studies on impact of leisure reading on medical students.

Analysis. Thematic analysis uncovered five (05) primary themes: fostering empathy in medical education, enhancing critical thinking and reflective skills’, ‘ethical decision-making through narrative reflection’, cultivating cultural competence in healthcare’, ‘promoting stress relief and emotional well-being among medical students.

Results. Analysis of these themes shows that leisure reading provides substantial personal and professional benefits for medical students. This includes the development of critical skills essential to medical practice and the enhancement of emotional and reflective abilities, which medical libraries play a significant role in promoting.

Conclusion. Despite a limited number of studies from 1962 to 2023, findings suggest a need for more comprehensive, longitudinal research to fully understand the impact of leisure reading on medical students. Incorporating leisure reading collections in medical libraries could be vital for the emotional and intellectual growth of future healthcare professionals.

Introduction

The term ‘leisure reading’, often referred to as ‘pleasure reading’ and ‘voluntary reading’, is considered reading for enjoyment and something outside the curriculum. According to Clark and Rambold (2006), ‘reading for pleasure refers to reading that we do of our own free will, anticipating the satisfaction that we will get from the act of reading’. In leisure reading, reading materials are generally selected according to individual preferences without external influences. Leisure reading allows people to engage in reading, which gives them a sense of fulfilment (Clark & Rambold, 2006). Amidst a busy and tiresome academic schedule, a short break for leisure reading can provide many important benefits for medical students (Watson, 2016).

Novels, fiction, short stories, poetry, and drama are commonly available leisure reading materials. These leisure reading materials belong to different genres of literature such as realistic fiction, fantasy, mystery, romance, thriller, horror, adventure, biography, autobiography, true history and historical fiction, philosophy, religion, comedy, tragedy, poetry, personal development, news and folklore.

Different studies worldwide have investigated the benefits of leisure reading for various communities, age groups, and other social categories. This paper aims to understand the benefits of leisure reading for medical students through the available literature. Further, this study explored the initiatives of medical libraries to promote leisure reading based on literature. The study is a scoping review to gather all possible literature relevant to the objectives.

Conceptual background

According to Rosenblatt’s theory (as cited in Damico et al., 2014), reading is an interactive process, and pleasure reading does not merely deal with decoding texts but involves readers’ cognitive and emotional responses. Readers can gain a more whole and meaningful experience when they enjoy the work they read. Damico et al. (2014) further mention that readers’ sociocultural experiences and backgrounds can influence the enjoyment they gain from reading. They further stated that the enjoyment gained through pleasure reading triggers readers to read more complex text forms and helps them get closer to their cultural identities.

Deci and Ryan (1985) formulated a theory called self-determination. This theory suggests that human motivation is controlled or driven by three basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence and relatedness. This theory applies to different phenomena where human cognition is involved. Concerning pleasure reading, ‘autonomy’ can be described as the ‘ability to select whatever reading material preferred by the reader’. When readers have autonomy, their reading texts relates more to their life experiences. ‘Competence’ relevant to pleasure reading can be described as innovative ideas gained, interpretation of texts, and confidence gained while reading. ‘Relatedness’ deals with the similarity between experiences gained through reading and the external environment.

Krashen’s Input Hypothesis (Ponniah & Krashen, 2008) is another foundational theory supporting the voluntary reading concept. According to Krashen’s concept of free voluntary reading, people who read different types of texts out of their personal interest and their own free will tend to gain considerable general knowledge and reading skills, leading to greater understanding. This refers to reading not confined to the borders of formal reading of educational material. Krashen’s framework can be a foundation for understanding the benefits gained by medical students through leisure reading.

Another theory related to leisure reading is the Theory of Mind (Premack & Woodruff, 1978). According to the Theory of Mind (ToM), humans and animals have developed the ability within themselves to understand others’ intentions and thoughts. These thoughts and intentions are not visible outwardly—they are unseen traits. ToM helps people and animals to predict what others do under certain circumstances. According to ToM, when people engage in leisure reading, the reader can identify the minds of different characters in the book. Neuroscience and psychological aspects of leisure reading are linked closely with this theory.

Contextual background

Studies by Mar, Oatley, and Peterson (2009) and Kidd and Castano (2013) have shown that leisure reading improves empathy and social cognition by allowing readers to stimulate the characters that appear in books mentally. These are vital requirements for medical students who should develop empathy, an essential quality in patient care.

Evidence from previous studies on leisure reading related to tertiary education can be found across various study disciplines. Applegate et al. (2014) studied the willingness for leisure reading among students in the second year and above and future teachers in a large public university in the USA. Considering its benefits, the study revealed a need to promote enthusiasm for leisure reading, especially among future educators. Brookbank (2023) reports that promoting a culture of leisure reading in academic institutions can boost students’ personal and academic development. Gallik (1999) explored the relationship between leisure reading habits and academic achievement of university students. He found a significant positive correlation between the time students spend on leisure reading during vacations and the marks they scored. Hurst et al. (2017) examined how the academic success of university students is affected by leisure reading. The findings revealed that students who read leisure material regularly achieved higher academic performance.

Kelly and Kneipp (2009) found that university students who engaged in leisure reading were creative thinkers compared to other students. MacAdam (1995) noted that the honours students in a university strongly preferred to read extra-curricular material for pleasure, and through an analysis, stated that leisure reading has a positive impact on the studies of university students. Martin-Chang et al. (2021) confirmed the positive effects of leisure reading on academic achievements, highlighting the significance of encouraging reading for pleasure among university students. Mahaffy (2009) examined how leisure reading affects academic accomplishment and found that students engaged in leisure reading have better grades. Mol and Bus (2011) explored the impact of exposure to literature on language and cognitive growth through a meta-analysis. They concluded that early and frequent reading involvement positively affects development. Above-mentioned papers collectively show how leisure reading has excreted a positive impact on the academic achievements of university students.

Nathanson, Pruslow and Levitt (2008) surveyed practising and aspiring teachers. They revealed that this group’s personal reading habits positively affected their teaching effectiveness. Salter and Brook (2007) investigated the reading preferences of library and information science professionals. They declared that many were passionate readers, but there was variability in reading frequency and preferences.

While the above-mentioned papers emphasise the importance of promoting leisure reading among university students belong to different study disciplines, this study investigates the effect of leisure reading on medical education.

Research question

What are the benefits of leisure reading for medical students, as reported by literature, and what are the evidence-based strategies medical libraries can implement to promote leisure reading habits among medical students?

Objectives

To identify the benefits of leisure reading for medical students using existing literature.

To explore and summarise practices of medical libraries in promoting leisure reading among medical students.

Methodology

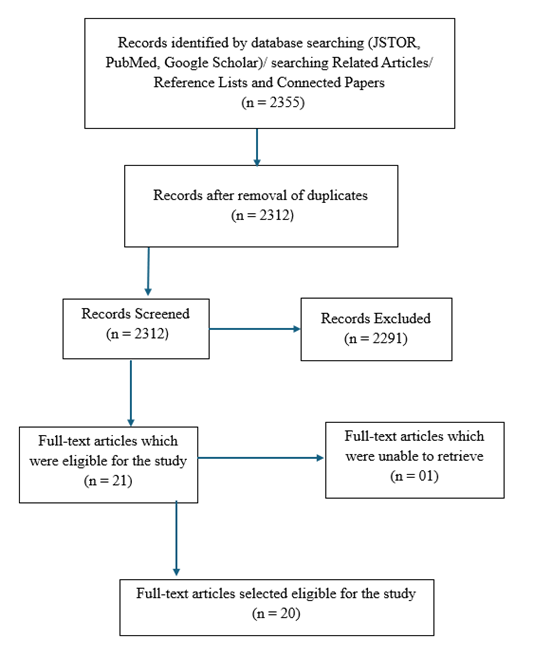

A comprehensive literature search of electronic databases, including PubMed (MEDLINE), Google Scholar and JSTOR was conducted to identify relevant papers. No date limit was used. The Boolean operator OR was used to combine search terms of similar concepts: "pleasure reading", "leisure reading," "fun reading”, “recreational reading”, “free-choice reading”, “voluntary reading”, “personal reading”, “non-academic reading”, “informal reading”, “enjoyment reading’, “casual reading” and “light reading”. The results were combined with Boolean operator AND with the search terms of similar concepts combined with OR; “medical”, “medical student*”, “MBBS”, “MBBS student*”, “healthcare student*”, “medical School*”, “medical college*”, “medical facult*”, “medical librar*”. The links directed to related papers and reference lists were also checked to gather relevant papers. Further, the ‘Connected Papers’ platform was used to retrieve most relevant papers. A total number of 2355 documents were retrieved and were imported to the Zotero reference manager application. Forty-three (43) documents were removed as duplicates. The remaining number of 2312 documents were imported to Rayyan application. A double-blind peer review was conducted by two reviewers. Exclusion criteria were; scholarly papers about pleasure reading relevant to pre-school, elementary school and high school; scholarly papers about pleasure reading relevant to undergraduates who are not attached to medical schools, scholarly papers about curriculum-related reading; scholarly papers related to pleasure reading promotion and initiatives taken by non-medical libraries; scholarly papers written in languages other than English; scholarly papers which the full text content is not available. The inclusion criteria were scholarly papers about pleasure reading relevant to undergraduates attached to medical schools, faculties and colleges: leisure reading initiatives, scholarly papers on leisure reading promotion done by medical libraries; leisure reading initiatives by medical faculties. A majority of 2291 documents were excluded. Another one paper was excluded as the full-text content was not available. Only twenty (20) papers were selected for the review. The papers were reviewed focusing two key aspects relevant to the objectives as: benefits of leisure reading for medical students and evidence-based initiatives taken by medical libraries in pleasure reading among their undergraduate user community. Figure 1 shows the method of selection of sources of evidence according to PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) (Tricco et al.).

Figure 1. Selection of papers based on PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews)

Thematic analysis was used to analyse the data, as mentioned by Braun and Clarke (2006). A total number of 20 scholarly papers were selected. Table 1 shows the complete set of papers selected for the study.

| No | Scholarly paper | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 01 | Literature and medicine: a short course for medical students | Calman (1988) |

| 02 | Why literature and medicine? | McLellan and Jones (1996) |

| 03 | Narrative in medical ethics | Jones (1999) |

| 04 | What do medical students read and why? A survey of medical students in Newcastle upon Tyne, England | Hodgson and Thomson (2000) |

| 05 | What can students learn from studying medicine in literature? | Hampshire and Avery (2001) |

| 06 | What do Italian medical students read? A call for a library of good books on physicians for physicians | Piccoli et al. (2003) |

| 07 | Humanities in a course on loss and grief | Mc Ateer and Murray (2003) |

| 08 | Towards improved collections in medical humanities: fiction in academic health sciences libraries | Dali and Dilevko (2006) |

| 09 | Reading habits and attitude toward medical humanities of basic science students in a medical college in western Nepal. | Shankar et al. (2008) |

| 10 | Literature and psychiatry: the case for a close liaison | Bokey and Walter (2002) |

| 11 | Dickens’ characters on the couch: an example of teaching psychiatry using literature | Douglas (2008) |

| 12 | Using medical fiction to motivate students in public health fields. | Assier (2012) |

| 13 | A literature and medicine special study module run by academics in general practice: two evaluations and the lessons learnt | Jacobson et al. (2004) |

| 14 | Finding time for fiction | Johnson (2015) |

| 15 | The importance of leisure reading to health sciences students: results of a survey | Watson (2016) |

| 16 | Integrated course in psychiatry and literature during preclinical years and medical students' grades in the general psychiatry curriculum | Fan et al. (2010) |

| 17 | Should psychiatrists read fiction? | Beveridge (2003) |

| 18 | Impact of Leisure Reading on stress levels of Medical Students | Viqar (2018) |

| 19 | Reading Literature enhances empathy and decreases stigma in medical students towards patients with depression | Van Oosbree (2023) |

| 20 | A Medico-Biographical Bibliography for Medical Teaching and Leisure Time Reading | Schneck (1962) |

Table 1. Final set of scholarly papers selected for the study.

A total number of five (05) scholarly papers which discuss initiatives taken by medical libraries in promoting pleasure reading were identified. Table 2 shows the complete set of papers selected for the study.

| Scholarly paper | Country | Year |

|---|---|---|

| A Medico-Biographical Bibliography for Medical Teaching and Leisure Time Reading (Schneck, 1962) | USA | 1962 |

| What do Italian medical students read? A call for a library of good books on physicians for physicians (Piccoli et al., 2003) | Italy | 2003 |

| Towards improved collections in medical humanities: fiction in academic health sciences libraries (Dali and Dilevko, 2006) | Canada | 2006 |

| Leisure reading collections in academic health sciences and science libraries: results of visit to seven libraries (Watson, 2014) | Canada | 2013 |

| The importance of leisure reading to health sciences students: results of a survey (Watson, 2016) | Canada | 2016 |

Table 2. Initiatives taken by medical libraries in promoting pleasure reading.

Analysis

According to the guidelines described by Braun and Clarke (2006), a thematic analysis having six (06) phases was conducted for Table 1 as follows.

Step 1- Familiarisation with the data: Each paper was read carefully. Methodologies of the papers were carefully identified. Key findings of each research were noted. Writing the key findings helped to identify recurring themes. As stated by Braun and Clarke (2006), ‘Repeated Reading’ was done to familiarise with papers, search for meanings and patterns.

Step 2- Generating initial codes: The key findings were identified and noted. An initial list of ideas was generated. According to Braun and Clarke (2006), this phase involves production of codes from the available data. According to Boyatzis (1998), as cited by Braun and Clarke (2006), “codes identify a feature of the data (semantic content or latent) that appears interesting to the analyst, and refer to the most basic segment, or element, of the raw data or information that can be assessed in a meaningful way regarding the phenomenon”.

After developing initial codes for Table 1, the results were recorded in Table 3.

| No | Reference | Initial Codes |

| 01 | Schneck (1962) | Lowering stress levels Increase emotional well-being |

| 02 | Calman (1988) | Empathy towards patients Developing critical Thinking Helps to connect with human experiences Helps to maintain humane qualities Helps to be more open-minded Helps to appreciate different perceptions. |

| 03 | McLellan and Jones (1996) | Developing empathy through literary analysis Ethical reflection Incorporation of literature into medical education Merging of aesthetic and ethical approaches in medical education As a tool for enhancing communication and moral reasoning Historical relationship between literature and medicine. |

| 04 | Jones (1999) | Helping to solve Ethical Dilemmas Ethical Dilemmas through stories Influence of narrative on ethical decision-making Autonomy and the patient's role as the author of their story Use of fictional and autobiographical narratives in teaching ethics Narrative as a tool for moral reflection Co-construction of patient-doctor stories Literary criticism in medical ethics |

| 05 | Hodgson and Thomson (2000) | Cultural awareness Decline in leisure reading due to academic pressure Social environment impact on reading habits Limited access to fiction books Tiredness as a barrier to reading Reading for introspection and inspiration Emotional responses evoked by reading Interest in Including medical humanities in the curriculum |

| 06 | Hampshire and Avery (2001) | Understanding patient experiences Awareness of the psychological impact of illness on patients Impact of illness on families and friends Reflection on clinical experiences through literature Changes in attitudes towards patients Greater empathy for patients with mental health issues Literature as a tool for understanding ethical dilemmas |

| 07 | Bokey and Walter (2002) | Literatures’ ability to cure, heal and harm Literature enhances empathy Literature holds information on mental illnesses. |

| 08 | Piccoli et al. (2003) | Cultural enrichment Integration of leisure reading to medical humanities Interest in non-medical books among medical students Preference for novels and short stories High frequency of reading books about physicians and medicine Support for humanities in the medical curriculum Suggestion for a dedicated library section for non-medical books on medicine Balance Between technical and humanistic aspects of medicine Cultural interests as personal choices |

| 09 | Mc Ateer and Murray (2003) | Critical thinking Integration of personal and professional experiences Development of empathy through vicarious experiences Reflection on loss and grief in clinical practice Complementary role of humanities in clinical education Use of literature to understand emotional reactions to loss Improved communication and therapeutic relationships Enhancement of reflective practice through literary analysis |

| 10 | Dali & Dilevko (2006) | Fiction plays a vital role in medical humanities. Fiction offers insights into the human condition. Fiction enhances empathy. Fiction helps to solve ethical dilemmas |

| 11 | Shankar et al. (2008) | Holistic medical education cultural enrichment Attitudes towards medical humanities Preference for romantic fiction and science fiction Decline in reading habits due to academic pressure Interest in medical humanities among students Benefits of leisure reading: Relaxation, enlightenment, understanding others Importance of humanities in developing humane doctors Barriers to introducing humanities: Overcrowded curriculum Need for optional study modules on medical humanities |

| 12 | Douglas (2008) | Literature as a teaching tool for psychiatry Illustration of mental disorders through Dickens’ characters Enhancing empathy in medical students through literary characters Linking historical psychiatry with modern-day mental health education Use of fiction to understand psychiatric diagnoses. |

| 13 | Assier (2012) | Enhanced empathy and ethical awareness Motivation and engagement Critical thinking and problem solving Cultural competence Confidence in oral participation |

| 14 | Jacobson et al. (2004) | Enhanced understanding of illness experiences Personal and professional growth Improved critical thinking Leisure and personal enjoyment Therapeutic and reflective writing Patient-centered care Broadened perspectives Therapeutic value of creative writing |

| 15 | Johnson (2015) | Enhanced clinical understanding Increased empathy Psychodynamic formulation skills Avoiding burnout Improved tolerance for ambiguity Cultural competence |

| 16 | Watson (2016) | Development of empathy Stress relief and relaxation Cultural understanding Enhanced communication skills Broadened perspectives and critical thinking Inspiration and personal growth |

| 17 | Fan et al. (2010) | Improved understanding of psychiatric disorders Increased empathy for psychiatric patients Enhanced critical thinking and reflective skills Reduction of academic stress Greater interest in psychiatry Personal connection with patients through literature Improved long-term retention of knowledge |

| 18 | Beveridge (2003) | Development of empathy Understanding patient narratives Bridging science and the humanities Ethical reflection through fiction Enhanced interpretive skills Exposure to complex psychological conditions Critique of purely scholarly models in psychiatry |

| 19 | Viqar (2018) | Reduction of stress levels Leisure reading as a coping strategy Improvement in relaxation and enjoyment Academic performance balance Barriers to reading (Time Lack of Interest) Diverse reading preferences (Genres) Correlation between reading and lower stress |

| 20 | Van Oosbree (2023) | Decrease in stigma towards depression Improvement in empathy levels Lack of statistically significant increase in kindness Literature as a tool for long-term stigma reduction Greater impact on students without personal experience with MDD Literature’s effect on empathy irrespective of personal experience Limited impact on students with personal experience of MDD |

Table 3. Initial codes developed after reading the papers carefully.

Step 3- Searching for Themes: According to the guidelines described by Braun and Clarke (2006), the third step of the Thematic Analysis is searching for themes or collating codes into potential themes and gathering all data relevant to each potential theme as depicted in Table 3.

| Theme | Codes and References |

|

Having Empathy towards patients: Calman (1988) Fiction plays a vital role in medical humanities: (Dali and Dilevko, 2006) Fiction enhances empathy (Dali and Dilevko, 2006) Enhanced Empathy and Ethical Awareness: Assier (2012) Literature’s Effect on Empathy Irrespective of Personal Experience: Van Oosbree (2023) |

|

Developing Critical Thinking: Calman (1988) Fiction offers insights into the human condition: Dali and Dilevko (2006) |

|

Ethical reflection using literature: McLellan and Jones

(1996) Fiction helps to solve ethical dilemmas: Dali and Dilevko (2006) |

Cultural Enrichment |

Cultural Awareness: Hodgson and Thomson (2000) Cultural enrichment: Piccoli et al. (2003) Cultural Interests as Personal Choices: Piccoli et al. (2003) Holistic Medical Education Cultural Enrichment: Shankar et al. (2008) Cultural Competence: Assier (2012) Cultural Competence: Johnson (2015) Cultural Understanding: Watson (2016) |

|

Reducing stress levels (Schneck, 1962) Enhance emotional well-being (Schneck, 1962) Benefits of Leisure Reading: Relaxation, Enlightenment, Understanding

Others: Shankar et al. (2008) |

Table 4. Themes developed by collating similar codes.

Step 4- Reviewing Themes: The themes were checked for consistency and reviewed. The compatibility of themes with the codes were specifically checked. This ensured that the themes represented a broader spectrum of codes. No themes were removed according to the context of the study.

Step 5 -Defining and naming the themes: After reviewing the themes, clear definitions and names were formulated for each theme considering the benefits gained through leisure reading by the medical undergraduates as follows.

Fostering empathy in medical education

Enhancing critical thinking and reflective skills

Ethical decision-making through narrative reflection

Cultivating cultural competence in healthcare

Promoting stress relief and emotional well-being

Step 6- Producing the report: This step included producing a comprehensive report after generating a fully developed set of themes from the analysis. The report is presented under the Results and Discussion.

Results and discussion

The results and discussion identify all five (05) themes as benefits of leisure reading for medical students and are discussed based on similarities, differences of studies, and potential avenues for future research. Further, the initiatives medical libraries have taken to promote leisure reading among their users are discussed based on the five (05) papers identified.

Fostering empathy in medical education

The scholarly papers studied identified literature as an effective tool to cultivate empathy within a medical student. This scoping review detected multiple studies indicating similar findings showcasing literature as a tool for inculcating empathy in medical students, although they have used different approaches and methodologies.

For example, Calman (1988) and McLellan and Jones (1996) showed that integrating well-organized structured small-group discussions on literature into the curriculum helps medical students to develop their emotional intelligence as they focus on moral and ethical dilemmas.

On the other hand, Hampshire and Avery (2001) highlights the self-initiated reading experiences of students who read illness-related literature and how it triggered empathy in their minds. It is an example of self-directed approach without external inputs. A similar approach for a self-directed reading experience is described by Johnson (2016) which also discusses enhanced empathy.

On the other hand, Hampshire and Avery (2001) highlight the self-initiated reading experiences of students who read illness-related literature and how it triggered empathy in their minds. It is an example of a self-directed approach without external inputs. Johnson (2016) described a similar approach for a self-directed reading experience that discusses enhanced empathy. However, it is unclear which approach is more effective in inculcating empathy in medical students: structured small group discussions or self-directed approach.

Watson (2016) and Van Oosbree (2023) reveal survey findings on the effect of leisure reading developing empathy towards patients. However, neither study has considered controlling factors (confounding variables) such as personal experience for various illnesses and pre-exposure to literature. This makes it difficult to conclude whether the students who are naturally good readers and have read since childhood develop empathy towards patients or whether the novel reading approach they developed after entering the universities has made them more empathetic towards patients. Therefore, future studies must have proper control over confounding variables, enabling us to identify the pure impact of literature on the development of empathy in medical students.

Enhancing critical thinking and reflective skills.

Calman et al. (1988) and Mc Ateer and Murray (2003) have found that introducing literature courses to medical students encourages them to think more deeply about ethical dilemmas related to patient care. Jacobson et al. (2016) have shown that writing reflections on literature improves the analytical skills of medical students. However, Watson (2016) and Fan et al. (2010) have reported that medical students who read fiction voluntarily also develop strong cognitive abilities even without guided reading programmes.

Ethical decision-making through narrative reflection

According to McLellan and Jones (1996) and Jones (1999), fiction narrating ethical dilemmas provide an opportunity for medical students to think more about such difficult scenarios before facing them in reality. Hampshire and Avery (2001) has found that students who engage in reading fiction about patients achieve a broader view on real-life problems of patients and gain more confidence in ethical decision making. However, Beveridge (2003) and Fan et al. (2010) suggest that psychiatry students benefit more from reading literature because mental health care involves complex issues. However, no research has been conducted so far about different types of literature genres that have higher effects on different specialties in the field of medicine or whether a general approach works for all specialties. Hence, this is a potential avenue for future research.

Cultivating cultural competence in healthcare

According to Hodgson and Thomson (2000) and Piccoli et al. (2003), fiction improves students’ awareness of different cultures and makes them more sensitive to various patient needs. However, Shankar et al. (2008) and Watson (2016) have stated that medical students who read on their own learn more to adjust to different cultural settings than those who read only the required specified texts to complete their assignments.

Based on the findings mentioned above, a question arises as to whether medical students gain cultural awareness properly if leisure reading activities are assigned to them in their curriculum or whether they gain cultural awareness by voluntary reading. Future studies must compare these two settings, and the weight of cultural awareness gained.

Promoting stress relief and emotional well-being

Shankar et al. (2008) and Watson (2016) found that medical students who read fiction have lower stress levels than students who do not read fiction. Fan et al. (2010) found that a literature course introduced to medical students has contributed to elevating their emotional intelligence. Viqar et al. (2018) provided evidence of a significant drop in stress levels in medical students regularly engaged in leisure reading.

Nevertheless, literature-based stress relief will be ineffective for all medical students as there are many other stress-relieving modes, such as music, movies, and exercise. More research is necessary to understand the percentage of students who enjoy literature over other stress-relieving modes in the present context.

Initiatives taken by medical libraries in promoting leisure reading

Based on Jerome M. Schneck’s study (1962), medical libraries can play a key role in promoting leisure reading to alleviate stress and enhance emotional well-being among healthcare professionals by maintaining collections that include medical biographies and autobiographies. Medical Libraries can support this initiative by recommending relevant literature, aiding book selection, and making leisure reading materials accessible to students.

According to Piccoli et al. (2003), Medical Libraries can take several initiatives to promote leisure reading among students. One of the main movements is committing a separate section in the library for non-medical books. This section must include literature such as novels, short stories, and non-fiction that touch on the essence of medicine, humanistic themes, medical ethics, patient-physician relationships and broader societal issues related to the medical context. Also, the libraries can organise seminars and interactive sessions to discuss literature. These materials can be promoted through book lists.

Dali and Dilevko (2006) investigates the under-utilisation of fiction in medical collections in academic health sciences libraries. The paper suggests methods for integrating fiction with non-fiction to improve the accessibility. It also proposes using the Literature, Arts, and Medicine Database (LAMD) to assign medical and health-related classification numbers and subject headings to the fiction titles available in a health sciences library. This method facilitates cataloguing and shelving fiction next to related non-fiction, making fiction more accessible to medical students.

According to Watson (2014), medical libraries can promote leisure reading by setting up separately dedicated ‘leisure reading sections’ within the library. These sections can offer students a range of materials such as novels, short stories, and non-fiction, focussing on medical as well as non-medical themes. Libraries can maintain and promote book lists that suit students’ interests, especially those related to medical humanities. Creating comfortable reading spaces with welcoming shelving and facilitating students’ book clubs can further encourage a culture of leisure reading.

A survey regarding the leisure reading habits of healthcare students conducted in a Canadian University analysed 213 responses from students from different fields, such as medicine, nursing, pharmacy and public health. Most students preferred print over digital leisure reading material. The respondents identified lack of time and fatigue as major barriers to leisure reading. They expressed willingness to support setting up a leisure reading collection within the health sciences library (Watson, 2016).

It is debatable whether medical libraries should promote leisure reading or make the leisure reading collection available exclusively for interested students. Future studies must investigate this argument to determine whether medical libraries should dedicate their resources and time to promote leisure reading.

Conclusion and research gaps

This scoping review shows that leisure reading benefits medical students in five (05) constructive ways: (1) improving empathy, (2) critical thinking, (3) ethical decision-making, (4) cultural competence, and (5) stress management.

According to these findings, leisure reading is not an extra-curricular activity. It can be a strategic tool in medical education to improve medical students’ professional, emotional and thinking skills. These findings align with the expectations of medical humanities, which aim to build a well-rounded medical professional by equally developing knowledge and emotional competencies.

Today’s world observes the reality of a conflicting nature or the paradox of the scientific way of handling things and the medical profession with humane feelings. Worldwide, there is an increased concern about whether the medical profession is heading towards an inhumane nature. This scoping review emphasises that leisure reading or literature, can act as a bridge between the scientific rigour and the emotional intelligence of medical students. Literature helps medical students capture the humane side of clinical interventions by providing a more comprehensive picture of patient suffering.

Some medical schools have included the field of medical humanities in their curriculum. Under medical humanities, some medical schools have allowed students to follow literary courses, but not as compulsory activities (Hampshire and Avery, 2001; McLellan and Jones, 1996). Through this scoping review, we could not find information on the standardisation of literary courses and initiatives to monitor the effectiveness of such courses. Some medical educators who support the traditional curriculum argue that integrating such literary courses into medical school curricula is difficult as they are already overloaded with rigorous activities (Beveridge, 2003; Fan et al., 2010). These traditional medical educators argue that medical humanities courses are considered soft skills.

The gaps identified from the study:

Further research is necessary to determine whether leisure reading increases empathy or whether naturally empathetic students simply enjoy reading.

It is unclear whether assigned literature courses are more suitable for medical students rather than voluntary reading.

Future research should investigate the types of literature genres suitable for different medical specialities.

Although some students may find leisure reading as a mode of stress relief, other students might enjoy different activities and hobbies to relieve their stress. Hence, studies should identify other stress-relieving methods.

The impact of social media and other digital distractions on the leisure reading habits of medical students is largely unexplored.

This study could only find the impact of short-term literary courses on medical students rather than the long-term impact of such courses. This is a significant gap that future research should address.

No studies have provided evidence on the effect of leisure reading on medical students’ clinical decision-making and how they communicate with patients in real-world scenarios. This is a significant research gap for future investigations.

According to the findings of this scoping review, there is limited evidence for medical libraries promoting leisure reading among their users. Medical libraries have taken a few initiatives, but these isolated efforts lack institutional backing.

Medical educators and medical libraries can make better decisions on leisure reading initiatives in medical schools by addressing these gaps. The medical library staff are obliged to collaborate with faculty members, especially with specialists in medical humanities, and research on the medical students’ reading habits. This scoping review provides clear evidence to prove that medical libraries have the potential to promote leisure reading among their users, but such efforts are untouched.

About the authors

K.K.N.L.Perera, Medical Library, Faculty of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

D.C.J.Liyanage, Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

C.Weeraratne, Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

D.C.Kuruppu, Medical Library, Faculty of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

References

Applegate, A. J., Applegate, M. D., Mercantini, M. A., McGeehan, C. M., Cobb, J. B., DeBoy, J. R., Modla, V. B., & Lewinski, K. E. (2014). The Peter Effect revisited: Reading habits and attitudes of college students. Literacy Research and Instruction, 53(3), 188–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388071.2014.898719

Assier, M. L. (2012). Using medical fiction to motivate students in public health fields. ESP Across Cultures, 10, 21-34. https://edipuglia.it/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/ESP-10.pdf#page=22

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Macmillan. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1997-08589-000

Beveridge, A. (2003). Should psychiatrists read fiction? The British Journal of Psychiatry, 182(5), 385-387. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/the-british-journal-of-psychiatry/article/should-psychiatrists-read-fiction/C45BF91E79DEBB3E70F5F41702E2CA6C

Bokey, K., & Walter, G. (2002). Literature and psychiatry: The case for a close liaison. Australasian Psychiatry, 10(4), 393-399. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1440-1665.2002.00502.x

Brookbank, E. (2023). “It makes you feel like more of a person:” The leisure reading habits of university students in the US and UK and how academic libraries can support them. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 30(3), 53–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2023.2261918

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1191/1478088706QP063OA?casa_token=hSCCTYE0PTUAAAAA:elG-DdhXeHYK6AVa_69Oy3BuXBT6x8lHc3T_pv1aITWeoo6ujvJFtCaSbG9WVIn7zjLaHbzrdGxyOs0

Calman, K. C., Downie, R. S., Duthie, M., & Sweeney, B. (1988). Literature and medicine: A short course for medical students. Medical Education, 22(4), 265-269. https://asmepublications.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2923.1988.tb00752.x

Clark, C., & Rumbold, K. (2006). Reading for pleasure: A research overview. National Literacy Trust. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED496343

Dali, K., & Dilevko, J. (2006). Toward improved collections in medical humanities: fiction in academic health sciences libraries. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 32(3), 259-273. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0099133306000462

Damico, J. S., Campano, G., & Harste, J. C. (2014). Transactional theory and critical theory in reading comprehension. In S. E. Israel, S. E. Israel and G. G. Duffy (Eds.), Handbook of research on reading comprehension (pp. 201-212). Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315759609-19/transactional-theory-critical-theory-reading-comprehension-james-damico-gerald-campano-jerome-harste

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Springer Science & Business Media. https://mh.bmj.com/content/34/2/64.short

Douglas, B. C. (2008). Dickens’ characters on the couch: An example of teaching psychiatry using literature. Medical Humanities, 34(2), 64-69. https://mh.bmj.com/content/34/2/64.short

Fan, A. P. C., Kosik, R. O., Su, T. P., Tsai, T. C., Syu, W. J., Chen, C. H., & Lee, C. H. (2010). Integrated course in psychiatry and literature during preclinical years and medical students' grades in the general psychiatry curriculum. The Psychiatrist, 34(11), 475-479. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/the-psychiatrist/article/integrated-course-in-psychiatry-and-literature-during-preclinical-years-and-medical-students-grades-in-the-general-psychiatry-curriculum/910909228A8F79C78BD7037AAF588ED0

Gallik, J. D. (1999). Do they read for pleasure? Recreational reading habits of college students. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 42(6), 480–488.

Hampshire, A. J., & Avery, A. J. (2001). What can students learn from studying medicine in literature? Medical Education, 35(7), 687-690. https://asmepublications.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00969.x

Hodgson, K., & Thomson, R. (2000). What do medical students read and why? A survey of medical students in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England. Medical Education, 34(8), 622-629. https://asmepublications.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00542.x

Hurst, S., Wallace, R., & Nixon, S. (2017). The impact of leisure reading on academic success in higher education. Journal of College Reading and Learning, 47(2), 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790195.2017.1285808

Jacobson, L., Grant, A., Hood, K., Lewis, W., Robling, M., Prout, H., & Cunningham, A. M. (2004). A literature and medicine special study module run by academics in general practice: Two evaluations and the lessons learnt. Medical Humanities, 30(2), 98-100. https://mh.bmj.com/content/30/2/98.short

Johnson, J. M. (2015). Finding time for fiction. Academic Psychiatry, 39(6), 713-715. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40596-015-0341-x

Jones, A. H. (1999). Narrative in medical ethics. BMJ, 318(7178), 253-256. https://www.bmj.com/content/318/7178/253.short

Kidd, D. C., & Castano, E. (2013). Reading literary fiction improves theory of mind. Science, 342(6156), 377–380. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1239918

Kelly, G. E., & Kneipp, L. B. (2009). Reading for pleasure and creativity among college students. College Student Journal, 43(4), 1137–1144.

MacAdam, B. (1995). The reading habits of honors students. Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council, 1(1), 35–41.

Mahaffy, J. (2009). The influence of pleasure reading on academic success. The Reading Matrix, 9(1), 56–66.

Martin-Chang, S., Kozak, S., & Rossi, M. (2021). Effects of pleasure reading on academic success: A replication study. Educational Psychology, 41(5), 631–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2020.1860120

Mar, R. A., Oatley, K., & Peterson, J. B. (2009). Exploring the link between reading fiction and empathy: Ruling out individual differences and examining outcomes. Communications, 34(4), 407–428. https://doi.org/10.1515/COMM.2009.025

Mc Ateer, M. F., & Murray, R. (2003). The humanities in a course on loss and grief. Physiotherapy, 89(2), 97-103. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0031940605605809?casa_token=qLD332sXUzQAAAAA:cRmwsgaSNC1H0q5GghfVETj9QoTeINPb-EthT6aHZR-yVPEcJtPyXJ3gRxrWQ_wk0Wv8Si2uC_j1

McLellan, M. F., & Jones, A. H. (1996). Why literature and medicine? The Lancet, 348(9020), 109-111. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(96)03521-0/abstract

Mol, S. E., & Bus, A. G. (2011). To read or not to read: A meta-analysis of print exposure from infancy to early adulthood. Psychological Bulletin, 137(2), 267–296. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021890

Nathanson, S., Pruslow, J., & Levitt, R. (2008). The reading habits and literacy attitudes of inservice and prospective teachers: Results of a questionnaire survey. Journal of Teacher Education, 59(4), 313–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487108321685

Piccoli, G. B., Mezza, E., Soragna, G., Burdese, M., Bermond, F., Grassi, G., ... & Segoloni, G. P. (2003). What do Italian medical students read? A call for a library of good books on physicians for physicians. Medical Humanities, 29(1), 54-56. https://mh.bmj.com/content/29/1/54.short

Ponniah, R. J., & Krashen, S. (2008). The expanded output hypothesis. The International Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 4(2), 2-3. https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/4385024/The_expanded_output_hypothesis-libre.pdf?1390837012=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DThe_expanded_output_hypothesis.pdf&Expires=1739511991&Signature=HjxBU~Y6hTJOEktuya28HdsevUOXbg65C~~RjElY5R7Lc7xRKCWIr9SH1~r4lz5N1y~5nvXnAByqYrZjGBb~OvCfPOn~CjOLBZw7W1EgW2NRK0A0MwdEu13nwBFPYA8t5VtntHt7c0H7EOS095ijqUJkZCNG1fvNA9FSLM740HV8gWndmONPbJCzEcP366kMfO-biKng-dWUbzBI-zJhLxO460AOp~5xTU-BG1OajDjLraI9wml2V0~xQrvXhnQybnH8qcz61Z4PFEPe7Eh2~LBrTN49DAN~EMn-4ojCCp9XNWwRIHy4bacAGnn1NiMHSXIhXVWIg7v89L82N7R1RA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA

Premack, D., & Woodruff, G. (1978). Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1(4), 515–526. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00076512

Rosenblatt, L. M. (1994). The reader, the text, the poem: The transactional theory of the literary work. SIU Press.

Salter, A., & Brook, J. (2007). Are librarians avid readers? Investigating the reading habits of LIS professionals. Library Review, 56(8), 678–684. https://doi.org/10.1108/00242530710817954

Schneck, J. M. (1962). A medico-biographical bibliography for medical teaching and leisure time reading. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association, 50(1), 30. https://europepmc.org/backend/ptpmcrender.fcgi?accid=PMC199902&blobtype=pdf

Shankar, P. R., Dubey, A. K., Mishra, P., & Upadhyay, D. K. (2008). Reading habits and attitude toward medical humanities of basic science students in a medical college in Western Nepal. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 20(4), 308-313. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10401330802384599?casa_token=xj8WTixl2jwAAAAA:o72U-BMOKKXzihHXV9QNitXKvMvmasIWC6emBVl0ANgKOlTlkk4_n8k_ARmqBU_Qre8Zaqziy-kVksc

Tarulli, L. (2014). Pleasure reading: exploring a new definition. Reference and User Services Quarterly, 53(4), 296-299. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/refuseserq.53.4.296.pdf?casa_token=pX_3IM1TDeMAAAAA:HtZKwmmVmtG1u4x-6w_PNGjf1ObfgTNr1RLnX--BWfaYkJM9YE4CwZr3bJef7Xoy4zlTsxi0YBFcniUt6z7tq2TyFHMZUfCAf6o1RHkbx2OIwAi0mEQ6gA

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., . . . Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467-473. https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/full/10.7326/M18-0850

Van Oosbree, A. (2023). Reading literature enhances empathy and decreases stigma in medical students towards patients with depression. South Dakota Medicine: The Journal of the South Dakota State Medical Association, 76(9), 410-410. https://europepmc.org/article/med/37738494

Viqar, S., Bakhtyar, M., & Farooq, N. (2018). Impact of leisure reading on the stress levels in medical students. Journal of Rawalpindi Medical College, 22. https://openurl.ebsco.com/EPDB%3Agcd%3A11%3A29809067/detailv2?sid=ebsco%3Aplink%3Ascholar&id=ebsco%3Agcd%3A134979095&crl=c

Watson, E. M. (2014). Leisure reading collections in academic health sciences and science libraries: results of visits to seven libraries. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 31(1), 20-31. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/hir.12042

Watson, E. M. (2016). The importance of leisure reading to health sciences students: Results of a survey. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 33(1), 33-48. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/hir.12129

Copyright

Authors contributing to Information Research agree to publish their articles under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which gives third parties the right to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format. It also gives third parties the right to remix, transform and build upon the material for any purpose, except commercial, on the condition that clear acknowledgment is given to the author(s) of the work, that a link to the license is provided and that it is made clear if changes have been made to the work. This must be done in a reasonable manner, and must not imply that the licensor endorses the use of the work by third parties. The author(s) retain copyright to the work. You can also read more at: https://publicera.kb.se/ir/openaccess