Information Research

Vol. 30 No. 3 2025

Activism for the Maya Territory of Yucatán on Facebook: A content analysis

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/ir30358191

Abstract

Introduction. Indigenous activism in digital spaces is becoming increasingly common. This study aims to analyse the activism of Mayan people of the Yucatan Peninsula, expressed in five Facebook pages: Indignación, Colectivo Maya de los Chenes, Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jó, Múuch’ Xíinbal, and Kanan, all managed from the Yucatán Peninsula.

Method. A content analysis was conducted on all posts from these five pages during the year 2023.

Analysis. Descriptive statistics were used for the analysis. A social network analysis was also applied to represent the connections between the pages and their sources.

Results. The results revealed that when the pages rely on information from civil associations, they tend to be more critical of the business sector, such as issues related to macro-farms, bees, or genetically modified maize. In contrast, when the primary source is the press, the pages are more critical of the State, with more focus on the Maya Train. On the other hand, the Maya Train is the most frequently discussed topic. However, other issues, such as macro-farms, bees, and maize, become more viral.

Conclusions. The results demonstrate that there is a clear association between specific topics and sources, and although these pages aim to highlight certain issues, they do not receive as much support.

Introduction

Around the world, Indigenous peoples share specific concerns that are consistent with their worldviews. For example, the defence of territory and its natural resources (forests, flora, fauna, minerals, water, etc.) has been a constant claim of Indigenous peoples, in response to the lack of protection and expropriation they have suffered since colonial times. In this regard, Debo Armenta (2020, p. 110) notes that for them, ‘the territory and the elements that compose it (mountains, forests, rivers, caves, etc.) are essential for the development of their culture, subsistence, and continuity.’

Indigenous claims are based on their worldviews and ways of life, shaped by their cultures, traditions, and beliefs, where nature holds a privileged place. However, they are also a response to the constant encroachment upon their territories, from historical colonisation to the neoliberal boom that has perpetuated and exacerbated the plundering of their lands. The loss of rights, territories, and autonomy leading to habitat degradation has driven Indigenous groups to activism both on the streets and online (Díaz and Sánchez, 2002).

For instance, in Mexico alone, there are currently over 300 disputes between Indigenous peoples and the State. These disputes are generally related to territory, according to the report Indigenous Conflicts in Mexico, prepared by the National Commission for Dialogue with Indigenous Peoples (Debo Armenta, 2020). According to the Special Rapporteur of the United Nations (United Nations, 2018), the main causes of these conflicts are tourism, real estate, and energy megaprojects, among others. The report states that in Mexico, ‘all these problems are developing in a context of deep inequality, poverty, and discrimination against Indigenous peoples that limits their access to justice, education, health, and other basic services’ (United Nations, 2018, p. 1).

This is linked to development policies that benefit powerful economic groups while harming Indigenous communities, a situation not confined to Mexico. According to the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC, 2014), these development ideas have led to socio-environmental conflicts in Indigenous territories.

According to Ávila (2015), in thirty years of neoliberalism, Mexico has promoted numerous megaprojects to attract private and foreign investment, at the expense of expropriating and exploiting the natural resources of territories inhabited by Indigenous communities. Among these resources, water is one of the most contested. Vedana (2004) states that while water is considered a sacred element for life by Indigenous peoples, it is viewed as a commodity by businesses. This cultural clash is at the root of the conflicts and struggles between Indigenous peoples, the State, and the rest of society.

Digital Indigenous activism

The objective of this article is to analyse the activism of Mayan

people of the Yucatan Peninsula, expressed in five Facebook pages. We

assume that Indigenous activism on social media, as with street-based

activism, is primarily focused on the defence of their

territories, crops, flora, and fauna, which are part of the

shared struggles of most Indigenous peoples in the World, and that this

necessarily involves criticism of the State and market.

Celigueta Comerma and Martínez Mauri (2020) assert that despite the growing use of social networks for activist purposes among Indigenous groups, academia has not paid much attention to this phenomenon. Thus, this study aims to contribute to understanding Indigenous activism on social networks, specifically Facebook, the most widely used platform in Mexico (Statista, 2024).

To defend their rights, Indigenous movements employ various actions such as demonstrations or marches, blockades, sit-ins, and the creation of civil organisations, assemblies, or even the promotion of symbolic trials, legal protections, lawsuits, etc. Additionally, this activism is increasingly present in the virtual space (Melucci, 2001; Gómez Mont, 2012; Debo Armenta, 2020).

Firstly, social media activism is often safer. For example, each year there are hundreds of lawsuits for police violence at Indigenous protests, which are avoided when the protest is virtual. Moreover, the virtual space allows activists to share ideas and stay in touch more easily with others who are addressing similar issues. Thus, activist groups inhabit the virtual environment to conduct their struggles with greater reach, visibility, and security. Furthermore, the concept of the digital Indigenous person breaks the stereotype that Indigenous groups are disconnected from technology and are isolated within their localities and communities.

According to Pacheco-Campos (2022), digital activism generally aims to address some social, political, or cultural issue and ‘in the case of digital Indigenous activism, it seeks to promote, encourage, rescue, or defend Indigenous cultures, their knowledge, worldviews, languages, among others’ (p. 97). In this regard, Millaleo and Velasco (2013) propose four types or categories of digital activism: meta-activism, empowerment activism, window activism, and guerrilla activism. In their study, the authors find a predominance of window activism, which refers to a specific group with very particular objectives that seek to share their ideas through specific platforms, with posts focusing more on written content than on visual elements and aimed at more local rather than international audiences.

Debo Armenta (2020) explains that digital Indigenous activism ‘allows certain freedom to express oneself both outside and inside (offline/online) the internet through various resources and tools, such as social networks, websites, and applications’ (p. 117). This aims to raise awareness about issues and encourage mobilisation among others. The author adds that ‘the success or failure of digital collective actions will depend on the technological infrastructure, strategies, and uses conceived from the Indigenous worldview’ (p. 117).

Studying Indigenous activism on social media is quite important as it allows to understand the process of social movements. Firstly, digital platforms, particularly Facebook, provide Indigenous communities with a key tool to make their struggles and demands visible in a global context, without relying on traditional media, considering that its voices have often been stigmatized, marginalized or distorted. These platforms facilitate direct communication between peers and other social actors, enabling Indigenous communities to articulate their claims effectively.

Furthermore, the use of Facebook by these communities offers an opportunity to analyse how they adapt and employ digital technologies to serve their own interests, strategies of resistance, and redeem cultural reproduction, while remaining true to their traditional values and worldviews. This phenomenon invites to reflect on the relationship between digitalisation and self-determination of Indigenous peoples. Also, it highlights the opportunities that technologies create to strengthen their political and social protagonism visible.

On the other hand, studying this type of activism also allows to explore the challenges and risks inherent in the use of digital platforms. While Facebook provides a space for expression and mobilisation, it also exposes communities to dynamics of polarisation and digital control, so it demands a critical analysis of the tensions between freedom of expression and control mechanisms in the virtual environment.

Methods

A mixed-methods approach was employed that encompassed the categorization of textual units into forms of measurement and the interpretation of the meanings of texts deemed relevant. We adhered to Krippendorff's (2018) approach to Quantitative and Qualitative Content Analysis, as he regards both as indispensable. Additionally, to examine the social relevance of the main topics on Facebook pages, we utilized Social Network Analysis to identify the flow of information from the source to the page.

We selected five Facebook pages to analyse. The analysis began with two pages: Indignación and Colectivo Maya de los Chenes. The review of these pages led to others with interesting content to analyse. Thus, the sample was expanded to five pages, which, while interconnected, each had their own intentions and content. A review of more pages allows for a broader view of Indigenous activism in Yucatan.

The inclusion criteria for the pages were: 1) they must contain activism content related to the Maya people, 2) they must be managed from the Yucatán Peninsula, and 3) they must have more than 2,000 followers and interactions (also known as likes). This was to ensure that only the pages with the most followers and interactions were included. The exclusion criteria were: 1) the page should not focus or specialise in a specific issue (language, specific rights, etc.), but rather address multiple topics, and 2) it should not be a political organisation or media outlet, but rather a page managed by civil society groups, without promoting content from specific media or political parties. Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the analysed pages:

| Facebook page name | Number of followers | Introduction of the page | Type of grouping | Date of creation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Indignación |

8,4K likes 9,1K followers |

Indignación promotes and defends human rights in the Yucatán peninsula from an integral, multicultural and gender perspective. | NGO | 6 February 2010 |

Colectivo Maya de los Chenes |

6,1K likes 7,3K followers |

Struggle in defence of Mayan territory | Society and culture | 9 August 2018 |

Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo' |

2,3K likes 2,6K followers |

Group with the objective of informing and articulating ourselves to support the dissemination of information and struggles in Jo' (Merida), Yucatan and the Peninsula. | Cause | 13 November 2017 |

Kanan |

2K likes 2,8K followers |

We are a Civil Association dedicated to activism, accompaniment and defence of human rights. | NGO | 17 January 2020 |

Múuch’ Xíinbal |

12K likes 13K followers |

Defenders of the Mayan territory ‘Múuch’ Xíinbal’. | Community service | 26 February 2018 |

Table 1. Analysed pages.

Actors behind the networks

Regarding the organisations behind these pages, two of them are clearly comprised of individuals who identify as Maya. These are Múuch’ Xíinbal and the Colectivo Maya de los Chenes. Both have a presence in the Peninsula, in rural contexts, and are linked with the National Indigenous Congress, which is a national independent space for communication, reflection, and solidarity of the Indigenous peoples of Mexico.

Múuch’ Xíinbal identifies as an assembly made up of various Maya communities that has been working for decades to defend their territory, combating dispossession, invasion, and destruction affecting the Maya people of the Peninsula. This assembly has an intense communicative presence through Wixsite, Facebook, and YouTube. It operates an internet radio with a repository of podcasts and significant audiovisual production on YouTube (Múuch’ Xíinbal, 2024).

The Colectivo Maya de los Chenes has less intense communication activity, limited to posts on Facebook and Instagram. This collective began its activities over a decade ago, because of the deforestation of over 200,000 hectares of jungle for the planting of genetically modified soy, which has since caused massive die-offs of pollinators. This collective is primarily composed of ‘the ladies of the honey,’ with its leader, Lay Araceli Pech Martín, being awarded the Goldman Prize in 2020 for her environmental advocacy (Mexican Centre for Environmental Law, 2024).

The Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo’ was organised in solidarity with the Zapatista movement and Indigenous groups across the country. It is a network of both Maya and non-Maya allies, recognising Mérida (Jo’) as an urban context. This network has a virtual presence on WordPress, X, and Facebook, as well as radio and video production. It shows significant contact with the Enlace Zapatista, the National Indigenous Congress, and Múuch’ Xíinbal (Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo´, 2024).

In contrast to the previous organisations, Kanan and Indignación are civil associations in form, meaning they have full legal personality, allowing them to not only communicate and report but also engage in legal defence processes within the frameworks proposed by the State. Both organisations are committed to Human Rights. Kanan Derechos Humanos is part of Front-Line Defenders and is made up of a group of young people who began their work in 2020 for the ‘transformation of structures of inequality through a comprehensive and intersectional approach.’ Kanan has a presence on X, Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok (Kanan Derechos Humanos, 2024).

Indignación is a long-established civil association (since 1991) comprising a transdisciplinary team that works from an integral, multicultural, and gender perspective, advocating for causes such as LGBTIQ+ rights, gender equality, freedom of expression, the rights of the Maya people, the elimination of torture, and forced displacement. It is active on Facebook, X, Instagram, and Vimeo. It also publishes the magazine El Varejón periodically and has produced a significant number of reports, books, and documents related to gender, as well as the history, territory, and rights of the Maya people (Indignación, 2024).

Analysis strategies

To understand the activism of those groups in social network, we explore the Facebook pages in a wide form to identify the main topics of discourse. We included most of the posts from each page, excluding those that contained only greetings, farewells, congratulations, condolences, or similar messages. Additionally, posts with commercial objectives (selling products or services) and those that only presented links, where the content was not visible without accessing an external link to Facebook, were excluded. For example, links to podcasts that did not provide specific content but merely connected to another site to listen to the podcast were not included in the analysis. As it was unclear whether page followers interacted with the final content of the links (e.g., whether they listened to the podcast), such posts were not included in the analysis. Based on a computer-assisted content analysis, we identified eight main topics to be coded (Table 2). The tendence and meaning of those posts are analysed and presented as examples in a qualitatively manner.

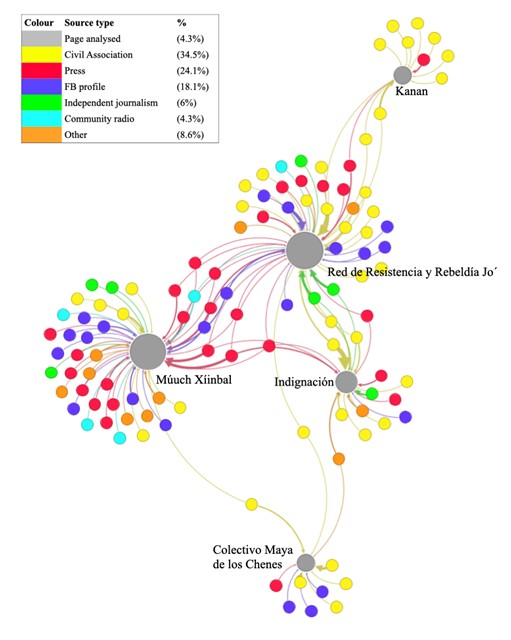

After doing so, a Social Network Analysis methodology was also used to observe the flow of information received by the pages from their sources (Facebook profiles, media outlets, civil organisations, etc.). The network is presented as a graph, with nodes (pages and sources) and edges (connections between nodes). A directed network was analysed due to the asymmetric flow of information (from the source to the page). It was also an egocentric network, as the study focused on analysing the environment of the five Facebook pages; sociocentric networks aim to visualise the overall structure of the network without specific emphasis (Requena Santos, 1989; Lakon et al., 2008).

A total of 116 nodes (sources) and 213 edges (connections) were obtained. Structural measures considered were average in-degree (information reception), average out-degree (information emission), network diameter (maximum distance between nodes), connected components (connection to the global network), and modularity (connection to subgroups).

Instrument and study variables

The research instrument was a content analysis guide, applied to the 396 analysed posts. The guide organised the data into three axes: 1) Record, 2) Topics of the posts, and 3) Characteristics of the posts, as shown in Table 2. The data were manually extracted from Facebook into an Excel database, for subsequent qualitative and quantitative analysis. A descriptive statistical analysis of all posts was first conducted, followed by a more in-depth analysis of the most recurring contents.

| Block data | Variables | Codes and categories obtained |

|---|---|---|

| Registration | Registration number | Free text |

| Page name | Free text | |

| Date of publication | Month and year | |

| Number of likes | Number | |

| Number of comments | Number | |

| Number of shared | Number | |

| Headline | Free text | |

| Remarks | Free text | |

| Topics | Defence of the territory | Yes or no |

| Maya Train | Yes or no | |

| Violence | Yes or no | |

| Water | Yes or no | |

| Macro pig farms | Yes or no | |

| Situation of bees | Yes or no | |

| Maize cultivation | Yes or no | |

| Mayan language | Yes or no | |

| Features | Original author | Name |

| Type of authorship | Press, association, user, etc. | |

| Type of locality | Rural or urban | |

| Place name | Free text |

Table 2. List of variables, codes and categories of the study.

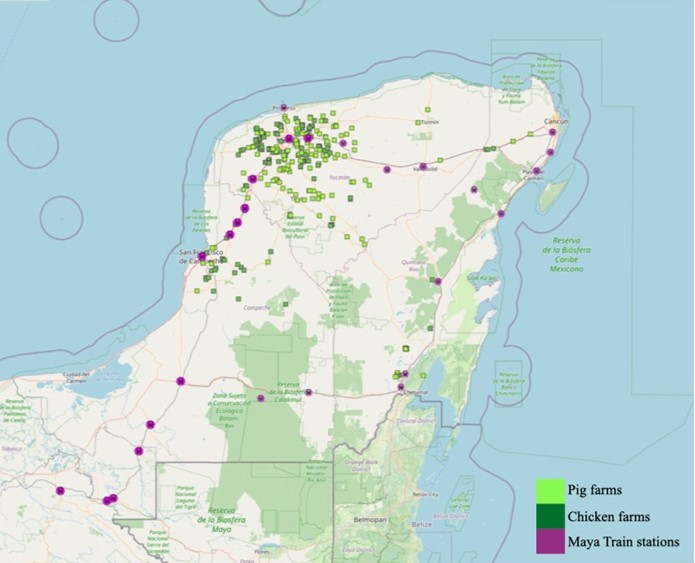

For the qualitative component, we applied thematic analysis to each post to code and analyse them within their thematic framework. We had some predefined themes, such as the Maya Train and macro pig farms, but during the coding process, additional themes were incorporated as they emerged. Figure 1 presents several macro-projects in the region, including pig farms (depicted in light green), chicken farms (shown in dark green), and the current and projected Mayan Train stations (shown in violet).

Figure 1. Map of macro-farms and the Mayan train in Yucatán (Geocomunes, 2025).

Results

The results are organised according to the study's indicators. It begins with the distribution of posts by pages, dates, and topics. A brief characterisation follows the most recurrent topics, with examples of their posts. Later, an analysis of the authorship of the posts and their interactions is presented. At the end, there is the Social Network Analysis for the information sources of the analysed pages.

General characteristics

During the study period, the pages that published the most were: Múuch’ Xíinbal (40%) and the Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo´ (22%), followed by Indignación (14%), Kanan (13%), and Colectivo Maya de los Chenes (11%).

Topics

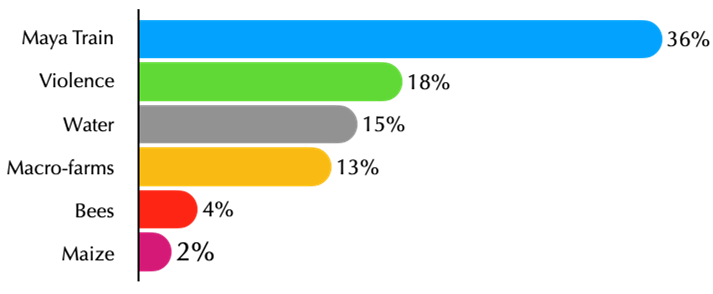

The most recurrent topic was the Maya Train, followed by violence, water, macro-farms, the care of bees, and maize cultivation. The indicator for defending the territory is not counted separately, as most posts were related to it. The percentage distribution by topic can be seen in Figure 2. Furthermore, most posts referred to issues in rural areas (77%), very few referred to urban areas (9%), while others did not specify any particular area (14%).

Figure 2. Percentage distribution of main topics of posts

Characterisation of the most recurrent topics

1. Maya train

The most recurrent topic is the Maya Train. Here, news about the impact of the works on Maya territories, as well as the flora and fauna of the region, is commonly shared. For example: ‘Maya Train: 3.4 million trees have been felled or removed’ (Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo´, 2023) or ‘Destruction of cenotes and caves’ (Múuch’ Xíinbal, 2023). This also includes questioning the development model it proposes: ‘It is not progress or development, it is ecocide!!!’ (Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo´, 2023).

The interrelation of this topic with political propaganda and criticism can be seen in some posts such as: ‘Lies as a political project of the 4T. The false inauguration of the so-called Maya train’ (Múuch’ Xíinbal, 2023), or ‘The fourth betrayal’ (Múuch’ Xíinbal, 2023), which are generally opinions or chronicles of opposition journalists published in media and shared by these pages. The most recurrent media sources were: Diario de Yucatán (seven), Aristegui Noticias, Disidente Mx, and Haz Ruido (five each), and El Universal (four).

Furthermore, ideas from Maya cosmovision are shared to interpret what is happening with the Maya Train project in their territories: ‘Maya thought is not against nature but contributes to it,’ or ‘The jungle is Maya life,’ or ‘The milpa resists. The train is not Maya’ (Múuch’ Xíinbal, 2023). Initiatives of resistance by civil organisations against the train's works are also shared: ‘Megaprojects and resistances, urgent reflections from the territories’ (Múuch’ Xíinbal, 2023).

Additionally, information related to the Maya Train that does not directly concern the impact on Indigenous territories but serves to discredit the train's works are shared: ‘Here, the #testimony of a #worker who #describes the #accidents that have occurred during the piling of #poles in the Maya Train’ (Múuch’ Xíinbal, 2023) or ‘Maya Train will cost at least 130% more than expected’ (Múuch’ Xíinbal, 2023).

It is interesting that a news item about the international court ruling against Mexico for committing ecocide and ethnocide due to the construction of the Maya Train was shared on Múuch Xíinbal’s page at least four times on the same day, but taken from different sources such as Forbes, Aristegui Noticias, Proceso, and El Universal.

2. Violence

Violence appears in 18% of the total posts reviewed. It is a transversal topic. Here, actions of violence by security forces, such as the National Guard or state police, against protesters, environmental defenders, and others are usually denounced. Some examples include: ‘Stop the dispossession and police violence in the Maya community of Ixil’ (Kanan, 2023) and ‘Stop the aggression in #Sitilpech!’ (Colectivo Maya de los Chenes, 2023).

This can occur in Yucatán or elsewhere: ‘Eviction of farmers blocking works of the Transisthmian train in Oaxaca’ (Múuch’ Xíinbal, 2023). It is not only the police held responsible for violence: ‘Families and Communities demand the presentation of Ricardo Lagunes and Antonio Díaz, accusing institutions and the mining company Ternium’ (Múuch’ Xíinbal, 2023). The aggression and murders of journalists are also denounced, as Mexico has the highest rates in the world: ‘The truth is not killed by killing journalists!’ (Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo´, 2023).

3. Water

Water is present in 15% of the posts. Most of them defend the right to water. Thus, there is a dissemination of its importance: ‘Water. Cycles, sources, hurricanes, socio-economic and health impacts’ (Múuch’ Xíinbal, 2023). There is also a denunciation of the contamination affecting the aquifers of the Peninsula, especially due to megaprojects (pig farms and the Maya Train). One post states ‘Contamination ‘is much worse than we thought,’ said members of Kanan Ts’ono’ot, Guardians of the Cenotes’ (Indignación, 2023).

Other examples of such posts include: ‘The #macro-farms of #pigs contaminate the #water of #cenotes and threaten health and life’ (Indignación, 2023); or ‘The route of the so-called Maya train is cutting the Chak estuary, breaking the body of water that connects the lagoon of Bacalar, the Río Hondo, and the Bahía de Chetumal’ (Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo´, 2023).

Water is also defended as a fundamental resource for the identity of Indigenous peoples: ‘Water and wells are part of our heritage and give rise to our name and identity as a people’ (Colectivo Maya de los Chenes, 2023). Another post related to identity and maize: ‘Reading and a reflection on narratives about the topic of water prepared by the children of Chunhuhub, Maya community of Quintana Roo, to strengthen their identity as children of maize’ (Múuch’ Xíinbal, 2023).

4. Macro-farms

Other important group of posts is about macro-farms for pigs in the state of Yucatán. Here, the impact of these projects is debated, including waste management, excessive water consumption, contamination of cenotes, etc. Compared to the Maya Train topic, macro-farms correspond to a struggle that has been ongoing for a longer time, as seen in the following post: ‘Activist groups have been advocating these struggles since 2017: ‘Commemorating six years of fighting for cenotes’ (Indignación, 2023).

The hashtag #sitilpech stands out, where there is a conflict between the government, businesses, and the inhabitants of that village due to the impact of a pig macro-farm on their locality: ‘As Mayas from Chuunt’aan, we stand in solidarity with the Maya people of Sitilpech’ (Indignación, 2023). There is also a political denunciation: ‘We demand Mauricio Vila explain how he guaranteed (or did he?) the right of the #MayaPeople to decide #PigsNo Government of the State of Yucatán’ (Indignación, 2023).

This topic has also led to mobilisations: ‘We join the mega-march in solidarity with our brothers from #Sitilpech in defending #Water and #Life’ (Colectivo Maya de los Chenes, 2023). These mobilisations have ended in police violence, according to several posts such as: ‘Criminalising the protest of Maya peoples against pig farms in Yucatán’ (Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo´, 2023). In these struggles, solidarity and identification with others are apparent: ‘#Sitilpech is alive. Sitilpech is all of us. Thanks for so much solidarity #outsideKeken’ (Kanan, 2023).

This topic, along with the Maya Train, has featured in discussions about the problems of megaprojects in Indigenous territories. These include: ‘Yucatán, the train, and the pigs in the International Decade of Indigenous Languages (2022-2023)’ (Múuch’ Xíinbal, 2023) or ‘Megaprojects and resistances, urgent reflections from the territories’ (Múuch’ Xíinbal, 2023). These struggles are framed in a broader context of advocacy that includes not only nature protection but also autonomy and the right to self-determination: ‘#Homún, its defence of the water and land against the invasion of pigs, is a struggle for the right of the people to decide on their future’ (Colectivo Maya de los Chenes, 2023).

5. Bees

This section reflects the situation of bees in the Yucatán Peninsula, which is impacted using pesticides and other toxins employed in mass agriculture, affecting the life of the most important pollinator, the bee. One post summarises the situation as follows:

The Maya community of Suc-Tuc has suffered a massive death of bees due to the irrational use of highly dangerous pesticides. The result of these harmful practices was the death of over 4,000 hives, which perished while performing their pollinating work. The Yucatán Peninsula has suffered severe damage in apiculture due to agroindustry, deforestation, water pollution, land use changes, and genetically modified crops (Colectivo Maya de los Chenes, 2023).

These types of posts give a voice to those directly involved in honey production: ‘Beekeepers express their concern about the current situation of bees in their territory’ (Colectivo Maya de los Chenes, 2023). They also share spaces for debates on the issue: ‘Intergenerational dialogues: Is there a future without bees?’ (Colectivo Maya de los Chenes, 2023). As with many topics, this one is related to others: ‘Yucatán apiculture threatened by the presence of farms in the territory’ (Colectivo Maya de los Chenes, 2023).

Lastly, the defence of bees has led to street demonstrations and criticism of the government's inaction, as seen in this post: ‘HISTORIC MARCH FOR THE DEFENCE OF BEES IN HOPELCHÉN. Our Maya communities in the municipality of Hopelchén peacefully protested against government inaction to protect the lives of bees and the local inhabitants’ (Colectivo Maya de los Chenes, 2023).

6. Maize

These posts highlight the recovery of traditional maize uses by the Maya people: ‘We are excited to invite you to the National Maize Day Conversatory, where milperas and milperos will discuss various community processes related to the defence of their maize seeds’ (Colectivo Maya de los Chenes, 2023). As with bees, there is also denunciation of agroindustry's impact on maize crops: ‘The extensive agroindustry present in the municipality of Hopelchén has caused multiple damages and consequences to the environment’ (Colectivo Maya de los Chenes, 2023).

Maize cultivation is closely related to Maya cosmology, as reflected in this post: ‘Nal is maize cob, it is also Maya community, it is Yuumtsil’s word that teaches us to live in communion, like grains of maize harmonised in a basal which is our community’ (Múuch’ Xíinbal, 2023).

Some posts link the issue to climate change: ‘Rising temperatures. Losses of vegetation and impacts on milpa’ (Múuch’ Xíinbal, 2023), leading to advocacy for ecological agriculture, local products, and environmentally friendly production, as in the following post:

Maya farmers and producers met after months of experimenting with improved maize varieties provided by the team from the National Institute of Forest, Agricultural and Livestock Research (INIFAP) Uxmal branch, led by Dr. Alejandro Cano González. The activity took place in the traditional milpa of Mrs. Maricela Kauil from the community of San Antonio Yaxché. This space shared the experience of working with the improved maize seed, named Sac-beh, a seed derived from the crossing and hybridisation of native varieties with characteristics of the peninsular region (Colectivo Maya de los Chenes, 2023).

7. Other interesting topics

Here we group other topics that are not directly related to Maya issues but appear among their posts. One is the case of Palestine, which has been covered since before the current war. One such post reads: ‘Land and freedom for Palestine’ (Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo´, 2023), addressing the alleged colonisation and genocide by the State of Israel from the Zapatista slogan of land and freedom. The disappearance of the 43 Ayotzinapa students is also present: ‘Nine years of impunity #AyotzinapaSomosTodos’ (Indignación, 2023).

Lastly, it is interesting to note the defence of radio listening: ‘We are very happy because other comrades from Radio 'Lo conseguí soñando' will broadcast some of our content as 'La No-Radio Múuch' Xíimbal'. Let’s listen to the Radio!’ (Múuch’ Xíinbal, 2023). There are also posts commemorating significant dates, such as the abolition of slavery: ‘Today, August 23, we commemorate the International Day of Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition’ (Kanan, 2023).

Authorship and sources of posts

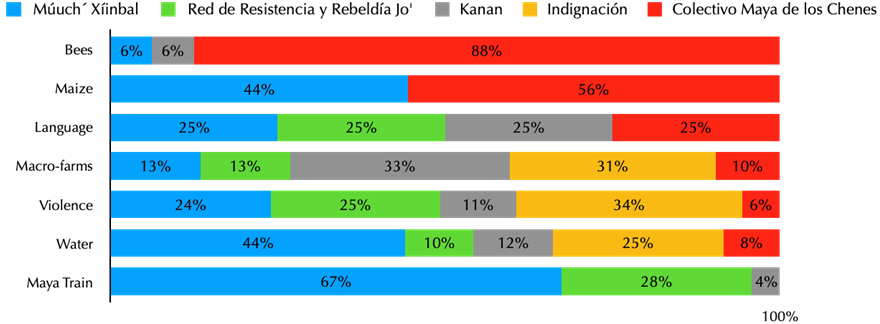

A cross-analysis of the topics and pages shows that posts about the Maya Train are mainly concentrated on two pages: Múuch’ Xíinbal (67%) and Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo´ (28%). Almost half of all posts about water are on Múuch’ Xíinbal (44%). Violence is more present in Indignación (34%), Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo´ (25%), and Múuch’ Xíinbal (24%). Macro-farms are more frequent in Kanan (33%) and Indignación (29%). The situation of bees appears almost exclusively on Colectivo Maya de los Chenes (88%), and posts about maize are distributed between Colectivo Maya de los Chenes (56%) and Múuch’ Xíinbal (44%). However, language appears almost equally across pages: Colectivo Maya de los Chenes (25%), Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo´ (25%), Kanan (25%), Múuch’ Xíinbal (25%), except in Indignación (0%), as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Percentage distribution of the most contrasting topics across the five pages.

A total of 202 posts (52%) were shared from other pages or profiles, whether from Facebook or other social networks or websites. The primary sources in this case were: civil associations (37%), the press (28%), and Facebook profiles (17%). Independent journalism pages (8%), community radios (3%), and other sources, each contributing less than 1%, such as academic organizations, newsletters, cultural centres, specialised magazines, and theatre company pages, were also found.

Civil associations are the most common sources of information on four of the five analysed pages: Kanan (80%), Colectivo Maya de los Chenes (72%), Indignación (48%), and Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo´ (35%). In the latter, Facebook profiles (27%) and the press (23%) are also significant sources. Conversely, on Múuch’ Xíinbal, the most frequent source is the press (41%).

Additionally, over 70% of press releases are shared by Múuch’ Xíinbal and Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo´. Among these, over 40% are about the Maya Train, establishing a connection between Múuch’ Xíinbal and Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo´, with the press as the primary source of information and Maya Train as the main topic. It is important to note that, unlike other topics, the Maya Train was a federal government project promoted by the president and executed by the military in coordination with private capital. In this regard, the final interlocutor these groups address is the state, and due to the lack of official information on the project, and the press has been the most important source of documentation and denunciation.

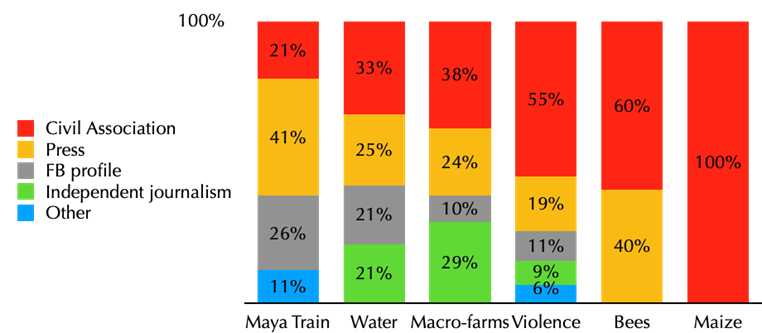

In other topics, the main conflict actors are, on one side, national and transnational companies, and on the other side, the inhabitants of the peninsula. The press has been present in following the conflicts, but civil associations have been more interested in documenting the processes. Thus, these associations have been the main sources for documenting topics such as maize (100%), bees (60%), and macro-farms (38%). The same applies to the topic of violence (55%). In contrast, the press is the primary source only in the case of Maya Train (41%), as shown in Figure 4. It is interesting to observe how academia or various government agencies are not serving as significant sources for these Facebook posts, which leads us to question the role these entities are playing in the production, dissemination, and circulation of relevant information for civil groups and organisations.

Figure 4. Relationship between sources and topics.

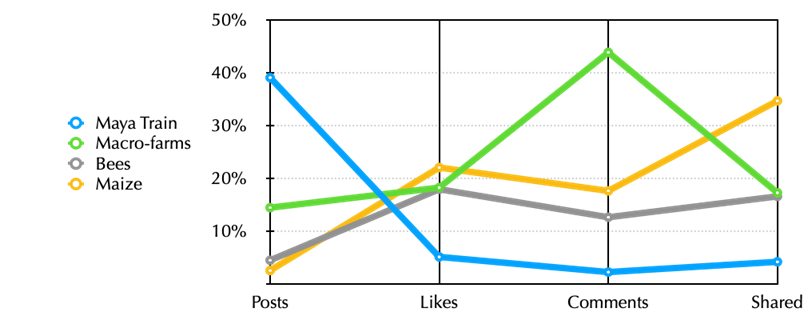

Interactions

Upon analysing interactions (likes, comments, and shares), it appears that although the Maya Train is the most frequently discussed topic on the pages, it does not generate the highest user engagement. As shown in Figure 5, Maya Train accounts for 47% of the total posts, but only 6% of these receive a like, 3% are commented on, and 5% are shared. In contrast, topics such as maize, macro-farms, and bees, despite being less frequently posted, generate higher levels of interaction.

Figure 5. Percentage distribution of posts and their interactions for selected topics.

Social network analysis

The Social Network Analysis revealed that the pages with the highest average number of inbound connections (information reception) are Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo´ (with fifty sources) and Múuch Xíinbal (with forty-seven sources), followed by Indignación (with nineteen sources). In other words, these were the pages that shared the most content from others. On the other hand, the pages with the highest average degree of outbound connections (information dissemination) were Diario de Yucatán, La Jornada, and Proyecto Libres, each sending content to three of the five analysed pages. This indicates that their content reached more pages.

The analysed network had a diameter of one, meaning there is a single step between the two most distant points in the network, which confirms the close interconnectedness of all nodes. The analysis of connected components was one, indicating that all nodes are interconnected with no isolated islands. Of the 116 nodes, only one was weakly connected; the rest were strongly interconnected.

However, the analysis also showed a modularity of 55%. This indicates that the five communities are clearly defined, corresponding to the five analysed pages. These data demonstrate that each page has its own sources while also being part of the same virtual ecosystem, as illustrated in the graph in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Graph of the interconnection of analysed pages by source type.

In this graph, we can observe how the five analysed pages (in grey) are nourished with information from various sources. The three most central pages are: Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo´, Múuch Xíinbal, and then Indignación. The more peripheral pages are Colectivo Maya de los Chenes and Kanan. Kanan is the most isolated as it only shares sources with Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo´; it is also the youngest organisation (it began its work in 2020). Colectivo Maya de los Chenes does not appear as central but shares sources with several pages. The fact that these pages rarely share information with each other indicates a low level of influence between them.

Regarding the most common types of sources for each page, Kanan primarily draws from civil associations (in yellow), which is the opposite of Múuch’ Xíinbal. Conversely, the press (in red) generally feeds two pages: Múuch Xíinbal and Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo´. The press is the predominant source for both, and several of them connect with both pages. Additionally, Múuch’ Xíinbal absorbs nearly all the community radio content (in light blue). Information from Facebook profiles (in purple) appear in almost all pages except Kanan, with a stronger connection to the two pages with the most sources (Múuch Xíinbal and Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo´). This reinforces their connection with other social media activists.

The edges (connections) colour the lines linking the source and the recipient. By examining the lines between Múuch’ Xíinbal and Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo´, it is evident that they are predominantly red, demonstrating that the press was the primary source for these two pages. Moreover, the thickness of the edge indicates the volume of information sent from the source to the page. It is noticeable that Indignación, Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo´, and Colectivo Maya de los Chenes have a civil association from which they draw more than the others. Also, the greater thickness of the edges from some press nodes to Múuch Xíinbal indicates that these are recurring sources, as is the case with Indignación, though to a lesser extent. The same observation applies to the edge from a Facebook profile to Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo´.

Discussion

The struggles of activism in favour of the Maya territory in Yucatán align with those of other Indigenous peoples in Mexico and around the world, as found in some studies (Debo Armenta, 2020; Ávila, 2015). A notable aspect is the defence of territories against megaprojects, whether initiated by the state or private initiatives, as well as the preservation of water, maize cultivation, and bees. This activism is focused on rural issues where most Indigenous peoples reside. It is also noteworthy that there is little content published about the Maya language or other Indigenous languages, despite being a primary objective of digital Indigenous activism according to other studies (Llanes, 2016; Pacheco-Campos, 2022). However, it should be considered that Maya language activism has its own space and network of relationships not described in this research; it operates within a different network.

According to the classification by Millaleo and Velasco (2013), the analysed pages exhibit an ‘activism-window,’ which generally pursues very specific objectives (megaprojects, bees, maize, etc.) through platforms like Facebook. Thus, they form an ecosystem of struggle and resistance, not only concerning issues that directly affect them but also other social groups. For instance, support is shown for external struggles ranging from the missing students in Mexico to the alleged genocide in Palestine, among others. Consequently, it becomes a predominantly political activism (Llanes, 2016), in addition to being ethnic and cultural. As Dávalos (2005) states, Indigenous movements enrich political debate by introducing new issues that are, in fact, old demands reintroduced into the public arena.

In Maya activism in Yucatán, political critique is evident, directed at the federal government regarding the Maya Train project and at local government and the business sector concerning macro-farms. Conversely, there is a scarcity of posts on classism, racism, or even feminism, which are fundamental issues underlying the inequalities faced by Indigenous peoples. This might suggest that the activism is focused on specific objectives rather than structural issues. However, struggles related to water defence or opposition to megaprojects are framed within a much broader claim for autonomy and self-determination as a people, to decide how to utilise their territorial resources and relate to nature (Díaz and Sánchez, 2002).

The Maya Train issue stands out compared to other topics (primarily in contrast with macro-farms, maize, and bees) because, despite being the most frequently published topic, it shows lower public interaction (in likes, comments, and shares). This indicates that the issue is prominent on the digital activism agenda more due to the interests of the pages rather than their followers. In other words, the pages are keen on highlighting the topic in their agendas.

The Maya Train is also the topic where political critique is most evident. To validate the information shared, they rely on the press. For example, the same news about Maya Train is shared four times on the same day from four different media outlets (Forbes, Aristegui Noticias, Proceso, and El Universal). This approach underscores the idea that the news is more legitimate if covered by multiple media sources. This over-representation in the media, combined with the scarcity of official information on the project, or the lack of interest in sharing it, highlights the situation.

The fact that information about the Maya Train predominantly comes from media sources, this raises questions about whether the press is against it while the Maya people support the project? Or does it imply that Indigenous peoples cannot generate their own ideas? This reflection deviates from those ideas. It is observed that these pages might turn to the press for specific issues that align with their own interests, as seen with the Maya Train.

In contrast, for other issues of concern such as macro-farms, maize cultivation, bee protection, or even the preservation and promotion of the Maya language, there is less media support, as these topics are not of high interest to the press but are important to civil associations, as shown by this study. Indeed, the fact that some pages rely primarily on civil associations while others depend on the press explains the content each share. These links between topics and sources help understand the role of sources in Indigenous digital activism.

Considering the sociology of absences, it is striking that two significant sources are missing: official information from various state sectors and academic information. What could be attributed to these absences? Is the information produced by these entities not relevant? Is there a belief that these sectors cannot act as key players in solving the issues? Or is the information produced not suited to the needs of platforms like Facebook?

Conclusions

Among the posts from the five analysed pages, the prominent themes include the defence of territory against the Maya Train project and macro-farms, as well as the protection of bees and maize cultivation. The pages feature political critique directed at the federal government regarding the Maya Train and at the local government concerning macro-farms. Acts of violence against Indigenous peoples and other social groups, especially those defending nature, are also denounced.

Additionally, other social issues such as Ayotzinapa and Palestine are highlighted, and the promotion of community radio as a widely accessible communication medium in rural and Indigenous areas is evident. In contrast, there are few posts advocating for the Maya language or other Indigenous languages, and there is a notable absence of content addressing anti-racism, anti-misogyny, or anti-classism.

The main sources of information were civil associations, the press, and other Facebook profiles. There is a clear association between specific topics and sources: information about the Maya Train primarily comes from the press and other Facebook profiles, while topics such as macro-farms, bees, and maize are mainly sourced from civil associations. While the Maya Train is among the most discussed topics, it generates the least user engagement across likes, comments, or shares.

Acknowledgements

The study on which the paper was based was supported by the Secretariat of Science, Humanities, Technology and Innovation, grant number 784757.

About the authors

Julio C. Aguila Sánchez is a postdoctoral researcher at the Faculty of Anthropological Sciences of the Autonomous University of Yucatan, Mexico. He researches health communication during the pandemic. Email: julio.aguila@virtual.uady.mx

Carmen Castillo Rocha is a professor and researcher at the Faculty of Anthropological Sciences of the Autonomous University of Yucatan, Mexico. She researches communication for social change. Email: ccastillo@correo.uady.mx

Rocío L. Cortés Campos is the director of the Faculty of Anthropological Sciences of the Autonomous University of Yucatan, Mexico. She conducts research on virtual social networks. Email: rocio.cortes@correo.uady.mx

References

Ávila García, P. (2016). Hacia una ecología política del agua en Latinoamérica. [Towards a political ecology of water in Latin America]. Revista de Estudios sociales, 55(1), 18-31. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=81543788004

Celigueta Comerma G., & Martínez Mauri M. (2020). ¿Textiles mediáticos? Investigar sobre activismo indígena en Panamá, Guatemala y el espacio Web 2.0. [Media textiles? Researching Indigenous activism in Panama, Guatemala and the Web 2.0 space]. Revista Española de Antropología Americana, 50, 241-252. https://doi.org/10.5209/reaa.70367

Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (2014). Panorama social de América Latina 2014, (LC/G.2635-P). [Social Panorama of Latin America 2014, (LC/G.2635-P)]. (Technical report). CEPAL. https://repositorio.cepal.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/a31e1273-8437-4e66-a31a-cb3c284fc16e/content (Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20250724064621/https://repositorio.cepal.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/a31e1273-8437-4e66-a31a-cb3c284fc16e/content)

Dávalos, P. (2005). Movimientos indígenas en América Latina: el derecho a la palabra. [Indigenous movements in Latin America: the right to speak out]. In Dávalos (Ed.), Pueblos indígenas, Estado y democracia [Indigenous peoples, state and democracy] (pp. 17-33). CLACSO. https://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/clacso/gt/20101026124338/2Davalos.pdf (Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20250729220535/https://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/clacso/gt/20101026124338/2Davalos.pdf)

Debo Armenta, D. A. (2021). Activismo digital indígena por la defensa del agua: Revisión de casos en Facebook. [Indigenous digital activism in defence of water: A review of cases on Facebook]. Argumentos. Estudios críticos De La Sociedad, 1(95), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.24275/uamxoc-dcsh/argumentos/202195-05

Díaz Polanco, H., & Sánchez, C. (2002). México diverso: El debate por la autonomía. [Diverse Mexico: the autonomy debate]. Siglo XXI.

Geocomunes (2025). Map of macro-farms and the Mayan train in Yucatán. https://geocomunes.org/Visualizadores/PeninsulaYucatan/ (Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20250720021839/http://geocomunes.org/Visualizadores/PeninsulaYucatan/)

Gómez Mont, C. (2005). Tejiendo hilos de comunicación: Los usos sociales de internet en los pueblos indígenas de México. [Weaving threads of communication: the social uses of the internet among Indigenous peoples in Mexico]. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico.

Indignación. (2024). Promoción y defensa de los derechos humanos en Yucatán. [Promotion and defence of human rights in Yucatan]. https://indignacion.org.mx (Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20250712234152/https://indignacion.org.mx/)

Kanan Derechos Humanos. (2024). Página web de Kanan Derechos Humanos. [Kanan Derechos Humanos website]. https://linktr.ee/kanan.ddhh

Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content analysis. An introduction to its methodology. Sage Publications.

Lakon, C. M., Godette, D. C., & Hipp, J. R. (2008). Network-based approaches for measuring social capital. In I. Kawachi, S. V. Subramanian, & D. Kim (Eds.), Social Capital and Health (pp. 63-81). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-71311-3_4

Llanes, G. (2016). Apropiarse de las redes para fortalecer la palabra: Una introducción al activismo digital de lenguas indígenas en América Latina. [Appropriating Networks to Strengthen the Word: An Introduction to Indigenous Language Digital Activism in Latin America]. Research report for Rising Voices (Activismo Lenguas). (Technical report). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323226483_Apropiarse_de_las_redes_para_fortalecer_la_palabra_Una_introduccion_al_Activismo_Digital_de_Lenguas_Indigenas_en_America_Latina (Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20250329213932/https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323226483_Apropiarse_de_las_redes_para_fortalecer_la_palabra_Una_introduccion_al_Activismo_Digital_de_Lenguas_Indigenas_en_America_Latina)

Melucci, A. (2001). Vivencia y convivencia: Teoría social para una era de la información. [Living and Living Together: Social Theory for an Information Age]. Trotta.

Mexican Centre for Environmental Law. (2024). Premio Goldman, resultado del trabajo colectivo comunitario en defensa del territorio y el ambiente sano en la región de los Chenes, Campeche. [Goldman Prize, the result of collective community work in defence of territory and a healthy environment in the Chenes region of Campeche.]. https://cemda.org.mx/premio-goldman-resultado-del-trabajo-colectivo-comunitario-en-defensa-del-territorio-y-el-ambiente-sano-en-la-region-de-los-chenes-campeche/ (Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20250421135329/https://cemda.org.mx/premio-goldman-resultado-del-trabajo-colectivo-comunitario-en-defensa-del-territorio-y-el-ambiente-sano-en-la-region-de-los-chenes-campeche/)

Millaleo, S., & Velasco, P. (2013). Activismo digital en Chile. [Digital activism in Chile]. Fundación Democracia y Desarrollo. https://www.fdd.cl/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/activismo-digital-en-Chile.pdf (Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20250328192942/https://www.fdd.cl/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/activismo-digital-en-Chile.pdf)

Monasterios, G. (2003). Usos de internet por organizaciones indígenas (OI) de Abya Yala: Para una alternativa en políticas comunicacionales. [Uses of the internet by Indigenous organisations (IOs) in Abya Yala: for an alternative in communication policies]. Revista Comunicación, 122, 60-69. https://mapuche.info/wps_pdf/monasterios031100.pdf (Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20240702170744/http://www.mapuche.info/wps_pdf/monasterios031100.pdf)

Múuch Xíinbal. (2024). Asamblea de Defensores del Territorio Maya. [Assembly of Defenders of the Mayan Territory]. https://asambleamaya.wixsite.com/muuchxiinbal (Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20250616130012/https://asambleamaya.wixsite.com/muuchxiinbal)

Pacheco-Campos, J. (2022). Instagram y el activismo digital quechua en Chile. [Instagram and Quechua digital activism in Chile]. In Aguaded, I. (Eds.), Redes sociales y ciudadanía. Cibercultuas para el aprendizaje [Social networks and citizenship. Cybercultures for learning] (pp. 97-102). Grupo Comunicar. https://www.grupocomunicar.com/pdf/redes-sociales-y-ciudadania-2022.pdf (Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20240225022529/https://www.grupocomunicar.com/pdf/redes-sociales-y-ciudadania-2022.pdf)

Red de Resistencia y Rebeldía Jo´. (2024). Sitio informativo de la RRRJo'. [RRRJo' information site]. https://redderesistenciayrebeldiajo.wordpress.com (Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20230423041208/https://redderesistenciayrebeldiajo.wordpress.com/)

Requena Santos, F. (1989). El concepto de red social. [The concept of social networking]. Reis, 48(1), 137-152. https://doi.org/10.2307/40183465

Statista. (2024). Social networks with the highest percentage of users in Mexico in 2023. https://es.statista.com/estadisticas/1035031/mexico-porcentaje-de-usuarios-por-red-social/#:~:text=Facebook%20sigue%20siendo%20la%20red,con%20m%c3%a1s%20de%20un%2080%25 (Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20250709124230/https://es.statista.com/estadisticas/1035031/mexico-porcentaje-de-usuarios-por-red-social/#:~:text=Facebook%20sigue%20siendo%20la%20red,con%20m%c3%a1s%20de%20un%2080%25)

United Nations. (2018). Informe de la Relatora Especial sobre los derechos de los pueblos indígenas sobre su visita a México. [Report of the Special Rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples on her visit to Mexico]. (Technical report). United Nations. https://hchr.org.mx/wp/wp-content/themes/hchr/images/doc_pub/2018-mexico-a-hrc-39-17-add2-sp.pdf (Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20250625022625/https://hchr.org.mx/wp/wp-content/themes/hchr/images/doc_pub/2018-mexico-a-hrc-39-17-add2-sp.pdf)

Vandana, S. (2004). Las guerras del agua: Contaminación, privatización y negocio [Water Wars: Pollution, Privatisation and Business]. Icaria Editorial.

Copyright

Authors contributing to Information Research agree to publish their articles under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which gives third parties the right to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format. It also gives third parties the right to remix, transform and build upon the material for any purpose, except commercial, on the condition that clear acknowledgment is given to the author(s) of the work, that a link to the license is provided and that it is made clear if changes have been made to the work. This must be done in a reasonable manner, and must not imply that the licensor endorses the use of the work by third parties. The author(s) retain copyright to the work. You can also read more at: https://publicera.kb.se/ir/openaccess